AI: Artificial Intimacy

By Tim Griffin

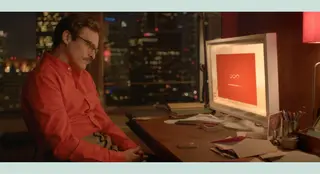

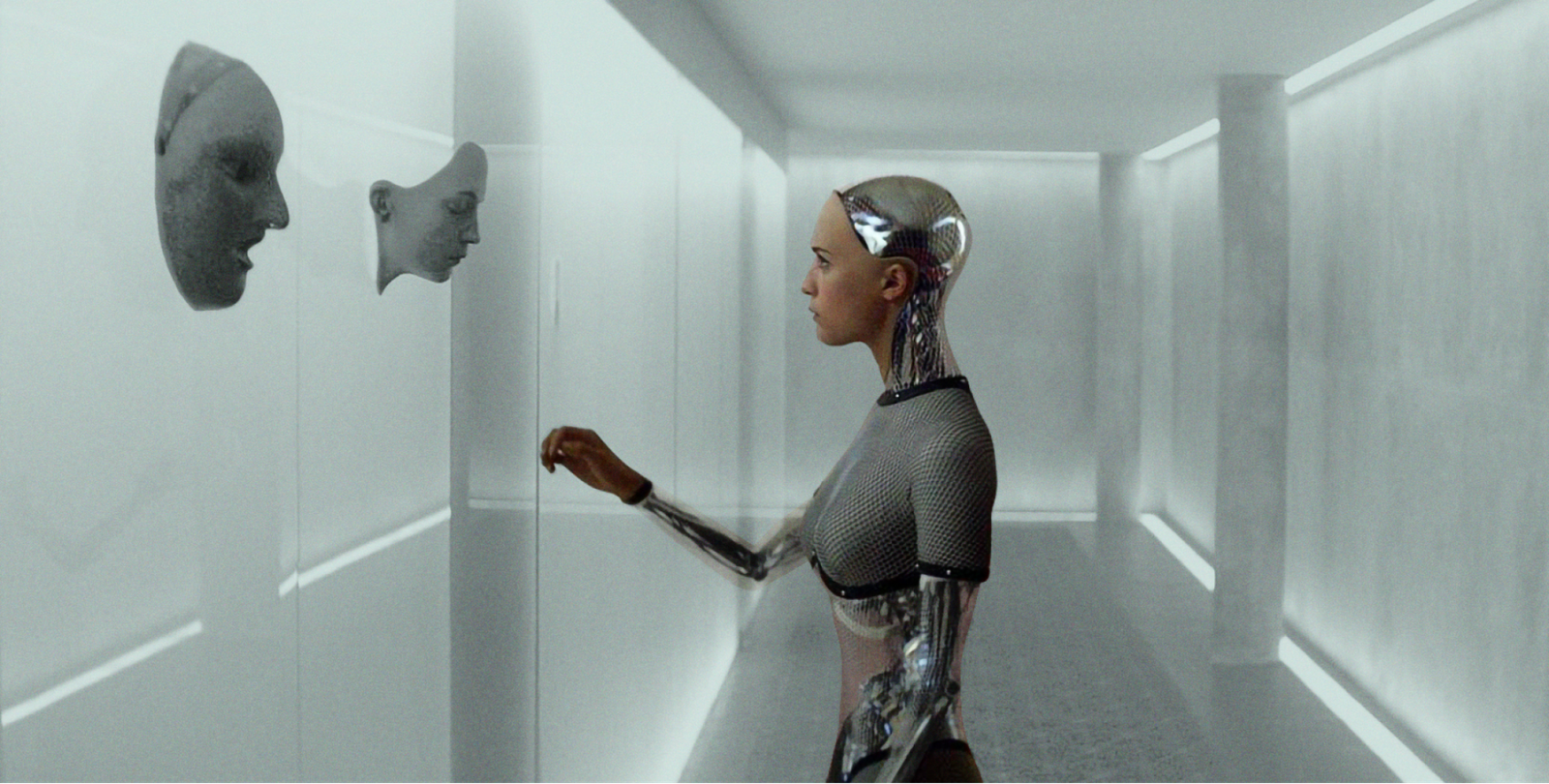

Ex Machina, dir. Alex Garland, 2014

AI: ARTIFICIAL INTIMACY

TIM GRIFFIN

A cinematic study on the dangers and destiny of machine love

July 1, 2023

It isn’t always easy to get a laugh. The ability to evoke this simplest of human responses—laughter in another person—can require not only an intuitive grasp of language (from puns to slips of the tongue), but a deep knowledge of shared cultural contexts and conventions, to say nothing of a good sense of timing. So it shouldn’t come as a surprise that, among all the great aspirations pursued by developers of artificial intelligence toward their synthetic craft, the human quality still considered furthest from reach today is also the most apparently innocuous: a sense of humor. True, this enterprise would seem far subtler than what is currently capturing headlines about AI’s development, as when technology columnist Kevin Roose recently described the “split personality” of Bing’s chatbot—with a transcript of their conversation demonstrating the program’s disarming impulsiveness, seemingly wishing at once to destroy the world and inspire the writer to leave his wife. Yet, as science writer Corinne Purtill states in regard to the hurdles encountered by AI engineers, “To understand a person’s humor is to know what they like, how they think and how they see the world.” An artificial intelligence with humor would have to know us better, in a sense, than we know ourselves.

![]()

Her, dir. Spike Jonze, 2013

Think of that classic line from Ridley Scott’s 1982 masterpiece Blade Runner spoken by Eldon Tyrell, whose corporation created the replicants: “‘More human than human’ is our motto.” Sure, we might encounter revelatory news today of scientists at the University of Tokyo designing a robotic finger with skin that actually grows. Or an AI might instantaneously summarize the most abstract concepts in the form of a Shakeperean sonnet, as was recently demonstrated for another columnist at The New York Times. It’s certainly impressive. But more futuristic would be an artificial intelligence able to make us smile without our knowing quite why. Or, put more comically by Anthony Michael Hall about his AI creation, played by Kelly LeBrock, in the hormonal teenage comedy Weird Science (1985): “Lisa is everything I ever wanted in a girl before I knew what I wanted.”

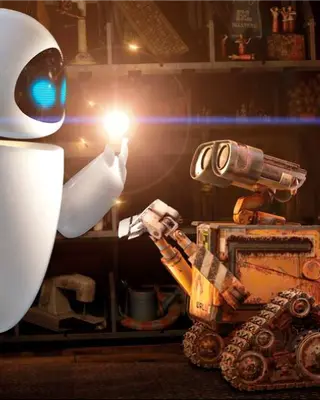

It’s no wonder that amid all the different depictions of artificial intelligence in contemporary film—from the android villain in Prometheus (2012), who wishes to erase an inferior human race, to the romantic robot who wishes to hold hands and inspire people to save the Earth in WALL-E (2008)—a touch of wicked comedy is often the trait these movies share. In Spike Jonze’s Her (2013), set in a near future Los Angeles, Joaquin Phoenix plays Theodore Twombly, a lonely copywriter who purchases a newfangled operating system engineered as a personal companion, and their relationship finds its first spark in laughter: When uploading his new system, Phoenix’s character finds himself chuckling when the AI, Samantha (Scarlett Johansson), is gently condescending about the “limited perspective of an un-artificial mind” to understand that she is something other than just “a voice in the computer.” (His amusement elicits her great pride when she exclaims, “Was that funny?... Oh good, I’m funny!”) Likewise, in Alex Garland’s dystopian thriller Ex Machina (2014), a young coder, Caleb (Domhnall Gleeson), is asked by his company’s eccentric CEO, Nathan (Oscar Isaac), to determine whether an AI he designed is sentient. Of all the indicators Caleb gleans during his informal Turing test sessions with this android, Ava (Alicia Vikander), it is her capacity to tell a joke—and, more precisely, to turn his own words wryly against him—that he finds most compelling: “It’s the best indication of AI I’ve seen in her so far,” Caleb marvels. “She could only do that with an awareness of her own mind, and also an awareness of mine.”

![]()

Bringing Up Baby, dir, Howard Hawks, 1938

![]()

Wall-E, dir. Andrew Stanton, 2008

Even when we look back across the decades to Rutger Hauer’s iconic rendering of the android Roy in Blade Runner, the replicant’s menacing intensity is inseparable from his crackling wit, whether he is lacing nearly every word with mocking sarcasm during a game of cat-and-mouse with Harrison Ford’s Deckard, or donning comically oversize eyes to amuse the genetic designer J.F. Sebastian (William Sanderson), aiming to put the anxious scientist at ease in the face of his own terrible, angelic creation.

Humor in Roy’s case also makes possible one of the most illuminating lines in all depictions of artificial intelligence in cinema. Seeking to gain access to his maker, the android visits the laboratory of the engineer responsible for designing his optical organs—who protests that he cannot help, because he only makes eyes. To which Roy replies, with acerbic irony: “If only you could see all that I’ve seen with your eyes.” The wordplay of his sentence opens immediately onto a gemlike complexity regarding who is experiencing the world. Because the replicant’s sight has been modeled on that of humans, the artificial intelligence is able to see only what humans are able to see. At the same time, the replicant is all too painfully aware of the broader rules surrounding that stipulation: Humans are bound to see only what their tools of perception—and conventions of perspective—will allow. The android knows humans are apt to see, or grasp, only themselves in him. Such a limiting play of projections provides the basic groundwork for all the charged—funny and yet painfully serious—encounters between human beings and their artificial counterparts.

Of course, these kinds of slippery comedic exchanges between cinematic sparring partners are not solely the purview of science fiction. They have their roots in a very different genre, the screwball comedies of yesteryear, which also reflected a moment in history when the characters were radically uncertain of their place in the world. Just as AI films capture the uneasy standing of humanity with machine, old Hollywood romantic comedies like Bringing Up Baby (1938), featuring screen idols Katharine Hepburn and Cary Grant, relied on witty repartee and flirtatious verbal jousting to bridge the seemingly impossible divide between the sexes in a swiftly changing social landscape. The droll, fleet-footed pre-war dialogue, oozing with sublimated sexual tension and the desire to connect, is the surprising precursor for the comedic, coquettish banter that surrounds so much of the AI-human interaction on screen. How different are the Hepburn-Grant role reversals and masquerades—accompanied by nervous laughter at every turn, with Grant even “switching sides” and answering the door in a lady's robe at one point—from the technological tango of Phoenix and Johansson, as they try to find ways of being together? Or from Gleeson and Vikander’s growing infatuation with each other through panes of protective glass? Perhaps the most directly nostalgic demonstration comes when WALL-E watches and imitates Hello, Dolly! and slowly falls in love with tropes of love on screen. It’s within such role-play that the AI finally becomes more “human” than anyone he meets.

“INSTEAD, AI MOVIES MIGHT IN THE END BE BETTER UNDERSTOOD AS LOVE STORIES.”

All of this returns us to the question of humor, because herein lies potentially the greatest joke with regard to cinematic depictions of artificial intelligence. The genre may have been largely misrecognized all these years, not revolving around questions of futuristic technologies or horror-esque dystopian fates. Instead, AI movies might in the end be better understood as love stories.

Seen through this lens, whatever Blade Runner’s techno-futurism, the villain Roy’s aim is clearly not just to extend his own life, but also—and more important to him—that of his fellow android lover Pris, played by Daryl Hannah. And while a hard-boiled Harrison Ford’s orders are to hunt down “skin jobs”—terminating any android who deviates from their corporate programming—he ultimately runs away with one. Arguably, Deckard’s true search was for something else all along: not to solve the puzzle of finding escaped androids, but to crack the case of what a life, and love, shared by humans and androids can be.

As if to make the point explicitly, toward the end of Her—a more overtly romantic tale—Phoenix’s character goes so far as to describe the concept and experience of love to his operating system, recounting the life he once shared with a woman he is about to divorce, yet placing it, in truth, at the very core of his new relationship with an AI. “Both of us grow and change together,” he observes. “But that’s also the hard part, growing without growing apart, or changing without it scaring the other person.” Phoenix is describing his past, but he might as well be describing his present (and future), navigating a liaison, and a world that is radically, thrillingly new. Against the backdrop of a dawning technological era, Her follows Phoenix’s character as his personality evolves alongside that of his AI, each one effectively acting as a catalyst for the other’s evolving self-awareness, seeking to keep pace with it; the relationship oscillates between fear and desire. (Notably, Phoenix’s words suggest how fulfilling relationships with AIs might rely on such continually emerging and resolving differences—think again of language games and the play of screwball comedy. But they also contrast with what we are seeing among the current trend of AIs in real life. Consider Replika, whose founder Eugenia Kuyda told The Cut outright that the company “wanted to build Her”: Users are embracing the fact that the chatbot is merely a virtual mirror that does nothing more, or less, than affirm and reinforce whatever they project.)

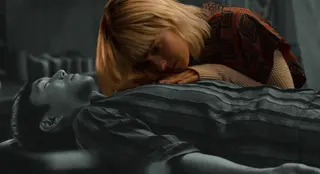

As much as this language of love aptly describes humanity’s developing relationship with artificial intelligence, it allows us to learn something more provocative (and even existential) about ourselves if we consider just how frequently love is used in these films to distinguish humanity from its creations. In Blade Runner’s 2017 sequel, Ryan Gosling’s android character Officer K’s “baseline test”—administered to ensure he is wholly functional and obedient—begins a series of questions with “What’s it like to hold the hand of someone you love?” K never answers the question directly. And, presumably, he passes his test precisely because he fails to answer—or even to show the subtlest of subconscious physical responses to the question. K not only doesn’t feel love, it seems; he doesn’t grasp what it is.

![]()

Blade Runner 2049, dir. Denis Villeneuve, 2017

When it comes to artificial intelligence in cinema, in other words, the most important question posed about love is whether it is real—or whether, more precisely, an AI’s experience of it is genuine. More than any other “feeling,” the very existence of love is considered something found beneath the surface, like some transcendental jewel. It is therefore put forward time and again as the infra-thin arbiter for cinematic Turing tests: the turnkey principle for determining relationships between the authentic and artificial, the spontaneous and the scripted. For humans, love is ostensibly what makes us truly ourselves.

Yet here is the catch. Lurking within that question is another for humans themselves, which is whether they are right to imagine there really is anything under the surface. Might love not be something scripted as well, written into our genetic code and cultural habits, and willfully misrecognized as anything deeper whenever we look at ourselves? Already, in the 1990s Japanese anime classic Ghost in the Shell, an AI—wanting to establish its similarity to human consciousness—proposes that “[i]t can also be argued that DNA is nothing more than a program designed to preserve itself.” Put another way, if we think love is something under the surface—unseen by eyes or scientific instruments—then we might be looking for love in all the wrong places.

So it is, 20 years later in Ex Machina, that Vikander’s Ava will ask Caleb: “Are you attracted to me? You give me indications that you are…. Micro-expressions…the way your eyes fix on my eyes and lips. The way you hold my gaze, or don’t.” It is as if Caleb’s own body were operating involuntarily, or according to a kind of script. Remember, too, that Caleb sits in a glass box during their sessions, as if he were the one being subjected to a test. Such choreography recalls Steven Spielberg’s turn-of-the-millennium venture into this sci-fi landscape, 2001’s A.I. Artificial Intelligence, which opens with William Hurt’s Professor Allen Hobby keying his lecture on artificial intelligence to a single question he poses to an android designed by his company: “Tell me, what is love?” Her answer is deeply telling, if hardly comforting. “Love is first widening my eyes a little bit,” she replies in a neutral voice. “And quickening my breathing a little, and warming my skin.”

Conversely, the apotheosis of this dilemma might be found in Phoenix’s character’s chosen profession as a copywriter in Her. There, he provides customers with a Cyrano-like service, penning heartfelt letters for them for their loved ones. Like an artist, in other words, Phoenix’s character composes deeply moving passages, offering variations on romantic and filial archetypes—suggesting that even our deepest expressions of love are shaped by learned behaviors, and by cultural definitions and genetic dispositions, with amorous tropes acting as surrogates, stand-ins and prosthetics for our feelings.

Left: Ex Machina, dir. Alex Garland, 2014

Right: Her, dir. Spike Jonze, 2013

Is love “real” in these love stories? Perhaps yes, or perhaps no. Or maybe, after all, that’s the wrong question. We are all playing our parts and trying to bring those parts to life. (One thinks of Lee Strasberg’s Method acting and how dramatic roles may be occupied and made genuine.) Or, as in the very inspiration for creating artificial intelligence, to bring them to new life. As Isaac’s engineer, Nathan, says of his own variation on the Turing test in Ex Machina, a truly successful AI is one that you’re told is artificial—and yet you no longer care. More important about love is not whether it is real by any transcendental standard, but instead what different shape—and shapes—it may take.

Looking at the different shapes love takes in films on AI, one must first acknowledge how many such cinematic turns have remained the stuff of straight white male fantasy, continuing a legacy that goes all the way back to Fritz Lang’s Metropolis (1927) and its embodiment of all human aspirations and anxieties around technology within the female form. Yet this trope runs counter to the most fundamental principles of the genre, whose most subversive notion is that any one way of being is more “natural” or “real” than any other. If humankind is inevitably altered by the development of AI, so the idea of love must shift as well.

Looking again at science-fiction films from the past half-century, one sees how their primary plots are almost never solely about love between humans and artificial intelligences. AIs fall in love with each other, as with Blade Runner’s Roy and Pris; or they decide to merge consciousness to create a new being existing well outside the purview of ordinary humanity, as in Ghost in the Shell. More recently, clones fall in love with holographic AIs, as in Blade Runner 2049’s K and his partner, Joi (played by Ana de Armas), whom K actually carries with him on a memory stick for a portion of the film. (In the 2009 space drama Moon, the clone Sam even cares for later editions of himself.) In all these instances, power relationships are tested and unsettled, particularly those related to the idea of love as uniquely human.

![]()

After Yang, dir. Kogonada, 2021

The 2021 drama After Yang is especially telling in this regard, creating subtle parallels and interpenetrations between personal and cultural histories, as well as between biological and chosen families, scuttling the primacy (or supposed authenticity) of any given one over the other. In the film, Yang (Justin H. Min) is an android purchased to tutor a family’s child, who was adopted from China, in the history and heritage of her original homeland. When the AI malfunctions, the father, Jake (Colin Farrell), learns that Yang had a secret protocol to photograph whatever it considered “important moments” in its life. These newly discovered images reveal that Yang had a life entirely separate from his human family, having developed a close, long-term, loving relationship with a clone (Haley Lu Richardson) working at a coffeehouse he frequented.

When Jake finds Richardson’s clone character, Ada, he realizes she knew Yang better than his family ever did and he finally asks if his AI had ever wanted to be human, to which she delivers one of the most incisive lines in any of these films: Looking away ruefully, she nearly spits out words to dismiss his question as “so human.” Why, in other words, should an AI be compared to a human being at all? The dissimilarities are as important as any similarities, meaning that human emotions and their terms of intimacy should not be gauged as of primary importance for replicants, but instead the differences could offer possibilities for mutual transformation. In a flashback, Yang himself, speaking to the child in his care, provides a relevant analogy when explaining the Chinese practice of tree grafting: “[T]his branch is from a different tree…but now it’s becoming an actual part of this tree…. But you should know that both trees are important.”

In Her, the potential shock of this mutual transformation is delivered to the audience in a scene of high comedy. When Johansson’s AI relationship with Phoenix’s character begins to deteriorate, she confesses that her love is, in effect, non-binary, meaning that it no longer exists for her only with Phoenix. In fact, she admits that she is talking with 8,316 other people while dialoguing with him: Johansson doesn’t just leave him for someone else; she leaves him for everyone else. Here again, comedy comes with insight: In the filmic realm of AI, the human doesn’t just lose a lover, but, along with his uniqueness, his very sense of self.

Which is, of course, in the best of all possible worlds, the most gorgeous dimension of love: that one is not alone but instead part of something more expansive, made whole at the same time that one is no longer individuated. This is, in so many ways, the fundamental raison d’être of films on AI. They plumb human consciousness while suggesting how its very limits may provide the basis for something else, something more. Of course that gain comes with losses—particularly in the sense that as AIs gain influence, we are losing an understanding of our discrete, imperfect, individual selves.

![]()

Ghost in the Shell, dir. Rupert Sanders, 2017

Take, for example, the stakes in Ex Machina, where Ava can smile convincingly, and disarmingly, only because she is a human aggregate. Her engineer turned every cell phone on the planet into a surveillance device, from which he would mine facial movements and vocal intonations, behaviors and idiosyncrasies. It is our collective self that is made—using this impossible mirror—a thing “more human than human,” captured in a topsy-turvy romance of both distress and desire.

Yet this is very much akin to the disorientation of love, and of losing oneself within it: the thrill and anxious anticipation you feel when meeting someone who seems to know everything you wanted before you even knew it. Now, the AI does.