Blood on the Tracks

By Robert Bound

Nosferatu, dir. Robert Eggers, 2024

Blood on the Tracks

Robert bound

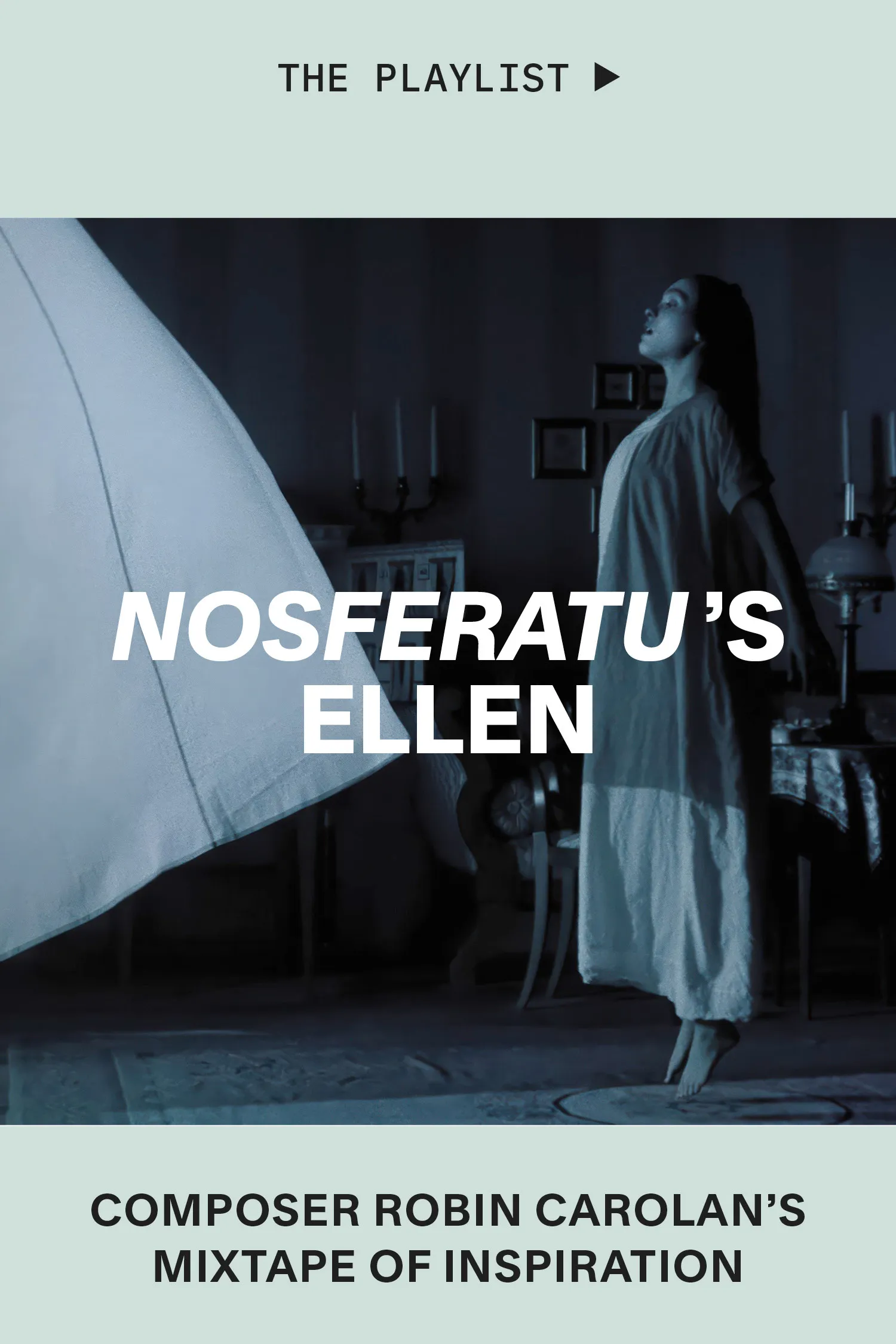

Nosferatu composer Robin Carolan reflects on using playlists, Dictaphones, music boxes and a vast orchestration to get inside Ellen’s (Lily-Rose Depp) vampire obsession

February 28, 2025

Robin Carolan

The score for Robert Eggers’s Nosferatu is a cavalcade of squealing horns, screeching strings, swirling bass and swooning choruses befitting a film of maximalist horrors. You’ll also hear elements of fairy tale, the pastoral and the romantic. Such nuanced texture is the work of British-Irish musician and composer Robin Carolan, whose vital soundtrack breaks with the camp trappings typical of the genre and layers beautiful, warped emotionality into this gothic reckoning with the undead.

Nosferatu tells the tale of Ellen (Lily-Rose Depp), a young wife haunted by a deathly obsession with Count Orlok (Bill Skarsgård), an ancient, voracious vampire who visits her dreams and sows mayhem throughout Ellen’s family and across the wider world. A re-“vamp” of F.W. Murnau’s 1922 silent horror film—itself based on Bram Stoker’s novel Dracula—the film is a breathless succession of haunted forests, ominous castles, waking nightmares and blood-gulping vampires. Carolan’s score balances the jump-scare necessities of a horror soundtrack with the sadder and subtler strands sewn into Eggers’s pitch-black epic, specifically Ellen’s punishment at the hands of a series of scared and angry men. There is plea, petition and finally resolution in the way that Carolan’s music tells Ellen’s story. To achieve this, Carolan enlisted an expansive orchestra—helmed by Daniel Pioro, a young British classical musician—incorporating both contemporary instrumentation as well as ancient horns, pipes and percussion sounds to lend credibility to a film set in the 1800s.

A polymathic artist, Carolan founded Tri Angle, a much-revered record label based in London and New York whose roster featured influential acts such as Evian Christ and Clams Casino; Carolan has also collaborated with Björk and Lyra Pramuk. He folded the label after a decade and “kind of checked-out” from music he says—until receiving a call from his friend Eggers to work on The Northman (2022), about a spiritually troubled Viking embarking on a vengeful blood-fest, for which the composer delivered an inspired Nordic-folk soundscape. With their latest collaboration for Nosferatu, Carolan proves he is very much checked in right now.

From left: Lily-Rose Depp and Emma Corrin in Nosferatu; Lily-Rose Depp as Ellen

How did you and Robert Eggers talk about the music for Nosferatu? Are you sitting at a piano playing chords or are you discussing ideas of the gothic or the romantic in words?

Rob and I are mates and were friends before we started working together, so we’ve always had a pretty good dialogue with each other, and we often talk about film or music. I have a pretty clear idea as to what he wants and what he doesn’t want, and it helps that Rob and I have very similar sensibilities. To begin with we just start building up playlists of music, things that we think will be inspiring or interesting or there’s something to really excavate and go further with. I start to whittle them down into what I think the sound of the film could be. I think because we’re mates we’ll also challenge each other, which really helps. For Nosferatu, Rob wanted everything to be big and grand, and he pushed me to take it there.

And then the subtleties come in?

Yes, we talked a lot about the emotional aspect of the story and particularly Lily’s character, Ellen. I was most obsessed with Ellen’s character in terms of capturing what she’s going through and what her life is like in the music. She’s very tragic and misunderstood, and I was excited to write music for someone like that. You could say Amleth in The Northman is similar, but because that film is so macho, because it’s a fighting culture, it was harder to put that sensitivity into the score. But with Nosferatu, I could take it further and really lean into those emotions. I really loved that aspect of it.

So you sketch out a sound universe for each character?

For sure—and this goes back to making the playlists, which I do as I read the screenplay. I made playlists for each separate character, imagining their backstory and creating their sound world. It was very clear that Orlok’s playlist was going to be very different to Ellen’s playlist, which would be quite different to Hutter’s playlist. Although there is a bit of bleed-through.

Scenes from Nosferatu

“I wanted this innocent music-box idea to also be corrupted.”

Well, there’s certainly plenty of gory bleed-through in this particular film. How do you match music to the horror elements?

It was clear that this was going to be a score of two halves. On the one hand, it has to function as a horror score, so you have to make sure that the tension and the jumps are there. The score had to feel like a spiral that you’re sliding into or being dragged into, and it had to contain enough dread. On the other hand, Ellen is a misunderstood, haunted figure who’s gone through life feeling a lot of sadness, melancholy and confusion about where she is in the world, and so it was important to lean into that stuff and build up the tragedy of her character. There are some weird romantic themes going on in her part of the score, but it’s really more about her obsession.

The score is tracing the complexities of Ellen’s state of mind, then?

Yes, that’s the thing. In the Victorian era in which Nosferatu is set, Ellen would have just been referred to as crazy. When she’s having a fit, the male characters just strap a corset on her to try and calm her down. She’s constantly going through these different emotions and states. But I think what’s really clear from beginning to end is that she becomes more confident in understanding herself, even if that leads down a path of self-destruction or sacrifice. But she does also save the day, so when I was writing the music for the end of the film, I wanted it to have a semi-religious, triumphant feel to it. Ellen has taken control of her destiny and she does what no one else can do.

How did this bear itself out on those playlists and musical mood boards? It sounds like you could have included everything from Tchaikovsky to Motörhead, so what was the spectrum?

Rob and I are always talking about [Krzysztof] Penderecki, [György] Ligeti and [Béla] Bartók, those great 20th-century classical and experimental guys. Then we listened to a lot of Wagner and Beethoven because they were of the period the film’s set in. The 1800s were typified by classical music with a Romanticism about it, and we really wanted to capture that in the score. Then on the more experimental and contemporary side of things, there was a lot of Coil [an experimental British band], which would get me into a certain mood when I was writing for Orlok. I’ve always been massively inspired by Autechre [a British electronic duo] and go for long walks here in the Essex countryside listening to their stuff. There’s a lot of space in their music to think about melodies. When I first start to think of themes, I’ll often listen to drone music. It’s a good base and puts you in a certain mood, but there’s no melody to disrupt how you might want to write.

So you’re out on a hike, getting into the mood…. How do you take notes?

I always carry a Dictaphone with me, and I just hum into it or describe how it could connect up with another idea. I’ll hum something, and then I’ll say, “Reference this for scene blah, blah, blah.” Then, when I go into the writing room to start the project properly, I’ve usually got a lot of ideas. I picked up the humming thing from Björk. She has a habit, when you’re out and about with her, of suddenly just humming into her iPhone or a Dictaphone. She’s just getting ideas, putting them down and then taking those ideas into the studio. And I thought, Wow, that works and it’s so simple! It’s really a great way to start things off.

Nosferatu opens with a twinkly music-box melody that seems to speak to childhood innocence as well as spookiness. Were you using it both ways?

That first scene is about innocence being corrupted. When I watched some of the early footage of Ellen sleepwalking, her house seems like a doll’s house, and to play her, Lily was digitally de-aged to make her look like a young teenager. So yes: The music box, children, china dolls, all that shit came into it. I wanted this innocent music-box idea to also be corrupted, and for the very last scene of the film, I wanted the score to mirror that. I like the idea of it all coming full circle so that, musically, it mirrors Ellen’s story. Rob and I were both concerned that it was maybe a slightly clichéd thing to do, because music-box stuff does turn up in horror films as a sort of “creepy kid” thing. But ultimately this is a gothic fairy tale, and if you can’t get away with using a music box for 30 seconds, then what can you do? It doesn’t take long for the music to shift and become absolutely punishing after that. So yeah, it was nice to have a brief moment of Disney.

Some very dark Disney. Elsewhere, your score is a very big production with sweeping orchestration. But this isn’t your usual toolbox as a musician, so how did you keep tabs on the scale of it?

It really was a big production and this was only the second score I’d written. The Northman was terrifying to be in charge of because it was my first and I was a bit, “What the fuck am I doing?!” That was a real baptism-of-fire learning process. I’m not a conservatoire-trained musician, but I found a way to write for classical instruments and I found a way to make this kind of music. You really have to surround yourself with people who come from that background and who can be sympathetic as to where I’m coming from and also excited to be a part of the film we’re creating. When it came to some of the more experimental ideas I had [for Nosferatu], I’d sit down with [violinist and composer] Daniel Pioro, who was first chair, and explain my weird ideas, and he would be really excited and would communicate it to the players when it came to recording. Being surrounded by people like that was super important.

The Northman, dir. Robert Eggers, 2022

It sounds like there was a real exchange of information and expertise?

Well, Daniel was in the classical world anyway, and I don’t think there was much I could teach him, really—but I think he enjoyed the fact that I was approaching it in a slightly left-field way. Daniel’s an incredible musician, but he was quite excited about this. He’s done stuff with [Radiohead guitarist and film composer] Jonny Greenwood, and so I think he wants to challenge himself and challenge other people.

When did you start hearing your work in relation to real scenes from the film?

Rob and I probably work a bit differently to other directors and composers in the sense that as soon as he starts postproduction and starts working with Lou [Louise Ford], the editor, then I start too. Rob will write a list of 10 or 12 scenes that are really important and for which he’d like to have demos within a couple of weeks. I start seeing some rough footage and then I don’t really finish until he finishes, so I’m constantly watching the movie get built up.

There are moments in the film when the music seems to lead the action. We know that music is cut to fit a scene, but conversely, are scenes elongated in the edit to make the most of the music?

It’s a bit of both. The last eight minutes of Nosferatu are effectively just daybreak. I wrote that music quite early on in the process, and aside from one note, it didn’t really change. I think Rob just really loved the music and wanted to make sure the film wasn’t edited in a way that would mean my having to rework it. In that particular long, final scene, there are a lot of shifts of instrumentation. It’s a bit of a tightrope, and if it were heavily edited, the music would just unravel. So that felt like an occasion when the music led the scene. Of course, there are plenty of examples where an edit in the action means I’m changing and adapting the score, too. It’s not always easy, but it’s part of the job.