Music for Grief

By Robert Bound

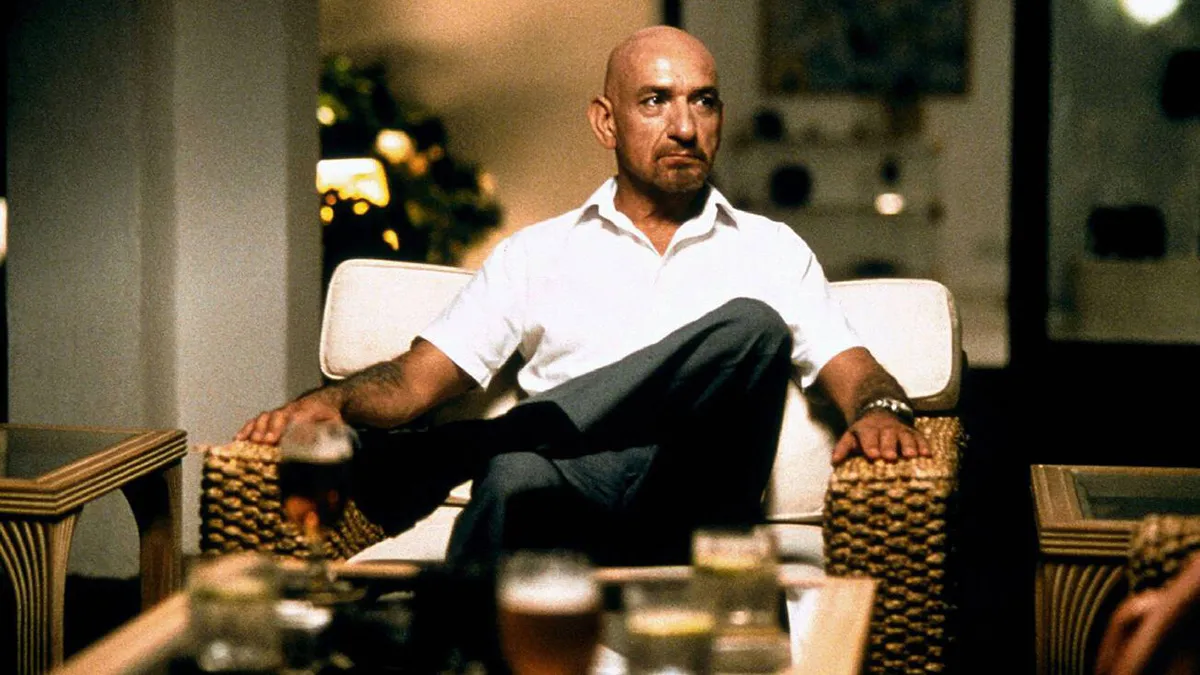

Handling the Undead, dir. Thea Hvistendahl, 2024

Music for Grief

Composer Peter Raeburn on scoring the thoughtful Norwegian chiller Handling the Undead

By Robert Bound

November 05, 2024

Los Angeles–based composer, producer and songwriter Peter Raeburn has worked across film, television and, as founder of Soundtree Music, commercials, brands and charities. He scored small-town mystery The Dry (2020) with Eric Bana and internet-identity drama Nancy (2018), co-starring Andrea Riseborough and Steve Buscemi. Raeburn's partnership with fellow Brit Jonathan Glazer as music producer, supervisor and arranger spans the director’s dark cinematic feats Under the Skin, Sexy Beast and Birth, and he also worked closely on Lars von Trier’s psychological fable Breaking the Waves. Clearly, Raeburn is no stranger to the strange. His latest output, for Norwegian director Thea Hvistendahl’s thoughtful zombie film, Handling the Undead, starring Renate Reinsve and Anders Danielsen Lie as grief-stricken Oslo residents revisited by deceased loved ones, is a haunting, sensitive and memorable score that won the World Cinema Dramatic Special Jury Award for Original Music at this year’s Sundance Film Festival and is in contention for a Grammy. Raeburn spoke to Galerie from his L.A. studio about love and death, composing “non-music” and channeling his own grief into sound.

LISTEN TO PETER RAEBURN'S SOUNDS OF LOVE AND LOSS

What sort of conversations did you and Thea Hvistendahl, Handling the Undead’s director, have about the musical palette of the film?

Before I started to paint with actual music and sounds, the opening conversations were really about understanding the emotional core of the project: a horrifying film about grief and about the worst-case-scenario stuff happening in people’s lives. What drew me to it was trying to share and feel the grief which, instead of being purely unbearable, is really a feeling of love beneath and beyond and all around the grief. So I started to sketch after conversations about what loss means, about what grief means, about what that means to Thea as a director. The palette was kind of the “orchestral afterlife,” or orchestras in the afterlife. A lot of the sounds were made from humans or from humanity, but then channeled into this sense of longing and living on in some parallel way. I was really interested in how the feeling of the ever-living might sound.

You start the film using sacred music in which there’s a lyrical refrain on everlasting life, which can be taken two ways in this case, as it’s also part of the film’s narrative momentum. As a composer, how much do you want to push the viewer with lyrical cues?

It’s very much a collaborative choice. I follow my own instincts, and then I really rely on the director’s instincts to lead the way. The film has a lot of mystery to it. I tried to burrow inside the film and write from inside the performances and inside the themes so that it doesn’t feel that the music is on top of the film. By diving deep and going inside the emotional narrative it becomes not really about telling people what to feel. It’s about feeling it, feeling things all together in real time. There are no manipulative tools in this film. A lot of it is very understated. The music doesn’t have an ego at all.

How “live” was the process of matching the music and the action?

I started sketching ideas while Thea was shooting, and she started playing these sketches on set to her cinematographer, Pål [Ulvik Rokseth], who was amazing. So I think there was a sort of trance feeling: some shared air, some shared feeling through the music on the set. Some of that music made it into the film and some of it didn’t, but it made it into the atmosphere of the film and into the filmmaking process. And then I started getting rushes back with this music on, as if everyone was in this trance. And that’s also how I make music sometimes—I go into a trance, an unthinking place where I’m just searching for the right feeling or the right sensitivity. Wonderfully, Thea refused to use any kind of temp music. She didn’t want anyone to be influenced. Another real testimony to her braveness.

![<I>Under the Skin</I>, dir. Jonathan Glazer, 2013]() Under the Skin, dir. Jonathan Glazer, 2013

Under the Skin, dir. Jonathan Glazer, 2013![<I>Birth</I>, dir. Jonathan Glazer, 2004]() Birth, dir. Jonathan Glazer, 2004

Birth, dir. Jonathan Glazer, 2004![<I>Breaking the Waves</I>, dir. Lars von Trier, 1996]() Breaking the Waves, dir. Lars von Trier, 1996

Breaking the Waves, dir. Lars von Trier, 1996![<I>Sexy Beast</I>, dir. Jonathan Glazer, 2000]() Sexy Beast, dir. Jonathan Glazer, 2000

Sexy Beast, dir. Jonathan Glazer, 2000![<I>The Dry</I>, dir. Robert Connolly, 2020]() The Dry, dir. Robert Connolly, 2020

The Dry, dir. Robert Connolly, 2020![<I>Nancy</I>, dir. Christina Choe, 2018]() Nancy, dir. Christina Choe, 2018

Nancy, dir. Christina Choe, 2018

“I think writing with your eyes closed is actually really, really important.”

I love that idea of the music, as you composed it, becoming used almost as direction in the actors’ armory. There’s a lot of talk of collaboration on set, but this feels like a genuinely open idea of what the music can do for the images and the images can do for the music and how they both equally affect the other.

I think because the music wasn’t trying to dictate feeling—it was really there to allow it—that’s the distinction. It was like a color or a smell that infused things. The themes in and around this film are really brave and the filmmaking is very beautiful. When I sat with the filmmaker at Sundance for the film’s first foray into the world, I had no idea how it was going to be received, and it played in that cinema so well by asking questions more than giving answers, and posing challenging suggestions, but in a very generous way—in that amazing kind of Nordic way, not feeling like it needs to justify its own cinematic existence.

And there is that spareness to the film—from the performances to the landscape, they’re very Norwegian and sparse and beautiful. Your score is similarly spare. Did it quickly become the obvious tonic for the film?

Sometimes I would write quite a lot of music and then we would decide to strip things back and only use it where it was really needed. This is another thing that happens—sometimes the real sound of the film doesn’t establish itself until later in the process. Music tries to make up for a lot of things that haven’t been done yet, but because I have quite a lot of experience on the sound side of things, I was promising that this or that moment would not need to be filled with music. I was making these atmospheres, sounds that are something in between music, air and sound. I made quite a lot of those for this project, and they really did a lot of work to let the stillness happen. I think that’s the sparseness as well as the fact that the dialog is efficient—there aren’t endless conversations. I mean, I love dialogue and I love words and poetry and scripts, but somehow this photography and the haunting subject matter needed less, and that’s again the braveness that Thea had. It wasn’t even a question.

Are you always referencing the images when you compose for film? Or can you enter the atmosphere of a project and then take yourself away to a darkened room and compose with the memory of the film in your mind?

If we work too closely to the picture all the time, then the music can become a slave to what we’re seeing and not find its way into the fabric of the story. So I like to do both things when I’m writing the bigger pieces. I’m extremely conscious of the amount of time things have to take, that they have to take the right amount of time and that they have to hit at the right moment. But I internalize those quite carefully, they go into my unconscious, so that I know what story I want to tell or where a cue starts and where it wants to end up. And so I think writing with your eyes closed is actually really, really important. Having done that, I then get massively obsessed with synchronization and cuts and dynamics. And then once the writing’s done, I get very focused on exactitude: when it comes to the picture, knowing that things can be changed, but there has to be something there to change and focus on in the first place.

So the music is in danger of being wasted if it’s not being serviced by that precision and syncing with the image and vice versa?

Completely—and it has to be an incredibly well-oiled machine. It really is about servicing and serving a film. I get very obsessed with where music comes in and where it goes out. There’s got to be a reason for these things to happen, in my opinion; otherwise what was it doing there in the first place? Especially in a film like Handling the Undead, where there’s a lot of non-music—there is a fair amount of score, but it’s not wall-to-wall.

And non-music is sound design—suggestions and moods?

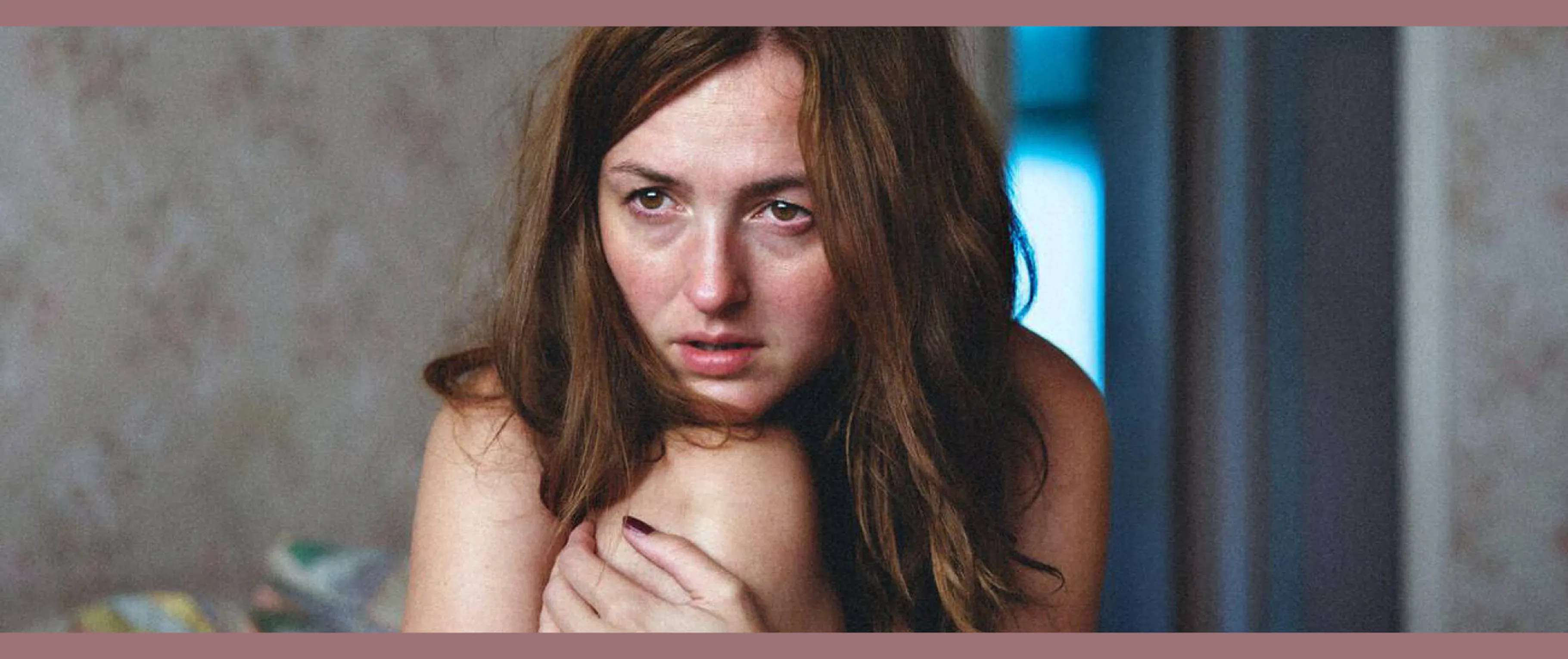

Yes, there’s formal music, definite melodic material, but then there’s more atmospheric stuff which is non-formal music. The music is a kind of emotional microscope, a scan of a character’s inner self, so then it’s all about judging when it should come in and out according to a certain look. Is it on one character or another? Is it brave? Does it kind of waft into the atmosphere? Handling the Undead is quite a quiet film, so it allows for a lot of poetic license and processing of sounds that can just fall into the air, sometimes taking many seconds to do so. And it really comes back down to the performances. Trading on an actor’s performance is the last thing I ever want to do. In this case, I had studied Renate’s performance [Reinsve plays Anna, a grieving mother]. But like every actor I score I have a complete relationship with these nuanced performances—their breaths, blinks, movements—so that it feels like I’ve hardly done anything with the music. That’s the whole point: If you get those things right, the music doesn’t feel like it’s trying hard to exist or not exist.

Going back to your initial conversations with Thea, when discussing themes and ideas for the film and the music, what sort of words and adjectives were you using?

The conversations between Thea and myself led to a feeling and an intention, and I have a job to represent that intention. Getting inside the head or the heart or the spirit of a filmmaker, and of a script, requires a lot of unconscious communication. In this particular film, it was clear that we weren’t making a classic horror movie. There are no jump scares, really. That would obviously have been a different palette, a different kind of sound, and there are brilliant ways of doing that, but that just wasn’t Thea’s mission. This is a story of people who are confronted with out-there scenarios and feelings, and my job was to make that feel—not palpable—but actually a reality. And that’s where music plays a very strange role, and that’s where the music that I wrote doesn’t put the film into a genre. It’s not classic horror, it’s not classic romance, it’s not classic anything. It’s just what we made—and that’s a lovely feeling.

From left: Renate Reinsve, Anders Danielsen Lie and Bente Børsum in Handling the Undead

Is an illustration of that the point when the undead reveal their nature and your music becomes more urgent but also stays complex and unresolved?

Well, we knew that the film needed to have its catharsis, but that had to be timed really carefully. The whole backdrop of this zombie apocalypse is happening in such a mindful way. It’s so not in your face—it’s not breaking news. But there are feelings, and they’re personal. It’s not like the kind of ambient fear that happens in times of war or environmental crisis. It’s these personal apocalypses: Someone’s buried their son and then they find him in bed, but it’s not really her son, but it is really her son, but it’s not really her son. Scenes like that were so extraordinary to score because too much and it’s lost, and too little and it’s not enough. There was a lot of prodding the film and seeing what happens, like a science experiment—seeing what reactions happen.

How did you go about scoring the horror high points of the film, including what we can only describe as “the rabbit scene”?

That was an interesting scene to score because we are mixing emotions of love and horror. Right there you feel the love—whether it’s the historical or the actual love—between a mother and a son, and then how that love, that touch, can suddenly be deadly. There’s another scene involving a couple, set at breakfast, and this line between wanting to feed someone as an act of love, but that person wants to feed on you—there’s a deep concept right there, the vampiric nature of love, and all kinds of possible readings. I also made a sound called “Dead People,” which is made from voices that don’t sound like voices anymore, and it’s right through the score. It has a feeling of everlasting life and yet lifelessness, and it’s these contradictions that the film is interested in. I know as a grieving son that I feel my mother to be both alive and dead, often in the same moment, often in the same day. And these are the contradictions of these existential, philosophical questions. I applaud a film that goes there and asks those questions. And I know people who have seen this film and have found it comforting. Confrontational but comforting, because it isn’t telling them. It’s not a self-help film that’s saying “you should do this.” It’s saying, “We’re in this together.”