Instruments of Change: Matthew Herbert

By Robert Bound

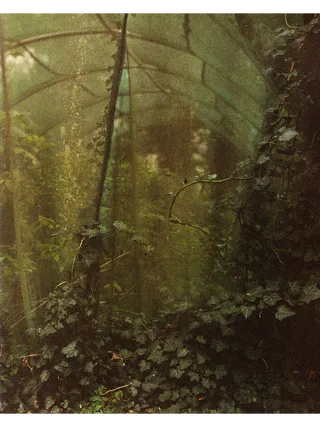

Matthew Herbert at home in Kent, England

Instruments of Change

With tools ranging from the primitive to the high-tech, Matthew Herbert composes film scores of protean invention from his bucolic farm-studio in england

By Robert Bound

May 08, 2024

Photography by Elena Heatherwick

Renowned composer, producer and author Matthew Herbert’s boundary-defying approach has made an indelible mark on everything from house music and electronica to contemporary orchestral work and film soundtracks. His belief in making music that is as elemental as it is experimental has led him to create radically conceptual albums rooted in their very subject matter: One Pig is a record made from the heartbeats and body parts of a farmyard animal from birth to slaughter to supper, and his most recent record, The Horse, traces the evolution of music via the life of one such titular beast—played on instruments fashioned from equine bones.

Herbert’s film and TV work spans more than two decades, but his score for Sebastián Lelio’s 2017 film A Fantastic Woman ignited an enduring collaborative exploration. The Chilean director has just wrapped production on political musical The Wave, for which Herbert enlisted generations of female Chilean songwriters, while previously the duo partnered on Disobedience (2017), Gloria Bell (2018) and The Wonder (2022)—the latter a subtle thriller about faith and reason set in rural mid-19th-century Ireland and starring Florence Pugh. The composer’s delicate, persuasive score is wrought from that deep reading of story and intention that is now a Herbert hallmark.

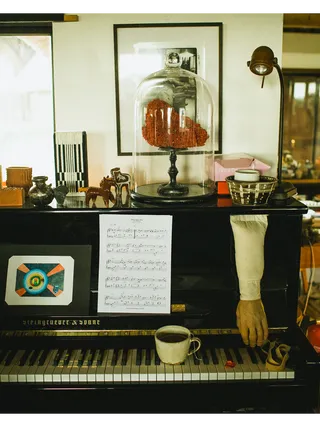

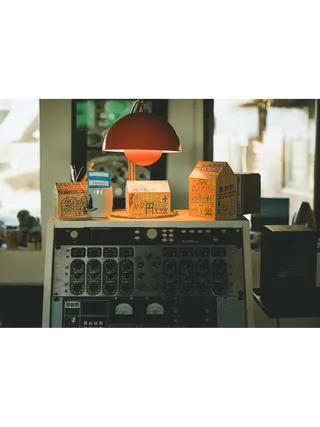

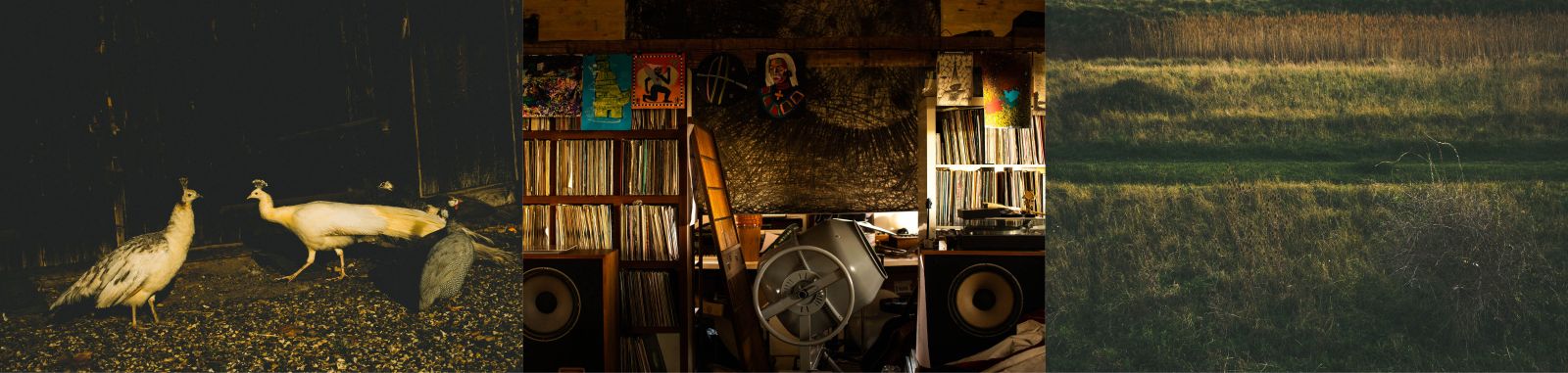

Based in a converted barn adjoining his early-17th-century farmhouse in the marshes of Kent, England, Herbert’s studio is a jam-packed cathedral of inspirations where musical equipment shares space with thousands of LPs, cabinets of ceramics, assorted artworks, a cement mixer and the bones of that horse. On a chilly, sun-drenched winter morning, the sonic inventor elaborated on his approach to work and wonder.

Thanks for welcoming us to your home studio. It’s a beautiful production space, and you’ve got such amazing pieces of kit. What are your main tools of the trade?

The biggest tool for me, particularly as I get older, is the windows. Most recording studios don’t have natural light, they don’t have a view, they try to shut out the world, and there’s lots of soundproofing to create this hermetically sealed bubble. I understand why you might want to do that when recording an orchestral film score or something like that, but when you’re trying to tell stories and to engage with the world, personally I need to be connected to it somehow. The main part of the farm dates from 1600. I share the space with a variety of animals, lots of voles live in the roof. You might hear them scurrying about, and sometimes squirrels get in and birds and swallows come in and fly around the studio in the summer.

Flora and fauna aside, there’s some serious audio hardware arrayed around us.

My dad was a sound engineer at the BBC and good quality audio is really important to me, so I’ve spent a lot of money over the years buying and trying different things. I’ve sold a lot of it to come to the bare minimum. The majority of my work these days is computer-based, even my own work, but particularly film and TV work. There’s no time to run it through analog equipment at all. You need to create hundreds of pieces of music for a TV series and you then have to record stems, where you separate all the components into the different parts—so you might have a drum track, an orchestral track, a vocal track, an effects track, whatever—and for some shows I might have to run three thousand of those off on the computer in a week. It’s increasingly redundant. I’ve got a nice Neve mixing desk, which I love but has been largely unused for the last year because there isn’t the time.

Matthew Herbert: The Whole Hog

It’s got more of a coffee table vibe at the moment. Talking of film and TV composition work, how does that stuff start? Do directors and producers know what they want, or do they come to you specifically because they don’t?

Well, slightly annoyingly, it’s different every time. You need to do two things. You need to develop a language with somebody in production, talking about the themes and what you might want from it, and then of course you’ve got the music itself and trying to work out what that is. In film you make the film with the director, but on TV you tend to make it with the producers. In TV there might be three, four, five different directors on it, and then of course the studio has notes and the broadcasters all have notes, so I think that’s why music is often a little uninspiring in TV, because there are just so many voices in it. Whereas with film you have the opportunity to build something from the ground up. A good example of that is the film The Wonder. I was sent the dailies for that, and I was speaking to Sebastián [Lelio], the director, who’s a friend of mine anyway, at the script stage about what it might sound like. Those rushes came in a year before I had to deliver the mix, so I had a year to think about it and try different things and to explore.

When you and Sebastián start engaging on the project, do you use adjectives to describe the world that you might create sonically, or do you only communicate to him in terms of sending him bits of music as he’s sending bits of what’s been filmed?

It has to be a variety of approaches, I think, because it’s very hard to talk about music. I might say to him, “I’m imagining an accordion, a distorted accordion flying round and round your ears,” and he might imagine that completely differently from me and from you and from anybody else hearing that description. It gets a lot easier to talk about music when you’ve got something in front of you, so I do try and get that fairly early. The only problem is that then it can be difficult to break away from that, so you can’t go too early because once they try and put it on a film it’s almost impossible to get off. They call it “demo love” or “temp love,” and you can hear it on huge American mainstream Hollywood films, and all the way through the industry, you can hear what was temped because you can hear what the composer has been asked to copy. There are well known examples on the Internet. So you want to hold off for as long as possible, but you need to do it early enough that they don’t temp with some other music.

Do you need a central motif, a magnetic idea that everything else sticks to, for a soundtrack?

That little phrase—dee diddle-de dee—that I’ve sung in the wrong key and badly out of tune, well, that unlocked [The Wonder] and it worked really well. And then I went on and wrote the whole film score and then about two-thirds through the process, I realized that I didn’t need it anymore. There’s a tiny hint of it in a couple of scenes that you would only notice if I pointed it out. It’s gone now, but it’s amazing how something that you were certain was “the thing” was actually just a key or a door to the actual thing, you know?

You mentioned “the thing”—is that what you’re searching for when you start working on a project?

Well, it’s not necessarily just a melody or a single thing, it could be different for every film. It’s quite melody-heavy with Sebastián’s work, but actually I did a film with him called Disobedience, with Rachel Weisz and Rachel McAdams, about an Orthodox Jewish community in Hendon in north London. We talked about it as a kind of sci-fi movie because this was a community that neither he nor I knew anything about, so it was a very alien world to us and we wanted to create a setting for this world. The “thing” on that film was what I called “air-conditioning.” I created this pad [a sustained tone or chord that underpins the mood of the whole] that’s got long, held notes and movement in it but doesn’t have a melody, it doesn’t have a tempo, it’s just a hum kind of thing. But that was the thing that unlocked it because you could build everything on top of that—a room tone, effectively, for the film to sit in.

“…a revolution has happened in music where we can make music out of anything—I mean, my new record is made out of a horse skeleton.”

Do you read scene descriptions to get a deep dive into characters and things like that?

I will read the script at the early stages and then once it’s shot I’ll ignore it, because you have to make work that fits what you have, not what you wish it could have been. You have to describe what’s there rather than what you thought was going to be there, particularly when it comes to characterization. You might read a particular character in a script in a certain way, and then once it’s played by an actor, it’ll change dramatically in ways you don’t think of, but—and this would be a bit of advice for anybody starting out in this world—you really, absolutely have to know precisely what’s happening narratively and what’s going on, because you’re embodying the whole feeling of the story and its priorities.

Can you give us a specific example of how that might play out?

I worked on a show about somebody who was stalked, and in a certain scene, the stalkee follows the stalker back to her house and sees that she lives in a sort of strange world, in poverty or in mess, and he thought that she was a lawyer living in a penthouse. It’s a very complicated relationship in which he’s spying on her, but she’s stalking him—and does she know that he’s following her, and who’s the victim in this situation? The shot might just be a man following a woman through a street, but how you score that has a massive implication on how people will perceive this relationship. For some scenes I might have four or five hundred conversations with Sebastián about what’s exactly going on and how much do we want to give away and “Is the music ahead of the picture or behind?” The Wonder is a good example of where the music isn’t ahead, it doesn’t tell you anything, but it sits above it, sort of floats above it. Whereas in another film, the music will be telling you, “This might look nice now, but just you wait: In 20 minutes it’s going to get really dark,” you know?

So that’s the horror score—Bernard Herrmann’s strings or something very well known is a pointer to future tragedy or danger.

Yes, so a classic thing where the music is in front of the picture would be someone walking up to open the door to their house and you might get burrrrrr, a low droney tone, and you think, Oh shit, something bad is about to happen, even though the character is just walking in normally. Whereas if the music is just like dum-di-dum, then someone opens the door and they get attacked, then the audience has the same perspective as the character. So that’s a huge power that you have with the music to shape audiences and your role in the storytelling. Another example might be if two characters are kissing for the first time: You might have really romantic music, but you’ve only got to put a minor chord in there under someone’s face and you know that that person isn’t into it as much as the other person. It’s a hugely powerful tool we have.

I understand you received dailies from Sebastián for The Wonder, which is presumably a great facility to have to be reacting to. Is that generally how it works?

If I’m sent dailies, I will write to them and not necessarily send it to anybody. On A Fantastic Woman, for example, I spent the first week just working out the tempo of the film. The lead character does a lot of walking, so I tried to figure out the tempo of this journey toward safety or happiness or calm or dignity or a space to exist or what have you. On The Wonder I spent a long time playing with different air instruments to get a sense of musical keys. Keys have a very different sound. There are billions and billions of bits of music written in C major because it’s easy to play on a guitar or violin. But with an F-sharp chord, which is still just a major chord but has a completely different feeling to it, there’s less music written in it, certainly classical music in the Western tradition. It’s not really until the Romantic composers started getting into the black notes, so there are immediately different references. If I was writing a score for a baroque or medieval or earlier thing, if I were to write in F sharp, it’s going to sound unusual and the audience won’t really understand why.

If you don’t use period-specific instrumentation, then you’re bringing it forward in time, maybe giving it 19th-century manners in a 14th-century setting, which is giving you a lot of power as well. What’s your take on making period music?

I don’t know if it’s a trap, but in Hollywood so much music still leans on an orchestra to carry a lot of emotional weight in scores. There are some peak moments in The Wonder that have a full orchestra behind them, but it’s a very strange situation, whereby a film like Minority Report, which was set 50 years in the future, will have almost identical orchestration to Gladiator, set in Roman times. This idea that a Wagnerian orchestral arrangement, particularly a large one for those big films, is somehow a universal sound that goes across centuries and disciplines and countries. I’m not a big fan of that approach, particularly now that a revolution has happened in music where we can make music out of anything—I mean, my new record is made out of a horse skeleton. In The Wonder there’s a little sound, weh!, that’s taken from one of Anna’s prayers—it’s just a syllable from one of her prayers. Then there are possibilities for storytelling. I think that’s best illustrated by the noises of scaffolding that you hear at the beginning of the film. I commissioned someone to make a series of sounds using scaffolding poles, like dragging them, banging them, blowing over the top of them. They’re all the way through the film, and at the beginning, it’s like a tolling bell.

So the film has this Brechtian construction to it—we’re seeing the fourth wall being dismantled in front of us. Do you think most people experience that subconsciously, at a level where people don’t know why they feel the way they do about a character or the scenery?

We process sound six to eight times faster than image, so we’re processing a lot subconsciously while we’re looking at an image. I would hope you’re building something from the ground up or from within rather than imposing it on top of the picture. I’d hope you’re assembling a whole group of details that have a meaning or a relevance, even if people can’t quite put a finger on it. But I think secondly, but fairly importantly, there’s a role in music, particularly at the beginning of a film, something that Sebastián is quite keen on and talks about a lot [which] is, “Come with me, let me tell you a story.” So for example, the opening titles of A Fantastic Woman have this slightly magical, fantastical, strange storytelling figure—and then you have this big, sumptuous melody that says, “This person is worthy of your attention, this is somebody whose story should be heard. She deserves a melody and we’re going to have 30 people in a studio play it for you.” And in fact that’s the loudest the music ever gets in the film with the orchestra.

Apart from the rave?

Apart from the rave, yeah! But that’s the loudest the music gets from the orchestral side of things, and it never gets that big again. What it does is it sets up a beautiful, special place with someone really gorgeous at the heart of it, who deserves this “Once upon a time.” And actually? It’s just a film about someone who wants their dog back, that’s the narrative force through the whole thing, and battling all the prejudices she goes through. But the capacity of the music there reassures the audience that somebody’s in control: “Trust us, you know. It’s going to be worth your time.”