The Polyphonist: Leslie Shatz

By Yonca Talu

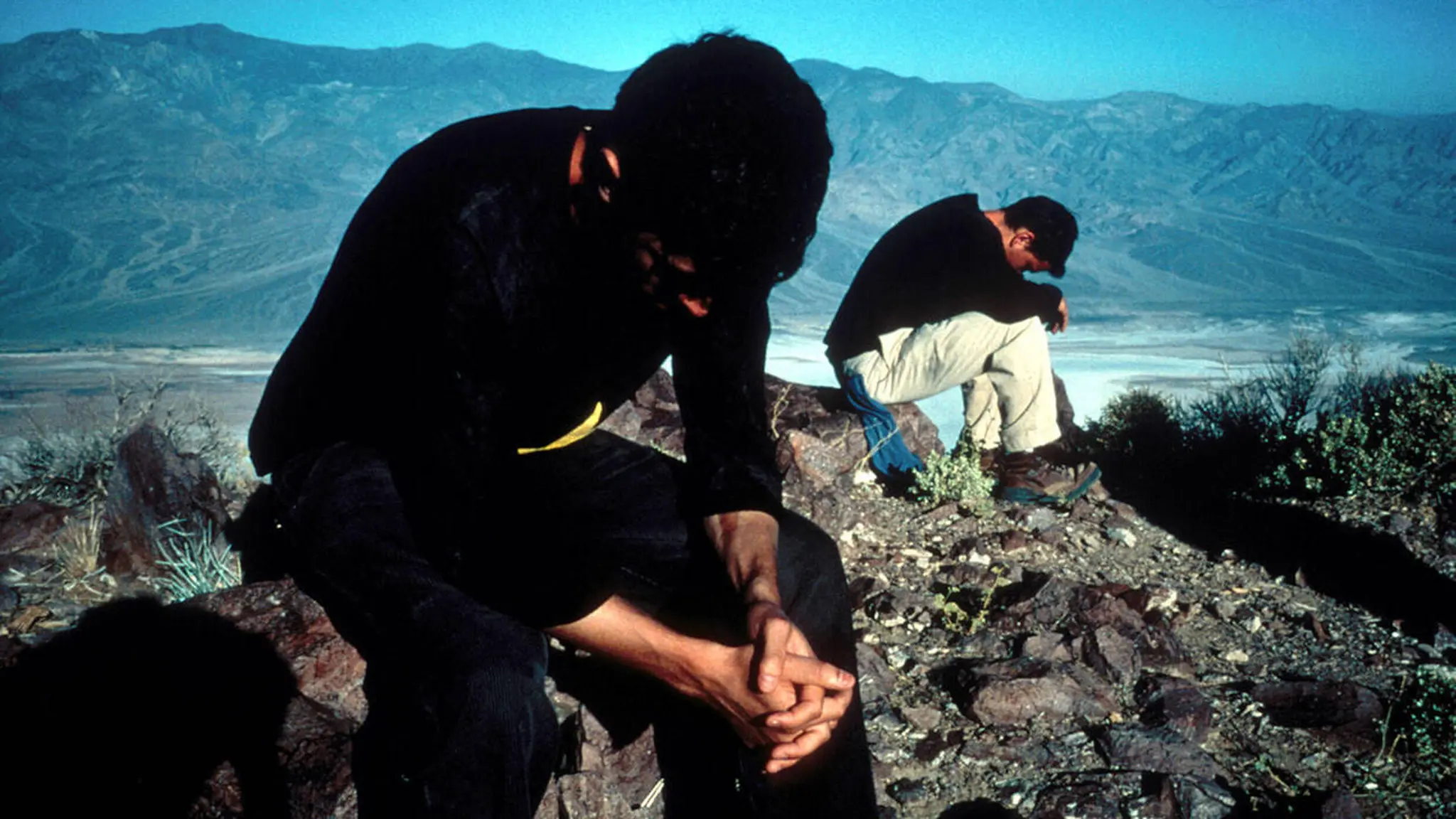

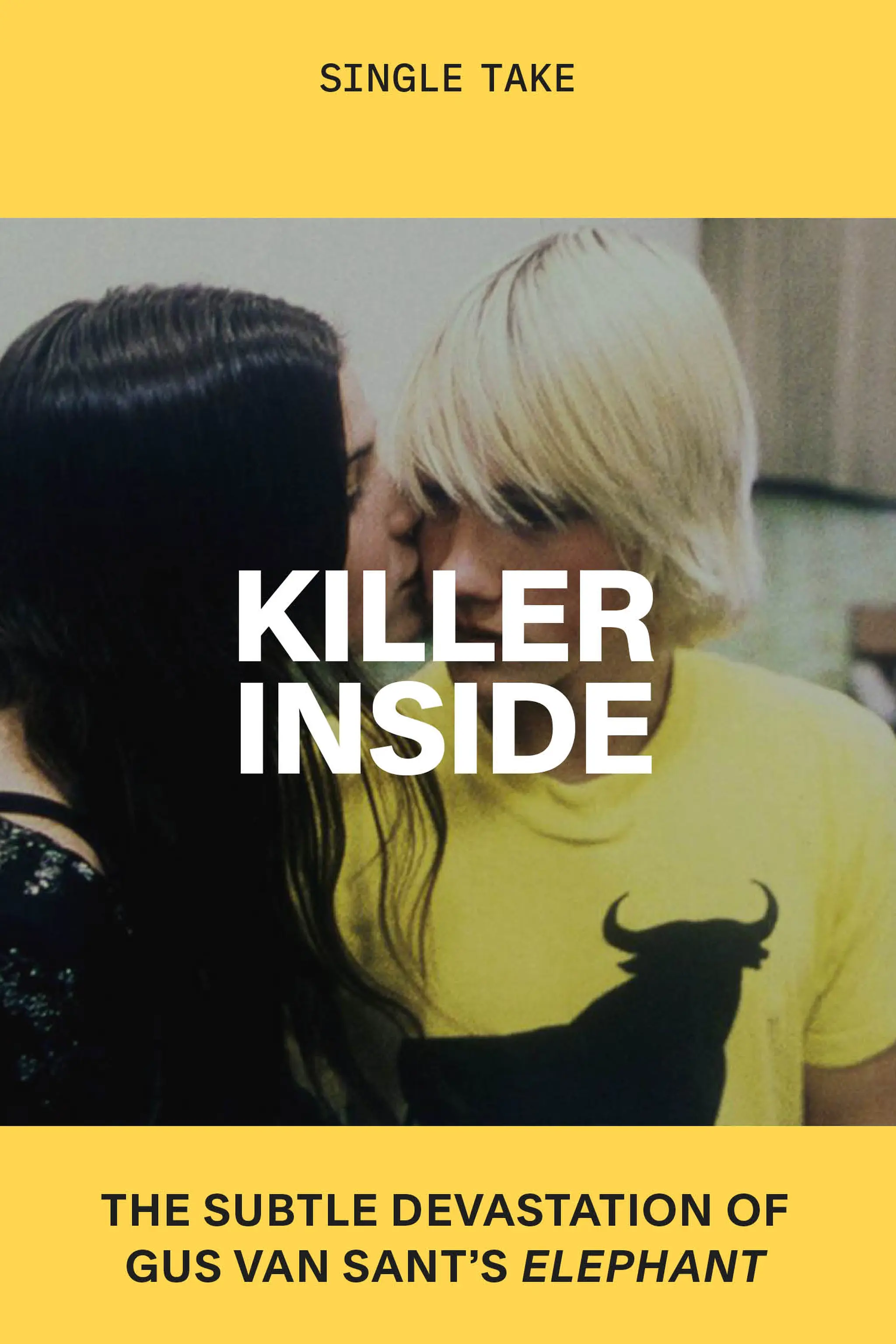

Elephant, dir. Gus Van Sant, 2003

The Polyphonist

Synthesizing instinct and innovation over a five-decade career, Leslie Shatz has established himself as one of the preeminent sound artists of American cinema

By Yonca Talu

March 26, 2023

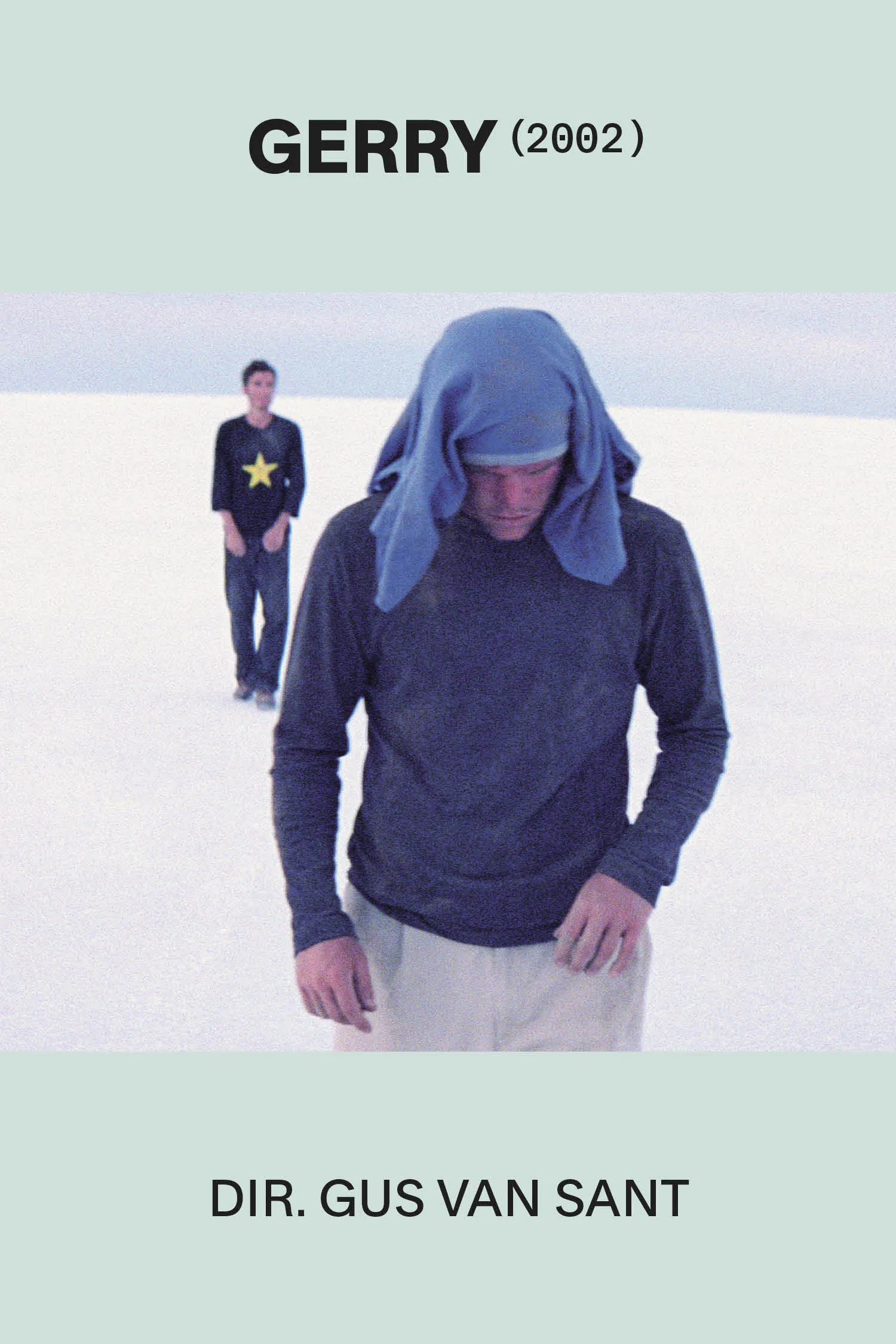

Few sound designers have a filmography as equally diverse and cohesive as Leslie Shatz. From his early days collaborating with Francis Ford Coppola and his decades-long partnerships with Gus Van Sant, Todd Haynes and Kelly Reichardt to his recent work on acclaimed indies like Brady Corbet’s Vox Lux (2018) and Kitty Green’s The Assistant (2019), Shatz is dedicated to employing sound as a key element of film form rather than a mere storytelling device. Influenced by musique concrète and the work of his mentor, trailblazing editor and sound designer Walter Murch, Shatz is best known for the hypnotic soundtracks he composed for Van Sant’s long take–driven ‘‘Death Trilogy,’’ comprising Gerry (2002), Elephant (2003) and Last Days (2005). In these films, he favors a heightened, contrapuntal use of sound to immerse us in the deteriorating psyches of Van Sant’s characters and reveal the menace that looms over the seemingly harmless environments they traverse. Shatz spoke to Galerie about his formative film experiences, the risk-taking elements of collaboration and how he navigates the sensibilities of different directors.

From left: Gerry, dir. Gus Van Sant, 2002; Last Days, dir. Gus Van Sant, 2005; Bram Stoker’s Dracula, dir. Francis Ford Coppola, 1992; Far from Heaven, dir. Todd Haynes, 2002; First Cow, dir. Kelly Reichardt, 2019

You originally wanted to pursue a career in music. How did you end up working in film?

I started out wanting to work in music, but I wasn’t much of a musician. I had a vaguely technical bent, so I tried to get a job as a music engineer in my hometown, Los Angeles. But I didn’t succeed. As a fallback, and though I wasn’t really a cinephile, I got a job at the American Film Institute. There I saw, among other films, George Lucas’s THX 1138 [1971], which blew my mind. Walter Murch’s sound design was so inventive. It sounded like musique concrète [i.e., music made with sounds rather than instruments]. I’d recently been turned on to Pierre Henry, one of the fathers of musique concrète, and I thought, Well, maybe I can work in film and make music with sound. That led me to an admiration for Walter Murch.

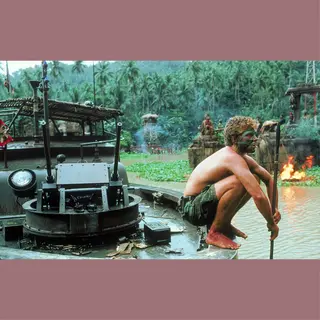

You went on to collaborate with Walter Murch as a dialogue editor on Francis Ford Coppola’s Apocalypse Now [1979]. How did you come on board that era-defining film, which also happens to have inaugurated the sound designer title?

Yes, for his work on Apocalypse Now Walter became the first person in film history to get a sound designer credit. Now everybody’s a sound designer! [Laughs] In the early ’70s, I organized a trip to San Francisco to meet Walter, who was very nice. In the process I was able to get an interview with Francis Ford Coppola. He said, ‘‘Oh, you’re hired to work at my production company, American Zoetrope.’’ It was incredible! I was so excited. But when I showed up for work on Monday, his business person said, ‘‘He’s crazy—we don’t have money to hire you! I’m sorry. This was all a big mistake.’’ I went back home crushed. Still, I set my sights on working with Francis. When he was making Apocalypse Now, there were all sorts of news articles about how everybody on location in the Philippines had lost their minds. That whetted my appetite even more. I eventually found out they were looking for a dialogue editor. So I hurried to San Francisco and took an interview with the film’s sound team, who liked and hired me. I was a good fit for them because I wasn’t heavily entrenched in the Hollywood film industry, which Francis distrusted and had moved away from.

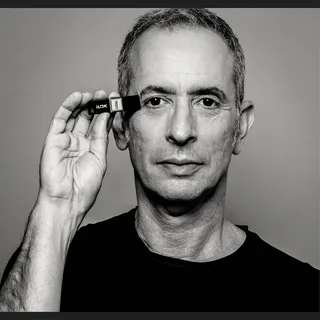

From left: sound designer Leslie Shatz (photo by Jeong Park); Apocalypse Now, dir. Francis Ford Coppola, 1979

How closely did you work with Francis Ford Coppola on the film’s dialogue edit?

The film was shot in battlefield conditions, so most of the dialogue was unusable. We went to L.A. to do ADR [i.e., automated dialogue replacement]. I remember very well my first ADR session with Francis and the film’s star, Martin Sheen. We were in the recording studio and Francis said to me, ‘‘You run it. I’m just gonna sit back here, and I’ll tell you if I hear anything I don’t like.’’ I was petrified. I was in my early 20s and had never addressed an actor of such stature, let alone led an ADR session. But somehow I found the courage to do it. At first Martin Sheen was a little suspicious. He’d deliver a line, and I’d say, ‘‘That’s good. Let’s move on.’’ But he would be like, ‘‘What do you think, Francis?’’ And Francis would be like, ‘‘Oh, yeah.’’ Eventually Martin Sheen skipped that step. The next day Francis fell asleep on the couch. And the third day he didn’t even show up. [Laughter] He didn’t show up because ADR is very boring. You have to pick the lines apart over and over again and really listen to the subtleties of the speech and the recording. But I loved it, and I got to work with Francis’s actors.

It’s amazing how much he trusted you.

It is. He had an instinct for people, and if he trusted you, you could go as far as you wanted with him. You know, he gave me a big opportunity on Bram Stoker’s Dracula [1992]. The sound designer he normally worked with, Richard Beggs, had taken another film. So he asked me to be his sound designer.

So what was it like to sound design that nightmarish, kaleidoscopic film? How experimental did Francis Ford Coppola encourage you to get?

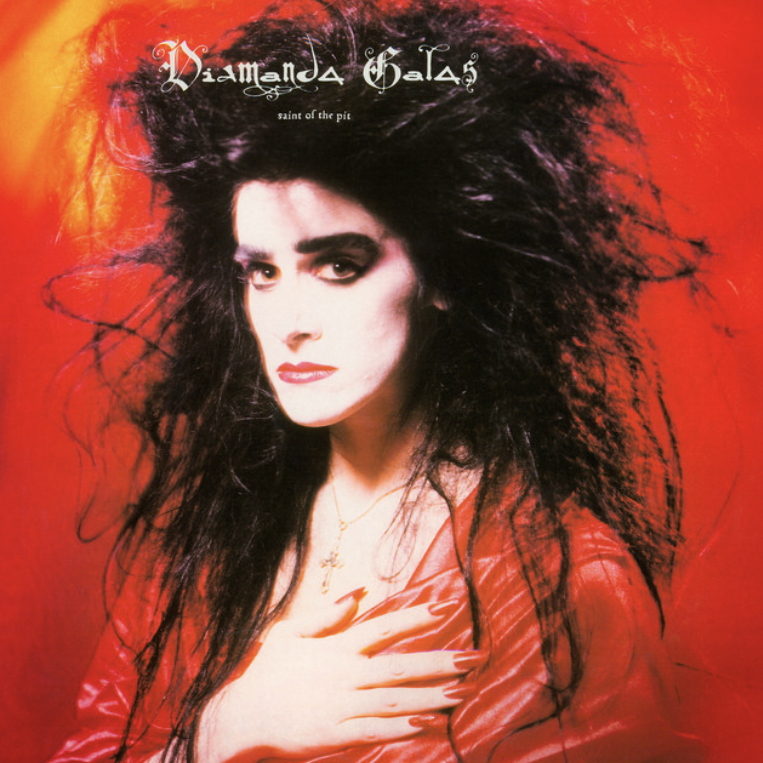

He wanted me to get as experimental as possible, which was a problem. When somebody takes all your limits off, like he did, it can be so scary. I was paralyzed for the first week. In fact, I had to start seeing a therapist. I mean, Francis was my God, my total cinematic idol, and I didn’t want to disappoint him. But I eventually got past my fear and anxiety and went into the weeds. I wanted to use the human voice in my sound design in a completely insane and distinctive way. And I came across the work of vocal artist Diamanda Galás, which really fits that bill. She did recordings for Dracula, and when Francis heard them, he got so excited. He was like, ‘‘Yeah, this is it. I want more!’’

I love that sequence where Jonathan Harker (Keanu Reeves) walks into Dracula’s castle and we hear an eerie symphony of drawn-out gasps and moans.

Yeah. When we previewed the film for the studio executives, they said, ‘‘Dracula’s castle is not scary.’’ So I started experimenting with Diamanda Galás’s breaths and used reverse reverb on them to create a mood of suspended terror. Then we did an audience preview, and people were terrified, which is the best compliment for a sound designer!

Deliver Me by Diamanda Galás

Around the same time as Dracula, you began your collaboration with Gus Van Sant on Even Cowgirls Get the Blues [1993]. How did you two meet?

In the late ’80s, Gus came to San Francisco to interview me to be his sound designer on Drugstore Cowboy [1989], which unfortunately didn’t happen for scheduling reasons. But we spent an entire day together in San Francisco, talking about musique concrète and Francis. Gus told me he’d been an extra on One from the Heart [1981] and had cast Matt Dillon in Drugstore Cowboy because of his role in Rumble Fish [1983]. He was really into Francis, like me! [Laughs] We became friends from that moment on and started working together a few years later on Even Cowgirls Get the Blues. At the time Gus frequently changed his collaborators. But I’ve done pretty much all of his films, which is something I always marvel at.

As Gus Van Sant’s sound designer, how did you experience his radical shift from crowd-pleasing movies like Good Will Hunting [1997] and Finding Forrester [2000] to the avant-garde ‘‘Death Trilogy’’ films, Gerry, Elephant and Last Days?

On Good Will Hunting, Gus was a gun for hire. Matt Damon and Ben Affleck had written the script, and one of them wanted to direct it. But Harvey Weinstein, who executive produced the movie, didn’t let him. So they said, ‘‘What about Gus Van Sant?’’ That’s how Gus came on board Good Will Hunting, which was an enormous success and led him to be hired to direct Finding Forrester. But afterward things kind of slowed down for him, and he didn’t get as many offers. Then he sent me Gerry’s script, which was, like, 20 pages long. He said, ‘‘Well, I didn’t even want to write a script, but the Writers Guild of America insisted that I have one.’’ [Laughs] To be honest, when I read the script, I couldn’t see Gus’s vision. I thought, Is this film really going to work, and are people going to be interested in it? But after I watched Gerry several times, I realized that it was a different moviegoing experience. I was making up the story in my head as the film went along. It wasn’t about, ‘‘This happens, then that happens.’’ There’s some of that in there, but there are also very long tracking shots in which the characters [played by Matt Damon and Casey Affleck] are just walking and walking in the desert. At first you’re like, When is this shot going to be over? But then you get into a meditative feeling and escape into your own story.

An example of such a tracking shot is the one in which the two men, framed in profile, walk in unison for minutes. After a while, the rhythm of their crunchy footsteps becomes a hypnotic melody.

Yeah. Harris Savides, who shot Gerry, told me how much he liked the sound in that scene—and in the film in general—which meant so much to me.

Did you use Foley in that scene?

We did. We couldn’t use the production sound because you could hear the camera dolly being pushed on tracks across the desert floor. But we had a really good Foley artist, Andy Malcolm, who was able to re-create the men’s footsteps. I went up to Canada to work with him, and we experimented with different surfaces. I think we used cornstarch, which is a very good substitute for thick desert sand.

I’ve read that you visited the desert locations of Gerry to soak in their sounds.

Yes, I went to Death Valley during the shoot to listen to and record sounds. When you go there, you cannot believe how quiet it is. It is so quiet. The human body doesn’t want its sensory input to be too far off the scale one way or the other. So in a place like Death Valley, your brain creates sound to make up for the lack of it. You hear a ringing in your ears. You hear your heartbeat. You also hear sounds from very far away, like when Matt Damon’s character hears a truck at the end of Gerry and realizes that there’s a road in the distance. Any wildlife sounds are amplified too. There will be, like, one cricket or bird, and it’ll just stand out. You can record those sounds and use them. But what hearing them in person gives you is an aesthetic idea. My job as a sound designer is not to imitate but to re-create that aesthetic idea with my tools. On Gerry, I had to reach deep inside to convey how certain sounds are amplified in Death Valley, which is something you can only understand if you go there and actually experience it.

Sounds of Death Valley in Gerry

“In a place like Death Valley, your brain creates sound to make up for the lack of it. You hear a ringing in your ears. You hear your heartbeat.”

Did you also spend time in and listen to the acoustics of the Portland, Oregon, high school where Elephant was shot?

No. But I did suggest that we use an ambient stereo recording technique called M/S, for Mid/Side, to capture the acoustics of the school’s hallways. And our production sound mixer, Felix Andrew, said okay. It was kind of hard for him because he now had two boom poles to deal with: one with a regular mic and another one with an M/S mic. He also likes to operate the boom himself, so he had a lot on his plate. But he’s very agile and he pulled it off. Thanks to the use of M/S, the film has a deep sense of resonance, which makes it so haunting. Everybody remembers that feeling of being in high school and hearing a teacher droning on and on down the hallway, like in Elephant.

What else did the use of M/S add to Elephant’s soundtrack?

If M/S is not properly decoded, it turns from an ambient into a left/right stereo. All of a sudden the audio channels are reversed, and the sounds come out of the wrong speaker. That happened with some of Elephant’s dailies, and when Gus saw them, he was like, ‘‘This is fantastic!’’ He thought it added to the film’s confusion to see characters on the right side of the frame and hear them through the left speaker. Later the people who were doing Elephant’s foreign dubbing called us up and said, ‘‘We don’t understand why these voices are on the wrong side.’’ [Laughter] And we were like, ‘‘That’s the way it is. You gotta go with it.’’ To them it was a mistake, but not to Gus. He just embraced it.

The film is full of sounds that would typically be regarded as technical mistakes.

Yes, there are a lot of deliberate imperfections, like mic bumps and off-camera sneezes. After Gus and I had made enough progress with the sound mix, we played it to HBO Films, who produced Elephant. I remember listening to the mix at HBO and telling myself, ‘‘Wow, this turned out really good. When the lights come up, just be modest.’’ [Laughs] But when the lights came up, the HBO people turned around and said, ‘‘What the hell was that? Was that the mix or the dailies? Where’s the high school walla [i.e., crowd murmur]? Where’s the Foley? Why do we hear the crew? Why are some sounds on the left when they should be on the right?’’ [Laughter] They just ripped the mix apart while looking at me.

They were pointing the finger at you.

Yeah. They were like, ‘‘This is not professional. You should start from scratch.’’ But Gus kind of laughed them off. He wasn’t going to be cowed by them. After that meeting, he sent the same version of the film to the Cannes Film Festival selection committee, who said, ‘‘The film is amazing, and we particularly love your use of sound.’’ When the HBO people heard that, they were like, ‘‘Don’t worry about what we said. We see what you’re doing—just finish the mix.’’ [Laughs] To their credit, they didn’t try to interfere, though their initial remarks were everything that I would have had a note on. My instinct would have been to remove all the imperfections and add more high school–related sounds. But Gus rejected those conventions and followed his intuition, which resulted in an iconic soundtrack.

What makes the soundtrack so compelling is how seamlessly you interweave layers of diegetic and nondiegetic sounds. In the Steadicam shot that follows the Nathan character (Nathan Tyson) from the football field into the school, you even use sounds that seem to have been recorded in a cathedral and a train station.

Those sounds actually come from a piece by soundscape composer Hildegard Westerkamp [i.e., Türen der Wahrnehmung, aka Doors of Perception]. We had a whole library of musique concrète and soundscape recordings, some of which we used in the film. But the main layer of that Steadicam shot is of course Beethoven’s Moonlight Sonata. Alex Frost, who plays Alex, one of the killers, had been taking piano lessons. During breaks on set, he would play Beethoven on the school’s piano. That’s what gave Gus the idea to use Beethoven’s music in the film, and I couldn’t imagine Nathan’s scene without it.

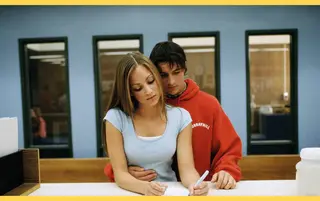

From left: Carrie Finklea Finn and Nathan Tyson in Elephant; Michael Pitt in Last Days

Another scene with a haunting sound design is when Benny (Bennie Dixon) wanders through the school as the shooting is happening. Rather than accentuate the chaos we see onscreen, you mute the voices and soften the footsteps of the students fleeing the gunshots. How did you navigate that sequence?

I remember putting myself in Benny’s shoes and thinking, How would I feel? I’ve never had an experience like that [i.e., like a school shooting], but it seems to me that your mind would be frozen. You would be detached from what’s in front of you. That’s what I wanted to convey in that sequence by decoupling the sound from the image. When you do that, you engage the viewer’s subconscious. You invite them to make their own connections rather than simply follow the story.

You provoke sensations.

Yes. One of the first directors to use sound contrapuntally was [Vsevolod] Pudovkin, in his film Deserter [1933]. In the late ’20s, filmmakers were horrified by the arrival of sound. They thought that movies were going to become stage plays. So Pudovkin and his fellow Soviet directors, [Sergei] Eisenstein and [Grigoriy] Aleksandrov, created a manifesto [i.e., ‘‘A Statement on Sound,’’ 1928]. They wrote that a film’s sound should always be in counterpoint to and never synchronized with its images. That was the only way, they thought, to keep movies from becoming stage plays. They were right, and I tried to do the same on Elephant and some of Gus’s other films.

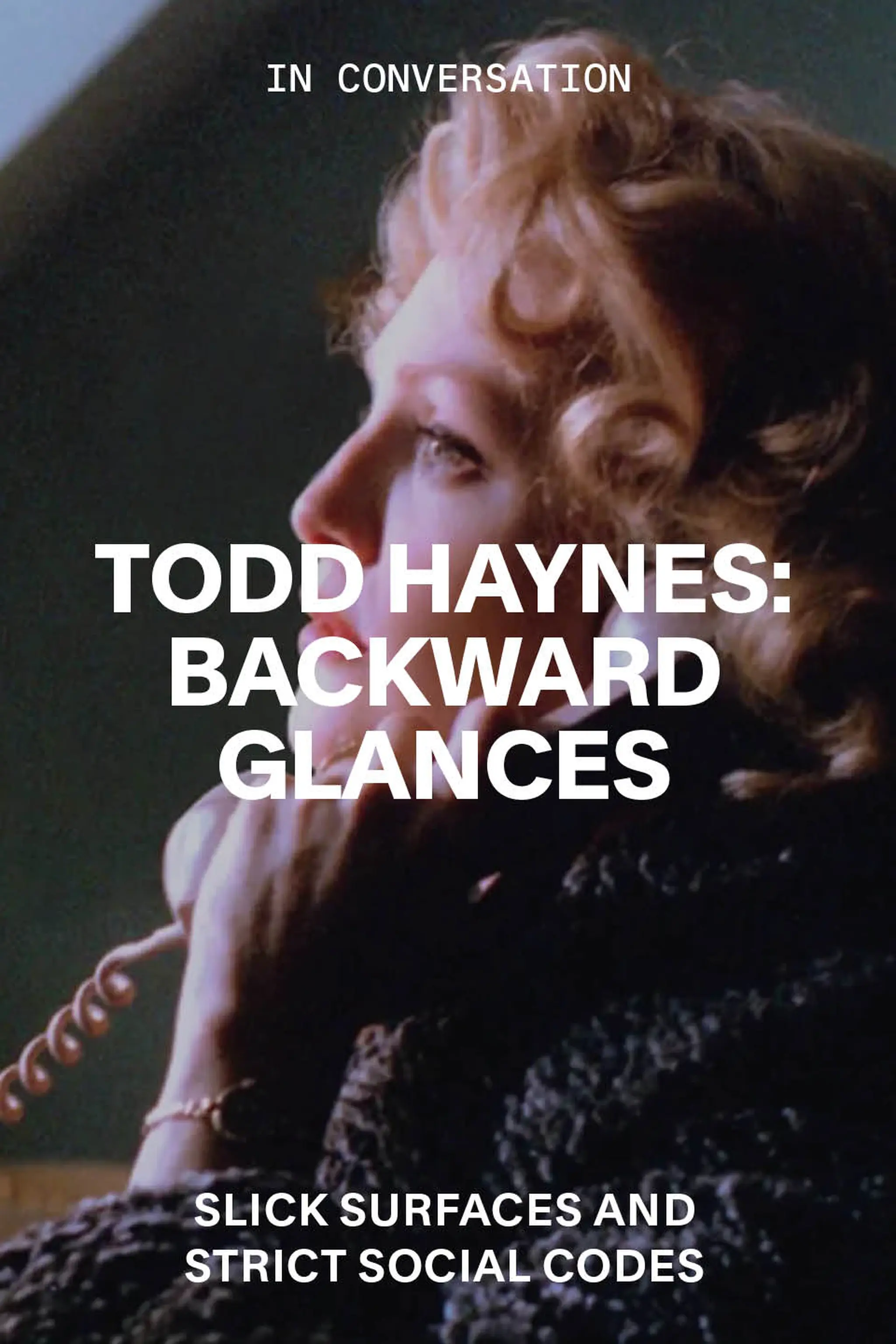

Your partnership with Gus Van Sant also led you to meet two of your other frequent collaborators, Todd Haynes and Kelly Reichardt. Not only are they all friends and based—or in Van Sant’s case, formerly based—in Portland, but they also share a similar sensibility when it comes to using sound both as a narrative and an aesthetic tool. How would you compare collaborating with them?

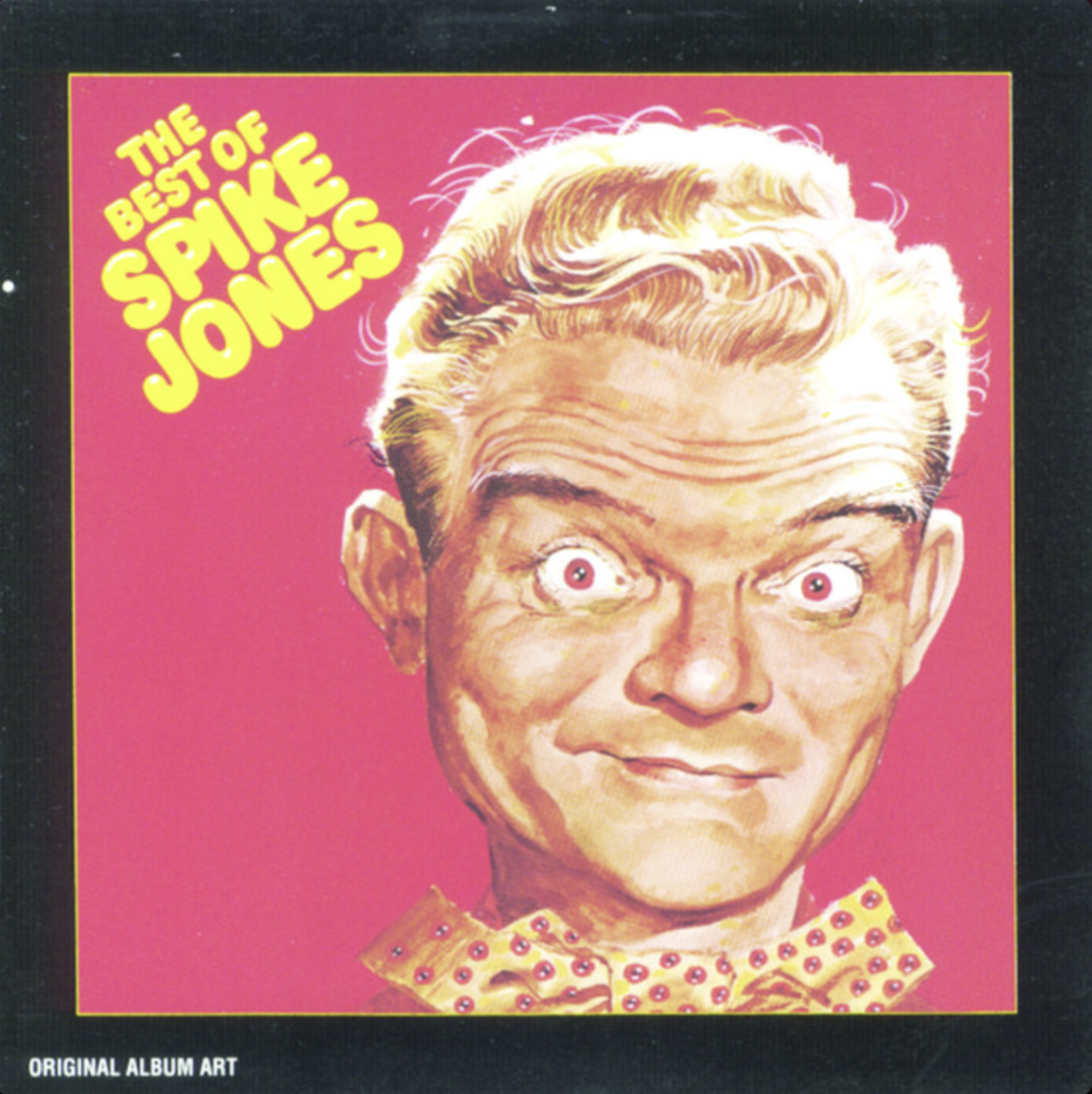

Oh, they’re very different. Todd was looking for a sound designer for Far from Heaven [2002], which is such a beautiful film. He called Gus and asked, ‘‘Who should I work with?’’ And Gus said, ‘‘Leslie.’’ Todd’s biggest difference from Gus is that he does not operate on impulse. You ask Gus, ‘‘Why did you do that?’’ And he goes, ‘‘I don’t know—it seemed good.’’ [Laughter] But Todd would never say that. He plans out his films very carefully, with look books and references, and has strong reasoning for every choice he makes. He likes sound to be more of a supporting player to the images, though he had a different approach on Wonderstruck [2017]. In that film, he embraced the contrapuntal, nondiegetic use of sound to emulate the psychological mood of his two deaf protagonists. We drew inspiration from comic musician Spike Jones, who used things like pots and pans as instruments. It was a very collaborative process and we had a really good time. But I hope Todd doesn’t think I’m crass. [Laughs] He’s very much into subtlety, so I try to work inside that feeling with him.

What about Kelly Reichardt? What stands out to you about her working method?

I met Kelly through Todd, who’s one of her closest friends and a producer on a lot of her films. Kelly’s very precise. When I put bird sounds in her films, she’s like, ‘‘Are these birds correct for our location?’’ And I’m like, ‘‘I don’t know.’’ [Laughs]

She cares about verisimilitude.

That’s right. Now I have an app, Merlin Bird ID, developed by Cornell Lab of Ornithology. You can play bird sounds to it, and it tells you the name of the bird and where it lives. I use that app on Kelly’s films because, fair enough, I don’t want to insult anyone by putting a bird from Hawaii in a scene in Oregon. [Laughs] But Kelly’s very fun to work with and be around. Like me, she’s a major dog person. I would bring our dog, Emily, to the sound mix of First Cow [2019]. She’s not really a people dog, but Kelly was determined to win her over. Whenever I was busy doing stuff that didn’t involve Kelly, she would get on the floor and try to befriend Emily. By the end of the mix, Emily was sitting in her lap, and she was like, ‘‘This has been a successful mix!’’ [Laughter]

Cocktails for Two by Spike Jones & His City Slickers