Chantal Akerman's Final Word

By Kaleem Aftab

Jeanne Dielman, 23, quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles, dir. Chantal Akerman, 1975

the Final Word

CHANTAL AKERMAN IS NOW HAILED AS ONE OF CINEMA’S GREATS. SO WHY WAS SHE SHUNNED IN HER LIFETIME?

By Kaleem Aftab

October 4, 2023

In many ways Chantal Akerman is the Emily Dickinson of cinema. Arguably it’s only since her death from suicide, in October 2015, that cinephiles and the wider public have genuinely begun appreciating Akerman’s work. One example of this posthumous acclaim came in 2022, when her 1975 feminist masterpiece Jeanne Dielman, 23, quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles was voted the “greatest film of all time” by critics in the once-every-decade poll by the British journal of record Sight and Sound, displacing Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo (and before that, Orson Welles’s Citizen Kane) and making her the first female director placed on top of this illustrious list.

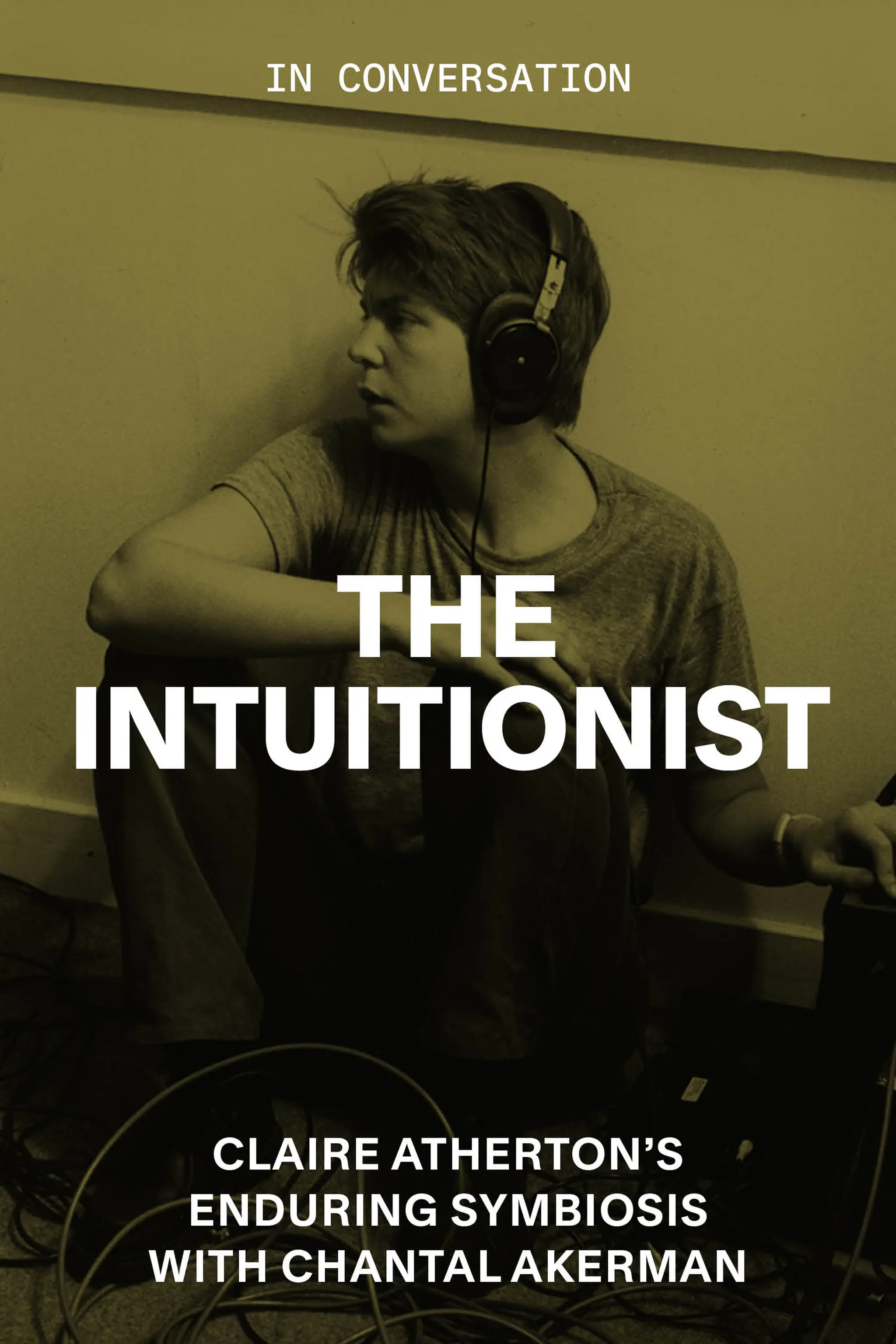

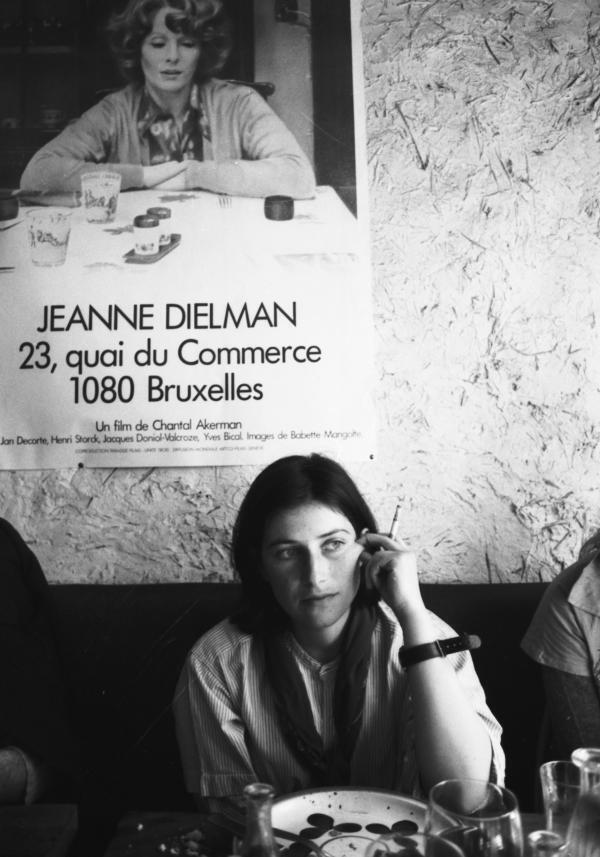

Chantal Akerman (photo by Marion Kalter)

Akerman made the film when she was 25. At the time, the reaction from the public was one of bemusement. Cultural shows and comment pieces debated whether today’s critics were out of touch by voting for a 200-minute film that most people had never seen (or even heard of). The debate focused on the film being “unknown” rather than the gender politics behind this great director’s marginalization. Also, it missed how this ignorance of her cinematic voice ensured that Akerman had fallen out of love with cinema before her death.

At least that’s what I’ve come to feel, especially when looking back at an interview I conducted with the filmmaker at the Venice Film Festival in 2011.

Her frustration with the mechanisms of cinema was palpable when talking with Akerman the day after the world premiere of what turned out to be her final narrative feature film, Almayer’s Folly. The wind was swirling around the garden of the Quattro Fontane hotel on the Lido, mirroring how the then 61-year-old seemed exhausted by the rigmarole of making movies: financing, production battles, distribution and exhibition. She must also have been disheartened by the minimization of her film at the festival. A loose adaptation of Joseph Conrad’s debut novel about a Dutch trader searching for treasure in Southeast Asia, it received a mixed reaction from the press and muted fanfare. The festival hadn’t exactly treated Akerman with reverence either: Here she was, a cinematic legend (Jeanne Dielman was 36 on the 2012 Sight and Sound list), and this new, daring work about racism, gender and the ongoing effects of colonialism was playing in an out-of-competition slot. There was no regard for her long record of groundbreaking cinema. Contrast that to the continuing treatment of filmmakers like Jean-Luc Godard, Wim Wenders and Ken Loach, whose works have been selected for prestigious festival competitions even when they are subpar efforts.

Should it have been a surprise that the Belgium-born director told me that she was happier working in a gallery space than for the cinema cretins who were making her life as a filmmaker miserable? When working with galleries, “you don’t have to write a text, a big script to give to all these annoying producers and financiers, who will say that scene doesn’t work,” she said. “Look at Almayer’s Folly as a case in point. I was writing the script until the day we started shooting the movie. What the producers assessed was a script that was so different from the shooting script. So they end up saying things like, ‘At the beginning [script stage], it was drier, more like Conrad.’ They have something [a script], and they don’t understand that it can evolve.” In stark contrast, creating video pieces for gallery spaces was a liberating process for Akerman. “What I enjoy most is that it’s not so burdensome with a big crew,” she explained. “I film the images myself most of the time. I work with my friend [Claire Atherton], who is the editor, in my house. I start without any preconceived ideas, not knowing where it will go, and suddenly the piece is there. It’s so refreshing compared to making a movie.”

Delphine Seyrig in Jeanne Dielman, 23, quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles

It was the celebrated art curator Kathy Halbreich, formerly of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston and the Museum of Modern Art in New York, who hatched the idea of liberating Akerman. “She thought my films were close to art, and I thought I’d try [to make something for a gallery], but I had no idea,” Akerman said. “It was a big success, and I enjoyed it because it was light.” Light is more a reference to commissioning and distribution than the time spent working on the project. It was a full four years after Halbreich first visited the director in Paris in 1989 with a proposal for Akerman to record her impressions on the fall of the Berlin Wall until she made a film destined for a gallery, and another two years before it became part of a show. Halbreich, a Jeanne Dielman fan, wrote in Artforum about why she thought Akerman would be suitable for this proposed project: “I wasn’t interested in journalism’s objective pose so much as in the close intertwining of the personal and the political found in Akerman’s films.... Since intimacy was at the center of all her films, despite the distance imposed—and disinterestedness presumably engendered—by the medium shots she preferred, I imagined she could make a work that gave this unfolding history the peculiarity and texture of a diary.”

Akerman, as is the hallmark of a visionary auteur, had other ideas. She told Halbreich that she was interested in making a piece rooted in a project concept she had for a personal essay on the current state of countries in Eastern Europe, ones still profoundly marked by the events and fallout of the Second World War and therefore affected by the collapse of the Soviet empire. One imagines that Halbreich, so enamored of how Akerman used time and space to make the quotidian details of a woman’s household chores so memorable, political and impactful in Jeanne Dielman, would have agreed if Akerman had wanted to make a film about graffiti drying on the Berlin Wall. The result was the nearly wordless D’Est (From the East), which first appeared as a film in 1993 before being expanded and developed to become the gallery work Bordering on Fiction: Chantal Akerman’s “D’Est,” which debuted at the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis in 1995. The gallery piece occupied three contiguous but distinct spaces, starting with the 110-minute film played with ambient sound and no dialogue. Spectators would then spin off into eight different sets of three monitors, each playing a poignant four-minute excerpt of the film, which Halbreich describes as “spatializing the technique of cross-cutting,” before the journey ended in a dingy room lit only by a monitor on the ground showing streetlamps at night, with the voice of Akerman reading the second commandment, prohibiting idolatry, in French and Hebrew. While the cinematic version was about the displacement of populations always on the verge of disaster, the dialogue added to the gallery installation questioned her own relationship with Judaism and whether the act of making a film ran counter to doctrine.

Akerman’s work reframes repetitive and mundane acts as necessary to avoid moments of contemplation caused by downtime, when feelings of anxiety and suicidal thoughts are more likely to overcome us. The auteur’s struggles with depression and a bipolar diagnosis were well known within her circles. Just think of how Akerman may have interpreted humanity’s current addiction to screen time and repetitive scrolling as part of this need for distraction. Many have speculated and written about Akerman’s depressive solitude. But there is a porous border between interpretation and amateur psychoanalysis. One common assertion is that Akerman’s anxiety is a condition inherited from the trauma suffered by her parents, Polish Jews who had lived through the horrors of the Holocaust. Her mother was in Auschwitz for 18 months, and Akerman’s maternal grandparents died there. Did her parents suffer from guilt? Akerman herself reinforces this idea of inherited history in the made-for-TV documentary Chantal Akerman par Chantal Akerman, in which she suggests that she embodies the rebellious spirit of her grandmother, a proto-feminist painter.

Almayer's Folly, dir. Chantal Akerman, 2011

There is also the much-asserted idea that Akerman’s films were about her mother’s tight stranglehold on her. The case is easy to make, notably because her mother, Natalia [or “Nelly” ], was a constant figure in the filmmaker’s oeuvre, whether playing herself or a character, such as in Toute une nuit from 1982. Akerman’s 1976 film News from Home has the director reading letters her mother wrote to her, and her mother’s letters excusing her daughter from school are featured in Portrait d’une jeune fille de la fin des années 60 à Bruxelles (Portrait of a Young Girl at the End of the 1960s in Brussels; 1994). Akerman included letters from both her mother and grandmother in the gallery piece Walking Next to One’s Shoelaces in an Empty Fridge, the title referring to the fact that the director never tied her shoelaces and her parents’ worry that she was anorexic when she was growing up, which the artist believes was her mother’s projection, a result of being starved in concentration camps. Akerman’s final work, her documentary No Home Movie, first shown at the Locarno Film Festival, features her conversations with her mother in the months leading up to her mother’s death. Shortly after the film was released, Akerman took her own life. Almost immediately, her final film was recontextualised by critics as a demonstration of how her mother was the creative impulse for her work, a person without whom life lost meaning.

If her mother came to embody femininity throughout Akerman’s work, would it also be true to argue that her father, Jacques Akerman, represented masculinity? It’s a less-examined relationship, occupying less space in her work. Even Rabbi Delphine Horvilleur, who delivered Akerman’s eulogy at Père Lachaise cemetery, posited the filmmaker’s creations as reflections on her mother, saying that Nelly had “inhabited all [Akerman’s] creations to the utmost.” And yet, even though her final nonfiction gallery work featured her mother, her ultimate narrative feature, Almayer’s Folly, was driven by her need to make a movie about a father-and-daughter relationship. “It was not easy with my father,” she told me between puffs on a cigarette. “He wanted me to have a normal life and to get married. Well, I was gay! He pretended not to know, but he felt it.”

“With each work, she said, she became more liberated in her directing and less reliant on precision or manufacturing the ideal frame.”

This belief mirrors the crux of Almayer’s Folly and is where we can find Akerman’s attraction to Conrad’s novel. Set in 19th-century Borneo, the book is about a poor businessman who is married to a Malayan native and dreams of finding a goldmine and riches. They have a daughter, Nina, whom Almayer seems to dote on, believing that he is doing everything to give her a better life. But Akerman read a more profound meaning into Conrad’s prose and repurposed the book to tell the story from the perspective of the Dutchman’s biracial daughter. Knowing she was frustrated with her father for ignoring her sexuality and pushing his worldview on her, it’s revealing how she interpreted Almayer’s Folly. “Well, he had a dream for himself. And in fact, he was projecting that dream onto his daughter, who didn’t have that dream at all. And it was, he thought, a way of loving her. But in fact he was not loving.”

Akerman’s interpretation also opens up questions about the male and female gazes. “You know Conrad, he is about men,” she observed. “If you read the book, it’s five pages about the girl, and that’s it. The girl was not in the boat or coming out of jail in the novel, but the girl took an enormous place in the movie. I think I made a film about the inequality between men and women.” Power imbalance and society’s treatment and view of women is a central theme in her work, but Akerman claims that was happenstance rather than intentional. “I started before all those gender-studies courses developed. I was not even thinking of that; it came out very naturally. And then they took all my films in gender study programs.” It is hard to believe that Akerman’s rewriting of film language and abandonment of plot was not a concerted rejection of cinema tendencies that had been created, defined and analyzed by men. Her self-deprecating views seem humble, considering that journals such as Camera Obscura describe her as “arguably the most important person in feminist film culture.” Not bad for someone who quit film school after three months to make her first short movie. The artist has even described her most important “feminist” movies, Jeanne Dielman and Je tu il elle, as too dogmatic.

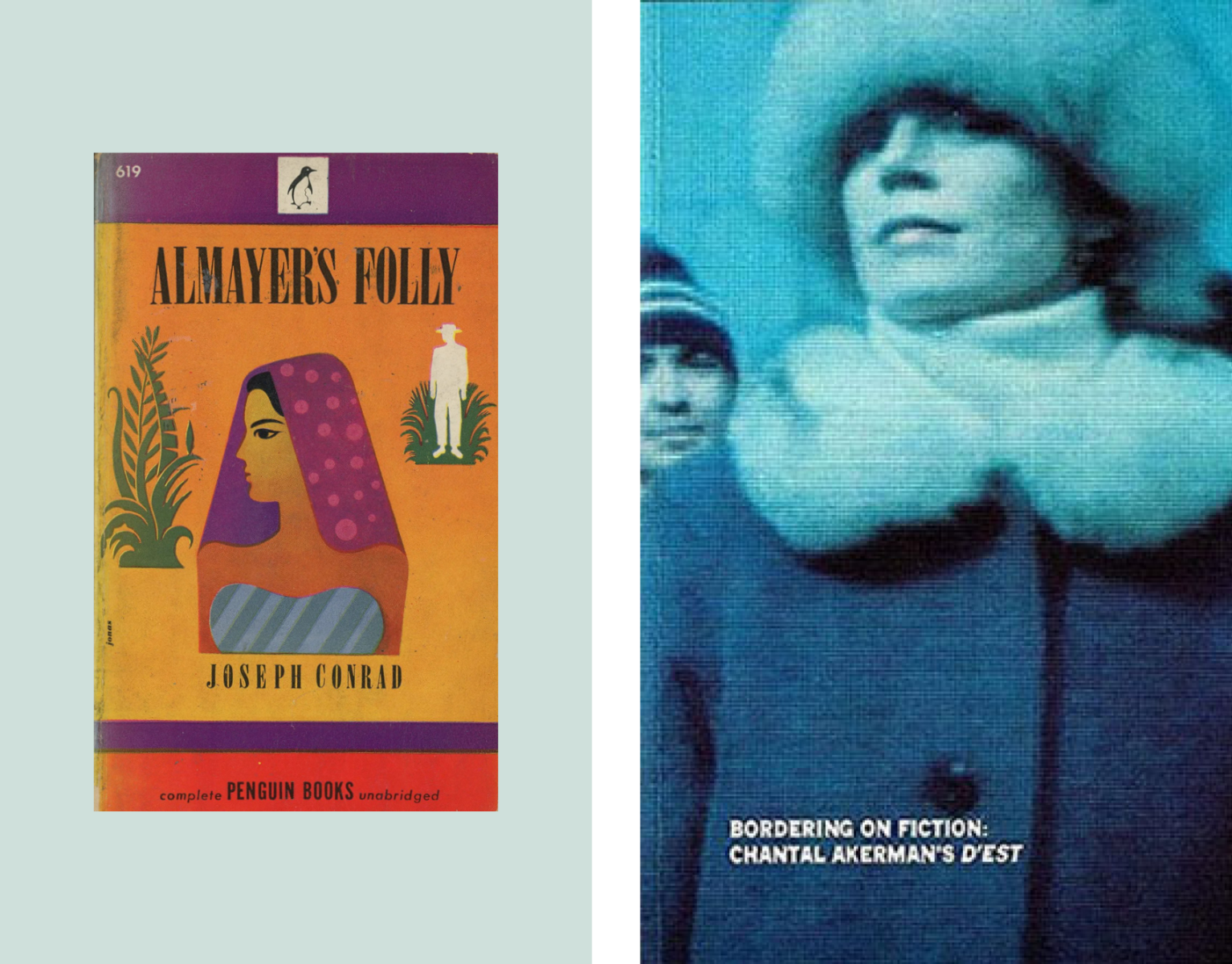

From left: Almayer’s Folly by Joseph Conrad, Bordering on Fiction: Chantal Akerman’s “D'Est” by Chantal Akerman

As I would discover, she didn’t take to simple labeling. Call her a feminist, queer or Jewish filmmaker at your peril. I asked her about being a queer filmmaker and received short shrift. “People can talk about it, but I’m not interested in talking about it. I do my thing,” she balked. “How many lesbians do you know? One lesbian is different, just like one Indian is different, to another. But [the media] have to make labels. I don’t call myself a lesbian filmmaker; I call myself a filmmaker. Eventually, I said, ‘I love girls.’” She then added, “But I also love boys. I’m not so strict, and it doesn’t interest me. I’m more like Judith Butler, what she writes in Gender Trouble. That’s interesting. Because what is a man? What is a woman? What is a lesbian, and what is not a lesbian? In fact, all these notions are so reducing. So please don’t call me a lesbian filmmaker, or I’ll kill you! I’m a filmmaker, and it so happens that most of the time I love girls.”

She was also someone who did not stand still creatively. Her cinematic efforts became broader and less formal with time. With each work, she said, she became more liberated in her directing and less reliant on precision or manufacturing the ideal frame. Her aesthetic and directing style had completely changed by the time of her final fiction film. “I now spend as little time as possible planning shots,” she said. “Because you kill the actors, and you kill the crew. And with Almayer’s Folly, for the first time, I made a film that was not shot in a very contrived way. Usually on set, I would say to the actors, ‘We stop here,’ and to the crew, ‘You plant the camera there,’ but I think it would have killed this film, so I gave a lot of freedom. I would not know when Stanislas Merhar would stop, so each take was an adventure; it felt like I was acting with him. Otherwise, shooting can be so boring, but here each time was an invention.”

La paresse, dir. Chantal Akerman, 1986

Akerman had no children. However, she told me that when shooting Almayer’s Folly in Southeast Asia, “I wanted to adopt a child, and she wanted to come with me to New York, but she could not because of all the rules and regulations. I wanted her to go to a good school, so I ended up sending money to her.” Akerman mentioned her desire to adopt as part of an anecdote about observing the behavior of people who had suffered. “[The child’s mother] told the translator what was important was that I had a good heart. I thought it related to suffering, because these people had been through many problems.” Arguably, this is the essence of so many of Akerman’s memorable characters: They were people who, because they had suffered, were searching for people with good hearts.

Our final exchange seems, in hindsight, slightly morbid. The standard last question of what is coming next was met with the stiff response, “Let’s not talk about my next project. I have no idea yet about another film. I have lots of exhibitions. They want me to rush all over the world to support this film, but I will try to do as little as possible. Otherwise, it takes all your life.”