The Intuitionist: Claire Atherton

By Yonca Talu

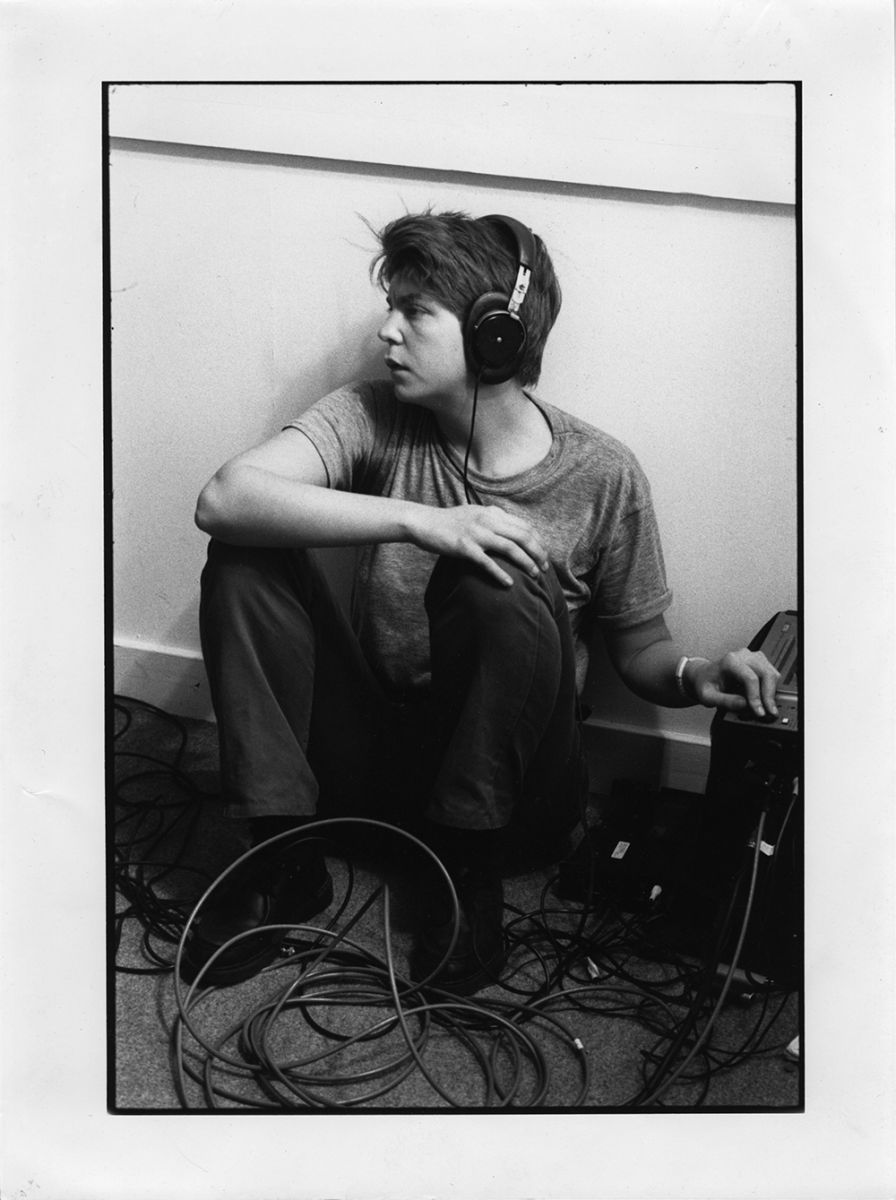

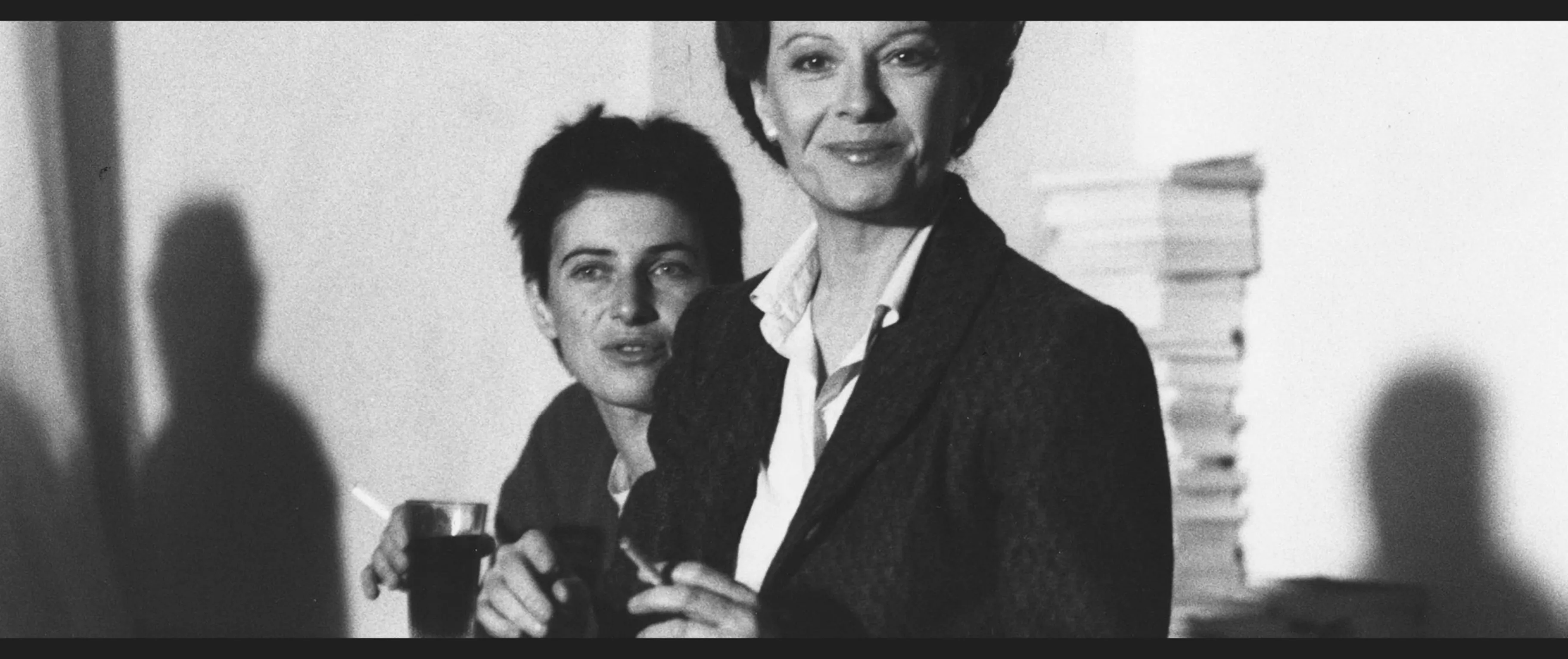

Claire Atherton in New York, July 1988 (photo by Chantal Akerman)

The Intuitionist

EDITOR CLAIRE ATHERTON’S ENDURING SYMBIOSIS WITH CHANTAL AKERMAN

By Yonca Talu

October 4, 2023

Few cinematic partnerships have been as symbiotic and fruitful as that of trailblazing Belgian filmmaker Chantal Akerman and her editor Claire Atherton. They met in 1984 through Delphine Seyrig—the star of Akerman’s modernist masterpiece Jeanne Dielman, 23, quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles (1975)—and collaborated extensively until the director’s death in 2015. Spanning genres and mediums, Akerman’s works edited by Atherton include the Eastern European travelogue From the East (1993), which they also expanded into the first of many video installations; the U.S.-set documentaries South (1999) and From the Other Side (2002); and fiction films as diverse as the romantic comedy A Couch in New York (1996) and Almayer’s Folly (2011), an adaptation of Joseph Conrad’s tragic novel. A firm believer in trusting the process, Atherton relies on feeling and intuition to navigate the editing of a film rather than following preconceived ideas about its structure and meaning. Drawing on her Chinese studies and background in classical music, she weaves images and sounds into rich tapestries of rhythms, textures, moods and sensations that viscerally engage the audience and defy traditional storytelling. I sat down with the influential editor at the Paris studio of one of her regular collaborators, artist and filmmaker Éric Baudelaire, to discuss her childhood in America and France, highlights of her work with Akerman and how she developed her editing philosophy.

Claire Atherton at the Simone de Beauvoir Audiovisual Center, 1984

You were born in San Francisco. Did you also grow up there?

I was born in San Francisco and spent my early childhood in New York. We moved to Paris in 1968, when I was five, and the story goes that our plane couldn’t land in Paris because of the May ’68 events, so we landed in the south of France. I returned to New York many times after moving to Paris, but I only returned to San Francisco years later, in 1995. Chantal and I went there to exhibit her installation D’Est, au bord de la fiction [From the East: Bordering on Fiction], and I remember feeling immediately at home, like there was something very familiar in the air.

Do you have any memories of your childhood in the U.S.? I ask because the ’60s were obviously a significant decade in American history.

I can’t say I have specific memories; they’re more like dreams—part true, part imagined. I’ve always loved Janis Joplin, who emerged in those years, though I’m positive I didn’t listen to her songs as a toddler in my room in San Francisco or New York. [Laughs] But I was definitely immersed in the political atmosphere of the time because my father, John, who taught at the University of California, Berkeley, was very active against the Vietnam War. In fact, when I saw the opening sequence of Antonioni’s Zabriskie Point [which depicts a student-activist meeting in late-’60s L.A.], I had the impression of seeing my dad.

Your mother, Ioana Wieder, was also an activist and a member of the ’70s feminist film collective Les Insoumuses with Delphine Seyrig, Carole Roussopoulos and Nadja Ringart.

Yes. I helped Les Insoumuses a lot as a teenager. I did technical tasks on their films, like operating videotape recorders. I’ve always been suspicious of theory, which is why I wanted to get acquainted with machines early on.

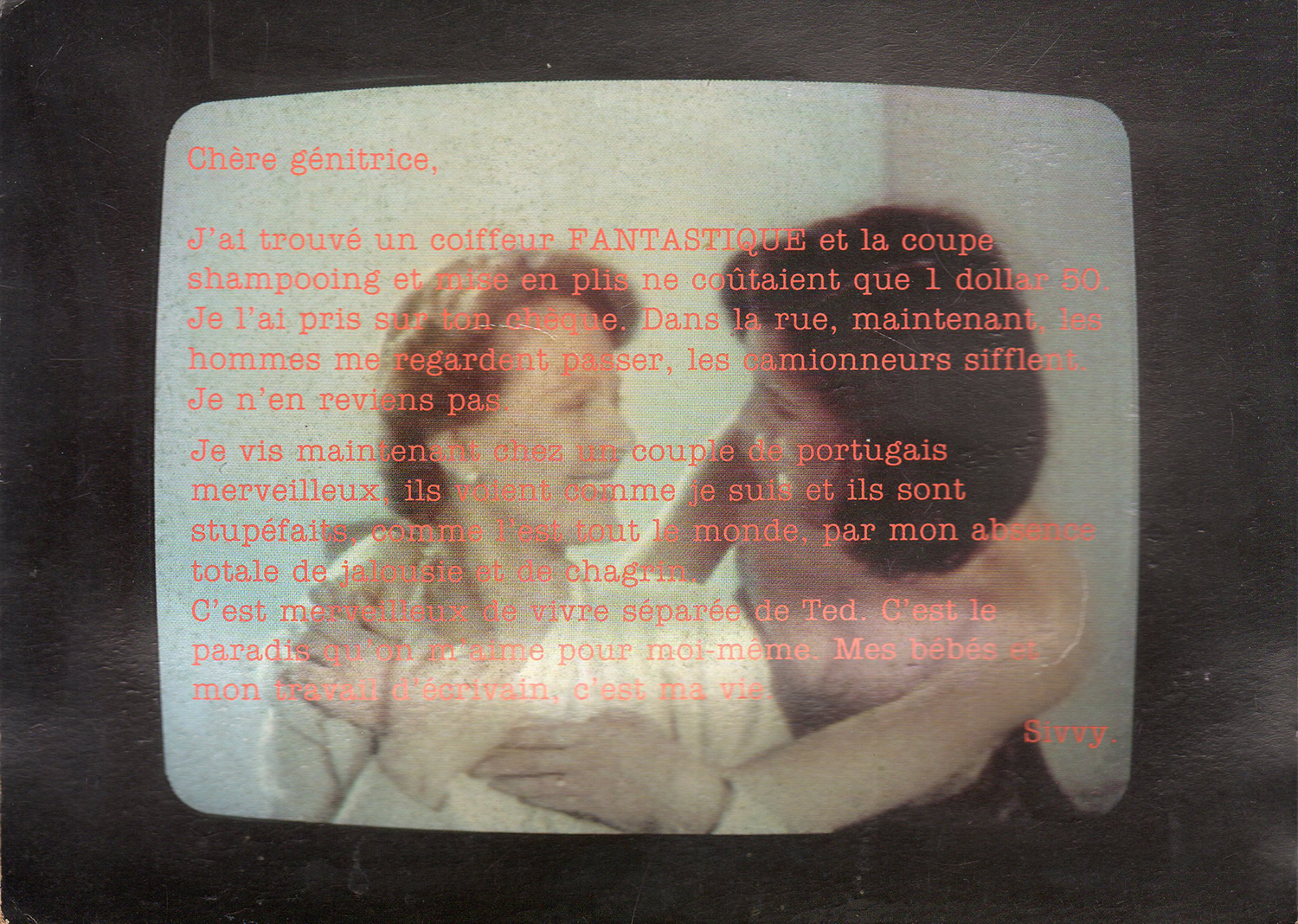

Letters Home invitation card, December 1987

You wanted to be hands-on.

Exactly. Growing up, I was much more comfortable with images than with words. I liked drawing and looking at an art magazine to which I subscribed. Sometimes when the other kids were playing outside, I would stay in my room and sort my magazine copies into binders. What appealed to me even then was the act of assembling and organizing images.

That eventually led to my interest in Chinese, which I started learning in high school and studied in college. I was really attracted to the fact that in Chinese writing you draw words and associate images. And I loved that by associating images, you could create not one but multiple layers of meaning. Later I became passionate about Chinese painting and poetry. There was a painter from the Tang dynasty era, Wang Wei, who argued that it was impossible to reproduce all the colors of nature. So he proposed to paint landscapes in black and white and leave it to the viewer to imagine their nuances. This was eye-opening to me; even talking about it now fills me with emotion.

You’ve spoken before about the fact that Chinese philosophy and civilization have influenced the way you edit.

That’s something I discovered in retrospect, when I was asked at a film festival what led me to editing. It’s a question I’d never asked myself, and I realized that everything I had learned and loved about Chinese philosophy and civilization was present in my editing practice and collaboration with Chantal.

There’s a notion in Chinese thought that means a lot to me—that of emptiness. In Taoism, emptiness is a site of constant transformation, a place where vital breaths meet and from which meaning springs. As an editor, I try to create a similar space in which every viewer can forge their own connections with the film and experience it as they please.

Another link between my practice and the Chinese art of living is my need to establish a certain harmony, or ‘‘feng shui,’’ in the editing room. Editing joins together two poles of the human being: organization and intuition. It’s about focusing on practical things like sorting out the footage, and grounding yourself in reality so that your mind can wander freely and welcome the unexpected. That’s how Chantal used to work, too. She was quite a lucid, quick-witted person. But she also had a very intuitive and open way of being in the world.

It was Delphine Seyrig who introduced you to Chantal Akerman. Do you think she intuited that you two would be compatible collaborators?

Possibly. Delphine was someone who had a huge impact on me. We worked together when I interned as a video technician at the Simone de Beauvoir Audiovisual Center [a feminist film archive created by Seyrig, Roussopoulos and Wieder], and I was very influenced by her subversiveness and risk-taking.

In 1984, Delphine and her niece Coralie starred in a French production of Letters Home [a play by Rose Leiman Goldemberg based on the epistolary exchange between Sylvia Plath and her mother, Aurelia]. Delphine called me one Sunday morning and asked if I could pick up Chantal and assist her in recording that afternoon’s performance for a TV channel, which I happily agreed to do. When we got to the theater, I set up the camera so that Chantal could film and I could take care of the focus. But a few minutes into the show, she said, ‘‘I’m not seated comfortably. You go ahead and film.’’ So I took over the camera and started filming. I didn’t even have time to be nervous or wonder if there was anything at stake for me. I just did it, and whenever I felt like panning or zooming in on the two actresses, Chantal was telling me to do the same. There was an incredible synergy between us.

At the end of the show, Chantal went up to Delphine and said, ‘‘Who is this girl? I’d like to work with her.’’ It was a very moving moment—the beginning of an essential and fascinating story in my life. But I also love what it says about Chantal. While most people would have asked to see my résumé, she met me in the present and wanted to keep working with me without knowing anything about my background.

That must have set the stage for the rest of your collaboration, which wasn’t limited to editing.

Yes. I edited a lot of Chantal’s films, but we also made installations and sometimes she even liked having me around when she was writing. In the late ’80s, I both shot and edited a few short movies she directed, including a lost one called Marguerite Paradis. I also worked as a camera operator on Histoires d’Amérique [1989] in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, which was a wasteland at the time and a place Chantal loved in New York.

Chantal Akerman and Delphine Seyrig shooting Letters Home, 1984 (photo by Catherine Deudon)

What was Chantal Akerman like on set? Did she work any differently than in the editing room?

I don’t think so. What characterized Chantal on every project we did together was the creative zeal with which she undertook it. It was almost like she was struck by a fever. There’s a line I adore in her film Tomorrow We Move [2004]. When asked who she’s in love with, the protagonist replies, ‘‘With no one in particular; it’s a general feeling.’’ That was also true of Chantal herself, whose presence and creative energy possessed a childlike quality. Children are interested in everything; they have an intense and uninhibited relationship with the world. Chantal was similar in that she overflowed with curiosity as a filmmaker and didn’t emphasize certain decisions over others. Every element in the film mattered. For example, in The Meetings of Anna [1978], the sound of the heroine’s high heels was as essential and meaningful to Chantal as the dialogue and events.

The first Chantal Akerman feature you edited was Letters Home [1986], a film based on the play that led to your meeting. How did that project come about?

After we recorded that performance together, Chantal took a liking to video and became interested in making a film in that medium based on Letters Home. The idea was to go onstage with the camera and visually break down the play. I collaborated with Chantal on the shot list but wasn’t present on the shoot itself, which took place in a suburban theater over two or three weeks.

“In Taoism, emptiness is a site of constant transformation, a place where vital breaths meet and from which meaning springs. As an editor, I try to create a similar space…”

Letters Home was edited in a now-obsolete video format called U-matic, in which every cut was more or less irreversible. Was that a daunting experience for you as a young editor?

No, it was as organic an experience as my meeting with Chantal. The way that U-matic worked was that you had two devices: a player on which you selected the edit points and a recorder on which you copied them. That’s how you lined up the shots, and if you wanted to go back and change a cut, you basically had to redo everything that followed or go through additional steps that messed up the resolution. So it was best to just move on, which was a challenging but also stimulating process for Chantal and me because we liked working without a safety net.

There’s another aspect of how we edited Letters Home that still astounds me today: We’d watch the takes and whenever one of them felt right, we would edit it in without watching the others. It seemed pointless to look for the perfect take. Instead we embraced imperfection and trusted our first gesture, which is something I value a lot as an editor and try to impart to my students and the directors I work with for the first time.

Do you always hold on to that first editing gesture?

I might adjust or refine it, but there’s always an interesting quality to it. When I start editing, I need to try things in a state of unconsciousness. If the director sits there questioning what I’m doing and why, it causes me to question myself too and breaks my momentum. I prefer following my impulse and understanding later, and I’m not afraid of getting lost in the process.

That has to do with the fact that I’m terrible at directions. [Laughs] About 10 years ago, I was on the graduation jury at La Fémis. At some point I went to the bathroom and exited through the wrong door. I couldn’t find my way back to the jury and had to ask for help. I was embarrassed and ashamed, but then I realized that not having a sense of direction and getting lost actually helped me edit. So now I’m quite proud of it! Likewise, I have trouble remembering the order of events in a screenplay. Sometimes when I’m editing, I don’t know which scene comes where. That allows me to keep discovering the story as I go and prevents me from having a linear relationship with the film.

Jeanne Dielman, 23, quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles, dir. Chantal Akerman, 1975

You like to compare editing to composing music.

I do. I also compare it to sculpture because I like the image of modeling a film with one’s hands; so did Chantal. In my youth, I played the alto recorder and transverse flute in baroque music ensembles. I loved Bach, especially his cantatas like the Mass in B Minor. I also fell in love with Philip Glass’s music after seeing Einstein on the Beach at the 1976 Avignon Festival. One of the things I took away from those experiences is an understanding of rhythm. Rhythm is often confused with pacing, but what it really refers to is the web of echoes and resonances that runs through a work of art. My aim as an editor is to create those resonances in a film by pulling and weaving together all the threads that make up cinematic form, including images, sounds, colors, lights, substances, geometric elements, contrasts, etc. I treat the film as though it had multiple voices, like a musical composition. For example, a very slow tracking shot of a quickly moving crowd would be a moment in which one voice is calm while the other is agitated. I may follow this with an image that marks a pause, a kind of fermata, before taking off again. That’s how I construct a film—by shaping its rhythm.

Did you follow a similar process in your installation work with Chantal Akerman?

Yes, but installations also propelled us into a new realm. It was as if we’d been editing on a timeline until then and were introduced to spatial editing. Suddenly we could juxtapose images and sounds in space and have them echo each other in real time, which sparked so many creative possibilities.

How did you and Chantal Akerman go about creating her first and best-known installation, D’Est, au bord de la fiction, which builds on her 1993 film From the East and features as many as 25 monitors? Did you struggle with logistics?

A little bit, but we took it step by step and enjoyed discovering as we went along. First we got From the East transferred to video and made a copy of it. Then we played those tapes on two monitors that were out of sync to see if anything emerged. There were juxtapositions that appealed to us, but they either mirrored or opposed each other and we wanted to transcend that binary. So we set up a third monitor and created eight triptychs using four-minute segments of the film.

We conceived the installation as having two rooms: one in which From the East would screen in 16mm and another in which the triptychs would unfold across 24 monitors. But then we felt like we were missing something important. A film has a beginning, a middle and an end and builds up tension over time, whereas an installation runs in a continuous loop. The only ending is for visitors to leave or retrace their steps, which didn’t suit us because it lacked a sense of tension. So we decided to build a third room that would extend and culminate the installation.

At that point we felt the need to put into words what some of From the East’s images had evoked to us all along and which we hadn’t dared acknowledge [i.e., images of mass deportation]. We struggled a lot but eventually came up with what became the text of the installation’s 25th and final monitor. We recorded Chantal’s voice reading it, then searched for an image in the film that could fit in with it. The only one that did was a nocturnal tracking shot of a road on which we zoomed in to the point of abstraction.

Almayer's Folly, dir. Chantal Akerman, 2011

Chantal Akerman’s last film, No Home Movie [2015], which documents the final years of her mother’s life, is another example of how complementary her cinema and installation work could be.

Yes. Chantal and I were supposed to meet to edit her installation De la mèr(e) au désert [From the Sea/Mother to the Desert; 2014], which she’d shot in Israel. In the meantime her mother, Natalia, passed away, and when I went to her place to start working on the installation, Chantal said, ‘‘I want us to take a look at all the footage I filmed of my mom these past two years.’’ There were images everywhere, even on her cell phone, so we spent a lot of time just getting them onto the computer. Then we watched them and made a four to five-hour assembly of moments that touched us, but I don’t think we were in an editing mindset. We were merely cherishing the love between Chantal and Natalia and trying to keep her with us as long as we could.

Meanwhile we continued to work on the installation and gradually realized that the two materials would merge. And it’s when we put the tree [battered by the desert wind] as the opening shot that we finally felt like a film was possible. It’s as if we needed the frenzy and rage of that tree to be able to reveal Chantal’s mother in all her gentleness in her Brussels apartment.

Later we tried to shorten the tree shot [which lasts about four minutes]. We screened the film to see if it worked, but after a while Chantal said, ‘‘Stop, I’m not feeling it.’’ I was relieved because I hadn’t felt shaken enough by the tree either. Of course, we didn’t conceptualize any of that. If one starts pondering how to shake up the audience, everything gets ruined. Our process was the exact opposite—we began with little things, with feelings and sensations, and constructed meaning out of those.

Translated from French by Yonca Talu