Cloak and Jagger

By Tim Blanks

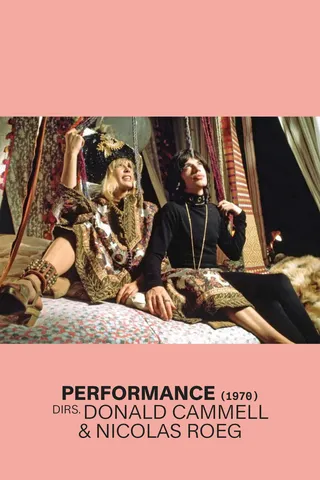

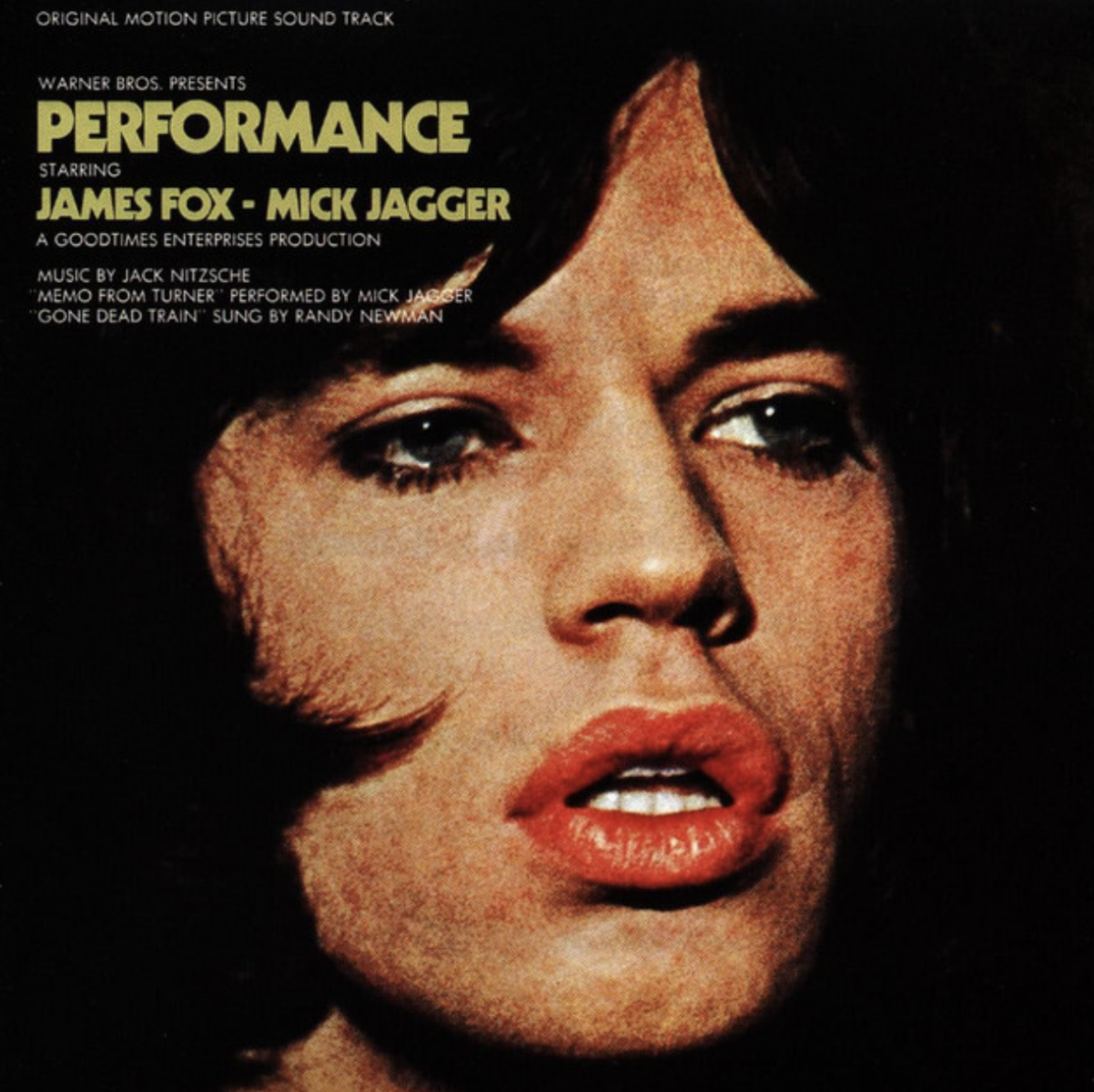

Performance, dirs. Donald Cammell and Nicolas Roeg, 1970

Cloak and Jagger

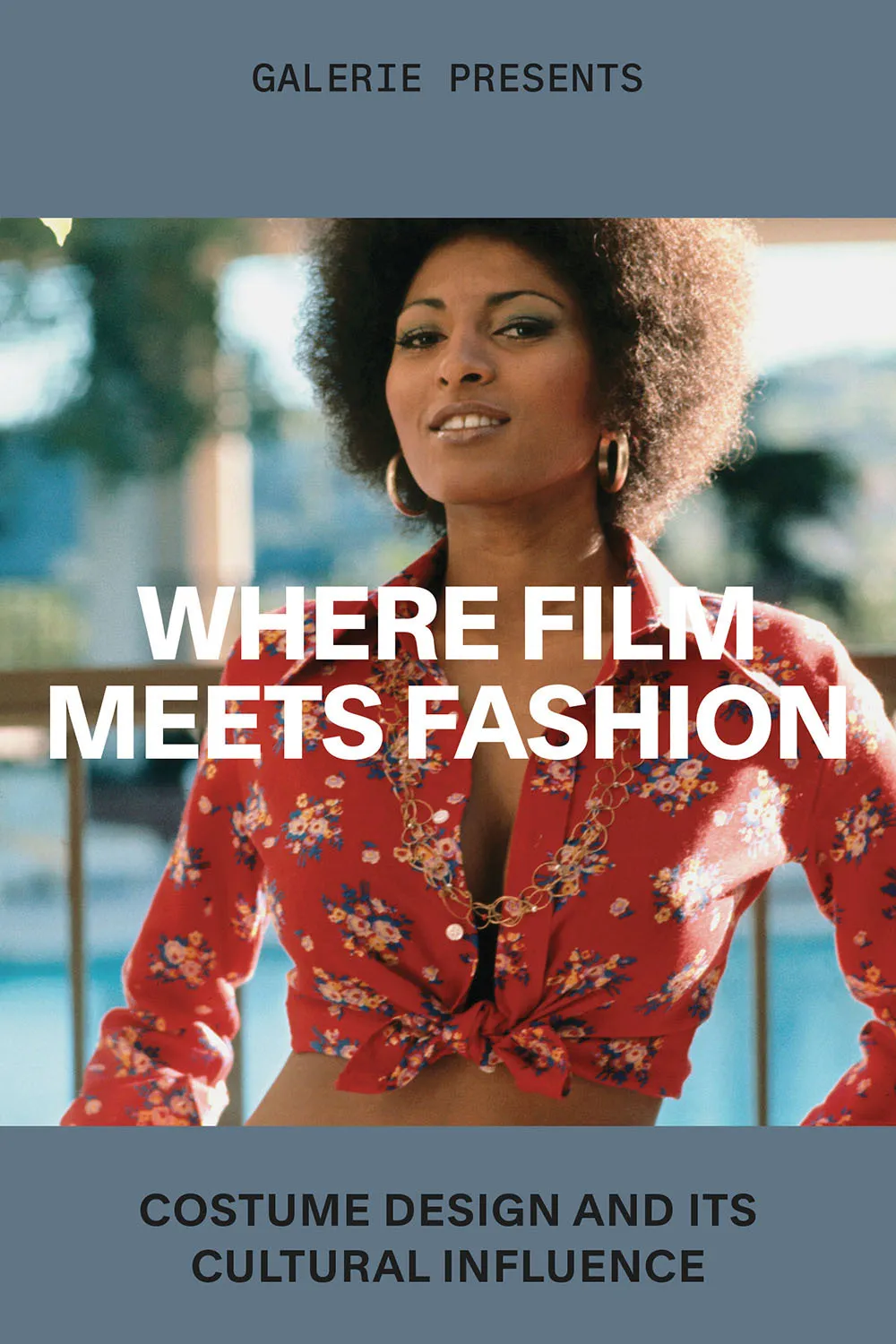

The fashion revolution in the definitive end-of-1960s cult film Performance

By Tim Blanks

September 20, 2024

Quentin Tarantino called Performance “one of the best rock movies of all time.” A fine encomium, bar the fact that it isn’t a “rock” movie per se. But, by Tarantino’s line of reasoning, you could also dub the film one of the greatest fashion movies ever made, without it actually being about “fashion.” It’s a challenge to think of another piece of celluloid that so convincingly depicts the extravagant, erotic, transformative power of clothes as the fundament of identity, gender and sexuality. All of which makes Performance, a film that first saw daylight in 1970, a dazzling harbinger of our own tumultuous times.

![]()

![]()

Anita Pallenberg in Performance

Directors Donald Cammell and Nicolas Roeg began production on the film in January 1968. Warner Bros. probably thought they were getting some kind of groovy pop paean, given that the marquee name attached to the project was none other than Swinging London’s crown prince, Mick Jagger. But what they actually got was the story of Chas (James Fox), an East End gangster on the lam from murderous colleagues, who hides out in the West London home of Turner, a reclusive rock god (that would be Jagger), and is transmogrified under the sexual and chemical influence of the singer’s exotic ménage. Hollywood suits were, unsurprisingly, so horrified by previews that it was two years before a corporate reedit finally limped into American theaters.

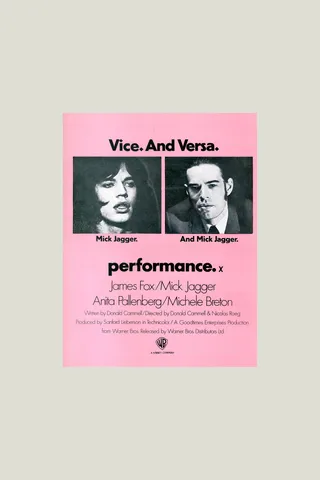

Those lost two years consolidated for posterity Performance’s status as a work of peculiar foresight. A year and a half after Cammell and Roeg began shooting, the idealistic pipe dream of the ’60s peaked at Woodstock, just a week after Charles Manson and his Family butchered Sharon Tate and her friends in L.A.’s Benedict Canyon. That these perverse polar opposites could coexist was a macabre irony that seemed appropriate to the subject and tone of Performance. As the film’s poster advertised, “Vice. And Versa.” There was another ironic twist in Jagger’s metamorphosis, during the film’s two-year gestation, from Crown Prince of Pop Culture to Beelzebub of Rock, courtesy of the Rolling Stones’ disastrous—and in the case of one concertgoer, fatal—appearance at the Altamont Speedway Free Festival in December 1969. The reservations that Warner Bros. had about the film’s commercial prospects weren’t entirely off base: On its eventual U.S. release in August 1970, it flickered briefly before disappearing.

A decade later, the studio released Performance on home video. By then it had found a dedicated fan base of artists, musicians, filmmakers and fashion designers. The intervening decade amplified an essential, primal quality of the film that its original ardent fans already understood. In 2003, the British Film Institute financed a new print of the film, which went into DVD a few years later. No matter the decade, Performance was so entirely sui generis in its bold, brash style that it transcended temporal context, which freed it to influence generation after generation. And that is how Performance garnered one of the most intense cult fan clubs in celluloid history. It has had a seismic effect on fashion, its look, attitude and polymorphous perversity seeming to hold particularly seductive sway over many of the designers, stylists and photographers who are celebrated for their own grip on the zeitgeist. In their all-consuming ’70s pomp, the Rolling Stones felt like Performance’s decadence, writ large and irresistable. There is something specific about Turner’s rich, bohemian world as a place where some of us wanted to be.

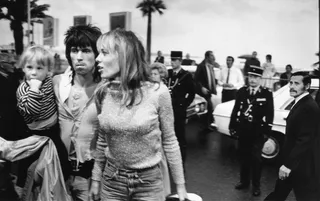

From left: Bianca Jagger and Mick Jagger at the Newcastle Central Station, 1971; Marlon Richards, Keith Richards and Anita Pallenberg at the Cannes Film Festival, 1971; Richards and Pallenberg in London, 1973; Anita Pallenberg and Keith Richards at home in Chelsea, 1970

“And that is how Performance garnered one of the most intense cult fan clubs in celluloid history.”

I know I did. I was 15 when I first saw Performance in 1970, on the day it arrived in my local bijou in Auckland, New Zealand. I sat, glued to my seat, confused but awestruck, through four consecutive screenings. More than five decades and a hundred or so viewings later, I feel confident in saying that the film is still a total mindfuck. The spell it induced wasn’t simply its premise: a gangster movie grafted on to a titillating “sex and drugs and rock’n’roll” template, a fish-out-of-water storyline pushed to surreal extremes. Rather, the filmmakers and their performers mutated that story into a profound and timeless meditation on identity, enhanced by a radically fragmented cinematic style that serves as a visual correlative of egos shattered and reshaped. Chas arrives in Turner’s shabby house in Powis Square, in pre-gentrified Notting Hill, bloodied and bruised but sharply suited and booted like the ultra-masc gangster he is. Turner is androgynously engaged, either naked in a bathtub with his concubines Pherber and Lucy, draped in diaphanous caftans, or swathed in silk and velvet. There’s a lot of languorous lip-painting. Worlds collide as posh boy Fox and rock star Jagger surrender completely to their characters. At one point, Turner provocatively declares that the only performance “that makes it all the way is the one that achieves madness.” In the course of the film, they do indeed achieve a kind of role-reversing madness. By the film’s contentious climax, Chas has shed his sleek mobster suits, taken on Turner’s silks and velvets, and been consumed by his persona. Again: Vice. And Versa.

Designer Anna Sui shares my obsession, so we had to talk. In the mid-’70s, she had recently moved from her native Detroit to New York when she encountered Performance in one of the city’s small repertory cinemas. Thoroughly under its influence, she set out to transform her railroad apartment in the East 50s into Turner’s Notting Hill lair—the same black walls, the draped Indian fabrics, the curtains of lace, the Persian kilims and pillows. She even blacked out the windows to guarantee the requisite decadent gloom. Performance has stayed with her for the rest of her career, and, for fashion at large, whenever haute bohemianism becomes a thing, Performance is there—in Martine Sitbon, in Dries Van Noten, in Isabel Marant, in Alessandro Michele’s Gucci. The influence seeps rather than sledgehammers.

![]()

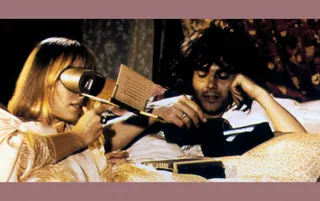

Anita Pallenberg and James Fox in Performance

![]()

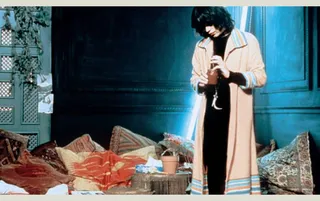

Mick Jagger in Performance

Overwhelming credit for that impact is due to Anita Pallenberg, the German-Italian actress who played Pherber, Turner’s Teutonic amanuensis and, in real life at the time, Keith Richards’s girlfriend. In the film, she shares Jagger with a French gamine played by Michèle Breton. According to legend, the film’s sex scenes were real, which makes it easy to imagine the friction that caused chez Richards. With the passage of time, Pallenberg came to personify Performance, almost like a character unwillingly plucked out of the film, in every appearance she made until her death in 2017. “You never saw anybody so beautiful,” Sui rhapsodizes. “Her first appearance in the fox fur coat? I’d never seen or heard anybody like that.” Pallenberg endured as a reference point for equally influential style mavens such as Kate Moss and Steven Meisel (who photographed Pallenberg for a Calvin Klein denim campaign in 1995).

Pallenberg had the same effect on everyone, as is gloriously elucidated in Catching Fire: The Story of Anita Pallenberg, the recent documentary produced by her son, Marlon. She was a one-woman fashion revolution with her magpie instincts for marrying men’s and womenswear, vintage and high fashion, sophistication and barbarism. Brian Jones was her first Stone. After he’d done her wrong, Keith Richards rescued her. As a thank-you, she transformed him. Her—her clothes—made him the prototype for a thousand rock stars since. Pre-Anita, Keith was a guitarist in a band. Post-A, he was a style icon. And it was her Biba blouses or ruffled shirts from Granny Takes a Trip that he wore, her tapestry pants or python jeans with hip-slung belts that he shoehorned himself into.

From left: Dries Van Noten Fall 2017 Ready-to-Wear; Biba Spring 2007 Ready-to-Wear; Isabel Marant Fall 2024 Ready-to-Wear

She had a similar impact on Jagger after Performance. Emma Porteous has the credit for the film’s costume design, but the clothes that Jagger wears as Turner are not a simple simulacrum of what the world thought it already knew about the Stones front man. They seem more like a distillation of Pallenberg’s own wardrobe. And these vestments insinuated their way into his subsequent onstage wardrobe: the leggings, the floaty blouses, the silky scarves and amulets, the leather cuffs and neck bands, tokens of kink. Jagger at Altamont is Turner incarnate.

But Turner’s world is only one part of the film. In Cammell’s original script, Performance was equally taken with Chas’s criminal world. Swinging London was fascinated by the same intersection of crime and show business that ensnared Hollywood, but even Bugsy Siegel never had the sinister allure of the East End’s Kray Brothers. In his iconic 1965 Box of Pin-Ups, photographer David Bailey’s definitive visual record of the era, the Krays are starkly glamorized alongside John Lennon and Paul McCartney and the Stones and Shrimpton and all the other faces who made London the mecca of cool. “America didn’t have the Krays, that ‘coolness’ of criminality,” says Sui.

![]()

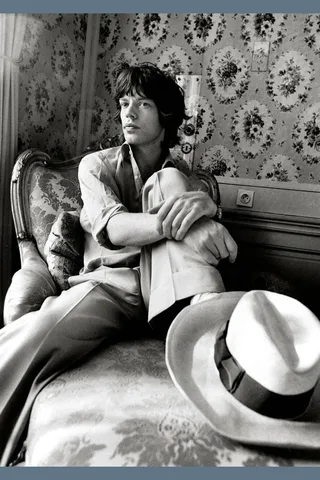

Mick Jagger in his hotel room in Vienna, 1973

![]()

Original poster for Performance

The same note of cool perversity struck British fashion designer Bella Freud the first time she saw Performance in her susceptible teen years. The studied fastidiousness of Chas’s look has echoed through the sartorial edge of her collections over the decades. (Pallenberg herself favored Freud’s sharply tailored pants.) There is a telling scene at the beginning of the film, when Chas ignores his girlfriend while choosing his cufflinks for the day. It flashes forward a decade to the persnickety dandyism of Richard Gere in Paul Schrader’s American Gigolo. What makes a man? The choice of cuff links? The capacity for mindless violence? The performance of masculinity cuts to the quick of the film. When Chas, well under the influence of mind-altering substances, is challenged by Pherber, his protestations about being a man sound appropriately feeble. And they’re a reminder of the ambiguities that unhinge our present moment.

If Anita Pallenberg released the id in the Rolling Stones and, by extension, into pop culture at large, perhaps the most remarkable sequence in Performance is a musical “fantasy” (for want of a better word) sequence in which Jagger, in slicked-back, suited-up gangster garb, performs “Memo from Turner,” the best song the Rolling Stones never recorded. If the studio was hoping for a Stones soundtrack, it’s the sole Jagger/Richards credit on the actual soundtrack that composer Jack Nitzsche produced, which is as remarkably prescient as the film itself, embracing electronica and rap decades before they became things. The song’s three minutes of sinister perfection similarly anticipates the video revolution of MTV. And Jagger’s triumphantly sneering delivery—which manages to be both sexually aggressive and sexually ambiguous—also foreshadows the evolution in his own live persona. In other words, another consummate performance.

“That film marked the end for me,” Anita Pallenberg has always maintained. “The end of the beautiful ’60s—love and all that.” But Performance was more the beginning of something for professed fans like Quentin Tarantino, Martin Scorsese and Jonathan Glazer, and all the fashion designers who tip their cap without maybe even realizing it. The house in Powis Square was truly a Pandora’s box.

Performance soundtrack