Seventies Reverb

By Ellie Pithers

![]()

Gucci Spring 2023

Seventies Reverb

Then as now, sartorial trends reflect sociopolitical realities

By Ellie Pithers

July 1, 2023

There’s a scene halfway through Robert Altman’s 3 Women (1977) that neatly sums up the sartorial doublethink the 1970s—a once-derided, now revered decade—require today. Having spent much of the film bragging about her cooking and her recipe for tuna melts, Millie Lammoreaux (Shelley Duvall) is assembling dessert for a soiree at her egg-yolk yellow apartment in the California desert, squirting cream from a can in swirls on shop-bought tarts filled with canned chocolate pudding. Affecting the sophisticated hostess, she pronounces, “I’m famous for my dinner parties.” Never mind that they consist of processed food and Pringles.

![]()

Shelley Duvall and Janice Rule in 3 Women, dir. Robert Altman, 1977

A magazine-obsessed young woman who revels in tokens of idealized 1970s womanhood—the contraceptive pill, “Lemon Satin” wine, the concertedly sunny color yellow—Millie is nevertheless the kind of girl who accidentally shuts her dress in the door of her Ford Pinto. The sun-bleached and frequently surrealist world of the film—one Altman summoned in the aftermath of the failed dreams of the 1960s, amid rising inflation and crime in the U.S.—is built on delusion that ultimately infects the audience. No one turns up to Millie’s dinner party and eats the artificial food, but it doesn’t seem to matter. For viewers, the lingering image is of Duvall admiring herself in the mirror, wearing a halter-neck cheesecloth dress in her favorite daffodil-yellow shade, a little prim from the front but cut daringly low in the back. With her hair set in a luxuriant Breck Girl wave, corsage of fake yellow flowers on her arm, Millie is the very embodiment of wide-eyed ’70s self-expression, determined to make her way in life.

Nearly 50 years on, we’re more hung up on the 1970s than ever, having repositioned the decade from a world of unflattering sideburns to one of sensual decadence. In design, louche Mario Bellini sectional sofas are everywhere you look on Instagram, their formerly seedy squishiness now semaphoring good taste. In music, disco is enjoying an unprecedented revival (blame ABBA, their avatars, and pandemic kitchen dance-offs). Meanwhile, psychedelics are being hailed as the next big trend for mental health. Set against an eerily familiar backdrop of an oil crisis, runaway inflation, popular protest and a new cold war, and the ’70s revival feels an apt cultural mirror to reflect current world events.

Mario Bellini sectional sofa

Mario Bellini sectional sofa

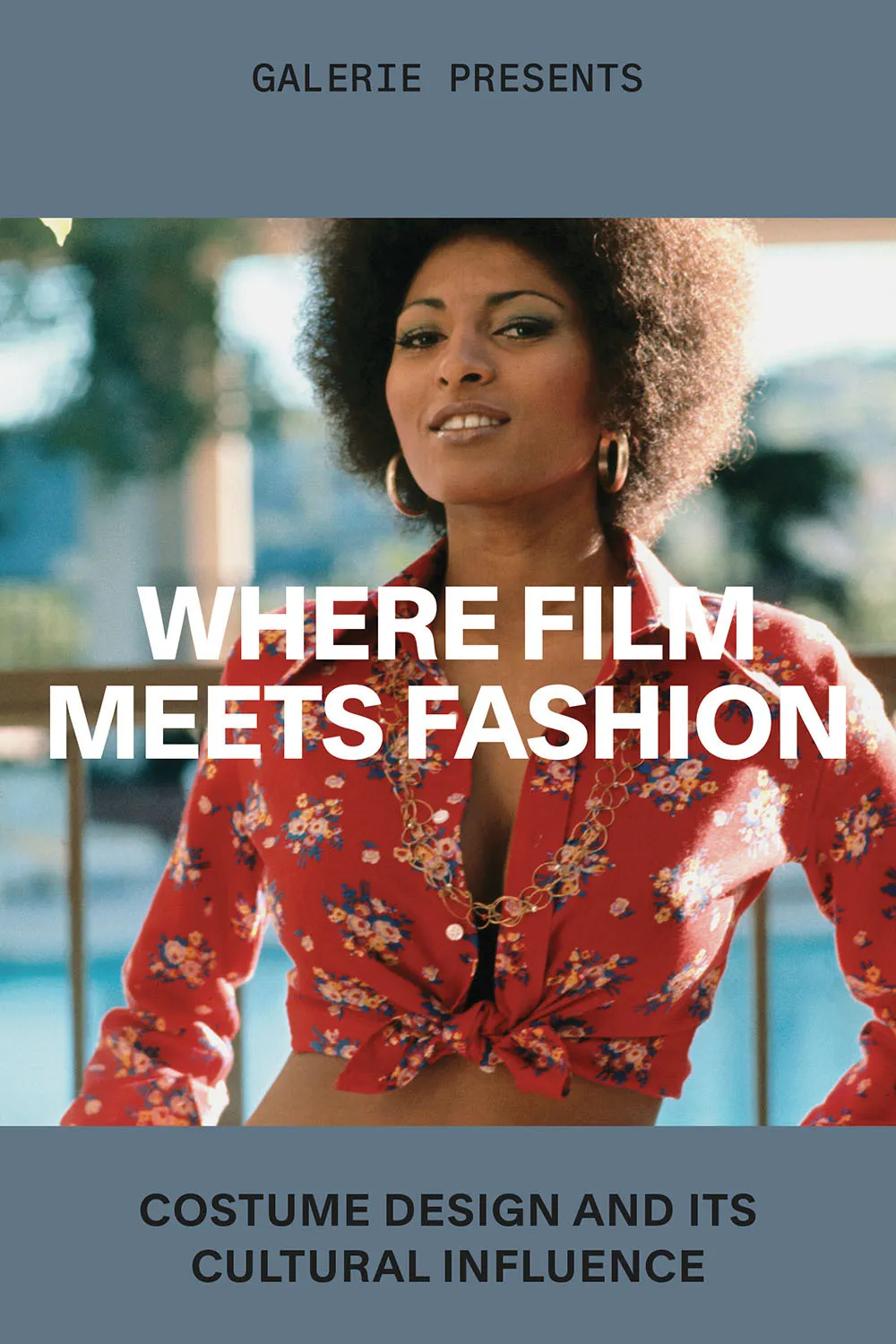

Nowhere is this more evident than in fashion, where one brand can be credited with kicking off the decade’s rehabilitation: Gucci. From 2015 up until his recent departure, Alessandro Michele, as the brand’s creative director, reshaped the Italian juggernaut’s image with the decade as his lodestar, filling his catwalks with shaggy-haired, androgynous models wearing colorful suits, wafty dresses, heeled horsebit loafers and tinted sunglasses. “The period of greatest liberation, which I lived through when I was a child, was the ’70s, which were really the golden years of the brand I work for, and I keep going back to them because, for me personally, they were the real seeds of change,” the designer explained in a statement accompanying Gucci’s resort 2021 show. The Rodarte sisters, Kate and Laura Mulleavy, are in agreement, often basing collections on their late-1970s childhood in suburban California, inspired by wood paneling and early Star Wars movies. So too Isabel Marant, whose penchant for ’70s-style prairie dresses and cowboy boots has translated into major commercial success.

Note: The above-mentioned are not the 1970s by way of polyester bell-bottoms or even the Studio 54–inspired, sensual dresses that defined Tom Ford’s 1994 to 2004 tenure at Gucci and made the brand synonymous with sex. Rather, Michele’s ’70s-infused pieces were soft-lensed and decidedly dreamy—the kinds of sheer, ruffle-trimmed house coats and pink prairie floral dresses, carefully accessorized with white sandals and matching bags, that 3 Women costume designer Scott Bushnell might have requested for the meticulously casual Millie, seeking to make an entrance at the pool at the Purple Sage Apartments, or her would-be doppelgänger Pinky Rose (Sissy Spacek), who trails in her wake.

![]()

Mick Jagger in the 1970s

![]()

Harry Styles in 2022

Michele understands that clothes maketh the character and his Gucci vision was always Hollywood movie-adjacent. He originally studied costume design and credits his film-buff mother (who worked as an assistant at a production company) with introducing him to the silver-screen classics. He opened his spring 2019 show with scenes from the 1971 experimental movie A Charlie Parker by the radical Italian theater duo Leo de Berardinis and Perla Peragallo. For spring 2022, he went one step further, staging his show on Hollywood Boulevard, filling the catwalk with all-eyes-on-me gowns worthy of Marilyn Monroe (that cipher of idealized femininity who so fascinated Andy Warhol), Elizabeth Taylor and Judy Garland. His last, for spring 2023, was modeled by 68 sets of identical twins inspired in part by the Grady twins in Stanley Kubrick's The Shining, a continuing obsession Michele explored in Gucci's autumn 2022 campaign by recreating scenes from Kubrick's most famous movies (with a little help from longtime Kubrick costume designer Milena Canonero). As usual, every look was styled to read irreverently unisex, down to the garters worn by male twins. No wonder when Harry Styles wanted to cement his transition from pop star to actor while promoting his latest movies, Don't Worry Darling (2022) and My Policeman (2022), he called on Michele to outfit him in a dark-green blazer pinned with a glamorous floral corsage, or a navy-blue suit with a shirt whose collar was so exaggerated it almost reached his breast pocket.

Styles, not so incidentally, is the poster boy for a new cohort of Gen Z men who wear feminine-leaning ruffles, lace and high-heeled shoes with casual insouciance—a cultural shift that gained ground with gender-bending stars David Bowie, Elton John, Prince and Mick Jagger in the 1970s. Styles, a close friend of Michele, is equally enamored of the decade: He drives a primrose-yellow ’72 Ferrari and is rarely photographed without his Gucci Jackie bag, a style that was designed in the 1950s but found fame years later thanks to its synonymy with Jackie Kennedy. “Masculinity is evolving and it’s being partly led by Gen Z,” says Lucie Greene, founder and CEO of New York–based trend forecasting agency Light Years. “They are pretty much the most gender-fluid generation to date. They see themselves as creatives and activists, and that chimes with the ’70s.”

![]()

Oil crisis, 1973

![]()

Protest signs against Russia’s War on Ukraine, 2022

Freedom, more than anything, seems to be what people admire about the decade. Sexual liberation, environmentalism, gay rights, women’s rights, civil rights—all kinds of liberties were being debated in the open, with protest marches marking the decade. “This was all post-Woodstock, so a new generation was shaping the political conversation, especially around Vietnam and peace for the world. Earth Day was born around then,” recalls Ed Burstell, a retail consultant and former managing director of Liberty who was part of the hedonistic New York party scene in the ’70s. Burstell sees a modern parallel in today’s oppressive news cycle dominated by war, with inequality spawning the #MeToo and Black Lives Matter movements. “Today, we have war on women’s reproductive rights, still no energy independence, and art is just for the rich. It all makes sense that we want to go back to the hope and the spirit of the ’70s.”

The vintage trend that has been slowly gathering momentum for years seemed to be peaking in 2022—fuelled in part by Licorice Pizza, Paul Thomas Anderson’s love letter to sun-dappled 1970s style. (Costume designer Mark Bridges leafed through high-school yearbooks and old Sears and Montgomery Ward catalogs to craft Alana Kane’s San Fernando Valley-in-1973 look, chock with halter tops, corduroy pants and big-collared minidresses.) But the liberation of the 1970s often manifested in style that had less to do with labels and more with one-offs. After the ’60s boom in mass-produced fashion subsided, secondhand shops (no one had coined the idea of “vintage” back then) were where discerning shoppers hunted for jumpsuits, sharp tailoring, diaphanous dresses, soft blouses, midi skirts, and heels that were high but that you could walk in. The urge to be creative—partly influenced by economic anxiety—meant old ladies and young people alike picked up knitting needles and crochet hooks and began making their own clothes. You can feel that experimental mood manifest in 3 Women most explicitly in the character of Willie Hart (Janice Rule), the titular third woman who spends her days painting mythological murals in empty swimming pools, their fantastical subject matter belying the blankness of her expression and the gray shapeless pioneer-style smocks in which she drifts around the desert. But it’s also there in Millie’s banal monologues detailing everything from painting and upholstering an old sofa to the new craze for hula dancing (“I think it’s sexy”). And it’s there in Pinky’s hasty running up of new pink girlish outfits on her sewing machine to wear to work the next day. In fashioning themselves creative identities, all three are inventing a new reality, but in very different ways.

![]()

Gloria Steinem at the International Women’s Day March in New York City in 1975

Switching up shopping habits and clothing choices, as we see with Millie at the close of 3 Women, can spark seismic shifts in personality. After having moved in with Willie and Pinky, forming an unlikely nuclear family, Millie drops the “thoroughly modern” veneer she learned by rote from magazines and movies. Shrimp cocktail from a can is no longer on the menu, color schemes and dating tips no longer make up the chatter, the sunshine-yellow bikini with the carefully coordinated toweling cover-up has been packed away. Instead, Millie begins to dress like Willie, in old, gray clothes, sweeping back her perfectly coiffed fringe, and assuming Willie’s role as the landlady of the tavern and the mother figure.

According to director Robert Altman, speaking with The New York Times in 1977, the most significant line in his film comes at the end: “You’re gonna help me fix dinner tonight,” Millie says to Pinky. “The vegetables need washing.” No more instant junk food. No more languid yellow dress. No more sunny-hued dreamscape. Potatoes need peeling, the pool needs cleaning. Society’s lies and delusions have been scrubbed away like the dirt sticking to a tuber, revealing something altogether earthier beneath.