Retracing 3 Women

By Emma Cline

3 Women, dir. Robert Altman, 1977

Retracing 3 Women

Emma Cline

What remains of Altman’s desert?

July 1, 2023

The colors are what I think of first. Almost Easter candy colors, the pale yellows and lavenders, and their cousins, the deeper daffodils and purples, the baby pinks.

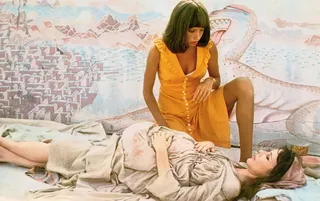

Then the women, of course. Sissy Spacek as Pinky with her dusty, wide-open face, the sheet of fawn-colored hair down her back. Shelley Duvall as Millie—those eyes!—chattering away with her McCall’s advice, the inane instructions for womanhood that grow more and more ominous for their rote repetition. So much of the movie seemed to touch on the humiliations of femaleness and the grotesqueries involved in trying to get it right: Millie’s recipes organized by the time it takes to cook them, Pinky spilling jarred shrimp cocktail on her dress, Millie flirting with the doctors in the cafeteria who don’t bother to look up from the newspaper, from their melon slices.

“What’s wrong with you?” Millie asks Pinky.

“Nothing,” Pinky says guilelessly—it’s the wrong answer, we understand instantly from Millie’s stricken expression, and not only because Pinky is meant to pretend to be one of the elderly, afflicted patients at the health spa, but because the entire enterprise of womanhood requires you to know that there is something wrong with you.

The colors and the women—I think of these first and then of the background that Robert Altman sets them against, the dusty leached landscape of the California desert.

3 Women was filmed in the Coachella Valley in 1976, over six weeks. I decided to go to Desert Hot Springs, out between the San Jacinto and San Bernardino Mountains, for a few days from Los Angeles in February of last year. The previous month I’d been asked to choose a slate of movies as a guest programmer for a movie theater—I thought of 3 Women instantly, and the strange, hypnotic film had been on my mind ever since. I had some idea of trying to find a few of the old film locations while I was in the desert, to learn what still exists, if anything. Altman’s film is so surreal, so untethered to an actual world, the possibility of any present-day traces remaining seemed unlikely, like encountering leftovers from a dream.

The main drag of Desert Hot Springs is lined with low, putty-colored buildings and the usual creep of chain restaurants and stores. Off that main road, I drive through housing developments ending abruptly in desert, a pet cemetery, and a massive cannabis-processing facility fortified by electronic gates and security cameras and what looks to be an armed guard. Overwhelmingly it’s a place of browns and terracottas, palm trees with their crusty exoskeletons, layers of choppy bark and the cutout shadows from the fronds. There are modern spa resorts dotted here and there, built for the mineral waters that have been the town’s main draw since its founding—Altman used one of these resorts as a chief setting of the film, the health spa where Pinky begins a new job under Millie’s tutelage. The hotel where I stay has concrete pools filled with lithium waters perpetually running from pipes built up with calcified mineral deposits. A somnambulant feeling dominates, everyone looking a little dreamy. No one quite catches my eye. Occasionally you hear the highway, a motorcycle whining past.

When the heat of the day gets to be too much, I go back from the pool to the rented room and watch Altman’s movie on my computer with the curtains drawn. Spacek’s character, Pinky, is always doing some peculiar, wrong thing—blowing bubbles in her Coke, salting her beer, looking at everyone too long. There’s a visceral discomfort in watching her, and in watching Shelley Duvall as Millie, too, though the flavor of that discomfort is different—something feral and uncivilized and animal in Pinky, a lack of awareness, whereas Millie is a tightly wound doll, her big eyes staring into the middle distance as she blabbers to no one in particular, straining to perform correctly.

I forgot how painful certain scenes are. Millie’s feverish preparations for a dinner party whose guests cancel at the last minute. The odd little terry cloth hooded robe she wears down to her apartment building’s pool, the other tenants not even bothering to pretend they aren’t laughing at her. It’s embarrassing to be a woman, to submit yourself to its vulnerabilities. And it almost doesn’t matter whether the embarrassment comes from not knowing the rules, like Pinky, or believing you know them all, like Millie.

Sissy Spacek and Shelley Duvall in 3 Women

“SO MUCH OF THE MOVIE SEEMED TO

TOUCH ON THE HUMILIATIONS OF

FEMALENESS AND THE GROTESQUERIES INVOLVED

in TRYING TO GET IT RIGHT.”

I’ve been listening to a funny psychology podcast by three Jungian analysts, and their way of seeing symbols in everything has colored my rewatching of the movie. The problem with the Jungians, though, is that I keep putting on this podcast as a way to fall asleep, and I never actually make it through an episode. I wake at weird hours of the night to find the Jungian analysts solemnly conversing about something I don’t understand at all, deep in some new topic entirely. As a consequence, I have only a piecemeal sense of their talks. It also makes my dreams stranger than usual. Something about that semi-wakeful state seems appropriate for 3 Women. When I bring up the movie at a party in L.A., a woman says, “Oh, I love to fall asleep to that movie.” People kind of laughed at her, like this was a ridiculous thing to say. I know what she means. But I also knew this woman ten years ago, when she went by a different name entirely.

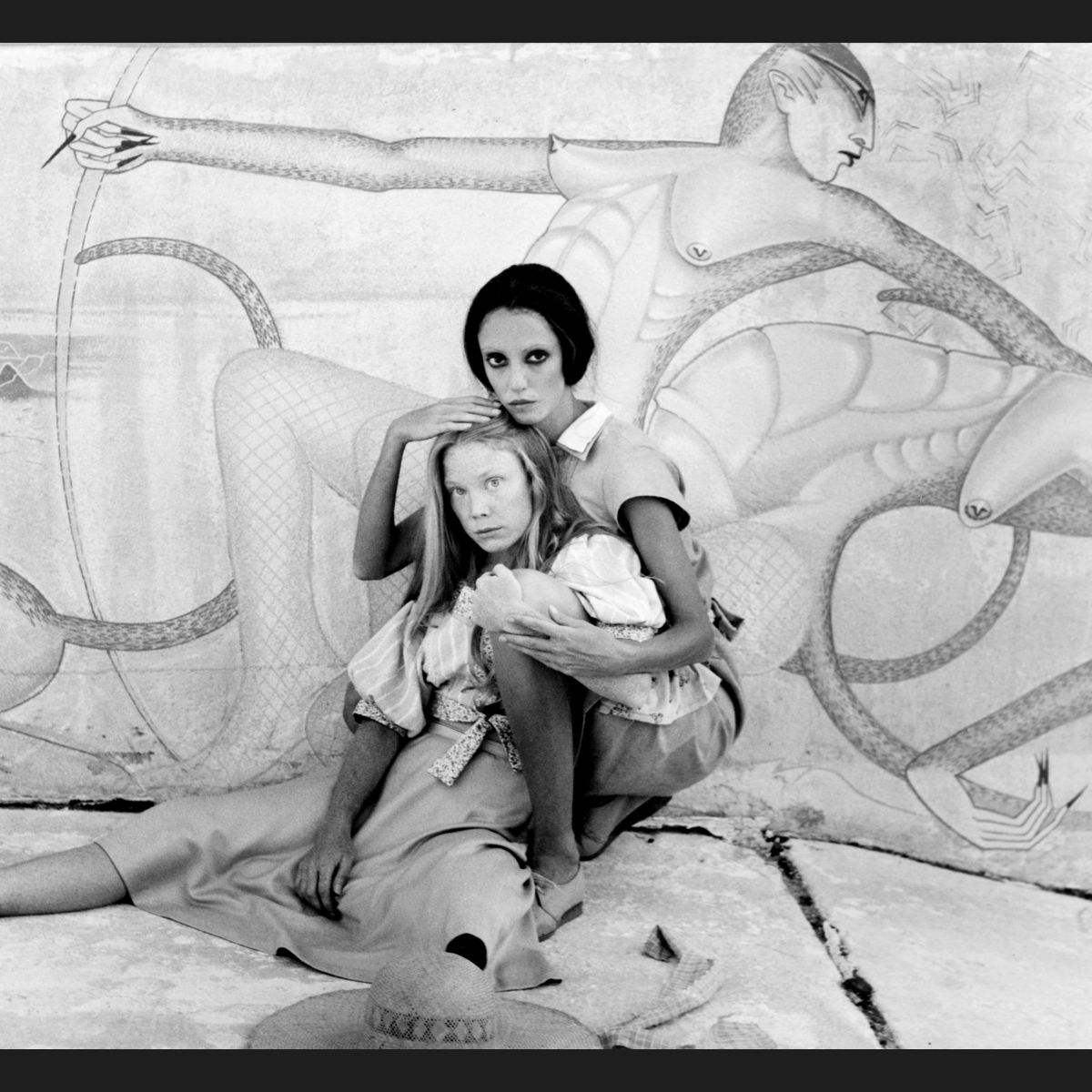

The whole movie feels like it makes visible a dream logic, a frightening world beneath the known world. Altman said the idea for the film came to him in a dream, these two women taking on each other’s identity, and was partly a response to Ingmar Bergman’s Persona (1966), another film that distresses and disturbs and explores the porous nature of self. Like Persona, the plot of 3 Women is difficult to pin down—a young woman comes to a desert town, meets another woman. They move in together. After an accident in a pool, they seem to have swapped identities. 3 Women is haunted by a third woman, Willie, a pregnant artist (played by Janice Rule) whose presence is more spectral than human.

For a movie set in a desert, the visual texture of 3 Women is so watery and fluid. Altman constantly returns to images of swimming pools, the way water distorts and holds the characters. The pools act as portals to another realm, as reprieves from the desiccated world above ground. The opening shots show disembodied legs and torsos moving in a pool, the outlines of bodies shifting and warped: They are patients, we learn, at the health spa where Millie and Pinky escort their charges through the healing lithium pools. Then the swimming pool at Millie’s apartment complex, the site of Pinky’s accident, a swimming pool that seems to exert a menacing gravity, the painted murals shimmering beneath the water. Then there is another swimming pool, empty, at the desert hangout bar, Dodge City.

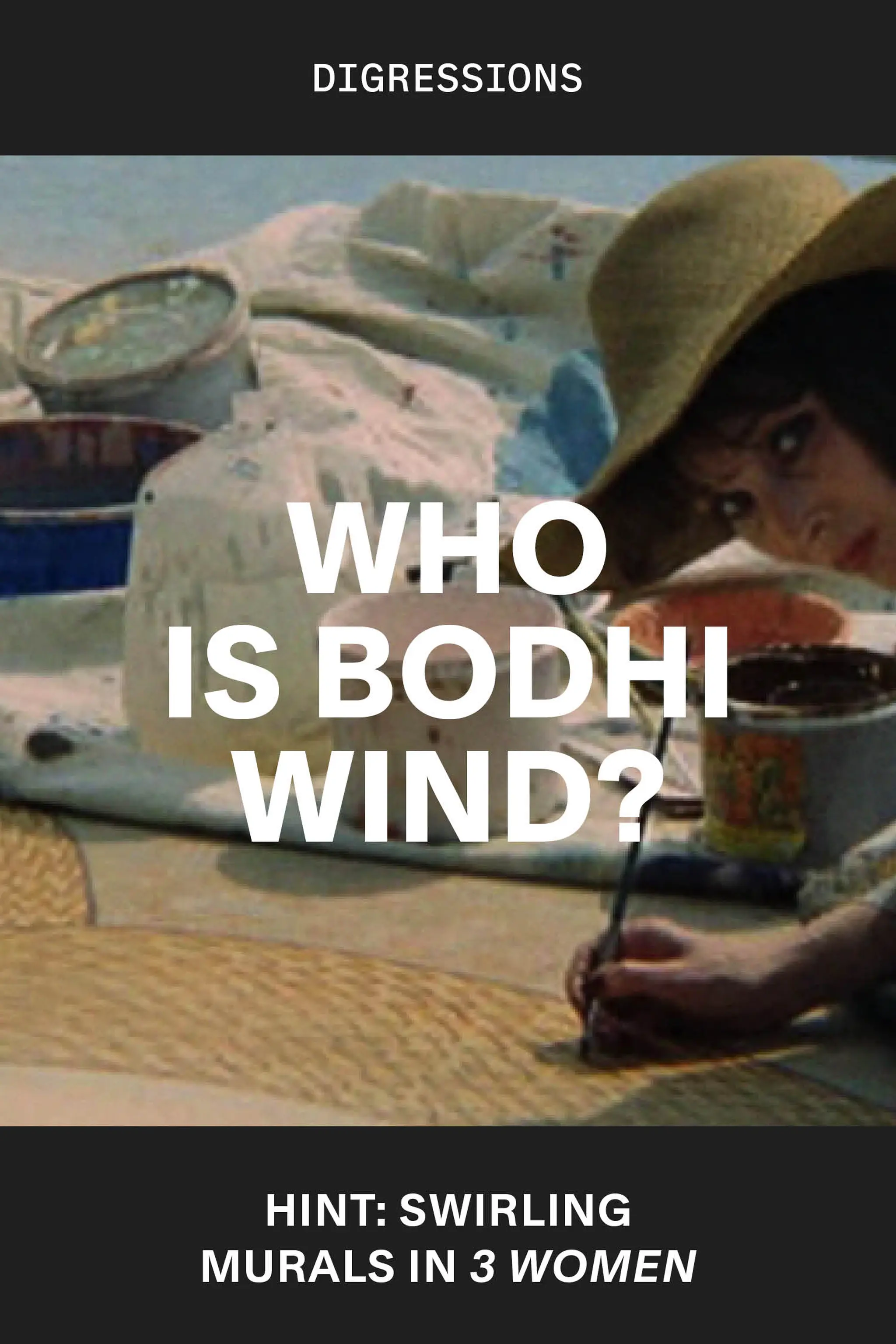

Altman hired the artist Bodhi Wind to paint the murals on the pools, the horrible creatures twisting across the pale blue surface of the drained pool or wavering beneath the water at the apartment building. These lizardy, witchy scrawls are Wind’s half-human, half-reptilian creatures—the Jungians on the podcast actually do seem to spend a long time talking about alligators and crocodiles, which they see as a kind of extra-human, primal fear, a symbol of the terror of what lurks in our subconscious, waiting to drag us under. The analysts might have something to say, too, about the female archetypes circling each other in the movie, the desert as a space that is both fecund and arid, life-giving and death-filled. Or maybe the analysts wouldn’t say anything like that—like I said, I’ve never made it through a whole episode.

When the movie is over, I go out blinking from my dark room into the blasted-bright sun. The air is still. An older couple in rash guards make their slow way from one end of a pool to another with the aid of foam noodles. A woman lies out on a wooden deck, copying passages from The Power of Now into a notebook. Her back is pocked with the ghost of cupping sessions, circles overlapping in various shades of bruise. A searcher.

We all stop what we’re doing to watch a roadrunner that comes out from the low brush and picks its way across the dirt path. The bird is brown and white, speckled, its tail raises and lowers. When the tail feathers catch the sun, there’s a flash of purple and blue. Big glassy eyes, like Shelley Duvall’s, and something of her performance, too, in its hesitant glance, one way and the other, the nervous inch forward.

I read about the official founding of the town of Desert Hot Springs—as a resort town, a health spa, a place that promises benefits beyond the mere fact of itself. The town was laid out by developer L.W. Coffee, who first opened a bathhouse in 1941 to provide access to the hot mineral waters. Healing waters became the town’s draw, advertised via old colorized postcards that show a Midge-like beauty lounging by an artificial blue pool. This Therapeutic Natural Hot Mineral Water Pool is maintained at about 105 degrees, the caption of one postcard says, the variegated faces of the mountains in the background. The promise that this place will transform you, heal you, or improve you—that feels particularly Western, too, the search and then the constantly renewed hope that the search has ended. Like hoping all your problems can be solved by drinking more electrolytes.

The three women

So much has disappeared since 3 Women was filmed in 1976. The mint-colored hotel where Pinky stays in the beginning is now an empty lot. The era of the movie, too, just looks so different, so much better—there’s a seemingly built-in harmoniousness in those old cars and the signage and the clothing, though it might just be a form of insistent nostalgia to think so. The apartment building where Pinky moves in with Millie still stands in Palm Springs, though all that purple has been painted over in a flat brown. The place spent an incarnation as something called the Life’s Journey Center, according to the sun-bleached sign out front. When I call the phone number on the sign, the operator recites that the number has been disconnected. The Life’s Journey Center, I learn from googling, was “a private state-licensed and certified alcohol/drug detoxification and residential treatment facility for the recovering adult.” The place looks abandoned, though there’s water in the pool and disassembled furniture in a jumble on the patio, a cross hanging on the wall.

I had spent some time trying to find the present-day whereabouts of Altman’s locations before I left for Desert Hot Springs. My main source of information is Ron’s Log, a Typepad website subtitled “Life in the desert.” Ron dedicated more than a few blog entries to the search for these locations, and I find his posts to be a total delight, as is the mild drama that takes place among fellow enthusiasts in the comments section. It’s so enjoyable—the work everyone has done to find these disappeared places. Someone posts an article from a 1977 issue of Palm Springs Life magazine, while another commenter offers a link to their collection of screenshots to aid the search. I learn that the Greyhound station—where Millie drives her butter-yellow car to pick up Pinky’s maybe-parents after Pinky’s accident—was for a time a burger restaurant called Woody’s. Another filming location, the Purple Sage Apartments, where Pinky moves in with Millie, was only identified in 2010, after a Swedish man reached out to Ron’s Log to share that he was a guest at a place called the Sunbeam Inn in 1976 while 3 Women was being filmed there and could confirm that Altman had used the Sunbeam Inn as the Purple Sage Apartments. “A major advance,” Ron crowed on his blog, and it is—all these strangers collaborating to rebuild a disappeared world.

An actor from the film—a small role but memorable, as the handsome Dr. Maas, who lords over the health center like a minor god and eventually discovers Pinky’s falsified identity, prompting Millie to quit—chimes in to identify the health center as Coffee’s Bath House and confirms this fact based on a postcard tacked to a bulletin board, visible in a brief millisecond of the film. Out of curiosity I send him a message. He no longer remembers where exactly they filmed those scenes. He can’t help me. It makes sense—he wrote his original comment some 14 years ago. Still, it feels fun to hear from him, engage in the low-stakes mystery of triangulating these locations. It’s like a version of holding a séance for the past, hoping that some specter will make itself known across the decades, believing that the things that happen leave some trace in the world.

The Bodhi Wind murals are mentioned in the 1977 Palm Springs Life article that Ron posts on his website: “The bizarre creations have caused a stir among Los Angeles media.” Bodhi Wind is dead, too, died young, hit by a car at age 41. In a New York Times article, also from 1977, he talks about how inescapable the heat was while he painted the murals. How his paint went dry on the brush or melted off the pool’s surface, the fumes making him “psychotic,” the heat plaguing him with an “oppressive feeling.” One hundred and twenty degree days during filming in August 1976.

It’s February now and only gets to 80 degrees. I read in the shade of an unflattering sun hat that makes me look like a preteen reptile enthusiast. I get up to drink water. I eat some of a Ritter Sport and a wedge of a very bad mandarin orange I brought with me from my neighbor’s tree in L.A. Then back in the water. The lithium water is meant to have health benefits—what benefits, exactly, I don’t know and don’t bother to find out, but the effect is that you’re constantly trying to gauge whether you’re experiencing some benefit.

I think I see the Power of Now woman lounging in a different pool. No, I realize, it’s a different woman, also reading The Power of Now.

“We don’t like the twins,” one of the women at the health spa says to Pinky.

Dodge City was the location I was drawn to most from 3 Women. The old-timey bar and dirt-bike track and overgrown miniature golf course where Millie brings Pinky at the beginning of the film, a space that ends up feeling like the mystic locus of the movie. When we first encounter it, it’s run by the bloviating Edgar, a former stand-in on a Hollywood television show. (“Stunt double,” Edgar corrects Millie and Pinky, before pulling a shiny silver pistol and pretending to kill a rubber rattlesnake.) Willie, Edgar’s wife, haunts the edges of Dodge City, working away at her mural in the bottom of the pool (one painted by Wind), her face hidden in the shade of her hat.

I held out some hope that of all Altman’s filming locations, Dodge City might still be there. It felt particularly Western—in its literal Western kitsch, of course, but also for the ways the idea of Dodge City embodies Western pleasure, the landscape as a theater of fun, an environment built up for human enjoyment: the shooting range, the dirt bikes cutting across the dust, the hubris of a swimming pool in the middle of a desert. One of those places that exist by sheer force of human will.

Dodge City proved to be the trickiest location for the enthusiasts to find. The amateur sleuths of Ron’s Log pored over historical surveys and photographs and real estate listings, analyzed the film still by still. One searcher writes of inching along a particular road while referencing images from the film, using “specific electrical towers (west) and mountain ranges (east)” to aid his quest.

There were false leads and dead ends, but after six years a commenter named Marshall is confident he can definitively identify Dodge City’s location, a place called Hidden Springs Ranch Club in Thousand Palms—he was able to find it only after an aerial survey from 1972 was put online, the final piece of the puzzle.

Marshall posts the survey image that he’s annotated with a helpful list of the points of interest:

1) Dodge City parking lot

2) cantina

3) swimming pool

4) distinctive, "tripod-shaped" sidewalk (later to have Bodhi Wind artwork)

5) small brown hut visible in some scenes

6) Willie's house

It’s a plant nursery now. The bar is gone, the dirt-bike course is leveled. Not much to see, is the gist from the commenters, but I drive out to Thousand Palms anyway.

“…SOME VERSION OF

MAPPING TIME,

EVEN IF FROM A MOVIE

GRAFTED ONTO

REAL LIFE.”

The road cuts past the spooky wind turbines, then a whole stretch of emptiness that, when you look again, starts to piece out into dirt and rocks and scrub and trash. If I drive over 20 mph, a faint whistle starts up from my passenger-side window—it’s stuck in a not fully closed position. I’ve had this car since high school, and only now is its inevitable decline too much to ignore. I’d like to pretend this will be the only problem, this stuck window, but it’s one of a hundred problems, the car breaking down, time asserting its dominance.

What am I looking for here, sitting in my car in the nursery’s parking lot? It feels like straining to discern some benefit from the lithium waters I’ve spent hours poaching myself in. I’ve done these sorts of things often enough to know that mostly these pilgrimages to meaningful sites are a letdown. My desire for some heightened experience encounters the absolute refusal of the place to offer it.

There are rows of potted fire sticks, squat palms, the smell of a nearby horse farm. I park, I get out. I walk around. I go back to the car to look at the aerial survey again. I swipe through screenshots from the movie, studying the exact shape of certain trees, memorizing telltale lilts to their trunks, then try to locate them around me. Trees, I think: Surely this isn’t a part of the state where they can afford to cut down trees. But they have—I can’t match any of the trees from the screenshots to anything I see.

Maybe the actual site was a little ways down. I walk farther down the dirt road, peer over a cinder block fence. There’s a massive Kokopelli on the side of a house, as big as the front door. The kind of yard that I associate only with the West—blue plastic tarps, fat tires on their side, the skeleton of a Quonset hut. Mess that may or may not have some organizing principle—could be a work in progress or just total junk. This atmosphere—someone’s chaotic private kingdom—seems more akin to Dodge City. That’s wishful thinking. The commenters are right, the aerial survey is right: Dodge City was razed, paved over, and now is the nursery, just these rows of plants for sale and a modular office. More wishful thinking, hoping that the Bodhi Wind murals might still exist—they’re too powerful. And they don’t: not here, not anywhere. The mural at the Purple Sage Apartments pool has long been painted over. The patio mural at the Dodge City set was destroyed and the other would exist only in the Dodge City swimming pool that’s either been ripped out or filled in with thousands of pounds of dirt.

Nearly fifty years have passed since filming. It would be strange if more remained. But it’s fun to search. The drive to the place instead of the place itself. The holding in your mind of the many iterations of history. Choosing to believe that reality crisscrosses itself, that the Bodhi Wind mural is just filled in by dirt and could one day be uncovered.

The Purple Sage Apartments building offers a little more armature for the desire to see the cinematic past in the very real present—the building is the same, the terrace railings are the same, the sign out front is the same, with the additions of a few metal curlicues. As one commenter posted, after seeing side-by-side photos of the Purple Sage Apartments with their present-day version on Ron’s blog: “Great find Ron and good pics of the ‘now’ proving it WAS the ‘then.’”

Proof that the “now” was the “then”—yes, that’s right, I thought. We want proof that what happens doesn’t just disappear, that there’s a relationship between the now and the then. Some version of mapping time, even if from a movie grafted onto real life.

The Power of Now, or The Power of Then and Now. Or whatever.

Altman’s film ends at Dodge City. The place is, for the first time, empty of men, occupied only by the three women of the film’s title. Interlopers appear in the form of delivery boys dropping off a shipment of Coke, but they are only temporary visitors to this world. Pinky, Millie, Willie: The characters have shape-shifted, taken on new roles, new realities, and Dodge City is their purview now. We follow Pinky and Millie walking barefoot by the Bodhi Wind patio mural, scrub grass growing through cracks in its surface. Pinky joins Willie on a porch swing. Before Millie reappears to tell them it’s time to come inside, Willie speaks.

“I just had the most wonderful dream,” she says, eyes on the horizon. “I was trying to remember it, but I couldn’t.”

It’s my birthday out in Desert Hot Springs, and then my birthday passes and it’s the day after my birthday, which I like much better. By late afternoon the sky has gone milky, all the hard flat colors washed into pinks and lavenders and heather blues. At sunset I walk out beyond the property to try and find the white owls my friends told me to look for in a particular stand of palms. They text me a little map they drew on a napkin.

OWL PALMS, it says. An arrow: VALLEY BELOW.

I stop a woman in Uggs, shorts and a puffer jacket out walking a big sheepdog in an empty lot.

“Around that bend,” she tells me. “That's where the owls live.”

My friends said it would be obvious. The first trees I see, I think, Oh, here we are, it is obvious. But then I see another group of palms, and these trees seem more correct. For whatever reason I scan the sky. After a bit I sit on the curb, tilt my face up. I strain for a sight of the owls, a flash in the dusk—there’s nothing. It gets darker. I keep waiting.