Who is Bodhi Wind?

By Michael Martin

![]()

Shelley Duvall in a promotional still for 3 Women, dir. Robert Altman, 1977

WHO IS BODHI WIND?

A quest to grasp the ’70s artist whose violent, erotic murals proved central to Robert Altman’s 3 Women

By Michael Martin

July 1, 2023

Robert Altman’s 1977 masterpiece 3 Women is a catalog of mysteries, and it’s only fitting that such a catalog would find its perfect illustration in Bodhi Wind’s hauntingly evocative murals. The late West Coast painter’s pellucid-bright depictions of primal men and women—ancient Egypt and Greek mythology are continual references—first appear in the opening credits. They continue to resurface, like dreams or apparitions, as the film unspools its questions of identity, sexuality and community.

In the fictional world of 3 Women, Wind’s murals are created by the last titular woman introduced: Willie, the mostly silent and heavily pregnant wife of the apartment building manager. She is seen painting her visions on the complex’s empty swimming pool. The murals themselves act like a silent Greek chorus that provides fodder for interpretation, if not answers or even clues to the film’s larger messages.

![]()

Janice Rule as Willie Hart in 3 Women

![]()

A Bodhi Wind painting featured in 3 Women

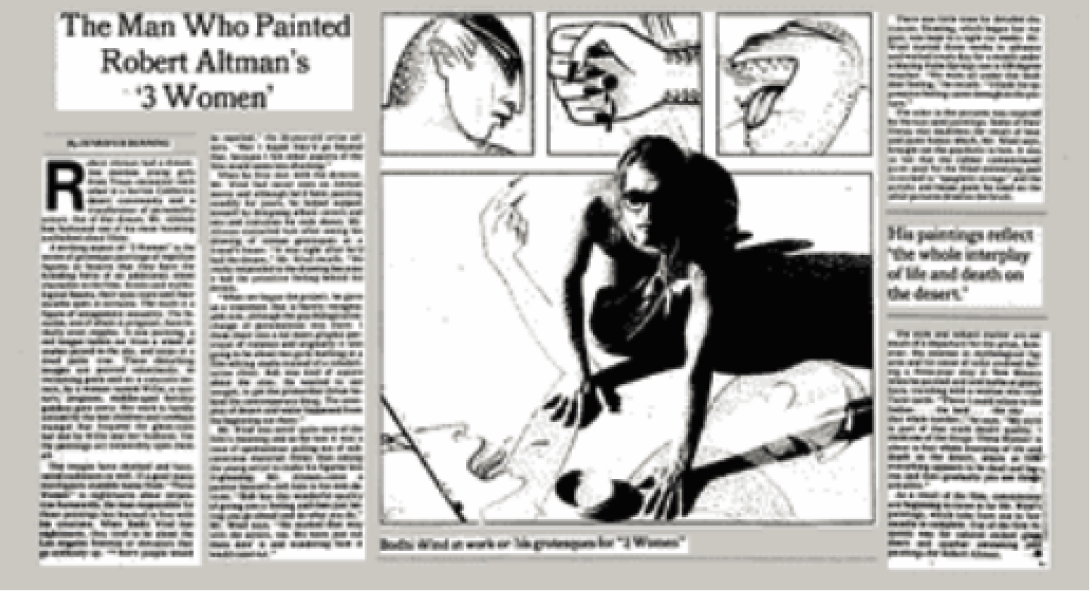

Notably, the newspaper ads for 3 Women gave Wind a prominent “murals by” credit. Nearly every review of the film (most of them positive) referenced the artworks. The Vancouver Sun called them “integral parts of the plot.” Altman used them as “violent murals of animal-men as forebodings of screaming madness,” offered The Arizona Republic. “Highly erotic and sadistic,” said the Santa Cruz Sentinel of the works, calling them, “as close as Altman will come to surrendering the keys to his theme.” It’s not every day that film critics turn to set design to help form their interpretation of a work. Perhaps that’s because many of 3 Women’s reviews noted that the film itself didn’t make much sense in a linear, literal or logical fashion. (Gene Siskel confessed that he watched the film repeatedly but didn’t understand it.) Why do the gawky, insecure Pinky (Sissy Spacek) and the vapid, consumerist Millie (Shelley Duvall) seemingly switch personalities only to become slightly more extreme versions, almost parodies, of the other? Your guess is as good as Siskel’s. The inscrutability of 3 Women’s plot, and the three women it contains, lends Wind’s murals a surprising narrative heft. So discussed were the works that The New York Times covered the artist and his paintings in 1977, describing them as:

… grotesque paintings of reptilian figures so bizarre that they have the brooding force of an additional, silent character in the film. Erotic and mythological beasts, their eyes stare and their mouths open in screams. The male is a figure of antagonistic sexuality. The females, one of whom is pregnant, have lethally erect nipples. In one painting, a red tongue lashes out from a wheel of snakes poised in the sky, and stops at a dead palm tree.

“HE WANTED TO USE IMAGES, TO GET THE

PRIMORDIAL THRUST BEHIND THE CONTEMPORARY THING.”

So who was this purveyor of such mysterious artistic visions (not to mention “lethally erect nipples”), this late-’70s sensation whose name seems born out of the very High Desert west in which his greatest works appeared? Details of the man are sketchy. Bodhi Wind was born Charles Kuklis in the North Side section of Pittsburgh in 1950. He attended Perry High School, where, on an art-enthusiast blog, at least one high-school classmate remembers him as a nice boy who was constantly sketching. In 1971, Kuklis changed his name to Bodhi Wind (Bodhi meaning “enlightenment” in Sanskrit) and moved to Santa Fe to pursue painting. He designed album covers and sets and costumes for rock acts (one of his clients, reportedly, was Cher). According to the New York Times article, Altman spotted one of Wind’s works—“a simian grotesque”—in a friend’s home and called him up.

“It was right after [Altman] had the dream” that inspired 3 Women, said Wind, who confessed that he’d never seen one of the director’s movies (not M*A*S*H [1970], McCabe & Mrs. Miller [1971] or Nashville [1975]) before talking with him. “He really responded to the drawing because it had the primitive feeling behind his dream.”

Wind accepted an offer to make paintings for 3 Women, for which Altman and screenwriter Patricia Resnick created a script treatment which has been reported to be somewhere between 30 and 50 pages long. Altman originally intended to film the movie without a screenplay (it was reported at the film’s release that Shelley Duvall wrote 80 percent of her own dialogue). “When we began the project, he gave us a treatment that is barely recognizable now, although the psychological exchange of personalities was there,” said Wind. “He wanted to use images, to get the primordial thrust behind the contemporary thing. The interplay of desert and water happened from the beginning out there.”

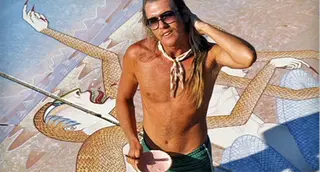

Article on Bodhi Wind in The New York Times, April 24, 1977

In a photo from the time, one of the only widely circulated photos of the artist, Wind looks like you’d expect a twentysomething painter in 1977 to look—long hair, permanent tan, era-appropriate shorts. Wind started the paintings for the film three weeks before the movie began shooting. He chose colors that referenced Navajo sand paintings. It was a high-pressure situation. “We were all under this lead-door feeling,” he explained. “I think the oppressive feeling came through in the picture.” Working in 120-degree temperatures in the Palm Springs desert, the paint fumes “brought out the psychotic in him,” he recalled. In the company of 3 Women’s personality-shifting characters, this impressionistic spirit seemed like an ideal match. Perhaps reviewers weren’t wrong to use Wind’s paintings as a foundation; since they were completed shortly before filming, Altman might well have used them as inspiration himself.

After this wildly auspicious cinematic debut, Wind seemed to drop off the face of the earth. He did exhibit with Tally Richards, a Taos, New Mexico, gallerist known as the area’s leading light in modern art. A 1982 review in the Taos News praised Wind’s Minoan- and Mexican-inspired drawings and “abstract casein works on paper” but challenged his paintings as dense, obtuse. “There is that feeling of yearning,” the writer wrote, “for a specifically painterly feeling.”

Unfortunately for Wind, 3 Women was essentially the end of the line. The conclusion of his life provided the cool irony of a latter Altman screenplay. Wind confessed in the 1977 article to having nightmares that tended to involve “the Los Angeles freeway or elevators that go endlessly up.” In 1991, at the age of 41, Wind was killed in a freak traffic accident. There is some mystery involved in the accounts: The November 29 issue of the San Francisco Examiner reported that Wind, then living in San Francisco, was struck and killed by a hit-and-run driver while he was waiting at a bus stop. In 1995, his hometown paper, the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, noted that he was struck while walking along a Los Angeles freeway.

![]()

Bodhi Wind

At the time of that interview, Wind’s parents were in possession of 17 of his surviving works. Not entirely lost to time, Wind has claimed a bit of Gen Z immortality online and on social media. Under the #bodhiwind tag on Instagram, one shot reveals a young man who replicated the only widely circulated photograph of Wind, shirtless and in those awesome ’70s shorts, for Halloween in 2018. You get the feeling even the limelight-shy artist would approve. “I think one of the things 3 Women is about is that whole interplay of life and death in the desert,” Wind said back then. “Where at first everything appears to be dead and barren and then gradually you see things are alive.”