Coppola's Conservationist

By James Bell

Apocalypse Now, dir. Francis Ford Coppola, 1979

Coppola’s Conservationist

Salvation artist James Mockoski reflects on two decades of restoring and protecting the films of Francis Ford Coppola

By James Bell

April 26, 2024

Film archivist James Mockoski joined Francis Ford Coppola’s production company American Zoetrope in the early 2000s. In the intervening years, he has worked closely with Coppola on restoring—and in most cases, significantly reworking—the director’s films, including The Godfather, Apocalypse Now, The Outsiders, One from the Heart and The Conversation. Mockoski is currently producing a documentary about the making of Coppola’s long-anticipated (and possibly final) feature, Megalopolis. We spoke with him about divining directorial intentions and the challenge of fine-tuning analog movies in a digital world.

From left: Dennis Hopper in Apocalypse Now; a poster for Apocalypse Now Redux

How did you first get into this line of work?

I grew up in Santa Cruz, California, which was an important filmmaking area in the silent era. I became involved in archiving because there was no place to protect the film history of the region. I studied film history at school, then I went to the University of East Anglia in England because it was one of the very few places that taught film archiving. There was a focus on protecting regional film history, which was exactly what I wanted to do for my community.

When did you connect with Francis Ford Coppola?

When I got back to the United States, I worked initially for UCLA, but not wanting to be in L.A. all my life, I wrote to Francis and explained that I was from the Bay Area and would love to come and work with him. It was at the time when they were recutting Apocalypse Now [1979] for the Redux version, which was challenging because there were literally millions of feet of film, and adding 45 minutes or so back in was hard. They found they needed to have a more formal archive and someone who could look after the collection. They wanted to go on to restore One from the Heart [1981], so they needed someone to rein in the material and to understand what was there.

How does Francis’s desire to work across genres and incorporate new techniques inform your work?

How that relates to restoration and archiving is interesting. I have the title of Archivist, but we wear many hats. Francis is not one to pigeonhole you. I’ve gotten more into postproduction, because a lot of skills you have as an archivist adapt well to postproduction, and through that I’m at the forefront of creating the very things that I will eventually archive. It’s dovetailed nicely. It’s unique—not a lot of archivists are able to ride both worlds. It can be nerve-racking, and it’s not for everyone. I didn’t think it was for me! But here we are, 20 years later. It’s been a fun journey.

American Zoetrope was founded on an ethos of ambition and disruption. Does it still feel like a place guided by that spirit?

Absolutely. I don’t think that philosophy has ever changed since Francis founded the company in 1969. The idea for American Zoetrope came about after George [Lucas] and Francis visited a company called Lanterna Film in Copenhagen. They saw young people making films in a way that was outside of any system, and it inspired them. No one was imposing rules or saying, “This is the way you make films.” Over American Zoetrope’s 55-year history, Francis has always retained that student’s mentality. He’s always learning, not doing the same film over and over again.

How much American Zoetrope material had been retained, and in what kind of condition did you find it when you started?

Francis is a pack rat—he kept everything. It was all in very good condition. Coming out of the Hollywood tradition, he knew that stuff wasn’t always looked after very well. Films were often tossed aside: Once they were out of release, they were gone. The Godfather is (1972) a good example. By the time that film went out of theaters, the negative had been run to death, so it was in bad shape when it got to the 1990s and he needed to do a restoration. Francis wanted to make sure that didn’t happen to the rest of his collection.

In the early 1980s, Coppola invited Old Hollywood figures like King Vidor and Gene Kelly, as well as others from overseas, like Michael Powell and Jean-Luc Godard, to come to the studio as creative advisors. Did these filmmakers influence his decision to retain his material through their cautionary tales?

They did, certainly. Another important figure was [Telluride Film Festival cofounder] Tom Luddy, who was the head of the Pacific Film Archive. Tom would bring hard-to-find films to Francis and educate him about preservation. That’s how we came to have prints of Eisenstein’s films, for instance—Tom made a trade for Godfather prints. He knew how precious these were. Francis was one of the very few filmmakers who actually controlled his assets. What we have can be astonishing—we have every single 35mm daily of Apocalypse Now, for instance.

It’s an unusual situation, in that you’re perhaps not doing as much of the initial detective work that is involved in a typical restoration. You have all the material at hand.

That’s true, though I’ve done detective work for other projects. For instance, the restoration of [Jonathan Demme’s 1984] Talking Heads concert film Stop Making Sense. That required detective work because the negative had gone missing for 30 years, and it involved tracking down which film labs had it at what time, how it went to various people and so on. It actually turned out that it was in the hands of Scott Grossman [Vice President of Technical Services] at MGM. I called him and said, “You have no business having this, but could you just check?” He called me ten minutes later and said, “You won’t believe this. It’s been sitting in a vault in Burbank for 30 years.” These are the crazy stories that are repeated through our industry.

How do things get lost?

Archives might take material in if the labs can’t find the owners, but a lot of times the material is shoved somewhere and forgotten. For Stop Making Sense, the negative was stored in a warehouse in downtown L.A., in a property that was going to be sold. Someone saw the Talking Heads name on the label, got hold of the band’s manager and said, “We’re closing, come and get your stuff if you need it.” The negative would’ve been tossed out if they hadn’t made contact—and I relied on that negative to reinstate two songs that had been deleted. That was lucky, but it’s a reminder of all those other films that wind up in the dumpster.

“What you hear today on any of the Apocalypse releases is based on that find in the dumpster.”

Is that a common experience?

There’s a similar story about Apocalypse Now. [Sound designer] Walter Murch found the six-track in the U.K. The master must have been sent there for the international release and never returned. Someone dumped it, but a guy who’d worked at Zoetrope happened to be there, and looking at the labeling on the boxes said, “This writing’s familiar.” He took it and stored it away, and then, when Walter was looking for it, called him and said, “I found this!” What you hear today on any of the Apocalypse releases is based on that find in the dumpster.

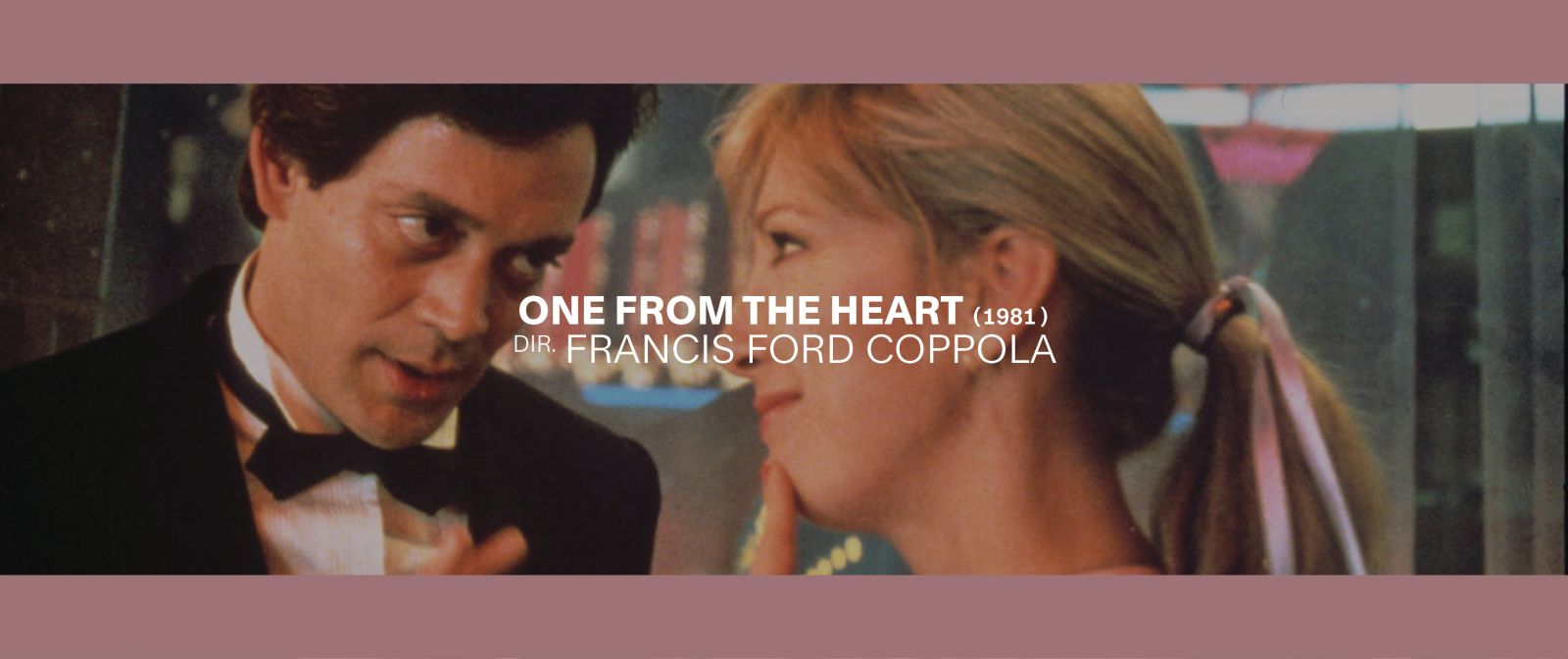

One from the Heart was a smaller production than Apocalypse Now. How did you go about creating the Reprise version?

It was actually one of the first projects I worked on when I started at Zoetrope. The challenge then remained as now: The negative had gone missing. It had all been shipped to Technicolor Rome because they were doing a recut there before the film’s [original] release. The original negative had been stored there, but at some point the river near to where the lab was had flooded. Thankfully, protection masters [a specially stored copy] had been kept.

For Francis, a restoration is never straightforward. He always says it’s an opportunity to do things that he couldn’t figure out back then or that he feels would work today, when the audience might be more accepting. He still likes to experiment with the presentation of his films. It’s not to supplant the original, it’s just an evolution or another way of trying to tell the story.

What was he hoping to change?

[For One from the Heart] there was not a version he felt was definitive. The Reprise version gets him closer to feeling that it’s the best it can be and that the experiment is done. It’s not the profound changes of Apocalypse Now Redux, where whole scenes were added. It’s an under-the-hood restructuring.

In the original One from the Heart, it gets to the argument [between the lead characters] too fast. In the Reprise version, it works up to it. It tries to show that there was love there in the beginning and how it fell apart. If you study Francis, you’ll find the films are always found in post. It’s in editing, it’s in sound—the script is always a work in progress. For a lot of filmmakers the script is the Bible, but for Francis it evolves even while shooting, which can drive a lot of people crazy.

From left: The Godfather Part III, dir. Francis Ford Coppola, 1990; Stop Making Sense, dir. Jonathan Demme, 1984

There was a recent controversy with Wong Kar-wai restoring his films and adjusting the color grading so that it was noticeably different from the original release prints. On One from the Heart, where color plays such a major part, were there similar temptations?

That’s always an issue. We had it with The Godfather, where some said that the color was different in the first Blu-ray release. But you look at any transfer from VHS on and there are going to be differences. How we look at a film now, on OLED TVs at home or on the Sony X300 in the color suite, has evolved. We try to keep it very close to the original 35mm answer print [the first version printed to film after color correction], but it sometimes won’t translate exactly on the monitor today.

My job is to look at the original 35mm print. That’s our guide, and I try not to deviate from that. But I have Francis in the room, and if he wants to do something different, that’s his prerogative. That said, Francis is generally very faithful to the look of the film and pays respect to what the DP does, so there are usually very few changes.

How accurate can peoples’ memories be of the original theatrical release, when there may have been wildly inconsistent conditions: cinemas with dim bulbs, scratched prints, variations in the darkness of the room, and so on?

Absolutely. It’s similar with sound, when people may say, “It didn’t sound like this.” Well, we’re not mastering on the same speakers that we had 40 or 50 years ago. Speaker technology has changed, so it’s not going to sound like it did in a theater that had a blown-out speaker 50 years ago! We get spoiled because we watch these films in a perfect presentation, but when it leaves into the real world, there are so many variables—and there were so many more variables when it came to 35mm projection. But I do feel we’ve come to a point in technology where, when I grade it in the lab and I take it home, my OLED TV is pretty spot-on. The differences are getting smaller and smaller.

Is there a point where the technology reveals additional details that people wouldn’t have seen originally and the archivist’s ethical dilemma about how far to take things becomes sharper?

There is. For example, when we brought out Apocalypse in Imax, the opening optical is so grainy, but if you take out that noise, you then start revealing a lot of the artifacts that created that element. So it’s not appropriate to completely remove that film look—that’s there by design too. It’s there to blend together that five- or six-layer optical. We might have technology to make it look sharp, but it would also look unnatural. We have to have a balance; we can’t go too far.

What was the approach when you restored The Outsiders [1983] and added in the extra material to make The Complete Novel version. Was Francis unhappy with the original?

No, he thought the original was perfect. The story originally came to him through a group of elementary students who’d read S.E. Hinton’s book in class. It was just after One from the Heart, when American Zoetrope was going bankrupt, and it came at a good moment because it pulled him away from the studio’s problems and made him start filming in Oklahoma. At the time he felt that people were familiar with the story, so he could make narrative leaps, and that people knew the characters, so he didn’t have to tell you completely who each one was. But after 30 years or so, Francis would still get letters asking, “Why did you cut out this scene?” Eventually he felt that people were not as familiar with the story as they once were, and he decided to go back and offer a more complete version—not to replace the original but to give the more complete experience that people kept asking him for.

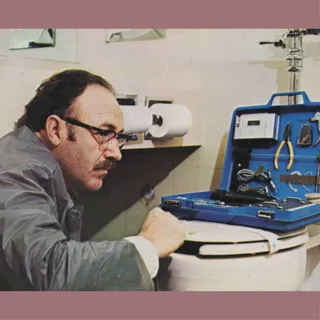

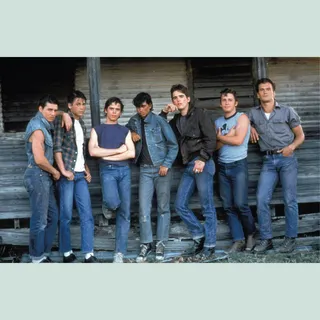

From left: The Conversation, dir. Francis Ford Coppola, 1974; The Outsiders, dir. Francis Ford Coppola, 1983

With The Godfather Part III [1990], which you recut in 2020 as The Godfather Coda: The Death of Michael Corleone, how much had the initially negative response to the film weighed on Francis? Was there a feeling that he could improve it?

When it comes to the original edits of these films, in many cases the release version came about from needing to get it done by a certain date. The Godfather Part III needed to be out by Christmas, so there was a rush to edit it. And even though it got released in theaters on Christmas Day, a couple months later Francis had Walter recut it for home video. And that home video release is what everybody really remembers. So even the theatrical cut changed instantly the moment it left theaters.

With the original release, I don’t think he was at all satisfied that it was done or complete. He would get studio notes saying, “Maybe you should start with a party and have that scene with the Vatican come later in the story,” and that never sat well with him. It took Francis some time to reflect, but 30 years later he felt able to go back to his original thoughts on how to structure the film.

You’ve just completed work on a new restoration of The Conversation [1974] for its 50th anniversary. That has always seemed such a perfectly contained film that it’s hard to see a need for any adjustments. Is it more of a straight restoration?

It is. I don’t have any of the footage, because none of the original material survives. That was made under Paramount, and the stuff that didn’t wind up in the film got discarded. But Francis will say it was a perfect film and it didn’t need to be touched—much like The Godfather. I don’t think he would have wanted to revisit it in that way even if he could have.

This restoration is based off of the original camera negative, which we had never used before for anything. It’s very faithful to cinematographer Bill Butler’s print, which he approved 20 years ago. It’s a faithful reproduction of what we think people would’ve experienced back in 1974.

What has your involvement been on Megalopolis?

There’s not much I can reveal. Francis has been dreaming about and working on this film for the last 40 years. We had stuff shot 20 years ago, before that got derailed by events. So we’re very excited to finally get his vision out. Strangely, it dovetails with One from the Heart, because Francis first started writing the Megalopolis script while working on One from the Heart. So it’s a nice bookend.