Home Invasion

By Hideaki Fujiki

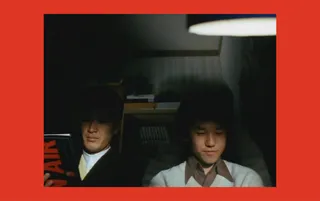

The Family Game, dir. Yoshimitsu Morita, 1983

Home Invasion

Taking one Tokyo household as its subject, The Family Game brilliantly depicts the human cost of Japan’s industrial boom

By Hideaki Fujiki with Robert Bound

April 26, 2024

Released in 1983 and set in the same period, The Family Game quickly became regarded as groundbreaking in the Japanese film firmament, offering a satire of contemporary Japanese society and bucking the conventions of the family genre—namely, positive portrayals of stolid home life in a booming nation. Despite being played naturalistically, Yoshimitsu Morita’s film is immediately sly, absurd and arresting: A boy feigns illness to skip school, his brother starts a classroom fight over a pencil and their traditional two-parent, two-child household is upended by the arrival of a surly and opinionated private tutor, who installs himself as an incongruously wild presence at the formerly subdued family dinner table. Within the opening five minutes, it’s clear we are in for major disruption.

From left: Yūsaku Matsuda and Ichirōta Miyakawa in The Family Game; Top Stripper, dir. Yoshimitsu Morita, 1982

Over his 30-year career, Morita steered an electrifyingly eccentric course through genres, making everything from melodramas and romances to hard-bitten crime flicks and erotica, including two Nikkatsu “Roman Porno” films (a surprisingly common path to mainstream filmmaking for Japan’s auteurs until theatrical releases could no longer compete with the rise of adult video for home viewing). The Family Game, widely considered Morita’s breakthrough, was swiftly adapted from a 1981 novel of the same name by Yohei Honma, which had won major Japanese literature awards. Morita’s film also enjoyed critical success, earning eight Japanese Academy Award nominations (with Best Newcomer of the Year going to Ichirōta Miyakawa) and winning the well-regarded film magazine Kinema Junpo’s award for Best Film of the Year in 1984.

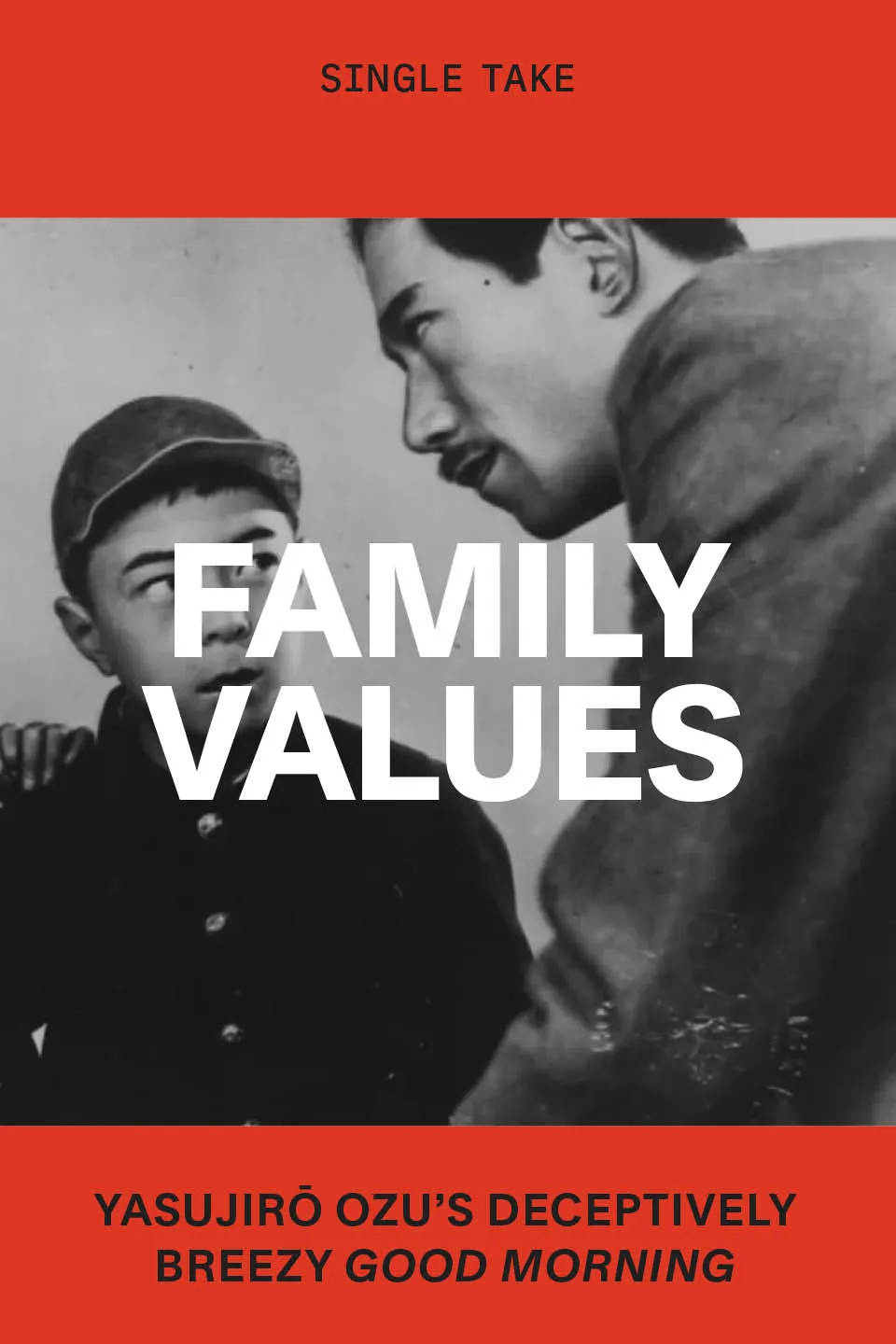

The Family Game challenged a longstanding convention in the rich field of Japanese domestic drama that included Yasujirō Ozu’s films from the 1930s to the early 1960s, Daiei’s motherhood melodramas from the late 1940s to 1950s, Shochiku’s “home dramas” in the 1950s and television dramas from the 1960s to the mid-1970s. The arrival of “pink films” and Nikkatsu Roman Porno, which portrayed danchi (high-density residential tower-blocks built to house the expanding nation) in the 1960s and 1970s, began to disrupt this harmonious familial image. The Family Game entered the fray with a further provocation: Was the idealized nuclear family secretly dysfunctional after all? Was it just another structure? In the 1960s Japan largely believed in the pull of prestigious universities and companies—surely they would lead to economic stability and happiness! But by the 1980s, when the economy was booming, the three tendencies of youthful “deficiency”—apathy, indifference and irresponsibility—came to be widely recognized. The Family Game implies that this phenomenon was a natural consequence of the family being a miniature corporation of its own, and hints at the madness built into the systems the nation created to make itself great.

The Family Game centers on the Numata family and their sons’ schools, both of which exemplify and symbolize the regimented convention. The Numatas are a typical nuclear family: father Kōsuke and mother Chikako; their first-born son, Shinichi, a high school student; and their second son, Shigeyuki, who is in junior high school. This setup—the husband earning outside the home, the wife essentially an unpaid domestic worker—was dominant from the 1960s and helped sustain the social circumstances in which the Japanese economic miracle was rooted. The boys’ schools also adhere to the standard pedagogy: a mass education of 30 or 40 children per class, taught efficiently, often by rote. A place where hierarchy is key.

The Numatas’ danchi and Shigeyuki’s school lie in the coastal industrial district of Toyosu in Tokyo, linked at the time of the film time by a ferry to Tokyo’s main districts (a subway line replaced the ferry in 1988). Morita frequently shows factories’ smoky chimneys, reminiscent of Ozu’s domestic dramas of the 1930s. Both filmmakers also depict salaried workers’ settlements in newly developing districts, expanding urbanization and suburbanization. Where Ozu’s smokestacks suggested industrial progress, Morita’s chimneys in The Family Game seem to intimate both that progress and the subsequent environmental problems that were becoming acknowledged in ’70s Japan. The neighborhood is gloomy and confined, with a seamy side: Women with smudged makeup and tousled hair hurry through the streets and corridors of the tower blocks.

Morita is as keen to raise his eyebrow ironically as he is to dissect societal change with laser precision. From the film’s outset, the family’s habits are disturbed by Yoshimoto, the tutor they have hired to help boost Shigeyuki’s grades. With the rackety swagger of a private investigator (rather than the quiet discretion expected of a private educator), Yoshimoto rides the ferry from central Tokyo into the Numatas’ occluded territory and materializes, like a stranger abroad in a Western, ready to act as the audience’s guide and question the rituals of a community that seem so normal to those on the inside. He’s the film’s irreverent revolutionary.

“The Family Game entered

the fray with a further provocation: Was the

idealized nuclear family

secretly dysfunctional after all?”

One of those norms is the ranking within, and of, Japanese schools. In the Numata family, father Kōsuke decrees that his sons must work hard to get into the most prestigious colleges. Chikako doesn’t just urge her boys to study, she’s worried about Shigeyuki’s marks in his examinations. In private, the parents discuss their children purely through the prism of their school achievements. Making the grade is all-important to the family “firm” and its future.

This focus on educational standardization and status mirrors the family’s patriarchy. Everything in the Numata family is sacrificed for their sons' studies, as meted out under the father’s authority. Chikako tells Shinichi, “You’re a freshman. But don’t relax. Study hard. Otherwise I’ll get in trouble with your father.” She speaks with Kōsuke in their parked car saying, “I sometimes wonder why we sacrifice ourselves for the children so much.… I just want to learn jazz dancing.” In another car scene, Kōsuke attempts to bribe Yoshimoto, promising him a sizable reward for boosting Shigeyuki’s marks. The adults take to the car to share secrets and hatch plans. But the car literally doesn’t move; they go nowhere.

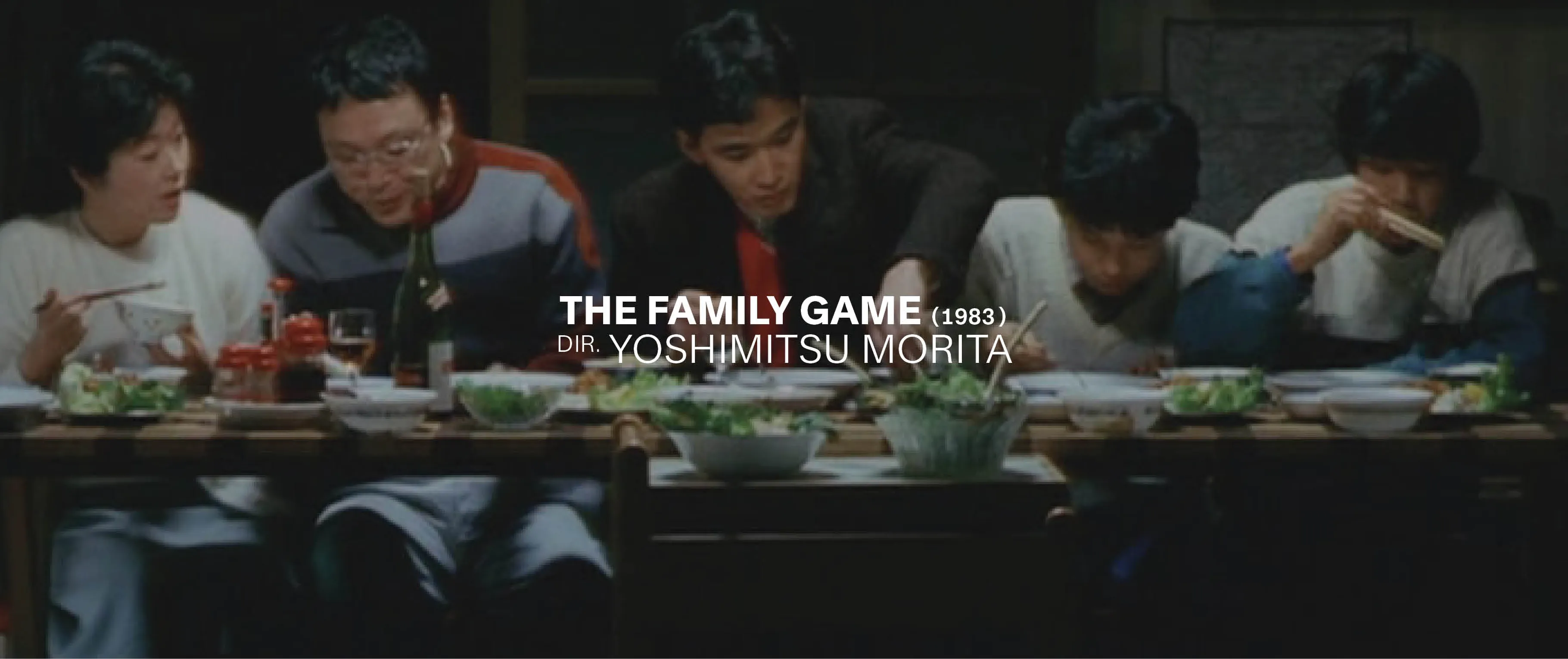

Morita’s family can’t really talk to one another, an impoverishment that is rendered visually, comedically and exquisitely in the film’s infamous mealtimes. Here we see the family lined up side by side at the dining table, rather than sitting around it and facing one another. It’s a framing reminiscent of a factory production line or the rows of dark-suited men at noodle bars, refueling for the next assignment.

The boys’ school and home life offers a binary choice: to accept the norm and work hard to satisfy it, or to reject it and become indifferent to the consequences. Throughout the film the former is represented by Shigeyuki, initially apathetic—except when engrossed in his toy roller coaster—but increasingly industrious about raising his grades. Shinichi, initially praised as a high-achiever, gradually becomes uninterested in school (except when it comes to a female classmate). Yoshimoto’s methods of tutoring, meanwhile, might charitably be described as unorthodox: He murmurs about diligence while proffering a book of botanical illustrations that has nothing to do with the boys’ studies. After Shigeyuki returns from school with a bloody nose, Yoshimoto assures him, “After we’re done studying, I’ll teach you how to fight.” He pockets a stash of porn mags that have been sent by a school rival to embarrass Shigeyuki at home: “I’ll look after these and you start studying.” Yoshimoto is a disruptive force in the Numatas’ life, never failing at mealtimes to dispatch his wine in one slurp, and ultimately bringing vitality and antic energy to their black-and-white existence.

From left: Saori Yuki and Yūsaku Matsuda in The Family Game

On the one hand, Yoshimoto and the stranger in a Hollywood Western are alike: an outsider breezing into town and leaving it changed at the end. But whereas the Western hero rides out of town after serving order and justice, Yoshimoto ultimately destroys any semblance of calm that the family possessed—the final, famous dinner scene becomes a riotous mess, with our tutor hurling noodles and pouring wine like kerosene over a condemned house. Yoshimoto has proven to be an agent of chaos, but could he be, after all, the simple result of the system he’s bucking?