Larry Kramer at the Movies

By Bill Goldstein

Larry Kramer at the Movies

The iconic gay-rights advocate got his start writing scripts in the film industry. Kramer’s official biographer explains how his movie work broke taboos and earned an X rating in the U.K.

By Bill Goldstein

June 28, 2024

The year 2024 marks the 55th anniversary of the Stonewall riots. When that milestone in gay liberation erupted, the writer Larry Kramer, soon to become one of the most significant activists of the post-Stonewall era, was nearing the end of a decade working in the movie business in London. He turned 34 on June 25, 1969, three days before the start of the riots. Larry didn’t know about Stonewall—there were no reports of it in London—but it wasn’t only his birthday he was celebrating that last week in June.

![]()

Larry Kramer in 2009

![]()

The Normal Heart, dir. Ryan Murphy, 2014

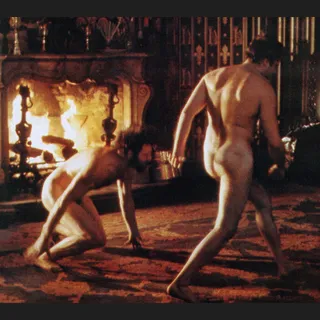

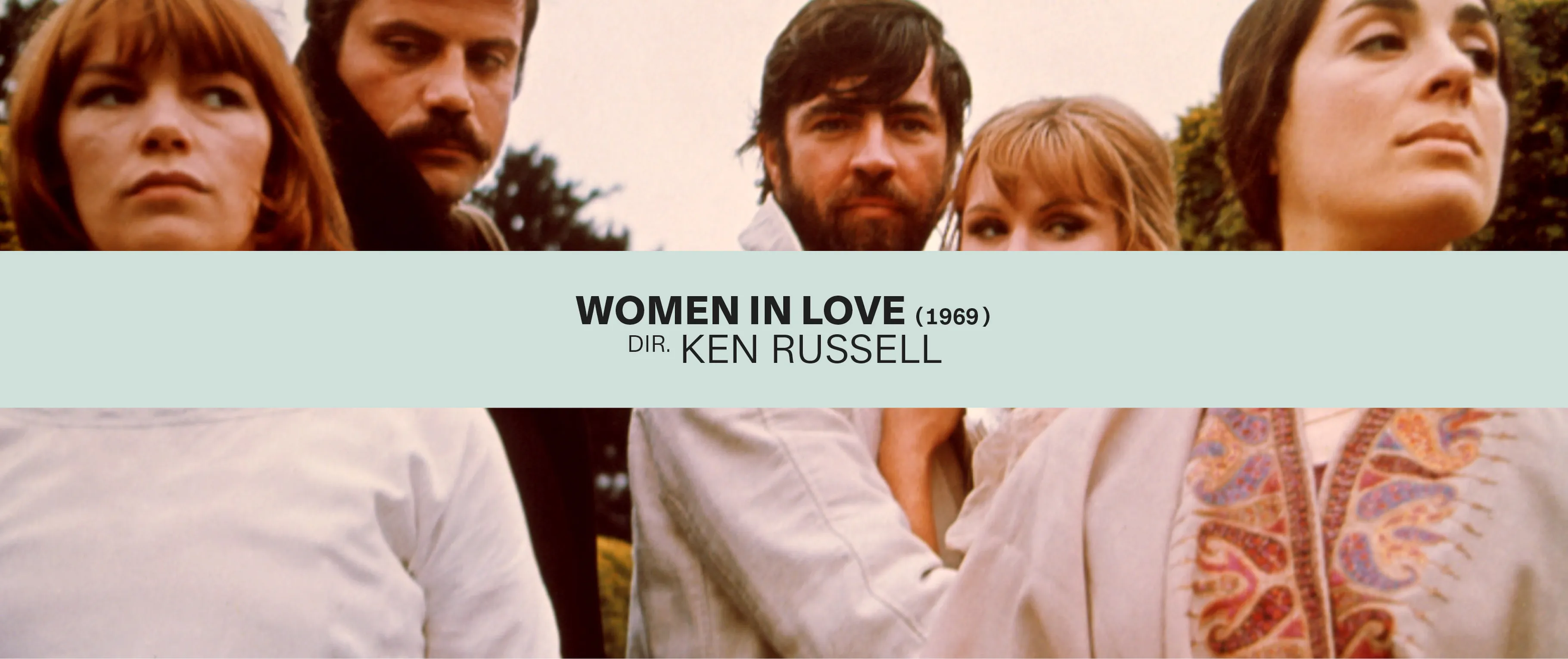

He was just finishing postproduction on the film that would bring him his first fame—his screen adaptation of the D.H. Lawrence novel Women in Love, directed by Ken Russell, which Larry not only produced but also penned the screenplay for. The film would be groundbreaking in its own right: The notoriously strict British movie censor would relent, as Larry described it to me, “on the showing of male genitalia…which we have in our famous wrestling scene.” In the film, actors Oliver Reed and Alan Bates are seen wrestling for several minutes, fully naked in a firelit living room. “Of course, this had never been done in cinema before,” said the film’s cinematographer Billy Williams. “They’re covered in sweat and the handheld camera is very fluid and is able to go with whatever movement, whatever happens.” Larry later said, in regard to his dealings with the censor, “When I think of the trouble we went through to see that the scene perfectly matched what went on in the book, including the patterns of wallpaper—and having to deal with this stuffy old man! He finally gave in.”

Women in Love premiered in London five months later, on Thursday, November 13, 1969 at the Prince Charles Theatre. It was an immediate commercial success, earning £6,735 in four days ($145,000 in today’s dollars). The fact that it was rated X—“Passed for Public Exhibition When No Children Under 16 Are Present”—likely improved its box office prospects. “Imagine your little boy being responsible for bringing this great classic to the screen. It’s a long way from Mount Rainier, isn’t it,” Larry wrote his mother, referring to the Maryland suburb where he grew up. In March 1970, the film opened in the United States with the wrestling scene intact. “All my friends have been seeing your film,” his mother wrote to him in June 1970, “and it has been fascinating to hear their comments. Everyone agrees that it is beautiful—the older ladies have reservations as to the sex portions of course.”

The same month Larry’s mother wrote that letter, the Christopher Street Gay Liberation Day march was held, commemorating the first anniversary of Stonewall. Stonewall was not yet Stonewall of today’s popular imagination: More of the public would have glimpsed homosexuality in the five-minute wrestling scene of Women in Love than in any reference to the raided gay bar in New York’s West Village. Larry’s own gay liberation was achieved through the making of that film, where the nude grappling of Reed and Bates surpassed the intensity of any of the heterosexual love scenes. In fact, Larry later decried the idea that Stonewall started the gay liberation movement. A year before his death at age 84 in 2020, he reflected, “Stonewall’s become like the Pilgrims. It was very important, but now it’s more of a myth than an actuality. There have been gay people in America since the very beginning. And we’re still being treated terribly.”

The title of Woman in Love is as deceptive—or deflective—in Larry’s film as it is in the original novel. It’s the story of two sisters, Gudrun and Ursula Brangwen (Glenda Jackson and Jennie Linden), but it is as much about the relationship between the two men they love as it is about the sisters’ love affairs with them. Audiences didn’t need the explicit wrestling scene to grasp that the relationship between the two male characters was at the heart of the movie. As it turned out, the film proved more timely than Larry could have imagined when he bought the rights to the novel. Many of the top-grossing films of 1969 and 1970 in the U.S. and the U.K. were also about male sexuality, male camaraderie and the love of men for one another—themes perhaps most famously explored in the Academy Award–winner Midnight Cowboy, about a male prostitute on the mean streets of New York and his street-smart amateur pimp. That film was directed by John Schlesinger, with whom Larry had a brief affair not long after he’d moved to London to work at Columbia Pictures in 1961, and like Women in Love, it had earned an X rating. Other male-philial films of the period include Robert Altman’s M*A*S*H, and George Roy Hill’s Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid. Larry would go on to be nominated for an Oscar for his screenplay of Women in Love. He lost to Ring Lardner Jr., for his adaptation of M*A*S*H.

At the end of July 1969, with post-production on Women in Love virtually finished, Larry began work on a screenplay for a film that he also wanted to direct: an adaptation of Yukio Mishima’s novel Forbidden Colors, about a renowned Japanese writer who becomes involved with an attractive and much younger man he meets on vacation. The novel, published in Japan in two parts in 1951 and 1953, was only translated into English in 1968. Larry switched the setting to England, the title to Head Games, and continued to work on it for more than two years. The amount of time he spent writing, rewriting and trying to sell the screenplay to a studio represented his own evolving and deepening commitment to coming out. In the end, the film was never produced, and financially the project had proven a waste of his time. But it wasn’t a failure. In those years, Larry had come to realize that committing himself to portraying openly gay stories was a key component of his own openness about his homosexuality. He wanted to make movies that pushed past old boundaries, and in doing so, push past the boundaries imposed upon him by his family, tradition, a decade of psychoanalysis—and by those who made the decisions about what kinds of movies get made. After the successful U.K. premiere of Women in Love, he wrote to John Van Eyssen, an old friend who was an executive at Columbia Pictures: “I think that what young audiences today respect more than anything else is honesty, and that is why Women in Love, Midnight Cowboy and Easy Rider are drawing them in: things are told quite frankly, without any attempt to add or cancel or make pretty or phony-up. Kids are sick of love scenes shot through gauze because they know that that is not the way it is in real life. They know that Ruby Keeler doesn’t dance on 42nd Street, but that Ratso Rizzo limps there instead.”

“I can let myself out of me through my writing. Use it. Use everything. Don’t be afraid.”

Larry didn’t want to see his own love scenes shot through gauze, and he was angry at the ways in which the movies were always ready to betray you if you believed too much in them. But his quest wasn’t simply about making movies that were sexually explicit. He wanted them to be well written, exquisitely produced and above all else, true to the rapidly changing world. Arguably, Larry never fully gave up belief in Hollywood romance: It had informed too much of his imaginative landscape while growing up watching the Hollywood films of the 1940s and ’50s at the theater near his house in Mount Rainier. As writer Edmund White, far from Larry’s most generous critic, would later say with a warm (if exasperated) sympathy, “People like Larry and me, who were raised on all the Hollywood movies, have a very romantic idea of love.” As a child, Larry’s father would get angry at him for the amount of time he spent at the movies, and that early conflict fed into his own later activism: “Daddy didn’t approve,” he recalled to me about his obsession with film. “I guess there was something unreal about it to him.” The injustice of his father’s reprimands never left him, and in recalling them, he himself was angry decades later. “I guess what motivates me is what is right and what is wrong,” he said. “It’s very black and white. It’s not complicated.”

By late 1970, it had become damningly clear that no studio was interested in buying a script about a gay writer in London, and thus Larry’s hopes to live as one were also dashed. He wanted to leave London, but he was afraid. As he wrote in his diary, he was frightened of New York, and “of freedom to enjoy myself there—sexually, without an analyst—in all ways”; he was frightened that the failure of Head Games left him without “a legitimate project (which for me means something I am doing for someone respectable—so I can hold my head up high) I am working on.” He was frightened of having a relationship—and of not having one. He then made a long list of the things that would be better about life in New York, including the ability to “come out of my shell.” Come out.

The last line of his London diary was written on November 18, 1970, almost exactly a year after the Women in Love premiere: He was 35 years old. “I am going back to NY to finally settle down and be gay. And it ain’t easy to do.” Two weeks later, on December 1, Larry Kramer moved to New York.

***

Oscar night 1971 was the high point of Larry’s film career. He had not expected to win—Glenda Jackson did win her first Oscar for Women in Love—and didn’t mind when he didn’t. He wrote a note to himself that he put into the pocket of his tuxedo: “I must remember that that picture would not be up there, giving pleasure to many if it were not for me—remember this was one of my reasons for going into films in the first place. I have made it possible to give pleasure to many, as Mother helped many with the Red Cross. I have kept up the family tradition. Writing is important, short stories and scripts and plays and maybe novels. I can let myself out of me through my writing. Use it. Use everything. Don’t be afraid.”

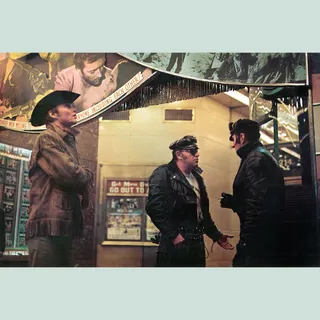

![]()

Midnight Cowboy, dir. John Schlesinger, 1969

![]()

Women in Love, dir. Ken Russell, 1969

Larry was not afraid. Over the next four decades, he wrote his first novel, Faggots; the plays The Normal Heart, Just Say No, and The Destiny of Me; Reports from the Holocaust: The Story of an AIDS Activist and The Tragedy of Today’s Gays; and the novel The American People, the second volume of which was published four months before he died. He also wrote two more screenplays. The first was for the 1973 musical version of Lost Horizon, produced by Ross Hunter, starring Liv Ullmann, among other nonsinging stars, one of the great fiascos and box office bombs of the decade—and the only thing Larry wrote that he was proud to say he regretted. The lucrative payday freed him to become the activist he was a decade later. He was one of the six co-founders of Gay Men’s Health Crisis in January 1982; and five years later, in March 1987, he gave an incendiary speech that led to the founding of ACT UP.

Nearly 30 years later, in May 2014, Ryan Murphy’s movie version of The Normal Heart premiered on HBO. It starred Julia Roberts, Mark Ruffalo, Jim Parsons, Joe Mantello and others. Larry adapted his play. It won an Emmy for Outstanding Television Movie. Larry was frail, and he leaned on Ryan Murphy’s arm as they went to the stage, with the cast and producers, to accept the award. The audience stood for a long ovation.

“We’re only here because of one person,” Murphy said, “and that’s Mr. Larry Kramer. We did this for him.… We’re going to use the rest of our time,” he added, “to ask young people watching to become Larry Kramers, to find a cause you believe in that you will fight for, that you will die for.”