Everybody's Talkin'

By Andrew Male

Midnight Cowboy, dir. John Schlesinger, 1969

Everybody’s Talkin’

How Harry Nilsson’s sunny tune—and the tonal contrasts of the Midnight Cowboy soundtrack—amplifies the story’s emotional discord

By Andrew Male

June 18, 2024

Some time in September 1968, Bob Dylan showed up at the New York apartment of film producer Jerome Hellman, looking to beguile him with a song. Hellman was working with director John Schlesinger on the movie adaptation of Midnight Cowboy, James Leo Herlihy’s 1965 novel about a naive Texan dreamer, Joe Buck, who moves to New York to become a high-class gigolo, only to fall in with a disabled con man, Enrico “Ratso” Rizzo.

![]()

Brenda Vaccaro and Jon Voight in Midnight Cowboy

![]()

Dustin Hoffman in Midnight Cowboy

Schlesinger and Hellman were still tangled up in editing and reshoots and looking for a title song, one that would comment on and underscore the themes of the film in much the same way that Simon & Garfunkel’s “Mrs. Robinson” had transformed Mike Nichols’s The Graduate a year earlier.

Dylan played Hellman an unfinished sketch, probably “Lay Lady Lay,” and it’s interesting to consider how the laid-back rhythms and seductive lyrics of that finished song (“Whatever colors you have in your mind / I’ll show them to you and you’ll see them shine”) would have changed the mood and the meaning of Schlesinger’s film. But it was not to be.

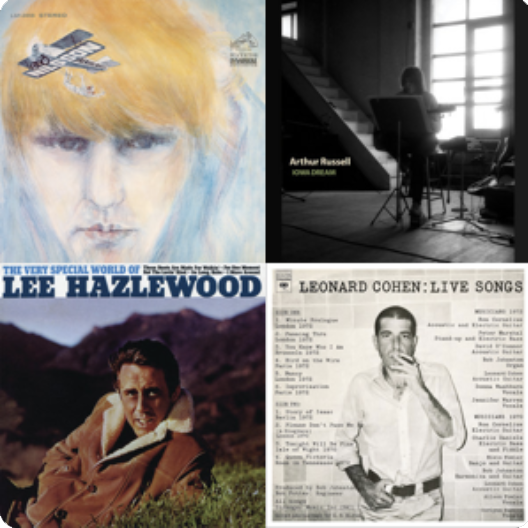

As the story goes, Dylan failed to complete the song in time for inclusion. According to Glenn Frankel’s 2021 making-of book, Shooting Midnight Cowboy, other songs that got rejected around that time include Leonard Cohen’s “Bird on the Wire” and Joni Mitchell’s “Midnight Cowboy” (“too literal,” said Schlesinger). In the end, Schlesinger and Hellman returned to the song they’d been using as the temporary track to help guide and pace the editing of the film’s opening sequence, Harry Nilsson’s 1968 cover of Fred Neil’s “Everybody’s Talkin’.”

Midnight Cowboy playlist by Galerie

“…there is a disconnect between how it sounds and the world and the people it’s paired with.”

It’s now hard to imagine any other song existing in Nilsson’s place. Lyrically, “Everybody’s Talkin’” might seem an incongruous (even ironic) choice, Neil’s paean to escape from city bustle—recorded in one take by a singer anxious to leave New York and return home to Miami—now soundtracking an opening sequence in which Joe Buck (Jon Voight) dons his hustler attire of black Stetson, green Western shirt, tight pants, fringed suede jacket and black-and-metallic cowboy boots to quit the wide-open plains of Texas for the urban claustrophobia of Manhattan.

But sonically the dappled rhythms of Al Casey’s guitar, Jim Gordon’s cantering drums and Larry Knechtel’s walking bass possess a bright forward momentum, while Nilsson’s “wah-wah-wah” scat singing calls to mind the relaxed trainyard yodel of “The Singing Brakeman” Jimmie Rodgers.

The vibe is positive, optimistic and Western-themed, utterly in tune with Joe Buck’s misguided mindset. He thinks he’s going to succeed in his new career in a new town, and Nilsson’s song—classic country by way of contemporary pop—allows us to feel the same way, however briefly.

The song also pointed the way for how Schlesinger wanted the whole film score to feel: “totally different-sounding from the usual things at the time.” Following the example of The Graduate, the director sought a music supervisor who was more than just a film composer, someone who “was a coordinator of popular songs—someone who wasn’t necessarily going to compose.” He called for John Barry.

By 1968 John Barry was a composer in demand. British, classically trained, tall, slim and suave, Barry had already made a name for himself with the James Bond soundtracks and had proved he could move effortlessly from dramatic bombast to a kind of delicate melancholy, adding an interior life to the Secret Intelligence Service agent that wasn’t always present in the scripts or performances. He’d also shown, in films such as 1964’s Seance on a Wet Afternoon and 1965’s The Ipcress File, an ability to look outside the usual orchestral repertoire, employing such distinctive-sounding instruments as vibraphone and cimbalom in a pointedly minimalist setting.

In an unlikely move for a newly appointed composer, Barry insisted that Schlesinger keep Nilsson’s “Everybody’s Talkin’” as the film’s opening theme and proceeded to work closely with the singer on a series of re-recorded versions of the song that would reappear at various points through the film. The idea is perfect, allowing the voice of Nilsson, especially that “wah-wah-wah” refrain, to operate as Joe Buck’s interior mantra, a soothing callback to the optimism of that opening scene, reinvoked when times are bad. Arguably, Barry heard in Nilsson’s vocal refrain the keening echo of a mouth-organ and references that in the film’s alternate theme. Combining Toots Thielemans’s yearning harmonica with a “Tumbling Tumbleweeds”–style walking bass, mournful string section and that Spanish guitar, “Theme from Midnight Cowboy” and the more elegiac “Joe Buck Rides Again” could have come from a forlorn score to some forgotten John Ford Western about weariness and failure. They’re pieces of music weighted with a plains-wide sadness that manage to convey the loneliness and delusion at the heart of the film, something Barry saw in 1960s New York itself.

“You drive through New York City’s bad streets and you see these guys walking around,” Barry told biographer Eddi Fiegel, “and there’s this terrific sadness in the air.… That harmonica theme was the soul of that character.”

This is exactly what Schlesinger and his scriptwriter Waldo Salt had hoped for. The film’s use of overlapping sound and image, gauzy flashbacks and black-and-white dream sequences, along with the snatches of TV adverts and radio talk shows we see and hear throughout the film, are all intended to allow us a glimpse of Joe’s own damaged soul. It’s an outsider’s vision of an unfriendly New York created by a House Un-American Activities Committee–blacklisted, Chicago-born scriptwriter, a London-born director and a composer from the ceremonial English county of North Yorkshire.

![]()

Harry Nilsson's 1969 rerelease of "Everybody's Talkin'"

![]()

Dustin Hoffman as Ratso Rizzo

However, in addition to Joe Buck, Barry also created an interior soundtrack for another outsider, Dustin Hoffman’s Ratso Rizzo, the disabled con man dying from a respiratory illness, shunned by all the downtown hustlers and hipsters and dreaming of escaping to Miami. That escape is soundtracked with the dancing comic samba of “Florida Fantasy.” The expert touch here is in making Rizzo’s theme resemble an advertising jingle, similar to those he listens to on Joe Buck’s transistor radio, specifically the Florida Citrus Commission jingle (“Orange juice on ice is nice!”) that the duo dance to while freezing in their derelict New York tenement. Both character themes are comically upbeat, tunes that only serve to underscore the dire outsider existence of the lives they are soundtracking.

Barry’s selection of pop songs for the rest of the score are also outsider choices. Would Midnight Cowboy have been a better film if the bands soundtracking the rest of the film had been drawn from the hip psychedelia of 1967 (Jefferson Airplane, the Doors, Pink Floyd, etc.)? Would that extended Warhol-style party scene that Joe and Rizzo attend toward the end of the film have been improved if accompanied by the Velvet Underground?

In choosing songs by West Coast harmony-pop outfit the Groop (“A Famous Myth,” “Tears and Joys”), NYC art-rock collective Elephant’s Memory (“Old Man Willow”) and an early track by L.A. singer-songwriter Warren Zevon (sung by session vocalist Lesley Miller), Barry created a soundtrack that still feels unique to Midnight Cowboy. These are songs that have not been ruined by overfamiliarity or a life outside of the film. The Groop songs are imbued with a pop naivete that chimes with Joe Buck’s innocence, while the Elephant’s Memory tracks (especially the remarkable “Old Man Willow”) possess an uncanny otherworldliness, existing at one remove from the contemporary New York they are soundtracking. They are exclusive to Midnight Cowboy and the subjective vision of Joe Buck and, like him, they don’t quite fit. Like nearly all the music chosen for Midnight Cowboy, there is a disconnect between how it sounds and the world and the people it’s paired with.

![]()

Jon Voight in Midnight Cowboy

![]()

Dustin Hoffman in Midnight Cowboy

Which perhaps explains why, when Barry returns to Harry Nilsson’s “Everybody’s Talkin’” at the end of the film to accompany Joe and Ratso’s escape by bus to Florida, it feels so right, so joyous. That dissonance in its optimistic lyrics, which seemed to define this emotionally disjointed character, finally makes perfect, melancholy sense (“I’m going where the sun keeps shining”). Even if we know Ratso is dying and will never make it to his final destination, there is the feeling that Joe Buck, newly attired in a short-sleeved cream cotton shirt, dark slacks and black loafers, has finally arrived somewhere where the weather suits his clothes.