The Glass Effect

By Stephen Dalton

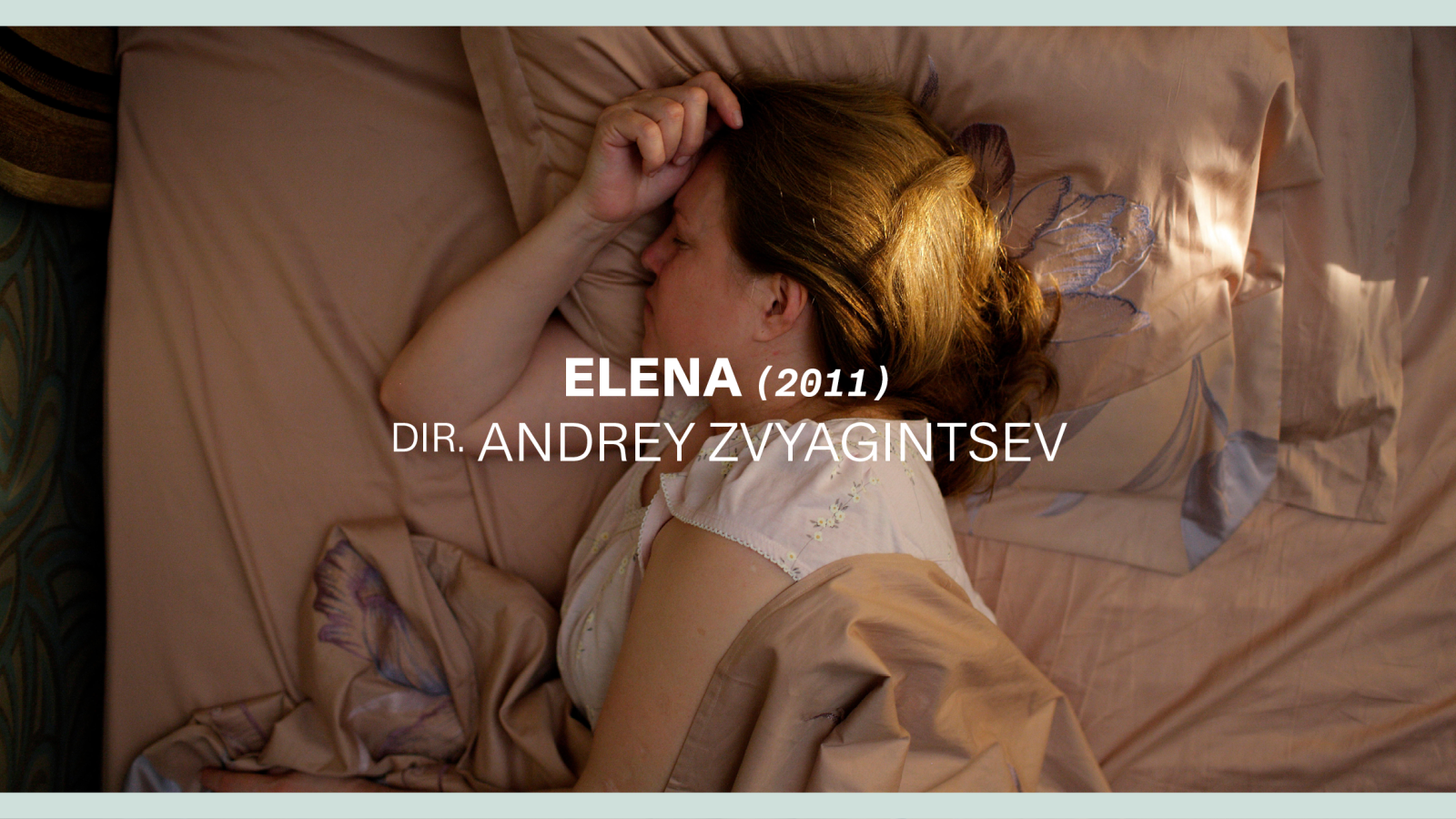

Elena, dir. Andrey Zvyagintsev, 2011

The Glass Effect

How Philip Glass’s monumental scores conjure a cathedral of sound with cinematic purpose

By Stephen Dalton

September 15, 2023

Director Andrey Zvyagintsev’s elegantly low-key 2011 thriller Elena is a very Russian tragedy. An existential tale of crime without punishment, it feels like a Dostoyevsky story updated for a godless age. Nadezhda Markina gives a quietly devastating performance as the eponymous antiheroine, a middle-aged nurse forced into a desperate moral dilemma: She must sacrifice her rich husband to help out her feckless son, who urgently needs bribe money to save his own delinquent teenage son from military service. There is no hint of redemption in this powerful, purgatorial drama.

Zvyagintsev is renowned for his forensic dissections of Putin-era society, notably The Return (2003) and Leviathan (2014). He insists Elena is more universal than specific, but the film has special resonance in post-Soviet Russia, with its glaring inequality and widespread corruption. Despite its noirish thriller elements, Elena is striking for its tonal control, especially its spare use of music. The third movement of Philip Glass’s Symphony no. 3 serves as a recurring motif during key transitional scenes as Elena travels between different social spheres, between inner-city luxury and bleak industrial suburb, between devoted wife and killer. Glass actually offered to compose an original score, but Zvyagintsev felt this preexisting piece was already picture-perfect. Indeed, with its quiet accumulation of creeping dread and growing sense of momentum toward inevitable tragedy, this music seems to mirror Elena’s inner psychodrama with uncanny accuracy.

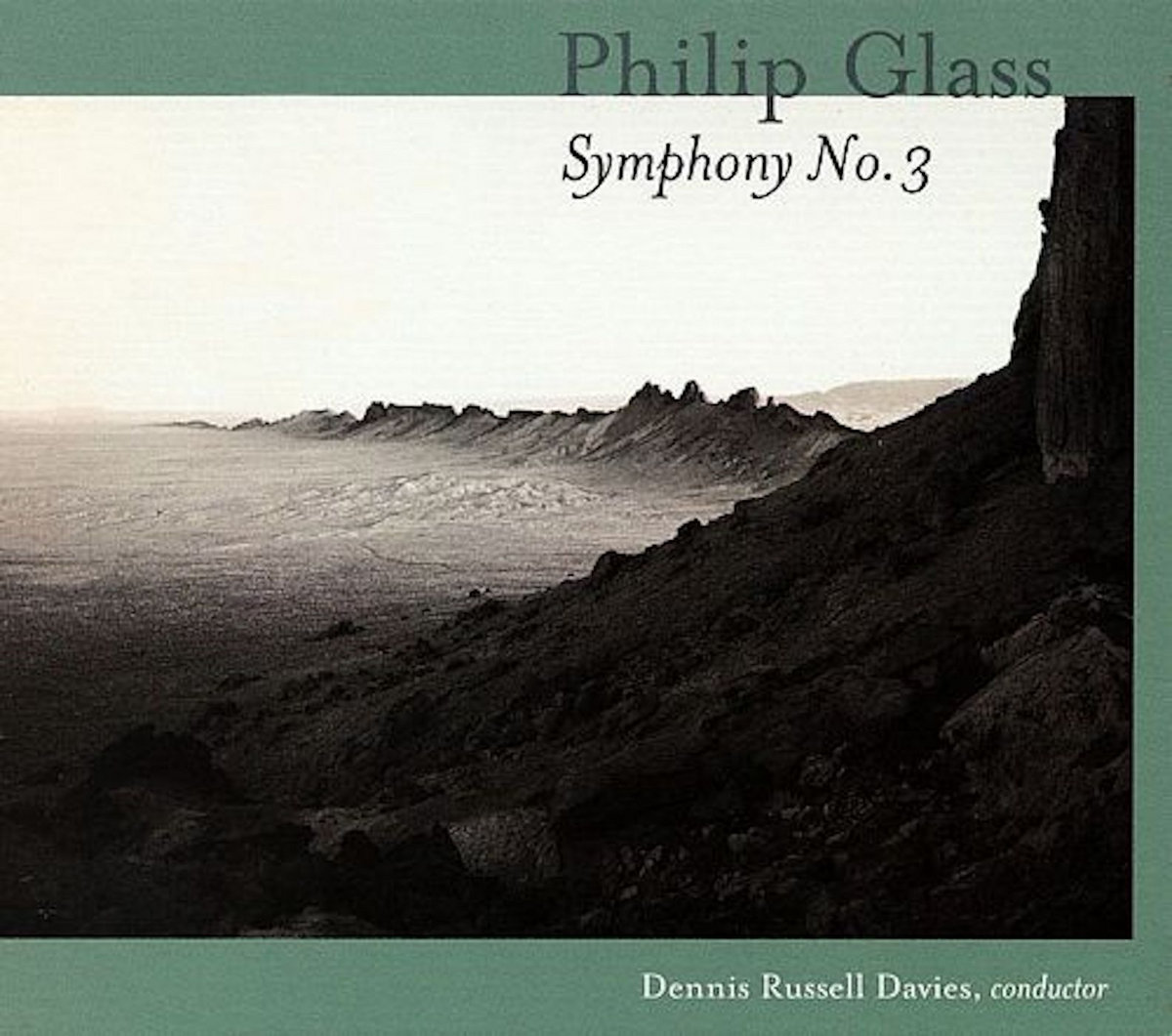

Symphony no. 3 was commissioned and first performed by the Stuttgart Chamber Orchestra in 1995. The third movement is based on a chaconne, a repeated harmony sequence popular as a dance form in Europe during the Baroque period. Glass’s piece opens with chilly precision, just seven cello and viola players, gradually swelling and deepening until all 19 ensemble members are on board. Holding back the full version until the final credits, Zvyagintsev mainly uses the austere first half, reinforcing the sense that Elena takes place in a morally and spiritually impoverished hellscape.

Philip Glass: Symphony No.3

Elena is one of more than 90 film credits for Glass, though his score work is actually more like a second career. The Baltimore-born, New York–based composer’s roots lie in experimental orchestral music and avant-garde opera, and he retains a strong hint of this modernist rigor in his cinema work. In the 1960s, he studied in Paris under Nadia Boulanger—that famously exacting grande dame of music teachers—then in India under Ravi Shankar. “One taught through fear, one through love,” he would later recall. This broad musical grounding led him to fuse Western and non-Western traditions into his signature style. Alongside composers including Steve Reich, Terry Riley and John Adams, Glass was hailed as an early pioneer of minimalism, although he now rejects that term as outdated and inaccurate.

Filmmakers seeking “the Glass effect” know what they are getting: arpeggiated repetitions, pulsing rhythms, radiant woodwind fanfares, glistening strings, cascading piano motifs, plus strong use of percussion, compound meter and triple-note clusters. But despite these instantly recognizable elements, Glass scores are remarkably varied and versatile. Some are chilly and cerebral, others lush and romantic. They can have a dramaturgical function, shaping and propelling the narrative, or a more transcendent spiritual dimension, liturgical and hypnotic—sacred music in a secular era.

Composing for opera, stage and ballet taught Glass that scoring is a collaborative art form, a common attitude in theater but unusual in cinema. Many of his most feted scores grew from mutual creative decisions between composer and filmmaker that began before or during production. Glass views music as a primary element in filmmaking, on a par with cinematography, yet complains that it is too often relegated to a last-minute addition. “Those who treat music as an afterthought have lost a powerful artistic ally,” he told Charles Merrell Berg of the University of Kansas in 1987.

“... A MORE TRANSCENDENT SPIRITUAL DIMENSION, LITURGICAL AND HYPNOTIC—SACRED MUSIC IN A SECULAR ERA.”

.png)

Glass composed some of his best-known early scores in close collaboration with experimental documentary directors, notably Godfrey Reggio on his mesmerizing audiovisual symphonies of modern society in freefall: Koyaanisqatsi (1982), Powaqqatsi (1988) and Naqoyqatsi (2002). The film titles are taken from the Native American Hopi language, and Glass consulted with Hopi tribe members to check that his musical inflections were as authentic as possible.

Documentary filmmaker Errol Morris, a musician himself, is another longtime Glass collaborator, working with him on The Thin Blue Line (1988), A Brief History of Time (1991) and The Fog of War (2003). Glass draws a distinction between how music functions in drama and nonfiction films. “We can be more experimental with documentaries than I can be with narrative films,” he said in a 2006 interview for Soundtrack.Net. “There’s much more room and fluidity.”

With his propulsive, gleaming, vivid score for Paul Schrader’s Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters (1985), Glass achieved a rare harmony between musical and dramatic effect, mirroring the hurtling, self-destructive mania of doomed Japanese cult author Yukio Mishima. He then began to develop a tentative relationship with more mainstream dramatic cinema.

In choosing film-score projects, Glass has claimed subject matter is less important than the director, team and working conditions. That said, as a practicing Buddhist, he was a natural fit for Kundun (1997), Martin Scorsese’s biopic about the young Dalai Lama’s flight from Tibet following the Chinese invasion. A chiming, shimmering synthesis of traditional Tibetan instrumentation with the composer’s signature electro-orchestral style, this lustrous score achieved a kind of transcendent spiritual dimension in the ears of some critics.

From left: Kundun, dir. Martin Scorsese, 1997; Powaqqatsi, dir. Godfrey Reggio, 1988; Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters, dir. Paul Schrader, 1985

Kundun earned Glass his first Oscar nomination, opening the door to a fertile period of high-profile scores, many based on repurposed older pieces. All composers recycle ideas, of course, from Bach to Bowie and beyond. But Glass has the advantage of an usually prolific pool of work to draw from, including operas, ballets, symphonies and genre-spanning collaborations in the rock and pop world. Winning a Golden Globe for Glass and his co-composer Burkhard Dallwitz, Peter Weir’s darkly satirical sci-fi fable The Truman Show (1998) features new compositions like the cascading piano lullaby “Truman Sleeps,” alongside pieces from previous Glass film scores, notably Mishima and Powaqqatsi.

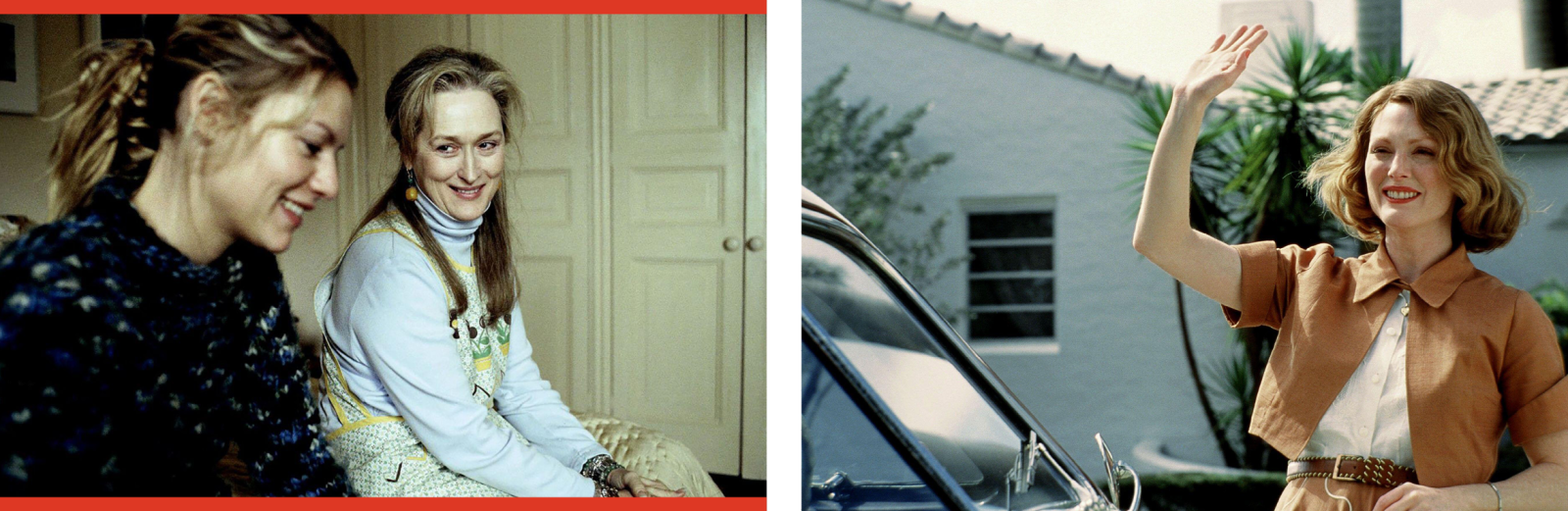

Stephen Daldry’s elegant ensemble piece The Hours (2002) showcases a more exacting kind of recycling as Glass adapts and rearranges older compositions into new shapes. Alongside new material, like the film’s spine-tingling piano-led main theme, the lean vocal number “Protest,” from his 1979 opera Satyagraha, is reborn as the more sumptuously arranged instrumental “I’m Going to Make a Cake.” Likewise, the Kafka-inspired solo piano piece “Metamorphosis Two” is reworked into the more wintry, lushly upholstered “Escape!” In dramatic terms, the Glass effect works as a kind of musical glue here, lending coherence and consistency to a time-jumping, multi-character narrative. Daldry claimed the score served as “another stream of consciousness, another character.”

Changes of genre, visual grammar and cultural context alter the impact of a piece of Glass music, even if the composition itself remains intact. Two years before Elena, sections of Symphony no. 3 appeared on the score to Transcendent Man (2009), Robert Barry Ptolemy’s documentary about author and futurologist Ray Kurzweil. It forms part of a Glass mixtape that includes new compositions alongside extracts from previous film scores. Where Zvyagintsev heard fatalistic despair and Dostoyevskian darkness in these prowling string motifs, Ptolemy uses them to invoke questing intellectual curiosity.

The Hours, dir. Stephen Daldry, 2002

In recent years, the Glass effect has become associated with somber, frosty, noir-tinged psychodrama. Two of his more notable later scores include Richard Eyre’s crisp literary adaptation Notes on a Scandal (2006), starring Cate Blanchett and Judi Dench, which earned Glass his third Oscar nomination, and Woody Allen’s humdrum murder thriller Cassandra’s Dream (2007), which co-stars Ewan McGregor and Colin Farrell. Both films are exercises in uneasy listening, with hints of Bernard Herrmann’s legendary collaborations with Alfred Hitchcock.

But Glass himself is far removed from his gloomy, professional image. He is wry and witty in interviews, relishing jokes about his repetitive signature style. He recently observed that his harshest early critics no longer trouble him, chiefly because they are dead. “You outlive them, if you’re lucky,” he told The Guardian in 2017. “The battle was never won or lost. The army just went away.”

The playful side of Glass certainly comes through in his 1998 re-score of Tod Browning’s vintage horror classic Dracula (1931). Written for himself to perform with longtime collaborators the Kronos Quartet, it has become one of his most enduring and frequently programmed pieces. Instead of opting for full-blooded gothic effect, Glass teases out the film’s humor alongside the horror, with public screenings often accompanied by laughter.

Dracula is a great example of how the Glass effect can transform and elevate a film, smoothing out some abrupt scene changes and softening its rushed ending. “It’s the perfect collaboration,” Glass joked in promotional interviews for a 2010 French festival performance. “The director’s dead, the writer’s dead, every actor in the movie is dead. The only one left alive is the composer, who wasn’t born when it was made! Ideal.”

Zvyagintsev considers Glass “the greatest composer of our time.” After Elena, he borrowed preexisting Glass pieces again for his scouringly bleak, quasi-Biblical parable Leviathan (2014), bookending the film with radiant passages from the 1983 opera Akhnaten. Using devotional religious music for a prizewinning, Oscar-nominated film that involves church corruption was another inspired masterstroke. For Zvyagintsev, as for so many filmmakers, the Glass effect means a sublime fusion of sound and image. “I want him to know how grateful I am for his work,” the director told PopMatters in 2015, “because he truly elevated my film with his music.”