Pixar's Unlikely Rival

By Kaleem Aftab

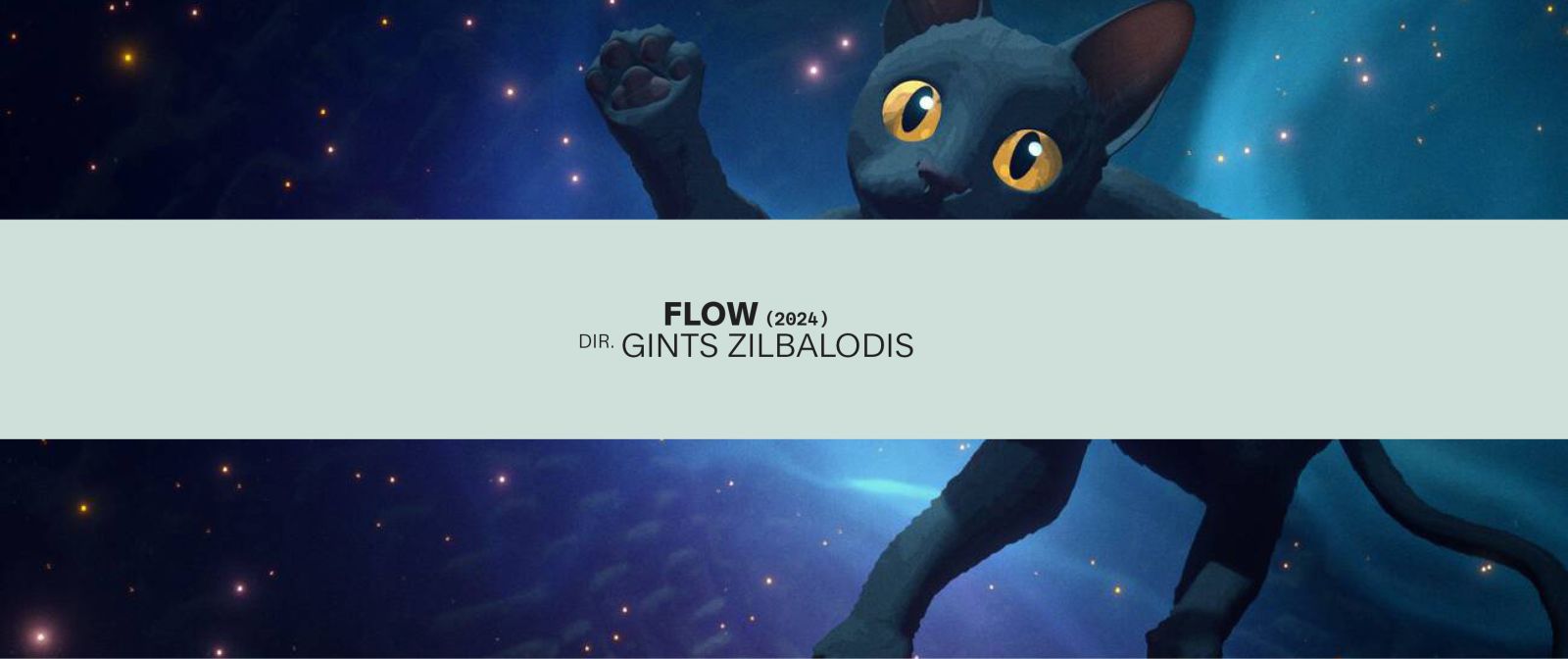

Flow, dir. Gints Zilbalodis, 2024

Pixar’s Unlikely Rival

Flow director Gints Zilbalodis on how his indie animation about a refugee cat conquered the world

By Kaleem Aftab

February 19, 2025

Flow is so popular in Latvia that a statue of the gray kitten at the heart of the story has already appeared in the country’s capital, Riga. It hasn’t even been a year since the animation first appeared at the Cannes Film Festival, but the cat—and the movie—have already become a badge of national pride, alongside its remarkable director Gints Zilbalodis. In only his second film, Zilbalodis has been ripping up the rule book for how to make successful animation. After taking home the Golden Globe for Best Animated Motion Picture, Flow went on to earn two Academy Award nominations. Remarkably, Zilbalodis is largely self-taught and made Flow for a fraction of the cost of a Pixar animated film.

The story of a water-fearing cat who escapes a flood by seeking refuge on a boat filled with a myriad of species doubles as an allegory about the environmental destruction humans have unleashed on our planet. Flow’s celebration of collective power and friendship overcoming insurmountable odds is also technically brilliant, with the director positioning cameras using Blender and sending pre-animated shots to a team of animators, who fleshed out the images into spectacular 3D.

Shortly before winning this year’s Oscar for Best Animated Feature, director Zilbalodis met with Galerie to discuss the philosophy behind Flow and why doing things his own way unexpectedly made him a better team player.

From left: a flooded cityscape in Flow; the feline protagonist

Congratulations on the success of the film debuting at Cannes, winning a ton of awards, and now the two Academy Award nominations. Can you describe the experience?

Yes. It’s been an incredible journey with this film. It’s the first time a film from Latvia has ever been nominated for either a Golden Globe or an Oscar, and then it also won the Globe. So there’s a lot of excitement back home in Latvia. And it’s also not just for Latvia but also for the whole independent animation scene. It’s the first time a small, independent film has won a Globe for Best Animated Feature, and that is very exciting for animators everywhere.

That idea of supporting communities is also at the heart of Flow. By showing animals in a world that humans seem to have left behind, the film suggests that human life on Earth is fragile and possibly on the brink of extinction. Can you explain why you wanted to depict such a world?

From the beginning I had the idea of making a film with no dialogue, and depicting humans in this story would have required us to have them speak, and I really didn’t want to do that. I set my heart on telling the story visually, using images, music and sounds. We tell the story from a cat’s point of view and through some other animals. I wanted these animals to behave like real animals instead of anthropomorphically, where they would be walking on two legs and telling jokes, which we might have seen in other animated movies. I think real animals are a lot more interesting than that! Their natural behavior and tendencies can be so interesting and funny that we are able to relate to them. We recognize moments of fear or joy, along with the relationships that animals have with each other. Seeing the world from the point of view of an animal because of their innocence makes it a lot more intense, emotional and impactful.

But it’s also a world in which we see man-made buildings and paraphernalia. It’s an amazing balance that you create between the animal kingdom and us.

We see some buildings, monuments and landmarks that humans have left behind, but these human constructions do not explain everything. We left some clues in the environment for you to consider what might have happened, but I think it’s a lot more cinematic and visually interesting to have this kind of mystery, for you to participate in the story rather than explain everything with words.

Cats seem to have become so popular in the media in recent years, or maybe it seems like that because of all the cat memes on the internet and the success of video games like Stray. What was your motivation for having a cat as the most prominent animal in Flow?

It all started with the idea of the cat and its fear of water, because that’s something I think people understand, that cats don’t like water, which gave me an opportunity to not have a character as an antagonist. It’s really a cat-versus-nature story, which to me is more interesting because it gave me the opportunity to make every character in the story both good and bad. There is no simple hero or villain. Having the flood and something from nature as the obstacle allows us to really flesh out the characters more. Another reason for the cat is that this is the first film where I’ve worked with an animation team. On my previous films, I worked entirely on my own, including my first feature, Away. Flow is a story about a character who must trust others and work together, so I thought a cat would be a great protagonist because cats are very independent. They’re not group animals like dogs are. It’s a great starting point for this independent cat to go on a journey and learn to trust others.

In fact one of the many beautiful things in this film is how you explode the stereotype of certain animals. What was the idea behind this?

We have five main characters, and each of them starts out almost as an archetype of what we imagine these animals would do. The cat is independent and grumpy and wants to do things its own way. The dog is very friendly, always following a group and looking for someone to tell it what to do. So basically, they’re opposites. Throughout the journey, the cat learns to trust others and collaborate, while the dog ends up being more independent. The cat and the dog are inspired by real cats and dogs I’ve had in my life growing up. There’s also the bird—we needed a very big bird because in one of the scenes, the bird grabs the cat and they fly up into the sky. So we settled on a secretary bird, which is from South Africa, and this character needed to have a very majestic presence and be very charismatic, because it’s the leader of the boat. Meanwhile, the lemur thinks others will like it because it is obsessed with objects. So basically, all of these characters are looking for the same thing. They’re looking for a group and have different ways of doing that.

When there is no dialogue, what are the elements you need to think about to tell the story visually?

You need to make it very clear what is going on. For example, the characters have to have clear goals. The cat is trying to get to these giant cliff towers to be able to escape from the flood, which is easy to follow. The other characters, such as the bird and the lemur, also have their own obsessions. You need to have a simple backbone that sustains people’s interest and is understandable while also creating an impactful plot with a lot of characters and plot twists. Combining those two elements is hard. Simplicity is deceptively complicated! It has to be simple but not simplistic. There are ideas and emotions that have to be conveyed without dialogue, and so the other tools at our disposal become more important—the music, sound, animation and cinematography must have a much bigger role than in a typical film. So this is why I always stress that Flow is a dialogue-free film and not a silent film, because sound and music play such an important role, allowing us to tell the story and convey what the characters are feeling. The camera becomes a very active participant.

Stills from Flow

“We were not trying to copy the big studios. We’re trying to find our own way and make something unique and different.”

It feels strange to talk about animation in terms of camera position, when there is no film set or physical camera in the making of this movie. Can you explain how you ensured the camera becomes an active participant?

Usually, animated films are drawn with storyboards, but I didn’t use storyboards when making this film. I designed the scenes directly in a 3D program where I could discover ideas by looking around and exploring the sets. This creates something more organic and less rigid than most animations. I wanted to do that because the camera is moving a lot and there are some very long shots, going on for five minutes, and because the constant movement is simply impossible to draw. So I was obliged to use that technique. The camera is not moving because it looks cool or just to show off; it’s really there to tell the story and get us more immersed in this world and be more intimate with the characters, getting very close to them and experiencing what they experience.

When you made your first feature, Away, you were very much a one-man band using these techniques. In this film you have something like five credits, and you also worked on the music. Can you talk about the process in 3D? Could I make an animation film at home?

Well, I basically create an environment that is not yet finished. It’s just a sketch of the environment, which is not filled with details, so I can quickly make adjustments. I can take this virtual camera, walk around and find ideas, almost like a live-action director would arrive on set with a viewfinder and look around. I place characters in the environment, but they are not animated. It looks kind of silly. They’re basically floating through the environment. But it’s my way of finding ideas very quickly, where I can try out alternative ideas and put lights in a scene to influence how I can film it, and where I place the camera. I can already see some effects, like very rough estimates of water or fog, which also helps me to understand it. To get these ideas, I need to see it. I’m not like other filmmakers, who can imagine everything in their heads, see it very clearly, and then they can describe to their crew what they want. I work differently. I have to try different things and eventually discover what I want, and then I can show this version to the crew, and this rough program can explain a lot more what I want than I could with words.

And when do you add the music?

I make the music really early and lay down music ideas at this early stage. I work on the music while I’m still writing the script, and it influences how the story develops. I get ideas for what might happen to the characters, so I can already edit the film using my own music, instead of what is typically done in the industry, where you take music from other films in the editing and then you ask a composer to make something similar. Instead, I edit to my music, and later we polish it. I just started working this way with Away. I didn’t really study music, and I don’t play an instrument or read sheet music, so I just write the music electronically on my laptop. But after I’d done the first edit, we brought on another composer, Rihards Zaļupe, who is also from Latvia, who is a lot more experienced than me, and he would really help with the orchestration and make sure that all the multiple layers to the music worked correctly. I didn’t want a traditional score that sounded like you had heard it before, so we also used some electronic instruments, an analog synthesizer, mixed with some unconventional instruments, like glasses of water where we would use our fingers to make sounds.

Away, dir. Gints Zilbalodis, 2019

That’s very innovative. Likewise, you didn’t go to film school, so how did you come to draw and make animation movies?

I just learned by making a bunch of films. I started by making hand-drawn animated films, including a short I made in high school about a cat who was afraid of water, which I then adapted into Flow. But after making that, I decided to focus on 3D animation, where I model things instead of drawing them. It’s more like sculpting because, actually, I’m not that good at drawing. I studied drawing and painting, but maybe I’m better at painting. I went to an art high school and made films in my free time. Some of them were shown in festivals where I won some awards, which allowed me to fund my next films. So instead of going to a university or an animation school, I made a bunch of short films. I made my first feature film using the same kind of method, which was basically funded as multiple short films. That was my film school. I had always hoped to eventually work with a team, but having done these tasks myself helped me to understand what all these people do and understand their language. I just learn better by making things rather than, like, studying theory.

How did those experiences help with Flow?

I’m still learning. With Flow I learned how to work with the team. When I work alone, I don’t need to explain what I want. But this time I had to find ways to convey my ideas with words. Maybe I was a filmmaker before, but now I was directing, which was a new experience and challenge for me. Since I hadn’t gone through the system, maybe I discovered new ways of solving certain problems. And I think that’s part of the appeal of the film and what made it special: We were not trying to copy the big studios. We’re trying to find our own way and make something unique and different.