Power Dressing with Pam Grier

By Cintra Wilson

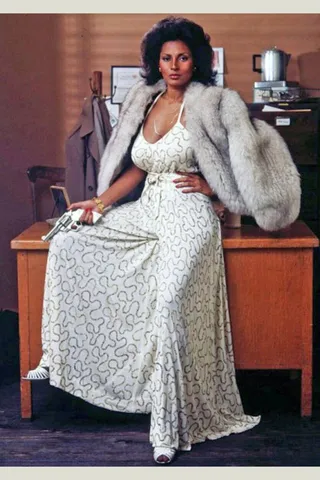

Coffy, dir. Jack Hill, 1973

Power Dressing with Pam Grier

cIntra wilson

From Foxy Brown to Jackie Brown, the dominant glamour of a screen legend

September 13, 2024

![]()

Sheba, Baby, dir. William Girdler, 1975

![]()

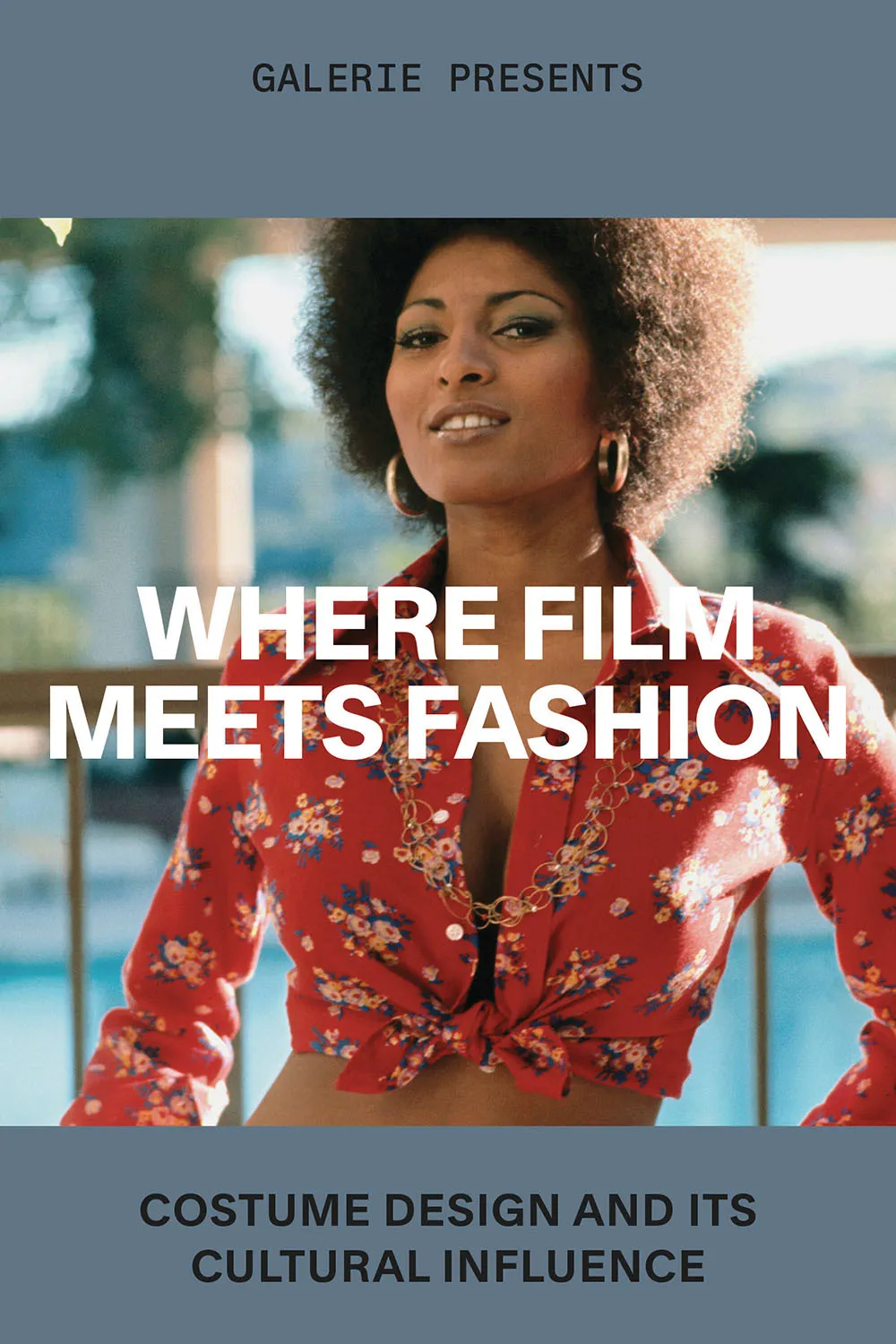

Pam Grier as Coffy

“She swaggered into the room all fire and ice, wearing black hip boots, hot pants, and a blouse stretched dangerously over her breasts. In one hand she carried a bullwhip, in the other a sawed-off shotgun. Snarling out of a corner of her crimsoned mouth, she commanded: “All right, chauvinist hog, on your knees!” As the cringing male slowly sank to the floor before her, she let the shotgun slip from her arm and in the same deft move administered a karate chop somewhere below his waist, rendering him sterile forever.”

— Louie Robinson, “Pam Grier: More Than Just a Sex Symbol,” Ebony, June 1976

When Pamela Suzette Grier was born in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, in 1949 to a nurse and an airplane mechanic in the Air Force, little did anyone suspect that she would become a screen goddess with an acting career spanning more than 50 years, a timeless symbol of feminine badassness for women of all colors and an enduring style icon through some of the most treacherous fashion decades in history.

Costume designers have walked an interesting tightrope with Ms. Grier. In virtually every notable film of hers, the actor’s outfits, while outwardly glamorous and sexy, have needed to serve her characters’ abilities to burst into sudden violence. Her look—arguably the original athleisure—has always been both ready for karate or to turn every head at the Hyatt Regency bar. Even in cuts and synthetic fabrics as radical as those of the 1970s, Pam Grier manages to look timeless, even regal. She was a different kind of beauty icon, one who would cut your head back to the fat meat if you messed with her. The arrival of Grier provided a new role model: a woman who refused to be victimized—by any means necessary.

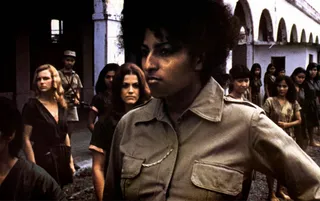

At the beginning of her career, there was something about Grier’s take-no-prisoners command presence and her singular, Cleopatra-esque beauty—her aquiline nose; her long, curvaceous body; her velvety skin; and the fact that she had a fast and powerful mouth on her—that gave Hollywood development executives a somewhat pervy desire to see her behind bars. This kept her busy shooting prison movies in the early 1970s. The young Grier inspired visions of an untamed, dangerous wild woman, a conceit that led her on several occasions to the Philippines, where producer Roger Corman’s movie sets kept comely incarcerated women in torn T-shirts in bamboo cages, tortured them on Catherine wheels, shot them with fire hoses and mercilessly threw them in the hole.

![]()

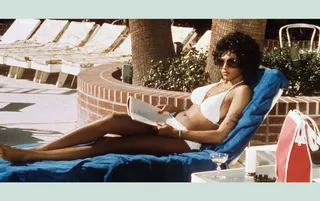

A poolside look in Coffy

![]()

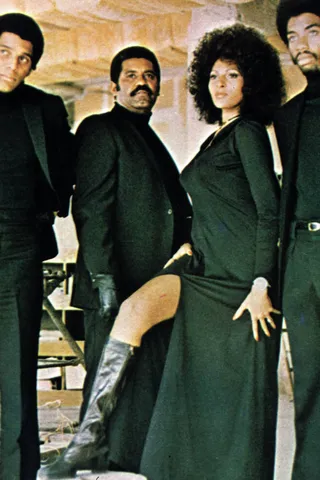

Foxy Brown, dir. Jack Hill, 1974

Corman, who discovered Grier when she was a switchboard operator at his American International Pictures, quickly observed that her talents far exceeded merely being tortured shirtlessly. In Women in Cages (1971), Grier is chic and sadistic as a prison guard in tailored fascist safari wear that accentuates her legendary curves. Her role is that of a deranged lesbian dominatrix prison guard with a lascivious sneer, who revels in the psychosexual downfall of her prisoners and eventually becomes their victim. Grier brought so much flavor and veritas to the role that she was again cast by Corman and cult film director Jack Hill in The Big Bird Cage (1972). In the film’s opening scene, Grier, as the lounge singer Blossom, is grooving in a skimpy white wrap top and matching hip-huggers, looking like a sexualized Osmond. When her guitarist plays a wrong chord, she stops singing, grabs his guitar, splinters it against a table and picks up the sawed-off machine gun that had been stashed inside. It’s a fine introduction that lets us know this chanteuse plans to bring more than tears to your eyes. Blossom is the fiery, revolutionary girlfriend of a guerilla gang leader (and her guitarist) named Django, and she’s always ready to throw down at a moment’s notice.

The next time we see Blossom, she threatens to castrate her philandering boyfriend with a machete while wearing flared jeans and a miniscule red cotton vest—tenuously held shut by a string—with coordinating neck scarf. After the brawl, she and her paramour make out in a giant mud puddle. Blossom soon infiltrates the women’s prison; shortly after, when another inmate calls her a racial slur, Grier—in a chopped-and-screwed cutoff prison work shirt—handily jujitsus her fellow prisoner into submission and hisses, in legendary and indomitable fashion, “And it’s Miss N—to you!” After that, Blossom runs the place. (She and Django ultimately free the incarcerated women, who were forced to process sugarcane in a hazardous machine called the big bird cage.)

By 1973, after filming Hit Man and Black Mama White Mama, Grier had arrived firmly in Leading Lady Land, during a delectably flamboyant, often lubricious, cultural moment of exaggerated fashion silhouettes and embellishments: fake-fur boleros, patchwork ponchos, A-line minis, wide collars, bulky ruffles, floppy sleeves, low-slung bell-bottoms, oversize hats and fat ties, with a surfeit of chunky jewelry and baroque polyester prints in explosive hues. Grier secured her status as the first Black female action star in Coffy (1973), in which her character, an ER nurse, seeks vigilante justice against a narcotics ring. “This is the end of your rotten life, you motherfuckin’ dope pusher!” she cries, before removing the drug dealer’s head with a sawed-off shotgun. (He had gotten her sister strung out, see.) Coffy goes on a rampage in outfits the colors of Monument Valley—sandstone, rust and peachy oranges that pick up the warm highlights in her perfect skin. While manipulating a pimp-like underworld honcho, Grier, in queenly fashion, dispenses orders in a white crocheted bikini from her poolside deck chair. However blaxploitative, the role is an awesome flexing of bitch-goddess female power. In Grier’s style, it should be said, the semiotics of power are never conservative—she always triumphs over adversity while fully sexualized and flaring, a vengeful Venus in clingy Qiana pantsuits who might kill you or make violent love to you.

After Coffy, Grier experimented with genres beyond blaxploitation and sexploitation, starring in the surprisingly good horror-schlock offering Scream Blacula Scream (1973), as an elegantly attired voodoo priestess: figure-hugging sheaths, pussy bows, a khaki jumpsuit, African jewelry made of feathers and beads. But the exploitation films were still paying the rent. Grier does kung fu disco during the opening credits of Foxy Brown (1974), considered among the most influential of all blaxploitation films and the one that made Pam Grier an archetype. Fashion-wise, the movie is prime Grier: She rocks a yellow crushed-velvet halter dress, a red backless jumpsuit and other indelible looks, accented with enormous hoop earrings, chokers and a variety of glamorous, chameleonic hairstyles—sleek pageboy, flowing locks, impressive Afro. Foxy’s 14 costumes were created by the designer Ruthie West, who also kitted out hitmakers like the Jackson 5 and Thelma Houston.

From left: Jackie Brown, dir. Quentin Tarantino, 1997; Friday Foster, dir. Arthur Marks, 1975; Women in Cages, dir. Gerardo de Leon, 1971

“She always triumphs over adversity while fully sexualized and flaring, a vengeful Venus in clingy Qiana pantsuits who might kill you or make violent love to you.”

Antonio Fargas, the actor best known as Huggy Bear on Starsky & Hutch, plays Foxy’s feckless, dope-dealing, numbers-running brother, who runs afoul of a sex-and-heroin-trafficking ring led by a cold redheaded woman with a predilection for gaudy gold pendants. Foxy infiltrates her circle with little difficulty but ends up being captured, beaten, drugged and raped.

“You’re gonna have to kill me,” Foxy says, panting and sweating in a white bra and torn shirt, still tied up after being worked over by the fists of madame’s thugs. “Or I’ll kill you. It’s gotta be one way or the other.” This is the kind of definitive Grier moment that really inspires: Even at her weakest and most defeated, bound and half-naked, she is still fiery and defiant. You cannot kill her fight.

After a daring escape from “the ranch” and her sadistic, racist jailers, Foxy decides to go full-blown revolutionary for the People. “I want justice,” she explains to a neighborhood action committee she tries to recruit, ultimately convincing the activists to support her cause in a fireworks-patterned blouse. “I want justice for all of ’em…and for all the other people whose lives are bought and sold so that a few big shots can climb up on their backs and laugh at the law and laugh at human decency.” As Foxy, Grier gives Black Panther–era Angela Davis a run for her money, and moviegoers the opportunity to consider revolutionary socialism (or something).

Following the popularity of Foxy Brown, Grier’s roles became decidedly more glamorous, and costumers began allowing her to look rich. The thumpy bass and muted trumpet music is wobbling into high gear in Sheba, Baby (1975). As Sheba, Grier is street-smart, coiffed to perfection in a Sears catalog’s worth of stylish sportswear, including denim outfits that would look as at home on the dance floor of Soul Train as they do kicking a bigot in the face. A soul singer belts over the opening credits: “She’s a dangerous lady / and she’s well put-together.” Damn right. This time Grier plays a private eye with a shoulder holster, who cleans up beautifully in a white suit with a wide-brimmed hat, string pearls and Louis Vuitton luggage. In the film’s climax, Sheba blows away her enemies with a submachine gun, while speeding across a lake on a bright yellow Jet Ski, wearing a royal-blue wet suit.

Friday Foster (1975) features one of her most iconic roles, with Grier playing a model turned photojournalist combating a crew of dirty cops (led by a young Carl Weathers). When a model is stabbed at a local fashion show—the designer is played by the effervescently naughty Eartha Kitt—Grier decides to get to the bottom of it by attending a gala in Washington, D.C., wielding her feminine wiles in a white, strapless, floor-length silver-sequin-trimmed column and matching coat. Throughout the film, Grier’s frontal assets are accentuated by low-cut batwing blouses, snug button-downs—and a plush white bath towel.

After 1977, Grier seems to have taken a little me-time; she doesn’t reappear on the big screen until 1981’s Fort Apache, the Bronx. Grier looks wildly sexy and is occasionally hilarious as Charlotte, a killer junkie prostitute, prowling the streets in a long, blond wig, winged eyeliner and a cleavage-spilling green-tiger-print dress with a razor blade stashed in her bra. Her long limbs are noodly, she’s so high she can barely stand up—but however vulnerable Charlotte is, when she fixes her big brown cat eyes on her victims, her entire psyche turns to ice as she pulls the trigger. It’s a tremendous bit of character work: While we sense that most Pam Grier characters are, to some extent, Pam Grier, this hot, fucked-up-mess of a character is a real departure, and Grier delivers it with a lot of humor and silky Black vernacular.

Left and center: Hit Man, dir. George Armitage, 1972; right: Coffy, dir. Jack Hill, 1973

Grier did 14 feature films between 1983 and 1996, including cult favorites like Above the Law (1988) with Steven Seagal, Bill & Ted’s Bogus Journey (1991) and Mars Attacks! (1996). The reification of Pam Grier included arguably her best role, in Quentin Tarantino’s Jackie Brown (1997), a lyrical paean to the archetype that made her famous. Tarantino knew enough to recognize Grier as his muse, giving her a vehicle where she could trot out her real acting chops and pour gravy on them. Jackie, a 44-year-old stewardess dressed in the padded shoulders of a previous decade, is a woman on the brink of going to prison for importing a gun dealer’s cash into the States. In the film, her fashion trajectory mirrors her emotional one, from down-on-her-luck uniformed flight attendant to confident conspirator in a black Kangol cap, hoop earrings, marcelled waves and a sleeveless black top.

What shouldn’t even need to be stated is that, despite the passing of the years, Ms. Grier is still exceptionally bangingsome—very sexy in the mind, like a mature French actress. She is emotionally sophisticated, her eyes conveying numerous emotions: fear, bravery and a cold-blooded willingness to shoot—notably, in a scene wherein she is waiting in a dark office for her adversary. She stares at the door, anticipating his arrival, and practices picking up the gun and pointing it at him, all with grace, beauty and quicksilver femininity.

Grier has worked continually in films and television since Jackie Brown, perhaps most visibly in 70 episodes of The L Word playing Kit Porter, the menopausal member of the ensemble. What is excellent about Grier in The L Word is that even in a very vulnerable place—namely, the abounding insecurities felt by an older woman—there is still an anchor in her psyche that I like to believe is the certain knowledge that she could kick that skinny white boy’s ass if he does her wrong. She lets her inner Gorgon fly when she castigates a patron for doing drugs in her nightclub. “You can fuck up your own life, but don’t fuck up my club!” she shrieks. It’s an anger you don’t often get to see in beautiful women, one that is usually played down, or coldly—but Grier’s temper is decidedly hot, despite her modest, age-appropriate outfits: tunics, boxy jackets, tasteful neutrals. The iconic sex symbol graduated into being cast as a real woman.

Literary critic Julia Kristeva spoke about “restorative perversion” being something transgressive that people indulge in when they’re feeling low. I’ve wondered for a long time what a restorative perversion could look like for women, since the idea of it being simply shopping was just too grim. Blaxploitation movies earned a bad name somewhere down the line, but the Pam Grier character has always been a fusion of sex and raw power—a beautiful woman with the agency and competence to overcome dreadful circumstances and, by fighting the good fight, emerge righteous and victorious. Watching Pam Grier films, I realized that they are genuinely cathartic if you’ve had a few bad experiences with men: Sometimes the machete or the machine gun just feels like the right way to go. Transgressive, yes, but is pleasure not innately transgressive? Pam Grier is nothing if not the embodiment of that rawest of female pleasures, the revenge fantasy. In that sense, she is restoratively perverse—but in a way perhaps only the women really understand: in high heels, with an hourglass figure, beating up men not as a brute but always as a sex symbol.