Queen of Business

By Mike Albo

Ruth Gordon and Bud Cort in Harold and Maude, dir. Hal Ashby, 1971

Queen of Business

How Ruth Gordon changed the face of dark comedy and Hollywood’s notion of an aging actor

By Mike Albo

August 16, 2023

Early on in My Side, the longest of her three memoirs, Ruth Gordon is upset. It’s 1920 and she is the lead in the Chicago production of Booth Tarkington’s hit play Clarence. It opens with great success, and despite the glowing reviews (“She will be a star in five years,” says the Chicago Journal), the producer George C. Tyler has returned to see the show. (“For confidence I had a martini,” writes Gordon.) Tyler isn’t happy with her performance. She is ruining the show, he says, and he gives her notice.

Gordon’s first husband, actor Gregory Kelly, co-starring in the production, begs Tyler off and says he’ll work with her on the role in their hotel room. “Hold it all together, don’t let pauses in,” Kelly coaches the 24-year-old ingenue. “A pause is hard to act around…try cutting out all the pauses.”

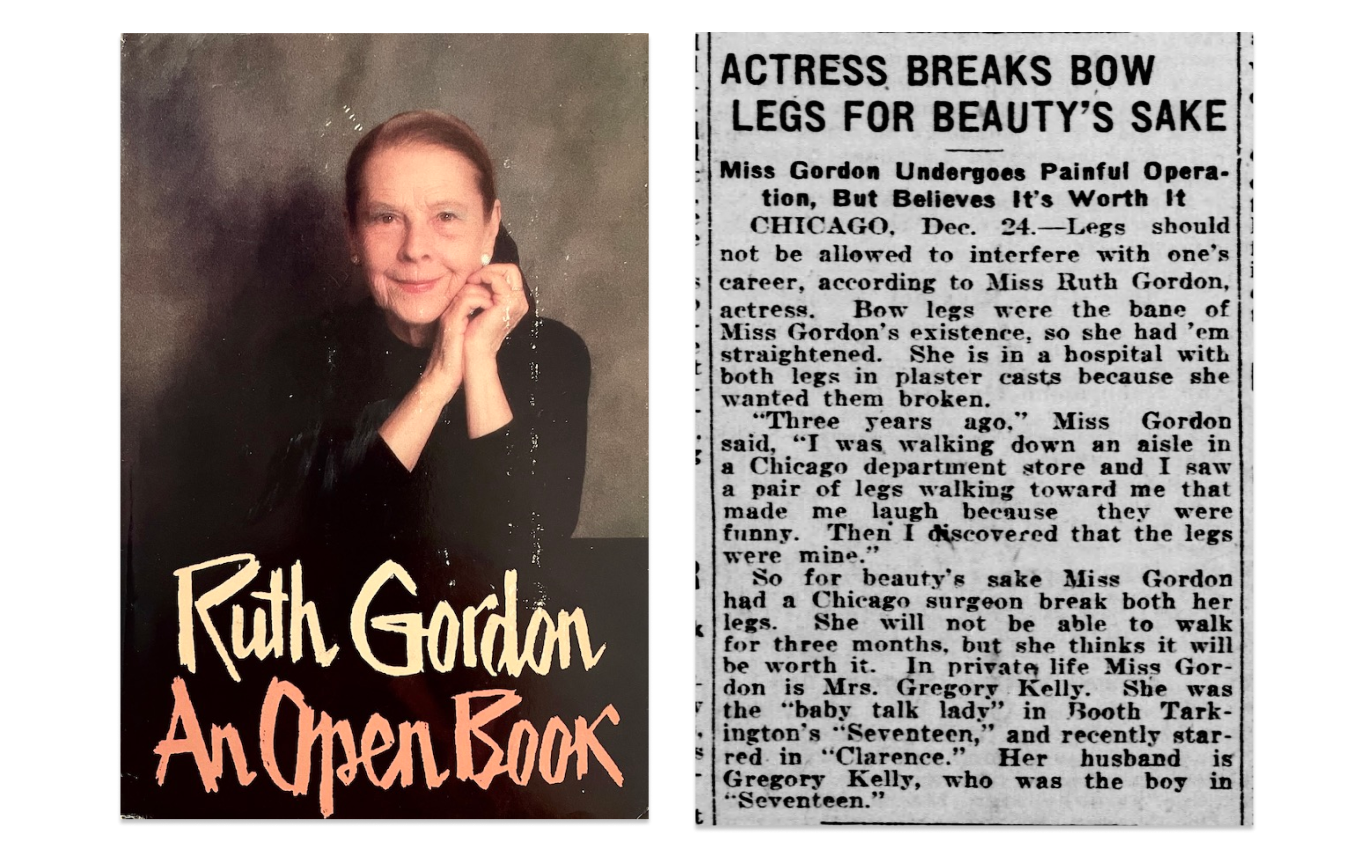

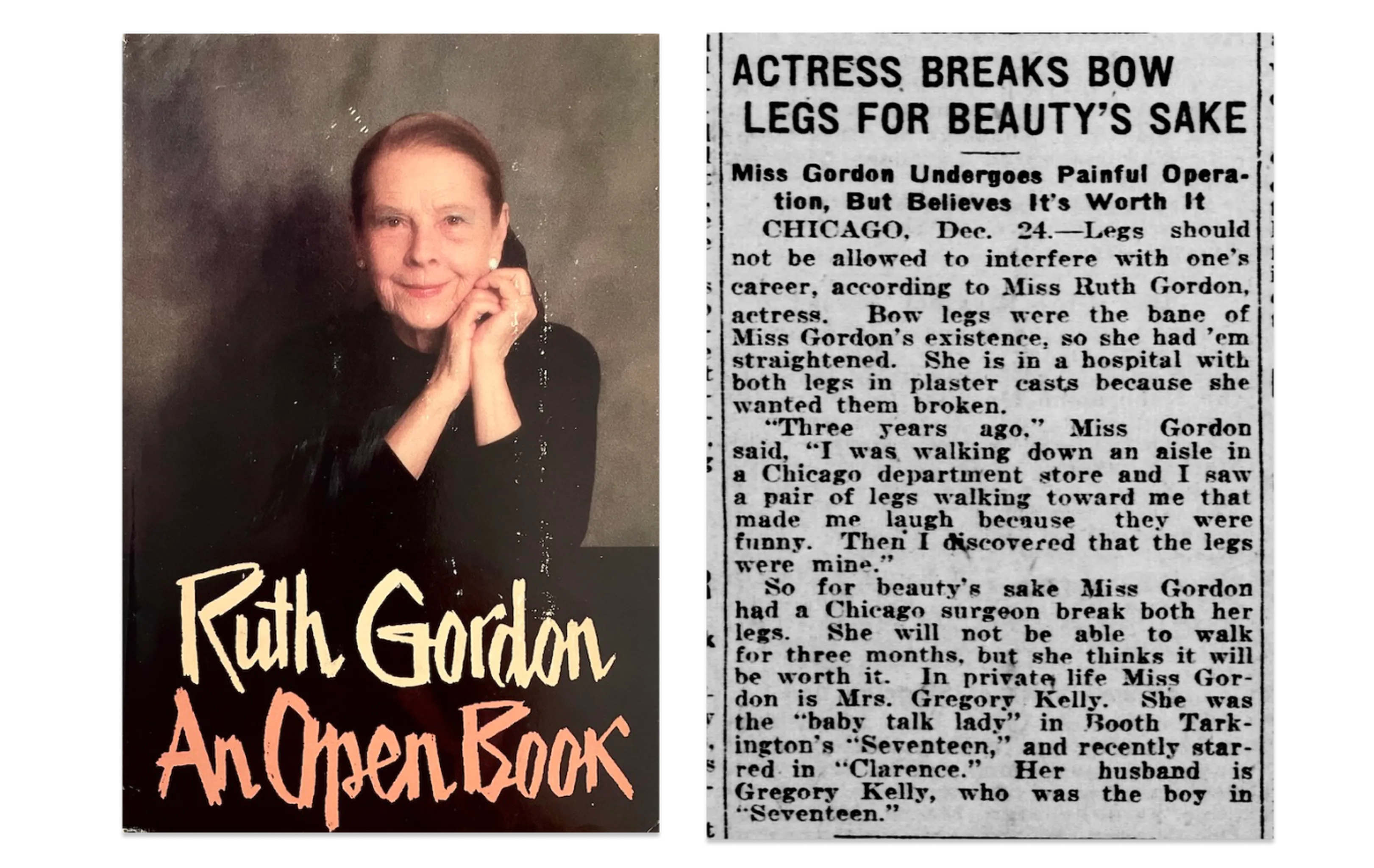

Left: Ruth Gordon’s memoir An Open Book

Right: Ruth Gordon makes headlines

Ruth Gordon never paused again.

In her books, screenplays and, above all, her craft on stage and screen, Gordon “performs,” talking a lot while also talking with her hands. In place of dramatic silences and glowering Hollywood stares, she fills space with words, tics, sighs, asides and plenty of chunky jewelry. Her turns in Roman Polanski’s Rosemary’s Baby (1968) and Hal Ashby’s Harold and Maude (1971)—the apogee of Gordon’s career, when she was already in her 70s, an age when most Hollywood careers are in sharp decline—not only canonized her as the vivacious, zany, offbeat older woman she so often played. Those films also introduced audiences to an entirely new strain of mannered comedic acting. Long before the word tragicomic was even coined, Gordon was delivering her devastating lines casually, serving humor with horror. “He chose you out of all the world. Out of all the women in the world he chose you!” she famously says in her Oscar-winning role as Minnie Castavet, Rosemary’s nosy neighbor in the Polanski classic. Gordon tosses out the lines with a tired gesture like so many old throw pillows. (Note that the “he” she’s referring to is none other than Satan.)

The stagecraft known as “business” is Gordon’s playground. When Rosemary (Mia Farrow) first allows Minnie inside her apartment, Gordon gasps and gushes over the décor—“Oh oh my, nice paint job!”—while her overladen charm bracelet, like the third actor in the scene, clinks and clatters. Gordon’s acting style is all about this kind of buried intention; skirting around the subject, dithering and casually obfuscating—which is how most humans actually behave. Rarely do any of us say anything dramatic, much less stand still and pose while waiting for a close-up (except maybe influencers).

Throughout the bleak, death-obsessed black comedy Harold and Maude, about a May-December romance between two social misfits, Gordon gleefully serves pie or advice without reserve, like a spinning lazy Susan. When Harold first sees Maude at a funeral, she is sitting on a tombstone cramming fruit into her mouth, then a bit later, at church, she sits behind him, offers him licorice and barely stops talking until she speeds recklessly away in a stolen VW bug. “I’ll never understand this mania for black. Nobody sends black flowers, do they? Black flowers are dead flowers,” she says as they leave the funeral. Somehow her verbosity is the opposite of irritating; it’s entrancing. She rambles about how she’ll turn 80 in a week, and that seems like a good time to die, but does so in a breezy way, like death is as common as a bowel movement. Despite it all Gordon’s Maude is full of life, the energy-giver to Bud Cort’s morose, pale, disturbed, early-20s Harold.

Gordon knew how to channel her enormous reserves of fuel. She was known for it. A tribute to her career in 1968 at the Academy of Dramatic Arts in New York credits her “vast energy and a volatile mind.” When she died at 88, in 1985, Garson Kanin, Gordon’s husband of 43 years, remarked that her last day was “typically full, with walks, talks, errands and a morning of work on a new play.” She had made a public appearance only two weeks before, at a benefit showing of Harold and Maude, and had recently finished acting in four films. “In one of them, characteristically enough, Miss Gordon insisted on doing her own motorcycle stunts,” her New York Times obituary informs us.

Ruth Gordon and Mia Farrow in Rosemary’s Baby, dir. Roman Polanski, 1968

Gordon’s life and career spans seven decades of theater and film, from Silent Hollywood to Old Hollywood all the way to New Hollywood. She was born in 1896 in Wollaston, a neighborhood in Quincy, Massachusetts, where, she describes in My Side, “the Elizabethan language kept going as late as the 1900s.” Seeing actress Hazel Dawn at 15 in The Pink Lady, a musical comedy that would have scandalized her parents (the women wore frilly dresses and were touched on the hips by men), electrified her. “Go on the stage, Ruth, go on the stage! Be an actress!” Gordon’s inner voice told her.

If there is one unmoving aspect of Gordon, it is this—an ironclad backbone of ambition. At her high-school graduation, she went on stage to receive her diploma and, shaking the hand of the headmaster, said to herself, “You’re Superintendent of all the Quincy schools…but you are never going to be a visceral myth, I am the only visceral myth in this auditorium.” Celebrity memoirs are often like this—those who are successful enough to write them lack crippling self-doubt, and if they do, they repurpose their weaknesses as obstacles on their predetermined pathway to fame. Insecurity is just a plot point. “Humidity, humility, two words that don’t appeal,” Gordon exclaims in her third memoir, An Open Book. It’s written on a page by itself.

She left Wollaston to become an actress at age 17. Her father, a factory foreman, bought her a one-way ticket, gave her the money for one year’s tuition to the American Academy of Dramatic Arts, pinned $50 to her corset, and handed her his old spyglass to hock. (She never did sell it.) Her first break happened not long after, when she played a Lost Boy in a 1915 Broadway production of Peter Pan. Drama critic Alexander Woollcott raved, “Ruth Gordon was ever so gay as Nibs!” Woollcott introduced her to the Algonquin scene, and she fell into the close-knit circle of New York’s artistic elite. “In 1914, everybody didn’t hightail it into the movies,” Gordon writes. “All the beautiful people went on the stage in New York City.”

“humidity, humility.

two words that

don’t appeal.”

Despite befriending luminaries like Thornton Wilder and Vivien Leigh, Gordon describes herself as just an average girl from Quincy with a dream. “What did I have to offer? No looks, no singing voice…What market was there for that?” Perhaps in Hollywood terms she wasn’t as ravishing as Leigh, but Gordon’s face is an argument that beauty comes from within. In her 1979 Emmy-winning role in the sitcom Taxi as a rich woman trying to hire her driver (Judd Hirsch) as an escort, you see an elegant, seasoned woman at age 83—hair pulled back, in a fur jacket with big pearl earrings—her years a part of her magnetism.

Left: Spencer Tracy and Jean Simmons in The Actress, dir. George Cukor, 1953

Right: Ruth Gordon in Harold and Maude, dir. Hal Ashby, 1971

Her first starring role, in a 1918 staging of Tarkington’s Seventeen, was not well received. The New York Tribune said: “Anyone who looks like that and acts like that must get off the stage.” Still, Ruth Gordon persists, acting in dozens of productions, including Nora in A Doll’s House (Martha Graham taught her the tarantella), Wilder’s The Matchmaker and countless more.

Along the way to fame, Gordon seems to have met everyone: FDR, Helen Keller, Dizzy Gillespie. Lillian Gish gave her an opal necklace. Harpo Marx accompanies her to visit Somerset Maugham, who takes an instant dislike of her after she criticizes his new play. In 1970 she describes going to then-hotspot the Ritz-Carlton and once again offers a half page of boldfaced names: “Natalie Wood or Mia Farrow or Ali MacGraw or Barbara Harris or Betty Bacall or Mike Nichols….” Remembering her close friend Vivien Leigh: “Little Vivien! She knew what to do about everything except find a reason to live.”

Beyond her three memoirs, Gordon proved an exceptionally prolific writer. That output includes her famous autobiographical play, Years Ago, which became the 1953 film The Actress starring Spencer Tracy, Jean Simmons and a young Anthony Perkins in his film debut. In My Side, she says that MGM paid her $100,000 for the George Cukor–directed dramedy, but neglects to mention she also wrote the screenplay. “It plays a lot on TV,” she writes with a shrug.

Whether it’s modesty or deliberate obfuscation, Gordon rarely talks about her writing career. But along with the Academy Award–nominated The Actress, she wrote 13 films and teleplays, often with Kanin, including Adam’s Rib in 1949, which starred Tracy as well as Katharine Hepburn. Her oeuvre is impressive by any standard—especially so for being a woman at the time in the industry. But in all her accounts, she never addresses sexism or harassment except for a few tiny asides. Maybe by the time she was working as a writer, married to Kanin and ensconced in the scene (Tracy and Hepburn were both friends), she was protected from untoward behavior, but these days none of us are naive about Hollywood and what it took, and takes, to be a woman in it.

Left: Jennifer Coolidge in The White Lotus

Right: Ruth Gordon in Harold and Maude

In place of stark tales in her memoirs, there are pages of snappy dialogue—a nod to her screenwriting talent—that read like scripts without the margins and Courier font, as well as fabulous stories befitting a star. In 1920, when she gets her knees broken to fix her bowlegs (“it’s hard enough to be an actress without handicaps”), the news makes the front page of the Chicago Examiner (“BREAKS LEGS FOR BEAUTY’S SAKE”) and her hospital room is instantly filled with flowers and cards. While recovering, she wears what any First Lady of American Theater would wear: “a bed jacket of peach taffeta, the neck and sleeves outlined with white marabou.” Her memoirs are like this, as if Diana Vreeland were sitting next to Gordon, holding her martini while she jots down her thoughts.

On the internet, there’s no end to the backstage lore about Rosemary’s Baby—that Frank Sinatra divorced Farrow during filming, that Cassavetes and Polanski were at odds, that the director forced Farrow to run into traffic, that the title is an anagram for “a brassy embryo.” In the many comments you can find on Reddit about the film, one writer mentions how throughout the film, Gordon never looks at Farrow directly. Whether this can be definitively proven is debatable, but it tracks—Gordon plays Minnie like she is always avoiding the truth, her eyes wandering, making idle chatter while also making sure Rosemary drinks her satanic smoothies. It’s both deeply human and a definitive performance of the banality of evil.

Gordon appeared in dozens of Broadway plays, feature films and television shows. Her eccentric, naturalistic style can be seen today in the multitude of dark comedy streamers, from Dead Like Me to Baskets or Beef. If there is one direct descendant of Gordon’s style it’s Jennifer Coolidge, another brilliant comedic-dramatic actress who, as Tanya McQuoid in The White Lotus, speaks in barely meaningful sentences, as if her thoughts are plastic bags floating in the wind, but inside her you can’t help but sense a cauldron of pain and resolve.

.png)

Ruth Gordon on set of The Three Sisters, 1942

“I wanted to be an actress in 1912, I want to be an actress today,” Gordon writes at the end of An Open Book. She describes what happens every time she walks on stage and makes that “first terrifying sound” from her throat. “[T]hey describe [it] as a voice,” she writes, “but that first instant it is a siren of terror and intention and faith and hope and trust and vanity and security and insecurity and blood-curdling courage which is acting.” It’s a beautifully written sentence. But say it in your best Ruth Gordon voice and it sounds even better.