Ryuichi Sakamoto: Encore

By Robert Bound

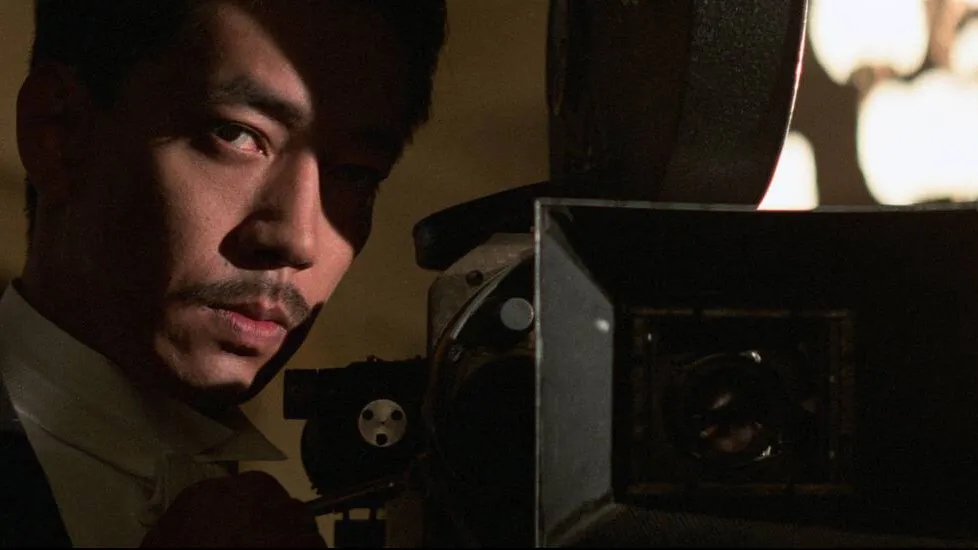

Ryuichi Sakamoto: Opus, dir. Neo Sora, 2023 (film stills courtesy KAB Inc.)

Ryuichi Sakamoto: Encore

In the intimate concert film Ryuichi Sakamoto: Opus, directed by his son, the late composer gives a performance for the ages

By Robert Bound

March 28, 2024

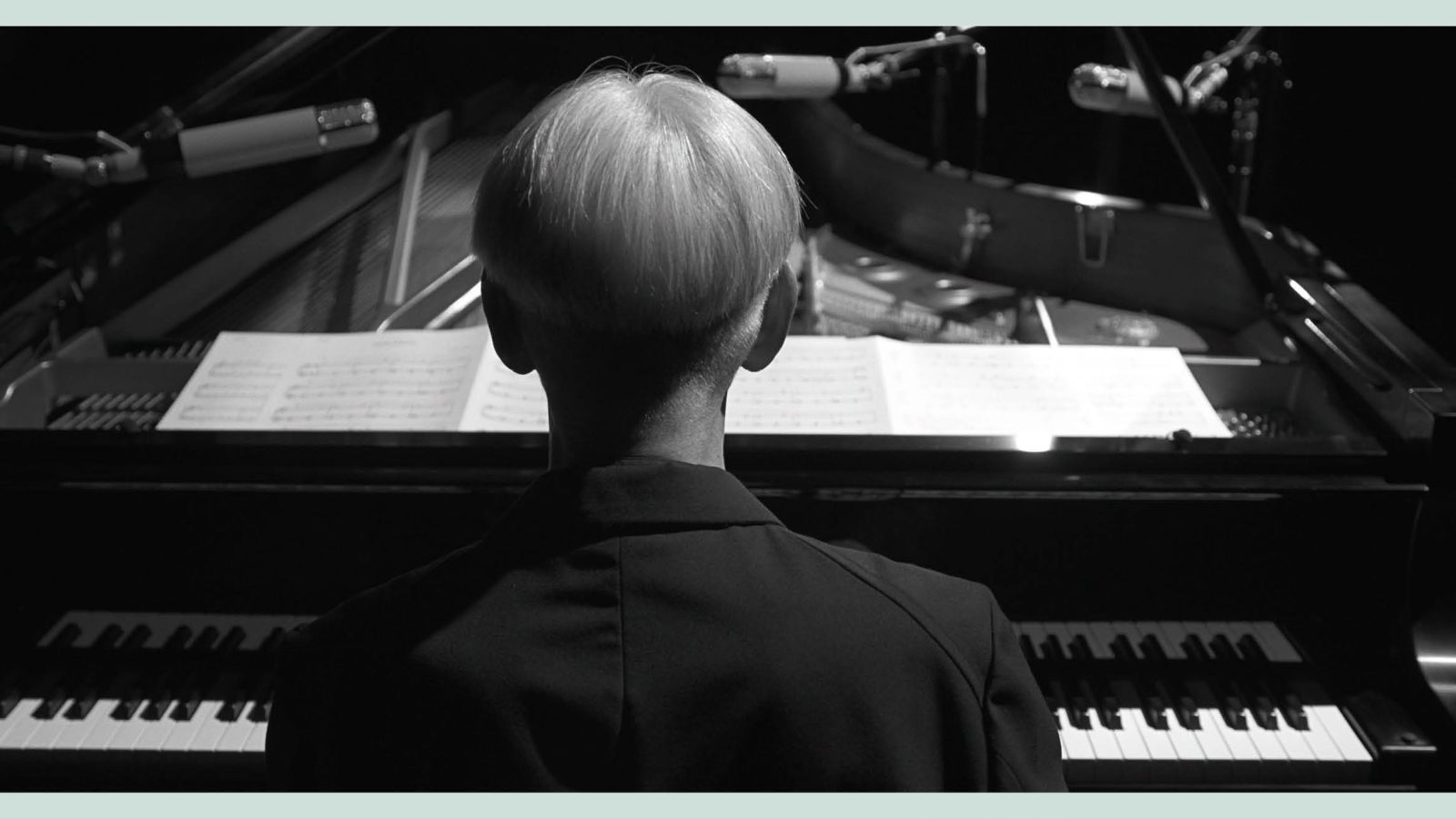

Ryuichi Sakamoto: Opus is a concert film like no other. It documents the final concert given by the towering Japanese composer Ryuichi Sakamoto (Merry Christmas Mr. Lawrence, The Last Emperor, The Revenant) and pop star (as a solo artist and with Yellow Magic Orchestra), who, sitting at a polished black grand piano in a cool white studio, delivers a performance of grace, poise and control against the backdrop of the bruising battle with cancer that would take his life in March 2023. Shot without an audience in black and white over eight days in Tokyo in fall 2022, Opus is an intimate and elegant work that places Sakamoto’s music and performance center stage. Directed by his son, Neo Sora, and produced by his wife and manager, Norika Sora, the film is also a family affair. Galerie spoke to Neo Sora about the experience of directing his late, legendary father.

Ryuichi Sakamoto at work

Opus is a beautiful film and feels like a fitting swan song to your father Ryuichi Sakamoto’s career. How did you approach something that has the feel of a final testament?

Well, while we were making the film, we didn’t necessarily know that it would be a swan song. It’s impossible to know these things, as he had come back from cancer in the past. And so we hoped again. Having said that, we definitely approached the film with a seriousness and precision, imagining that it could be the last word. While I was able to use my own relationship to my own father—having that privilege that other directors would not necessarily have—I was also trying to approach the filmmaking in as professional a way as possible. I wanted what became Opus to really be a conduit for my father’s ideas, to really honor him, to show him in a dignified manner as he was playing the concert. Those were really my concerns.

The aesthetic is very pared back, and you harness the elegance and precision of shooting in black and white. Is there also a sense of that monochrome being a historical format as well something suggestive of posterity?

My broad approach is to have every creative decision flow from the core of the film, the thing we’re trying to capture. For me, that core was the performer’s physicality. Another impetus for making the film was the fact that my father couldn’t do any more world tours, because of his health and illness. He wanted to leave this piece behind before he passed away, before he didn’t have a physical body to do it anymore. All the music that he plays and some of the new arrangements of older tracks are much slower, and that comes from his inability to use his hands in as dexterous a manner as before. So that physicality and the concept of time are linked. I think his interest in the concept of time came from the fact that he had to confront his own mortality. Because he used to be quite a tough guy, you know—he would be able to be in the studio all night long and then go out on the town drinking and then come back for work for another day and then write an orchestral composition for Bernardo Bertolucci! He was able to do these things. But then there was a certain moment during his first cancer, I think, where he really realized that his body couldn’t handle that anymore. So there is a concern about this physicality. The choice of shooting in black and white came from that: We were trying to concentrate on the texture of his body and how his body was kind of fusing with the piano, the body of the piano, in order to create his music.

Ryuichi Sakamoto: Opus

Well, your father’s black suit and black piano against the white studio walls look incredible.

They do, and there’s the little added bonus that he had pretty striking silver hair. So that looks really good, which helps. Maybe if it weren’t for the silver hair, we wouldn’t have made it black and white and the whole concept could have been different. But seriously, yes, those were the ideas that flowed into the style of the film.

The angles you chose to shoot from are particularly beguiling. Sometimes we feel like we’re over Sakamoto’s shoulder, watching him play. Then we’re right down at the level of his hands on the keyboard. Another shot might be side-on to reveal Sakamoto’s profile against the interior of the studio. How did you choose your shots?

It very much depended on which track we were shooting at the time, and we really thought through the camera angles and the shot list for each. We sent all the camera operators the recordings of the music beforehand so that they could really understand it and react physically to listening to my father play. As for the different kinds of shots you’ve described, I had a different consideration for each. So, first shot, where we’re behind my father from the back and the camera gradually dollies in and then goes over his shoulder—to be honest, that for me was my perspective of how I would see him play. Every time I would sneak up on him or go downstairs to his home studio to call him for dinner or something, he’d be playing his piano with his back to me. So that’s the perspective with which I wanted to start the film. Kind of my perspective.

That shot is not something that the average concertgoer is party to. It’s very intimate.

Well, that intimacy is something we were really thinking about. Back in the day, when my parents would take me to a classical concert or a piano recital or something like that, we might be in a really grand hall, and physically you’re at quite a big distance from the performer. But a lot of people have had this experience of being drawn into a performance when the music starts playing. Suddenly that distance disappears and it feels like you’re really close to the performer. And that experience of what it’s like to be at a concert is something we really thought about. We were trying to use some of the camera movements to mimic that and imagine the point in the track when you would get drawn in. At a certain point, maybe my father’s playing something really epic and grand—so actually what we want to see is like a landscape, you know, and so we were trying to mimic grand landscapes, in terms of the lighting and the scale of the shot. There’s a track we shot called “Solitude,” from my father’s soundtrack to the film Tony Takitani (2004), which is told almost entirely in tracking shots, and so we tried to mimic a little bit of this sideways thing for that one. Those were some of the considerations that went behind deciding on the shots.

From left: The Sheltering Sky, dir. Bernardo Bertolucci, 1990; The Last Emperor, dir. Bernardo Bertolucci, 1987; The Revenant, dir. Alejandro G. Iñárritu, 2015; Ryuichi Sakamoto in The Last Emperor

And what about the set list—was that as rigorously thought through, and when was that decided upon?

We shot Opus in September 2022, and my father had come up with a set list that July. It was a fairly rough list of the tracks he was curious to include. And then over the course of maybe a couple of weeks, he would start to pare it down and reorganize things. At a certain point, I told him my concept of wanting to show the passage of time in a day—from night to morning and back again. Taking that in, he rearranged some of the music in order to fit this idea. But these decisions were unusually far in advance for him: He usually came up with the set list a day in advance of the concert, and he would even change it on the day, depending on the atmosphere of the audience or whatever. This was a little unusual for him. That he decided on a set list so early was something of an imposition that I, as director, had to impose on him.

Cracking the whip, right? And how long did the shoot last?

There were nine days in total: a day for setting up and then eight days of performing and capturing the performance.

There are some intimate moments in the film in which your father cracks a smile after playing a certain track or sighs a little and asks for a break. These seem to go beyond even the knowledge that this is a family affair—they become moments of frailty wrapped up in the essence of performance. How did you decide on how many of these moments to include in the final film?

We did shoot a little bit of behind-the-scenes stuff, even away from the piano. But in the end I wanted to stay true to the idea of showing my father in a dignified way. During concerts he would sometimes emcee a little bit to the audience, but for Opus, because we didn’t have an audience there for him to respond to, he would just play. On the one hand, I wanted to be a purist in terms of capturing the concert and giving people a cinematic translation of what a concert might be. But on the other hand, I am a filmmaker and there is drama in the story. And the drama is that he’s finding it extremely difficult to play the music that he used to be able to play effortlessly. I wanted to give people that slight hint, and I wanted to build that into the film. I’ve kept certain moments where he was really tired. Every time before playing something, he would be exhausted and kind of listless, and I tried not to shoot too much of that, because I didn’t want that to be the focus of the film. But not to have had it at all would have been a lie, too. One more thing I want to say is that his playing of the music was exhausting in the way that having a good cry or a really good laugh is—that you go through intense emotions and then you’re exhausted. But you also feel good.

From left: Neo Sora and his father, Ryuichi Sakamoto

“Music is really the attitude of the listener rather than the sounds themselves.”

We should really point out that there’s so much delicacy, control and poise in your father’s performance in the film. I also wanted to ask about the sound mix in Opus, in which you have included the sound of the piano’s pedals—particularly the soft pedal, which almost takes on the atmosphere of a muffled drum. Is that again about intimacy?

That really comes out of what we were talking about before, which is physicality. The physicality of the piano, which is something that my father himself was very interested in, probably ever since he heard John Cage and absorbed an important idea: that any sound can be music. Music is really the attitude of the listener rather than the sounds themselves. I think that’s something my father was really influenced by early on and kind of held on to until the very end. And Glenn Gould, who was actually a really big inspiration for my father. I don’t know if you’ve listened to a lot of Glenn Gould recordings, but you can hear him humming along and sense his body rocking back and forth as he plays. So it was very much about capturing the philosophy and the physicality of that. I also really liked the sound of the pedal because it really sounds like a heartbeat. It has that deep resonance.

There’s something so in-the-moment that you’ve captured in Opus. People will be familiar with a lot of the music in the film and yet they might get the uncanny sense that they’re watching Ryuichi Sakamoto composing as he plays. Is there any sense in that reading?

Yes, and that’s a quality that’s shared across good performance in general—beyond music, right? Acting might be like that in a way, where you have lines that you’ve memorized and you’ve learned the blocking and the movement of what you’re supposed to do, but it still seems genuine. Robert Bresson and Yasujirō Ozu were very precise in how they directed actors, but when those actors performed, even on the hundredth take and even if it’s a line that’s been memorized so pristinely, it still feels like they just did it, that it just happened, that it’s genuine. And that’s totally true for music, where you learn lyrics or learn the music by heart until it becomes muscle memory. And then you forget all that: You play, and you’re still playing the things that you memorized, but you’re playing as if it’s the first time. That’s what creates the emotion. It’s really a magical thing to witness. A positive loop of simultaneously creating the feeling and feeling the feeling, and that pushes you to want to play the next note with more feeling. And in a film, that’s what the best takes are. I think my father was really aware of whether he did that in a take or not.

Opus ends with the piano on its own, and it’s a tender moment. Were the final scenes planned, or was it something that worked out in the making of the film?

Well, the sound engineers had another Yamaha piano, one that has this Disklavier technology that records the pressure and the speed with which you play the keys. And that’s just built into my father’s piano. When we went into the studio they had to tune up the device and were playing random stuff, but I was just staring at it. I mean, it’s mesmerizing to watch a piano play itself. When I saw this on the set, I thought that this could be the ending and how, well, ghostly that felt.

Caption