Same Person, Different Sex

By Cyrus Dunham

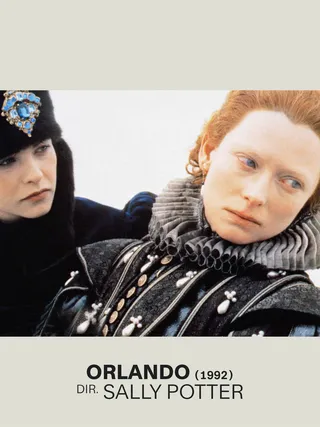

Orlando, dir. Sally Potter, 1992

Same Person, Different Sex

How Sally Potter’s revolutionary take on Orlando artfully anticipates the current conversation on gender and identity

By Cyrus Dunham

May 7, 2024

Sally Potter’s Orlando ends with an angel floating low in the sky. Singing in falsetto, the angel’s voice closes the film’s otherwise wordless, otherworldly score: “Yes, at last, at last, to be free of the past and of the future that beckons me / I am coming, I am coming, here I am, neither a woman or a man.” Orlando, leaning against a tree and staring up at the angel (played by Bronski Beat’s Jimmy Somerville) seems, after 400 years, something very near to content.

From left: Charlotte Valendrey and Tilda Swinton during Orlando's Stuart period

Orlando, based on Virginia Woolf’s iconic, centuries-spanning 1928 novel, is a near-perfect transmission of the book’s essence, if not the exact mechanisms of its plot. When Orlando (played by Tilda Swinton) first appears on camera in the year 1600, a voice-over tells us, “There can be no doubt about his sex…and there can be no doubt about his upbringing….” The literary Orlando’s immortality goes largely unexplained; in Potter’s film, words themselves render him eternal. Elizabeth I bestows immortality on the young aristocrat before her death, offering him and his heirs a palatial estate on one condition: “Do not fade. Do not wither. Do not grow old.”

Potter’s Orlando takes an expressionistic approach to the lyricism of Woolf’s history. She transmutes the narrative’s historical figures and events into arch performance, saturated color and diaphanous, synth-infused sound. Queen Elizabeth, for example, is played by Quentin Crisp like a postpunk drag mother (a “queen” of another kind).

In the film, the Great Frost of 1610, when the River Thames froze over and birds fell dead from the sky, is evoked by a dead woman, holding a basket of red apples underneath the cloudy ice. A wealthy, mustached man looks down at her, erupts in laughter like God created the scene for his entertainment, and proceeds across the solid river on a rolled-out velvet runner.

Orlando has his first brush with love on this ice. A winter carnival to celebrate the Muscovite ambassador’s visit. A gathering of tents. Music, dancing and feasts; Englishmen and Muscovites skating back and forth. Across the encampment, Orlando spots Sasha, the ambassador’s daughter. “Rather delightful, if that’s to your taste,” a fellow gentleman tells him.

Sasha and Orlando’s first kiss takes place on a smooth, frozen canal facing his estate. They sit on a luxurious sled, drawn by tired men on skates, puffing mist in the cold air. Orlando presses his lips against Sasha’s. A brief shot of a hunched-over, cloaked peasant carrying a huge bundle of sticks cues things that Orlando has never, and will never, know: a deteriorating body and the backbreaking effort of survival. We return to his face filling up the screen, pale, birdlike and red-haired, radiant with pain.

“Why are you sad?” Sasha asks.

“Because I can’t bear this happiness to end,” he says.

“But we are together.”

“Yes, now,” says Orlando. “But what about tomorrow, and the day after?”

Billy Zane and Tilda Swinton in Orlando

“In a world of false dualisms, tasting both is its own freedom.”

Sasha accuses Orlando of suffering from a strange melancholy, which is that he suffers sorrow in advance. She finds his fixation peculiar, even naive. Why cry for a loss that has yet to come? Neither she nor Orlando seems to know that he will live through countless losses as time passes, history flows and he never dies.

Orlando begs Sasha to stay in England, but she says it is impossible. When the ice melts, she must return to Muscovy by ship with her father. “You’re mine,” Orlando implores. She asks why. “Because I adore you.” His desire is a possessive tautology. His attachment is not enough to stop time or to keep Sasha from falling into the arms of another man. He waits for her at London Bridge, hears the crack of the ice, and knows she is gone. The river splits under his feet as another lowly peasant calls for help. One who lives forever still watches others die. He sees the rose fall from its stalk, shrivel and turn brown. Spring comes, winter ends and the ice thaws.

We watch Orlando stumble daftly through another hundred years, a hapless child of privilege. Throughout, he remains a man. Idling in an empty manor house with too many dogs and too many spare rooms. Still wounded by Sasha’s departure, he writes trite, rhyming poems about love and loss, the wickedness of women. In pursuit of something else, he takes up a station abroad. An ill-equipped ambassador in an unnamed Middle Eastern country. (In Woolf’s novel the city is Constantinople; the empty, echoing streets of the film connote a more dreamlike, barren place). After ten years the monarchy promotes him to the highest rank in the peerage. No locals attend his celebration party. He marches back and forth in a curly white wig, waiting for their arrival. As it turns out, the city is under siege. Orlando attempts to muster the kind of courage and fortitude he has notably lacked: He grabs a pistol and goes to battle. When an enemy fighter is gravely injured, Orlando returns to the fort. He sleeps for several days. Later he wakes up, revealing much longer red hair than we’ve seen. He washes himself with water, turns to the mirror, and takes in a new form: breasts, hips, the outline of a vulva.

With a slight smile on his usually perturbed face, he says: “Same person. No difference at all. Just a different sex.” The year is 1710. Orlando is now a woman, 110 years after the Queen’s strange bequest.

From left: Prince performing in Copenhagen, 1986; David Bowie as Ziggy Stardust backstage in London, 1973

Orlando’s sex changes unremarkably, the same way his clothes change from Rococo to Victorian, the same way his estate’s Elizabethan landscapes are replaced by geometric topiary. The passage of time; nothing more, nothing less. Time is ephemeral yet immovable. Time cannot be touched, held or tasted, and yet it is everywhere, happening always, not just to us but through us. As Orlando glimpses his own feminine form for the first time, rays of light illuminate thousands of particles of dust in the air. Flickering, they come into focus and then disappear.

Thirty-two years ago, the film audience that received Orlando had little knowledge of the concepts that presently define our understanding of sex and gender. Academics had begun theorizing the dichotomy between the two—sex as a fixed, material state, and gender as a malleable, social one—but this presumed split was only familiar to a small and marginal community. (For what it’s worth, scientists across disciplines now understand that sex’s formation is as mysterious and elusive as gender’s, a tangling of processes both biological and relational.) The panoply of words that shape our notions of sex and gender today—transgender, nonbinary and intersex, as well as 20th-century terms like transsexual, transvestite and cross-dresser—were notably absent from reviews and responses to the film. The libidinal economy of the late ’80s and early ’90s certainly shaped Potter’s treatment of the titular character. Androgyny, the provenance of icons like David Bowie and Prince, was the most available description for Swinton’s gender-fluid, sex-transgressing performance. Nonetheless, many critics balked at the improbability of a sex change, even a mysterious and magical one.

Orlando came out in 1992, the year I was born. A few months prior to the film’s release, my mother gave birth to me at Manhattan’s now-defunct New York Downtown Hospital. The doctors had declared me female by using sonographic imagery. In the grainy, blurred gray image, they detected the shape of an early vulva. There could be no doubt about my sex. The presence of external parts indicated something fixed and solid, told a story about what was to come. Now I am six feet tall, a man. From the outside, clothes on, there can be no doubt either. But I have run into acquaintances and watched them blink, trying to understand how something so familiar can be its own opposite. Same person. No difference at all. Just a different sex.

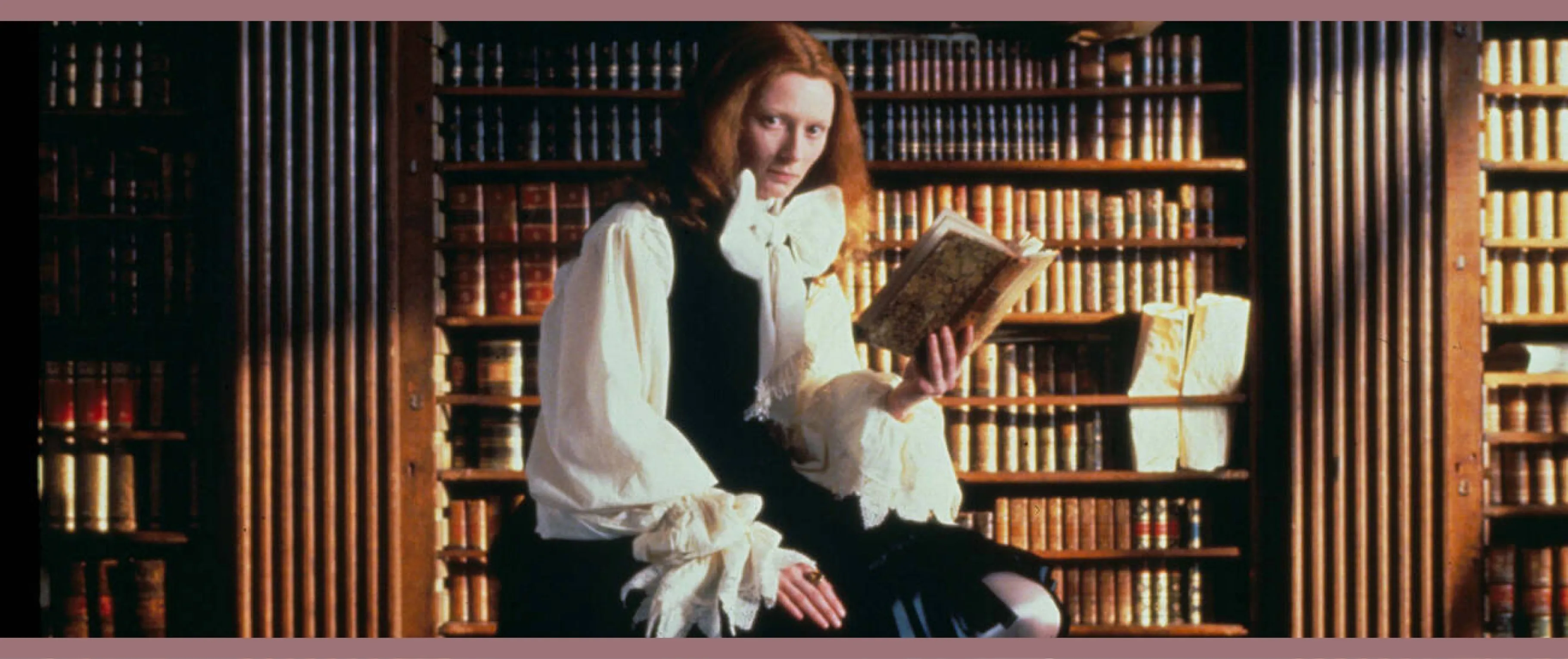

Orlando in full Restoration-era regalia

I am unsure, given the continual biological remaking of the human body through cell death and regeneration, whether my body’s difference from itself 7 years ago, 14 years ago, 21 years ago is any starker from sex-change than from a natural progression of aging in time (the latter being a condition Orlando was free from experiencing). The continuity of a name or a sex does not ensure sameness. Time does its work, remakes all matter eventually. Sex is one axis of possible transformation; there are infinite others. Yet the ongoing-ness of memory lays the ground for a continuous stream of being, the sense that I am the same person I once was, that things happened to me which will never happen again. There lies that strange melancholy of suffering in advance. Everything I know will eventually fade away.

A couple of years ago, late at night, I sat across a table from a slightly older woman. We were in an ornate, somewhat unkempt home—pink stucco walls, a 30-foot plate-glass window, a grand, dark wood staircase. An early Hollywood celebrity had built the house at the start of the 20th century. He died and the house remained, now inhabited by a revolving collection of queer people who traded rooms and, sometimes, genders. The woman I sat with was a mother, and a writer. She was visiting Los Angeles from England. I invited her to our party. We spoke about our sexes.

“You did something,” she said, “that humans have written about and dreamed of since the beginning. You traveled from one shore to the other and stood on both sides. It’s something most of us will never do. You’re very lucky.”

In Potter’s film Orlando falls in love one more time, as a woman. The year is 1850. An American adventurer named Shelmerdine falls off his horse, lands face-to-face with Orlando, now dressed in mid-Victorian blue-and-green plaid. This time it’s the man who begs Orlando to come with him, to America, to the future, to another shore. “You can stay and stagnate in the past,” Shelmerdine says, “or leave and live for the future!”

“When’s it going to begin?” Orlando asks. “Today, or is it always tomorrow?”

The southwest winds come, and Shelmerdine leaves as planned. Orlando stays, resolute in her place. In a world of false dualisms, tasting both is its own freedom.