Shock Value

By Laurie Stone

The Piano Teacher, dir. Michael Haneke, 2001

Shock Value

Michael Haneke’s The Piano Teacher confronts sex and desire with candor not analysis

By Laurie Stone

July 28, 2024

When The Piano Teacher was released in 2001, I thought, Wow, what a great movie. I thought, This movie will stay with me. Michael Haneke knows how to tell a story about women and sex—just the facts, without interpretation. He knows that inside the head of every woman is a porno booth flashing scenes from The Story of O. Even women who pin their hair back severely, wear achingly unadorned skirts and sweaters, and teach piano with crushing nastiness in a fussy Austrian music conservatory. Especially those women.

![]()

![]()

Psycho, dir. Alfred Hitchcock, 1960

Was I shocked? Maybe. Or maybe shocked isn’t the right word. Maybe something closer to amazed to see a rock moved aside, revealing a secret that everyone pretends is theirs alone. At the time, I wrote about the movie in a notebook. It was more or less a list of moments meant to stop us in our tracks and pump blood into our imaginations.

The scenes on this list included the piano teacher, Erika Kohut—played with stunning and inscrutable hauteur by Isabelle Huppert—sitting on the edge of a bathtub, holding a hand mirror and cutting her vagina with a razor blade. Erika climbing on top of her mother (Annie Girardot), with whom she shares a bed, and kissing her mouth while shouting, “I love you.” Erika holding a cum-soaked towel to her face in a porn booth while feeding coins into a video machine. Erika skulking around a drive-in cinema, where she spies on couples having sex, and where, hearing a woman reach orgasm, she squats beside the car and pees. Erika depositing broken glass in the coat pocket of a female student she’s become jealous of. Walter (Benoît Magimel), Erika’s student and love interest, growing increasingly disgusted and mocking as he reads aloud Erika’s directions for how to control and beat her.

The great pleasure of the movie—as well as other emotions it stirs—is its refusal to analyze or judge the characters’ actions. In the movie, this happens and then that happens, and then Erika stabs herself in the shoulder with a kitchen knife and walks on. Do the characters learn anything? Doubtful. Does the viewer learn anything? Yes, the viewer learns maybe you don’t want to go on living with Mom, especially if she rips up your clothes and considers you a whore for even thinking about sex. Maybe you don’t want to share Mom’s bed, even if she blames you for her boredom and loneliness and resents you for having a life—or at least a youth she can’t steal.

President John F. Kennedy, First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy and Texas Governor John Connally ride in a motorcade in Dallas on November 22, 1963

Haneke wrote the screenplay based on the 1983 novel by the Austrian writer Elfriede Jelinek. The book is written in almost the opposite spirit of the film. Jelinek is sniffing around all the time for social origins and psychological causes for the behaviors she reports. I find her prose hard to read. I don’t care—any more than Haneke does—why people do the things they do, or attach causes to outcomes that are mysterious. I don’t care because origin stories tend to be untrue or unprovable, plus they’re always formed when looking back, as if an endpoint must harbor a teleological arrow for how it was always going to turn out.

The other night when I rewatched the film, I found it just as brilliant as I had the first time, and almost immediately another thought formed: This movie is Psycho. I mean, think about it. The mother-and-child incestuousness. An overbearing and sexually punishing mom combined with a frozen offspring who is subject to violent eruptions. It would have been comforting to see Mother Kohut wind up mummified in a rocking chair beside Mother Bates.

As Psycho floated into my thoughts, it struck me that that movie, released in 1960 and upending the narrative in ways we’d never seen before, prepared us for the Kennedy assassination three years later. I mean, it prepared us for a bolting shock coming out of nowhere. A deadly knife in a motel shower, an ending arriving nearly at the beginning of a story that ushered behind it a progression of other endings in the movie. In our society as well.

The first shock can never be repeated. After the first shock, you get aftershocks, and aftershocks are in a different genre. First shocks tilt the world on its axis. You think, If this can happen, anything can. First shocks combine horror with freedom, and not the kind of freedom you always want. The kind of freedom that leaves you cold on a rock ledge, realizing that when you die, you die alone.

“Haneke’s camera makes the strange ordinary, remaining beautifully and oddly serene amid all the mishegas going on around it.”

I wasn’t shocked the second time I watched The Piano Teacher, and I don’t think it was simply because I’d already seen it. Twenty-three years had passed. The first time I was in my fifties. Now I’m in my seventies. Comedy, according to the famous formula, is tragedy plus time, and I think this is true. I think it’s how experience comes to feel. In time, you see the world with a shrug at whatever fresh hell is being reported in the world. The shrug is not indifference. It’s a Jewish shrug that translates into: What, you expected something different?

In the way Psycho prepared us for the assassination of JFK, the assassination of JFK prepared us for the Watergate break-in in 1972—and by then the zeitgeist had absorbed the shrug. Few people have told the story of the Kennedy assassination with a comic edge. With Watergate, on the other hand, few people have reported the antics and bumbling of “the plumbers” without a comic dimension.

Twenty-three years after its release, The Piano Teacher didn’t migrate from tragedy to comedy. Rather, it’s become easier to see that the movie always contained a comic dimension. It was always more interested in the natural history of shock—in individuals and in society—than in human pathology. It wanted to think about what we can stand to look at as spectacle, including cruelty and helplessness. Comedy is about limits, not transcendence.

In one comic comparison, the parent-child crazy in The Piano Teacher is Psycho. In another one, according to this film, all romance in the heads of women is like junior high dating. Walter is the cocky pretty boy every girl wants, and he sets his sights on the mean teacher, who would seemingly be the hardest one to get. The joke is on him. Be careful what you wish for, mate. You have no idea what movie you’ve walked into.

![]()

Janet Leigh in Psycho

![]()

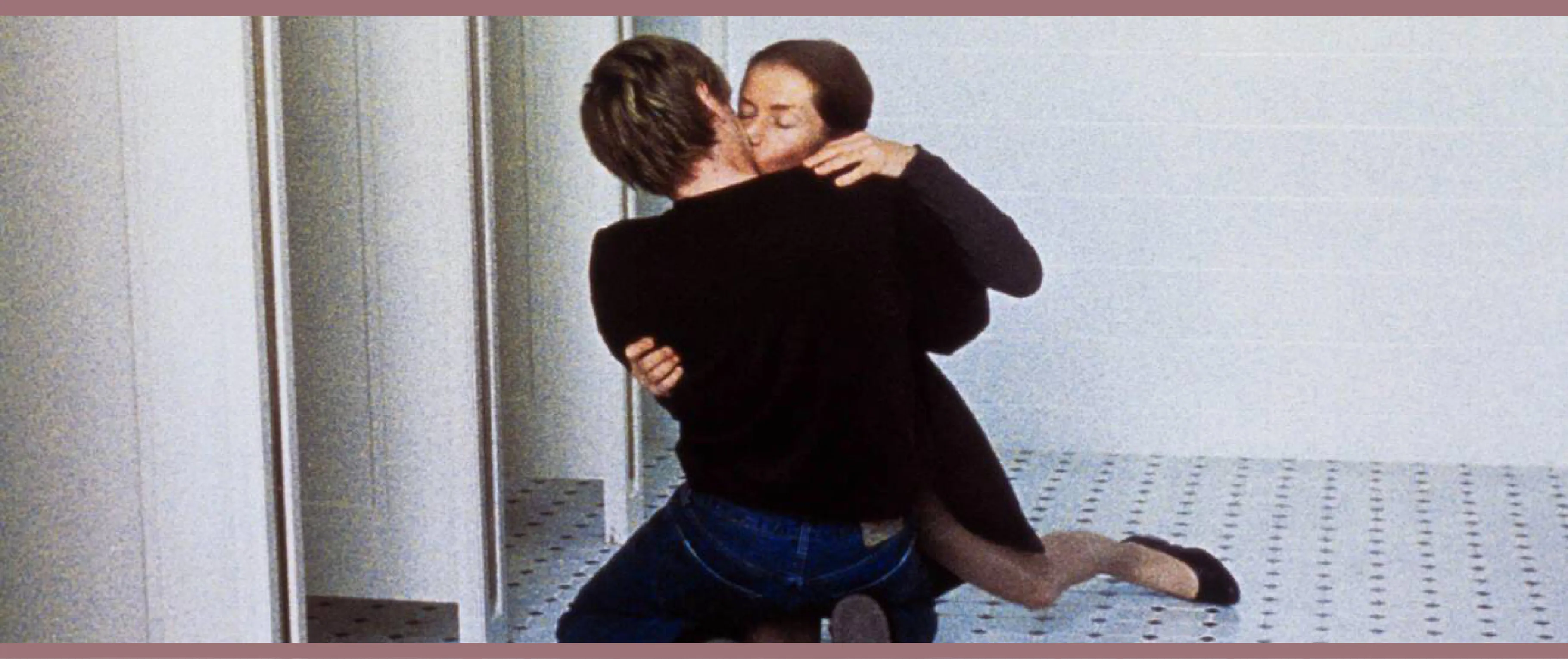

Benoît Magimel and Isabelle Huppert in The Piano Teacher

Nor does Erika. In the movie’s most difficult-to-watch scene—because it shows something sadly everywhere and all the time—Erika, frantic with longing, comes to Walter’s hockey practice and begs his forgiveness. What does she think she’s done wrong? Try to control the way she wants him to dominate her? She stands there almost innocently, with the awkwardness and incomprehension she feels most of the time, a child who has not been taught about the world. The begging doesn’t feel good, we see her realizing. It’s real humiliation, a surprising turnoff compared with the heat that shame arouses in sex fantasy.

Haneke has spoken in interviews about rejecting music in his films. He doesn’t want to wring emotion from a soundtrack. He wants the directing and acting to do that work. There’s lots of music in The Piano Teacher, of course, but it’s part of the business of the characters. Instead of a soundtrack, the film as a whole works as a piece of music, building momentum and depth through repetition and variations of dialogue and actions, allowing scenes to flow into each other by advancing the camera to a new location while a character in the previous location is still speaking.

To prompt surprise in drama, you have two choices. You can either make the ordinary strange or the strange ordinary. Haneke’s camera makes the strange ordinary, remaining beautifully and oddly serene amid all the mishegas going on around it. Often the camera looks away from the thing you might expect it to focus on. During a sex scene between Erika and Walter, we don’t see what they are doing. We see Walter’s back, fully clothed in hockey gear. When suddenly Erika rears up and vomits, the camera stays on her for a long time, until she’s washed her face and mouth.

“Be careful what you wish for, mate. You have no idea what movie you’ve walked into.”

In a scene between the two in a public toilet, when Erika tells Walter to do this thing or that with his penis, we don’t see the penis. Instead the camera plants itself in front of Walter’s face for what feels like forever as we watch his mouth twitch or his eyes wince in tiny ways. Or the camera watches Erika’s face go blank while, in her apartment, Walter continues to screw her after she’s said she wants him to stop.

In life, Haneke is saying, the strange and the ordinary have to coexist if people are going to go on. At Erika’s apartment, Walter beats her up, bloodying her face, and asks her, “Is this really what you had imagined?” After, glum and confused, she says no. The next day, at a recital, she nonetheless believes they are going to continue. Haneke’s camera talks to us casually, even at this juncture, and with a shrug.