Soldier of Fortune

By Steve Mears

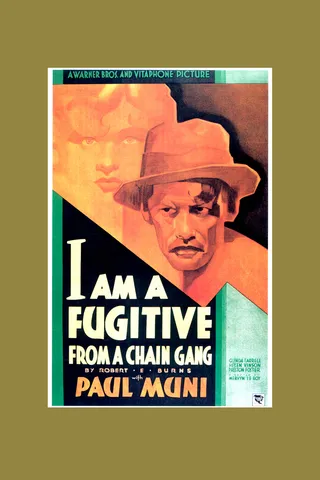

I Am a Fugitive from a Chain Gang, dir. Mervyn LeRoy, 1932

Soldier of Fortune

How Paul Muni’s devastating pre-Code portrayal of a marginalized veteran inspired real-life political reform

By Steve Mears

April 26, 2024

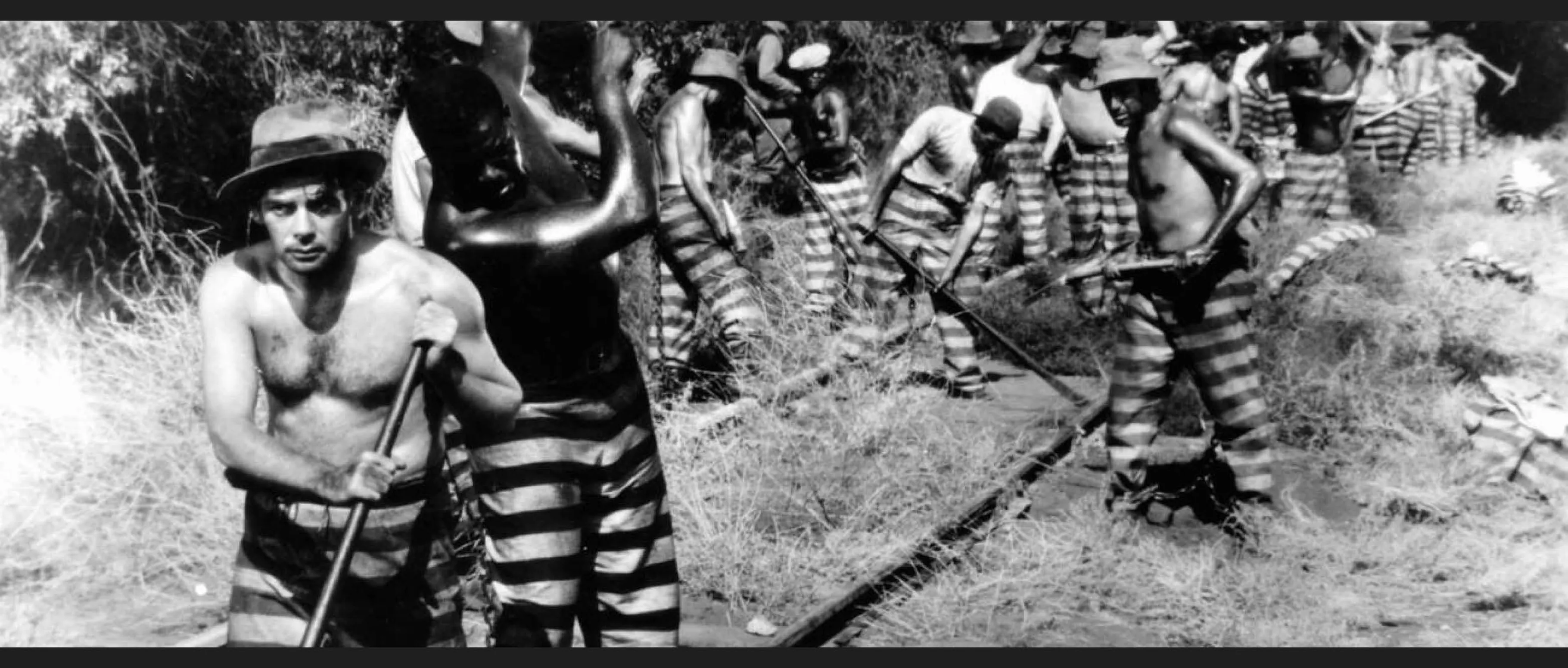

“I don’t want to be a soldier of anything,” asserts James Allen, a newly discharged sergeant whose World War I service has filled his head with bigger ambitions than reclaiming his prewar factory job. Like so many returning veterans, Allen (Paul Muni) wants to take the skills acquired in uniform—in his case, a knowledge of engineering—and use them for the betterment of himself and the society he fought to preserve. But before long, with jobs scarce and strapped for the cost of a meal, he finds himself a hapless accessory to a botched theft of five dollars from a hamburger stand, resulting in a draconian sentence of ten years’ hard labor. Now he is forced to rely on the combat-honed skills that he hoped never to reenlist.

From left: I Am a Fugitive from a Chain Gang poster; Mervyn LeRoy directing Paul Muni on the film’s set, 1932

Made in 1932, Mervyn LeRoy’s I Am a Fugitive from a Chain Gang confronts the plight of the forgotten ex-infantryman like few films of its era or any other. Long before its prison setting is introduced, Fugitive paints a desolate picture of the options available in civilian life to men forever marked by war. Notably, to audiences three years into the Great Depression, with little knowledge of PTSD (then referred to as shell shock), Allen would appear to be one of the lucky ones, with a home and job awaiting him on his return. But nine decades later, with more insight into the peacetime struggles faced by veterans (including those of recent wars), we see Allen’s situation differently: He is expected to resume work the very day after coming home, with no time to readjust to a life that must seem alien to him now. His brother is patronizing and his boss supercilious; only his mother listens to him. As he surveys the cheerless office to which his future has been consigned, a sudden blast startles him; his boss haughtily remarks that such things shouldn’t scare him now, but we see the terror behind his eyes when he replies, only half-jokingly, that the noise sent him “looking for the nearest dugout.”

“Even Cool Hand Luke seems romanticized next to LeRoy’s archetype.”

Learning that dynamite (which foreshadows his second escape from the chain gang) had been detonated as part of a construction project, Allen is reinvigorated: This is what he wants to do with his life. Like another case study of postwar frustration, James Stewart’s small-town martyr in It’s a Wonderful Life (1946), Allen yearns to build bridges, skyscrapers—monoliths of modernity and progress—and the impediments to his doing so are even more tragic for the good intentions behind them. “No one seems to realize that I’ve changed, that I’m different now,” he tells his bewildered family. “I’ve been through hell!” Drawing a direct parallel between the stultifying regimentation of the army and the oppressive monotony of his days at the plant (“I don’t want to spend the rest of my life answering a factory whistle instead of a bugle call”), he strikes out on his own.

Unsurprisingly, Allen’s efforts come to very little. Despite his aptitude and tenacity, there are just too many former doughboys and not enough jobs; the last spot on a work crew always seems to go to the man ahead of him in line. In one of the most heartbreaking scenes of 1930s cinema, he tries to hock his Belgian Croix de guerre medal, but the pawnbroker callously shows him dozens like it in a case. The symbol of his sacrifice proving worthless on the free market, he winds up in a flophouse, where an error in judgment finds him unwittingly involved in a robbery, and soon after, fitted for leg-irons.

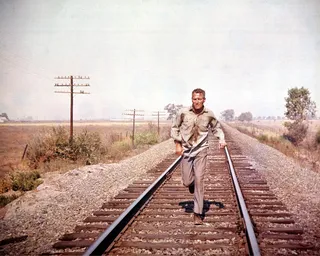

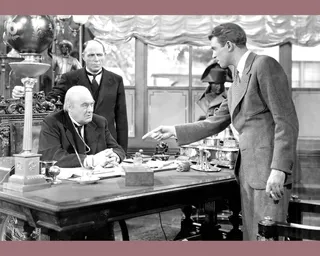

From left: Cool Hand Luke, dir. Stuart Rosenberg, 1967; It’s a Wonderful Life, dir. Frank Capra, 1946

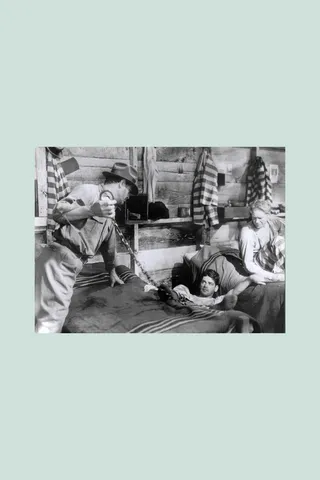

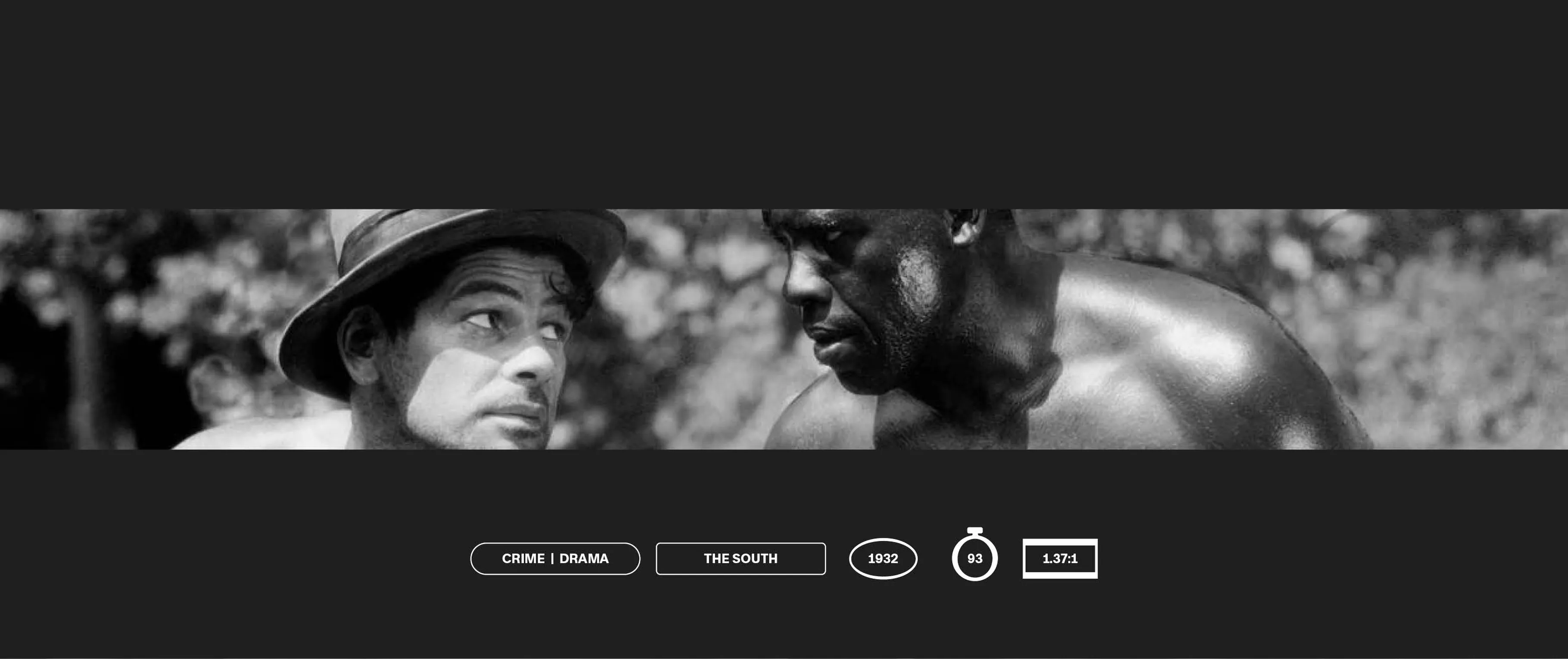

Fugitive’s pre-Code status becomes manifest in its prison sequences, especially those involving corporal punishment of the multiracial covey of convicts (who are segregated in bunk rooms and the mess hall but integrated during work hours). The lash marks visible on their backs, the annihilation of their agency (they must ask permission to wipe sweat from their foreheads) and the defeatism central to their outlooks (“There’s just two ways to get out of here: work out and die out”) are as horrifying as anything found in more recent releases. Even Cool Hand Luke (1967)—made 35 years later, in the last full year of the Code’s regime, before it gave way to the rating system still in place today—seems romanticized next to LeRoy’s archetype. Indeed, the filmmaker deserves much more credit for fine-tuning and blending two nascent genres that would dominate the decade to come: prison movies (owing much to George Hill’s epochal The Big House [1930], ground zero for nearly every trope about life behind bars) and the pungent gangster cycle, which LeRoy partly inaugurated with Little Caesar (1931) and whose themes of crime in the absence of gainful employment and evading captivity lent themselves handily to films about incarceration. To this mix he added the concern for social welfare that would prove his auteurist signature, notably in the harrowing lynch-mob drama They Won’t Forget (1937).

Like that film, Fugitive takes place in the Deep South and presents a web of institutional corruption where members of humanity’s lowest caste are subject to whatever passes for justice at the time, and authorities’ actions are guided more by optics and personal grudges than a sense of fairness. Allen’s story was closely inspired by the case of Robert Elliott Burns, a troubled veteran and drifter whose involuntary role in a grocery-store holdup earned him a similar sentence on a Georgia chain gang. Like Allen, Burns managed to escape and forge a successful life for himself in Chicago, but a letter likely penned by his vindictive wife saw him recaptured and extradited to Georgia, where broken promises from officials and denial of parole forced him to execute an even more daring escape. That’s where their narratives diverge: Burns’s reports of his brutal mistreatment by the justice system earned him renown as a writer (and inspired this motion picture). The controversy sparked by his memoir led to frequent lectures in which he recounted the horrors of chain gangs to an increasingly outraged public; ultimately, Georgia Governor Ellis Arnall commuted his sentence to time served and inaugurated widespread reforms on the state’s prison system. A 1987 TV movie, The Man Who Broke 1,000 Chains, tells Burns’s story without a pseudonym; he’s played by a young Val Kilmer.

From left: The Man Who Broke 1,000 Chains, dir. Daniel Mann, 1987; a shackled Paul Muni in I Am a Fugitive from a Chain Gang

With respect to Kilmer, who brings commitment and compassion to the role, Muni’s portrayal of Allen is definitive. Born Frederich Meshilem Meier Weisenfreund in Galicia, then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire and now Ukraine, he grew up speaking Yiddish and acting alongside his parents, devising elaborate makeup looks to play old men from the time he was a preteen. His early performances, particularly this one and the title role of Scarface (1932), a character modeled on Al Capone, exhibit an urgency and unmistakable if unquantifiable foreignness rare in studio-era Hollywood. By the end of the decade, Muni had switched gears and become known for biographical dramas like his Oscar-winning The Story of Louis Pasteur (1936). Heavy greasepaint and capital-A acting would prevail in these films, which brought the studio more prestige than revenue; as mogul Jack Warner famously observed, “Every time Paul Muni parts his beard and looks through a microscope, we lose a million dollars!”

But perhaps the most resonant line reading of Muni’s career is his hushed articulation of Fugitive’s last two words, voiced unseen from the shadows to the lover he’ll never meet again, who pleads to know how he lives as a wanted man: “I steal!” While society elected to deal with the sudden glut of returning veterans by denying them their liberty and exploiting them for free labor, Allen has rejected that framework, but in so doing has condemned himself to a life outside the law. The state has taken an innocent man and made him what it was put in place to rehabilitate: a hardened criminal, neither a soldier of war nor a soldier of peace but merely a soldier of survival.