The Architecture of Sound

By Alistair Tremps

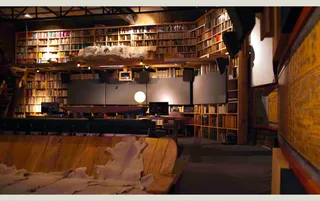

Splendor Omnia studio in Tepoztlán, Mexico

The Architecture of Sound

In Tepoztlán, Mexico, idyllic postproduction oasis Splendor Omnia gives rise to some of cinema’s greatest soundscapes

By Alistair Tremps

November 22, 2024

Biophilic design is the practice of adding plants to the workplace in the belief that humans are instinctively attracted to nature and that spending time with plants and animals reduces stress, improves health and boosts productivity—encouraging artistic endeavor, among other things. It’s a theory being put into practice by award-winning filmmakers Carlos Reygadas and Natalia López Gallardo, who have built a verdant postproduction facility specializing in sound approximately 90 minutes from Mexico City. Nestled in the mountains above Tepoztlán, the place even has a dreamy name, Splendor Omnia.

![]()

The book-lined studio at Splendor Omnia

![]()

Sound of Metal, dir. Darius Marder, 2019

Since it opened in 2011, Splendor Omnia has helped hone some of the greatest cinematic soundscapes of the past decade, including Darius Marder’s Oscar-winning Sound of Metal, Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s Memoria and Dea Kulumbegashvili’s San Sebastian International Film Festival Best Film–winner, Beginning.

Go onto the Splendor Omnia website, and one of the first images is of people making bread at a table filled with fresh fruits and vegetables. The impression is more Japanese spa than film facility. The accompanying text describes the place as “one of the most beautiful mountain ranges in the world…the climate is always mild and pleasant all year round.... Our buildings are made of wood, earth and hay...we care about serving food of the best quality, not industrialized.... For lodging, we have very spacious bungalows in the middle of the forest.” Just before you work out how to spend all your savings to book a weeklong retreat in this paradise, it finally mentions, almost as an aside, “At Splendor Omnia, we have thought carefully and worked hard to achieve image and sound post-production studios of world-class technological quality and technical expertise.”

As I drive up toward Splendor Omnia, on my way to meet Reygadas and López, I am forced to a stop as two bull calves engage in playful combat in front of my car, one pushing the other back with latent aggression. It reminds me of a scene from the final minutes of Reygadas’s 2018 existential Western Our Time, in which, as the mist clears, two bulls in a herd lock horns, at first testing each other playfully, but escalating toward tragedy, with one of them plunging over a cliff. Luckily for the losing calf today, the only real damage is a couple of dents in the bodywork of my battered SUV. I imagine how angry I would be if two young kids fighting did the same damage.

Our Time, dir. Carlos Reygadas, 2018

After parking under a canopy of old-growth trees surrounded by butterflies, the silence is punctuated by birdsong and an occasional dog barking in the distance. Over a cup of ginger tea on a wooden terrace overlooking the facilities, I chat with López, who started her career working as an editor with Reygadas and similarly uncompromising directors Lisandro Alonso and Amat Escalante. She tells me that the studio’s founding mission was to nurture filmmakers and allow them the space to be creative at a tense and fragile moment in a film’s life, when directors are down to their last remaining shreds of energy, budgets are dwindling, and they are facing doubts about whether their work will resonate with an audience. “Your entire day is focused on just one thing,” she says, referring to sound design. “Having that space to reflect on the process helps to make this a different experience, which I believe is imprinted on the film.”

The philosophy of Splendor Omnia can be found in the movies that made Reygadas one of the leading art-house figures of the Mexican New Wave, which at the turn of the millennium produced a crop of luminaries, including Alfonso Cuarón, Alejandro González Iñárritu and Guillermo del Toro. The Screen Daily review of his enigmatic, award-winning debut Japón (2002), about a man in crisis preparing for his own death,, posited that it “builds up an earthy, visceral portrait of rural life…The sound design is also exceptional, evoking the subtle tapestry of noises to be heard in even the most remote and peaceful location.” Reygadas’s third film, the Cannes jury prize–winner Silent Light (2007), a spiritual exploration of faith and mortality, had The Guardian enthusing about its “sublime, meditative moments: moments of pure, unapologetic visual ecstasy that come close to repealing the cinematic laws of gravity.”

Daily life at Splendor Omnia resembles a retreat in paradise

“I’ve always had a soft spot for sound,” Reygadas explains as we tour the facility, “because it is more closely linked to the physical world, it still depends on the reverberation of space, on how it reacts with different materials.” He argues that sound could be considered even more critical to cinema than vision in creating the reality and emotions conveyed on film. If you plan to build a sound-mixing facility, choosing a location far from the hustle of city life offers an immediate advantage: “Our most abundant resource was earth, which has less reverberation than any other natural material,” Reygadas explains. “We built here using earth, wood and other local materials, and our outside noise pollution is practically non-existent.”

Starting from scratch, he and López erected a sound-mixing room with an ideal acoustic shape, the walls and ceiling curving like an old-fashioned loudspeaker. Instead of the soundproofing foam found in studios from London to Lagos, insulation behind the console in Splendor’s theatrical mixing room comes from an array of bookshelves, with hundreds of tomes—legal volumes, philosophical treatises, literary classics—carefully arranged in a zig-zag pattern. The goal of the space is technical excellence and also inspiration—the sense of envelopment and connection to nature and art get my creative juices flowing as I stand there. Reygadas smiles witnessing my awe.

Scattered around the sprawling campus 6,500 feet above sea level are the mixing rooms and accommodations built from volcanic rock, stone salvaged from 19th-century colonial buildings, weathered timber and slate tile roofs. I’m particularly taken by the Frank Gehry-like curves on the roof of Splendor’s stables, which double as a water-collection system, channeling seasonal rainfall into the enormous underground cisterns that allow the facility to survive partly off the grid. It all blends seamlessly into the surrounding forest and rock face. Everything feeds into the code they are governed by.

“Working at Splendor is more like Vipassana meditation or a runner’s high...”

“We try to avoid working with a ticking clock or in a commodified atmosphere,” says Reygadas. “I believe that the current climate of competition, of productive and financial pressure, is a constant source of existential anxiety, and we try to keep that at bay.”

But this remote, wild setting also has a less convenient side, which means it is not for everyone. Thunderstorms are nearly daily occurrences for several months of the year, and power cuts are a fact of life. Plus, there’s the occasional scorpion in your bungalow. But Reygadas believes in the silver lining. “In order to truly appreciate an atmosphere of peace, sometimes it needs to exist in counterpoint to something else, a bit like the contrast between the bitter cold of a northern European winter and a warm pub with a roaring fire. Appreciating the violence of a torrential thunderstorm or being aware that we are surrounded by wildlife can make you feel more alive,” he says. “We try to counteract those elements without eliminating them, and of course, it also depends on one’s personal disposition: Some people are addicted to city life, but most need a break from it.”

The tour of the facilities made me think about music producer George Martin on the volcanic island of Montserrat in the Caribbean. Years after he helped craft the sound of the Beatles he fell in love with the landscape, the people and the island’s lifestyle, and opened a state-of-the-art recording studio there in 1979. Until it was wiped out by hurricanes, volcanic eruptions and changes in the music business, a who’s who of 1980s pop and rock artists recorded at Martin’s AIR Studios Montserrat, where the island’s beauty and isolation helped the Rolling Stones, Paul McCartney, Dire Straits, The Police, Elton John and Black Sabbath produce landmark albums.

Likewise, director Darius Marder believes that the environment at Splendor Omnia helped foster the remarkable Oscar-winning soundscape of Sound of Metal. The film tells the story of a musician, played by Riz Ahmed who, upon losing his hearing, decides to have cochlear implants against the advice of his peers. Viscerally, the sound design helps us experience what the protagonist hears and feels, with its occasional dropouts and overbearing ringing sounds. “Sound of Metal required an unusual level of focus,” recalled Marder of the weeks and months he spent there with French sound designer Nicolas Becker. “Every element at Splendor reinforced the edict that a technical, creative experience is not just the minutiae of what happens in the studio and not simply the march towards a product; it is born of a total experience.”

From left: Beginning, dir. Dea Kulumbegashvili, 2020; Silent Light, dir. Carlos Reygadas, 2007; Memoria, dir. Apichatpong Weerasethakul, 2021

Sound engineer Carlos Cortés Navarrete, who shared the Academy Award for Best Sound in 2020 with Becker and others for their work on Marder’s film, says that working at the Tepoztlán retreat is an intensive process that can become overwhelming, “but it is rewarding because of the deep dive it allows into the film.” After a couple of days building rapport with the project and the visiting creative team, Navarrete explains, the work becomes a conversation between the filmmakers and the facility owners: “Ultimately, we walk that path and discover it together, and the isolation and concentration make that possible.” Many of these discussions would often happen around the dinner table. Frequently served up are enfrijoladas, eggs from Splendor’s own hens (which run amok as we tour the grounds), handmade corn tortillas and salsa—home-cooked dishes with deep roots in the local community.

Compared with the stop-and-start dynamic at comparable sound facilities in urban settings, Navarrete adds, “working at Splendor is more like Vipassana meditation or a runner’s high, in which continuity and complete immersion enable you to take the work further, as you inhabit a space of work and life at the same time.”