This Means War

By Christina Newland

Hearts and Minds, dir. Peter Davis, 1974

this means war

Before Hollywood began processing Vietnam, a spate of independent films—including the Oscar-winning documentary Hearts and Minds—contended with the conflict’s devastating impact

By Christina Newland

June 3, 2024

When the independently made Vietnam War film Hearts and Minds won the Academy Award for Best Documentary Feature in 1975, it happened during a ceremony that featured two radically different viewpoints on the ongoing war. On one side was the older, more conservative generation, embodied by one of the evening’s hosts, Bob Hope, whose USO tours had entertained American troops in Vietnam. On the other, the attitude held by Hearts and Minds itself, a muscular criticism of U.S. foreign policy. In a coup of irony, Hope actually makes a cameo in Hearts and Minds as the entertainment at a White House dinner for returning POWs in 1973, where one of his awful wisecracks is met with resounding boos. “This is what I like,” he quipped. “A captive audience!”

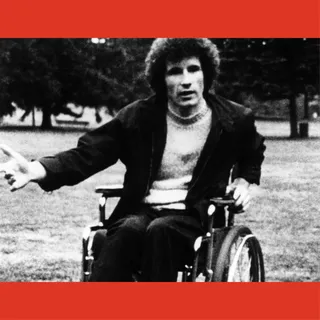

![]()

A Vietnam War veteran in Hearts and Minds

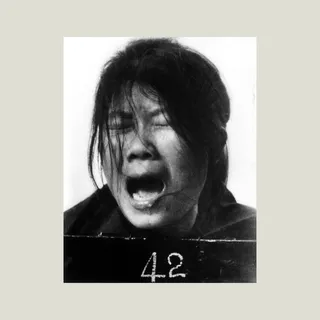

![]()

A victim of the South Vietnam secret police in Hearts and Minds

So when the film’s director, Peter Davis, and famed counterculture producer Bert Schneider (whose BBS Productions was also behind New Hollywood classics Easy Rider and Five Easy Pieces) came onstage to collect their award, a pivotal moment for anti-war politics flashed into the mainstream. Schneider read out a message of peace from “the Vietnamese people” (specifically, a wire from the delegation of the Provisional Revolutionary Government of the Republic of South Vietnam to Paris). During a television broadcast watched by an estimated 48 million people, one of the films most openly critical of American militarism and foreign policy won the industry establishment’s highest honor. To understand how a radical film like Hearts and Minds ascended to this lofty stature in American culture—and why it still resonates today with the need to speak truth to power—it is useful to understand the climate in which it was produced.

American society was tearing itself in two over the domestic and foreign turmoil under Richard Nixon’s presidency. From the women’s movement to civil rights and beyond, the political rift was not just a generation gap but a chasm of class, values and geography (the coasts and the heartland often failed to see eye to eye, although there were pro and anti-war factions all over the nation). These differences were pulled into even starker relief in their attitudes to the Vietnam War. The conflict-supporting members of Nixon’s silent majority might have found the truth—namely, that the hippies and peaceniks were probably on the right side of history—a bitter pill to swallow.

“With no voice-over, the film allows its horrific imagery to speak for itself.”

Hearts and Minds’ title was borrowed from President Lyndon Johnson’s mild-sounding yet profoundly misleading assurances that the conflict in Southeast Asia could be won through diplomatic efforts that appealed to the “hearts and minds” of the Vietnamese people. In the midst of America’s cold war, Johnson first mentioned this more peaceful tactic at a dinner in 1965 and would repeat it often in subsequent public pronouncements, the phrase becoming a kind of mantra. All the while, violence intensified in Vietnam. By the time Hearts and Minds was released in 1974, Johnson’s mantra seemed coined for a long-distant past: Ultimately more bombs were dropped on a country slightly larger than New Mexico than had been deployed in the entire aerial bombing of Europe during World War II, while history has shown that there were also illegal, covert bombings of neighboring countries Laos and Cambodia.

The film mixes archival footage, news imagery and interviews with politicians, military figures, Vietnam War veterans and their Vietnamese counterparts and victims. Davis also cuts directly between Nixon talking up the continued need for the war and footage of the consequences of that aggression—scenes of violence and death. With no voice-over, the film allows its horrific imagery to speak for itself. But there is no lack of ideology in the arrangement of these images: The results are explicitly anti-war.

Hearts and Minds may be a partisan film, but it is an effective one, released to a war-weary domestic audience primed to absorb its message. In 1974 Rex Reed described it as “the only film I have ever seen that sweeps away the gauze surrounding Vietnam and tells the truth.” (When it was revealed that the New York Daily News had pulled his positive review, the film became an even greater talking point.)

Hearts and Minds stands above many of the narrative Vietnam films that would come later, largely because it does not prioritize an American perspective over that of the Vietnamese. Instead it offers a mosaic of viewpoints, from anti-war activists and POWs to the memorable moment in which General William Westmoreland, commander of U.S. forces in Vietnam from 1964 to 1968, claims that “Orientals” do not value life the way Westerners do. Davis juxtaposes the general’s prejudices with footage from a funeral, at which a grieving Vietnamese woman attempts to throw herself into a grave, and the film implies that racism and dehumanization played a significant role in the war effort and in some Americans’ indifference toward the destruction of Vietnam.

It wasn’t until after the last chopper left Saigon in April 1975 that the first mainstream features were made about the war; some earlier, more marginal works arrived while it was still raging on. The films on our list—ranging from radical indie documentaries to Oscar-sweeping classics—offer distinct cinematic visions and varied stylistic approaches to the damage inflicted on every side of the conflict and will leave you questioning what it means to love your country.

![]()

Apocalypse Now, dir. Francis Ford Coppola, 1979

![]()

The Deer Hunter, dir. Michael Cimino, 1978

In the Year of the Pig, dir. Emile de Antonio, 1968

A cerebral, visually striking documentary borrowing from the Neo-Dada and Pop Art vernaculars that De Antonio had emerged from—he was well acquainted with John Cage, Andy Warhol and Robert Rauschenberg—and one of the earliest documentary films to tackle the Vietnam War. Casting a a keen eye on the historical backdrop of the conflict, In the Year of the Pig seeks to inhabit the Vietnamese viewpoint while addressing the French colonizers and American foreign policymakers who set events in motion. With colorful visual juxtapositions and an elliptical editing style, the film is a politically strident history lesson as well as a gem of the counterculture spirit.

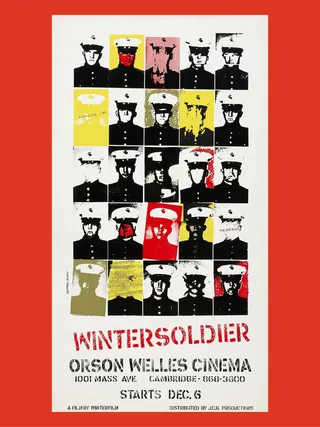

Winter Soldier, dir. Winterfilm Collective, 1972

In 1971, Vietnam Veterans Against the War met at a Detroit hotel to participate in the Winter Soldier Investigation, to convey and collect eye-witness testimony from American soldiers who had witnessed and participated in atrocities against civilians in Southeast Asia. Interviews were shot on borrowed stock by a group of activist filmmakers including Barbara Kopple, who would later win an Academy Award for her lyrical, left-wing ode to a coal miners strike in Harlan County U.S.A. (1976). The power of Winter Soldier lies in its raw simplicity: first-hand accounts by more than two-dozen young, haunted vets who detail acts of torture, killing and mutilation and the burning of homes and villages. Most shocking of all is the tacit support of these outrages by the top ranks of the military.

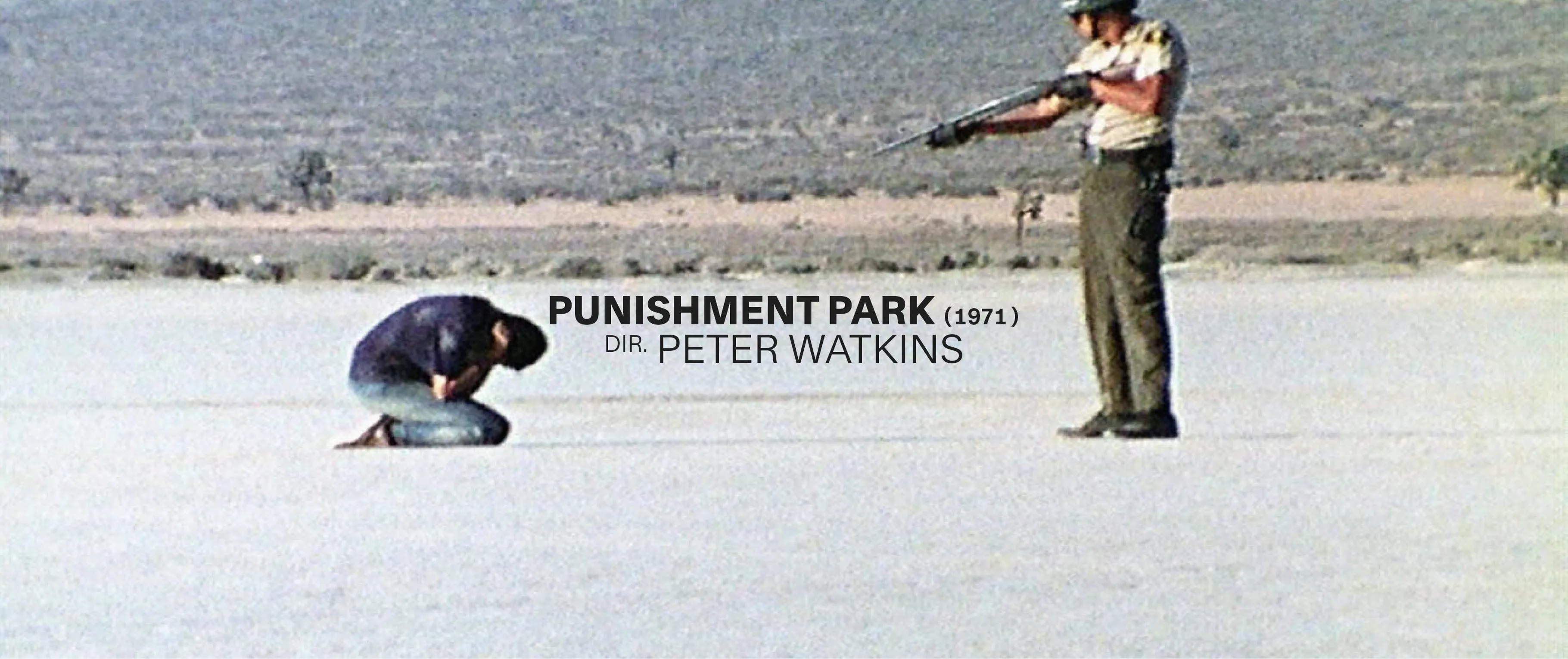

Punishment Park, dir. Peter Watkins, 1971

British-born filmmaker Peter Watkins brought a fresh perspective to fictionalizing the conflict with a pseudo-documentary style conjuring dystopian realities that appear unnervingly truthful (Nixon’s never-realized Huston Plan did consider detaining domestic radicals in internment camps). Watkins used a similar style for The War Game (1966), his imagining of a nuclear winter in the U.K. In Punishment Park, we visit the “Bear Mountain National Punishment Park,” an internment camp for anti-war activists, Black Panthers and other perceived enemies of the state who are hunted for sport in the searing heat of the Southern California desert—all presented by Watkins as found footage.

![]()

Coming Home, dir. Hal Ashby, 1978

![]()

a poster for Winter Soldier, dir. Winterfilm Collective, 1972

Coming Home, dir. Hal Ashby, 1978

Hal Ashby, who’d made films as diverse and distinctive as Shampoo, The Last Detail and Harold and Maude, puts the countercultural cat among the pigeons again with this domestic take on the trauma and social upheaval in the wake of the war. Coming Home is a curious, thoughtful emotional drama about a returning vet and a VA volunteer. The film’s uniquely feminine viewpoint is largely due to Jane Fonda’s involvement, not just in a leading role as a military wife working in a hospital for returning soldiers, but also from a production standpoint: She developed the film through her production company, IPC Films, or Indochina Peace Campaign. While her uptight officer husband (Bruce Dern) is off at war, Fonda’s Sally slowly falls for a former high school classmate (Jon Voight), a weary, newly disabled vet who must learn to face the world in a wheelchair. In the vein of a World War II homefront weepie about the women left behind—but with a strong anti-war sentiment and powerful writing and performances that clinched Oscars for Fonda and Voight.

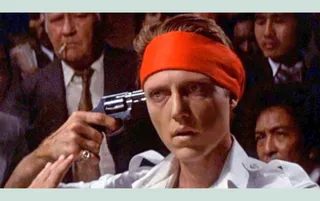

The Deer Hunter, dir. Michael Cimino, 1978

Michael Cimino’s sometimes myopic take on working-class American men and the damage they suffered as a result of their wartime experiences, The Deer Hunter is a sweeping epic with a palpable realism that reveals the shattered psyches of those who fought and lived through Vietnam. This swan song to blue-collar youth lost at war features memorable performances from Robert De Niro, Christopher Walken, John Cazale and Meryl Streep. Following Western Pennsylvania steelworkers into the heart of the conflict and their traumatizing time as POWs, Cimino’s film has been criticized for its lack of historical validity but speaks to U.S. concerns over a generation caught under the military-industrial complex’s tank tracks. Walken’s Oscar-winning performance—and his Russian roulette scenes—may well be seared into the retinas of countless moviegoers.

Apocalypse Now, dir. Francis Ford Coppola, 1979

The bubbling cauldron of madness in Coppola’s opus seems to come closest to representing America’s catastrophic personal and moral losses during the protracted horror of Vietnam. Captain Willard’s (Martin Sheen) journey up the Mekong to find the AWOL Col. Kurtz (Marlon Brando, of course) was based on Heart of Darkness, Joseph Conrad’s novella set in the Congo Free State. (Coppola clearly saw parallels between contemporary U.S. imperialism and other forceful invasions of the past.) The director, who had already masterfully chronicled American ambition, fallibility and power dynamics in his first two Godfather films, applied Conrad’s colonial warning with gusto. The film’s notoriously treacherous production in the jungle co-starred bouts of severe illness and very odd behavior from certain cast and crew, resulting in a cockeyed masterpiece as feverish and terrifying as the experience of making it seemed to be.