Transformers by Trade

By Christina Newland

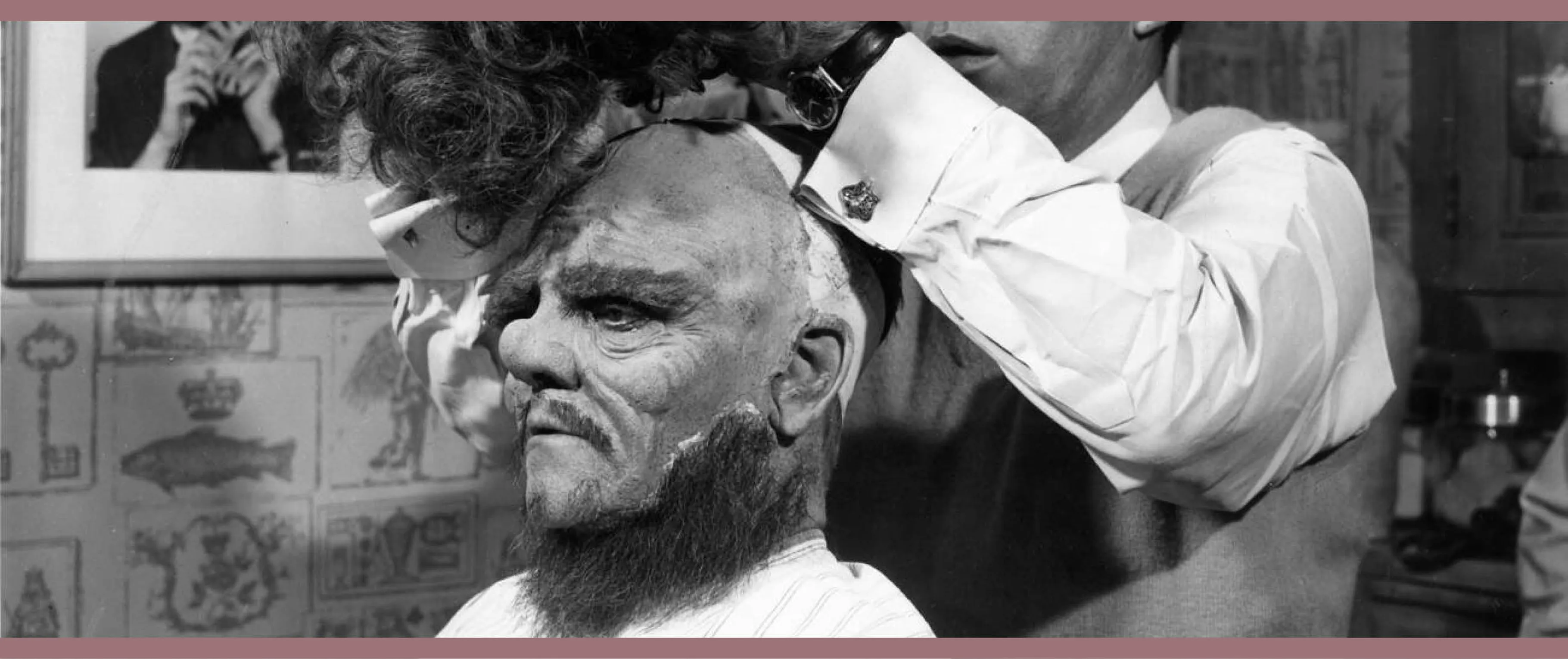

James Cagney as Lon Chaney Sr. (left) with makeup artist Bud Westmore on the set of Man of a Thousand Faces, dir. Joseph Pevney, 1957

Transformers by Trade

Spirit gum, wires, foam latex and hours of labor—why the traditional craft of practical makeup continues to thrive in the digital age

By Christina Newland

March 13, 2024

There are few below-the-line workers on a film production that wield such powerful yet underappreciated skills as those of the makeup artist. Aside from a few one-off honors, the first Academy Award for makeup didn’t come until 1965, nearly 40 years after the ceremony had been inaugurated. The one-off honor went to MGM makeup veteran William Tuttle for his prosthetics creations for 7 Faces of Dr. Lao. It wasn’t until 1981—and perhaps not coincidentally, the rise of the horror genre into the mainstream again—that an annual category was specifically dedicated to makeup and hair artistry.

From left: The Company of Wolves, dir. Neil Jordan, 1984; Ed Wood, dir. Tim Burton, 1994; Infinity Pool, dir. Brandon Cronenberg, 2023; Ginger Snaps, dir. John Fawcett, 2000

From the beginning of Hollywood’s Golden Age, in the 1930s, right into the 1980s, long hours in the makeup chair were de rigueur. The studio backlot was a surreal fiefdom of hierarchical power, from the head of the makeup department downward, where tasks from the pragmatic (fixing hangover skin) to the fantastical (airbrushing nearly 300 extras green for The Wizard of Oz) demanded equal importance—and skill. And that’s before we introduce the monsters.

Long before the advent of CGI or green screens, studio productions relied on practical effects, makeup and good old-fashioned insider tricks of the trade to produce their intended result, be it luminous film-star beauty or a gruesome mug. Universal Studios monster-maker and chief makeup artist Jack P. Pierce would force his stars—Lon Chaney Jr. among them—into four-plus-hour stints in the makeup chair. Using layers of spirit gum (a resin adhesive) and crinkled paper for aging effects, or collodion to create artificial scars and gashes, the old style of makeup tech may have been visceral, but it worked. (You need only look at Chaney Jr.’s famous father in The Phantom of the Opera [1925] to sense as much. Chaney Sr. was famous for devising his own makeup, and he achieved the Phantom’s look, still among the most notorious scares in cinema history, with a combination of contour shading, putty and painful wires hooked into the nostrils.)

Pierce created the makeup for Boris Karloff’s monster in Frankenstein (1931)—for which the makeup artist used a hybrid blend of rubber headpieces and gray-green greasepaint to achieve the look—as well as most of Universal’s 1930s creatures, including those in The Mummy (1932), The Invisible Man (1933) and Werewolf of London (1935). But Pierce was fired from the studio in 1946, possibly owing to his old-fashioned methods. By the time of Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein, in 1948, the more “modern” horror makeup that his successor, Bud Westmore, helped usher in became the new standard. The advent of foam latex, which allowed Westmore’s team to make monsters faster and quicker, also may have precipitated Pierce’s ousting.

The six-brother dynasty of makeup artists known as the Westmores—Mont, Perc, Ern, Wally, Bud, and Frank—understood the benefits of innovation. They populated nearly every major movie studio in Hollywood during its Golden Age, each running his respective makeup department, whether creating glamorous visages for a Paramount Pictures romance or gruesome mugs for a Universal horror. For the latter sort of production, second youngest brother Bud Westmore became the star. This was largely because he landed at Universal-International, the B-studio of dreams for an on-the-make genre artist. Handsome but dictatorial, Bud was known for his extreme vindictiveness on the lot.

Help came from beyond the makeup artist’s professional purview too. Before the Make-up Artists and Hair Stylists Guild, founded in 1937, prevented actors from doing their own makeup on set, Lon Chaney was known as the Man of a Thousand Faces for his innovative approach and skill at making himself gruesome. His son, best known for playing the title role in The Wolf Man (1941), had a less adventurous attitude toward makeup: By the time he made Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein, with its selection of all-star ghouls (the Wolf Man is reprised by Chaney Jr. here, complete with yak hair stuck to his face), he was in constant arguments with his makeup artists over the arduous and sometimes painful hours spent in the chair.

“Using layers of spirit gum and crinkled paper for aging effects, or collodion to create artificial scars and gashes, the old style of makeup tech may have been visceral, but it worked.”

In spite of these on-set difficulties, Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein became a much-imitated comedy-horror classic—perhaps the first of its kind in its hybrid blend of scares and laughs, a trend that reverberates in the modern-day likes of Scary Movie (2000) or The Cabin in the Woods (2011). The comedy duo would star in a series of spin-offs, including Abbott and Costello Meet the Killer, Boris Karloff (1949) and Abbott and Costello Meet the Mummy (1955), all under the careful brush-wielding dominion of Bud Westmore and company. The original film offered a template: It trades in an artful blend of both physical slapstick (Abbott and Costello’s calling card) and fast-talking verbal sparring. (Sample dialogue: “Go look at yourself in the mirror sometime,” Abbott says. “Why should I hurt my own feelings?” Costello responds.) And because it is poised on the line of self-awareness as a borderline loving parody of the 1930s Universal horrors, the cosmetics, too, are somewhat more exaggerated and pointed to for laughs.

In 1957 Bud Westmore was drafted by Mattel to design the makeup for its first Barbie; he borrowed the arched brows, catlike eyeliner and red lipstick that had defined mid-century femininity. That same year he headed makeup for the Lon Chaney biopic Man of a Thousand Faces, with James Cagney in the lead role. But by the 1960s, Westmore’s power at Universal was waning. As his younger brother, Frank, wrote in his 1976 memoir, The Westmores of Hollywood, Universal was “the last of the major studios to determine that it no longer needed a lavish old-time makeup department headed by a high-salaried, all-powerful autocrat.” The age of the powerful makeup czar came to a close, opening the door to younger creative outsiders who would continue to revolutionize throughout the 1970s and 1980s.

Dick Smith, the godfather of makeup behind The Exorcist (1973), was entirely self-taught. Tom Savini, the uniquely talented creator of horrific effects for films such as George A. Romero’s Dawn of the Dead (1978), served as a combat photographer in Vietnam before he found his place in makeup and special-effects work. Savini has spoken about his wartime experiences and their impact on his professional creation of bloody viscera. These next-generation freelancers operated within the world of practical effects and tactile innovation with prosthetics, eschewing the more hierarchical old-school world of the studio makeup department and instead specializing in specific skill sets. In Neil Jordan’s werewolf-horror The Company of Wolves (1984), for instance, makeup artist Christopher Tucker designed the grotesque transformation from man to wolf by using latex and dummies to fabricate the musculature of the transitioning beast. (It was Tucker’s work on David Lynch’s The Elephant Man (1980) that inspired the Academy to inaugurate a competitive category for Best Makeup in 1981.)

From left: Boris Karloff with makeup artist Jack S. Pierce, 1932; the wedding party scene from The Company of Wolves, 1984

Even in the 21st century, the spirit and passion for horror makeup as a practical art remains very much in existence. Contemporary directors who might have turned to digital effects for convenience are instead turning to the practical ones they were raised on, both for familiarity and for their texture of heightened authenticity. This has been true right up to the present, when David Cronenberg’s filmmaker son, Brandon, returned to practical effects for his bizarre body-horror Infinity Pool (2023). But this isn’t new: Even in the immediate wake of CGI’s widespread use in the 1990s, films from Ed Wood (1994) to Event Horizon (1997) utilized the handmade. In 2000 feminist cult-horror Ginger Snaps transformed its lead into a monstrous werewolf with the aid of prosthetics and laborious makeup by Paul Jones. Plus ça change: Just like Lon Chaney Jr., Boris Karloff and others before her, star Katharine Isabelle spent hours in the makeup chair, being fitted with blue contact lenses that hurt her, a facial prosthetic that triggered a persistently runny nose and fake blood that would take two hours to wash off. Before the final scene, where Isabelle’s Ginger turns on her sister, she fully transforms into a werewolf, gnashing her teeth as the facial prosthetic sprouts into a lupine snout, with old-style latex and trick editing enlisted to indicate the transformation as her humanity melts into full animalistic rage. Still, Isabelle claimed to have loved the experience, even when she was using dozens of cotton buds to prevent her nose from running under her prosthetic mask. When it comes to movie cosmetics, if beauty is pain, then ugliness is too.

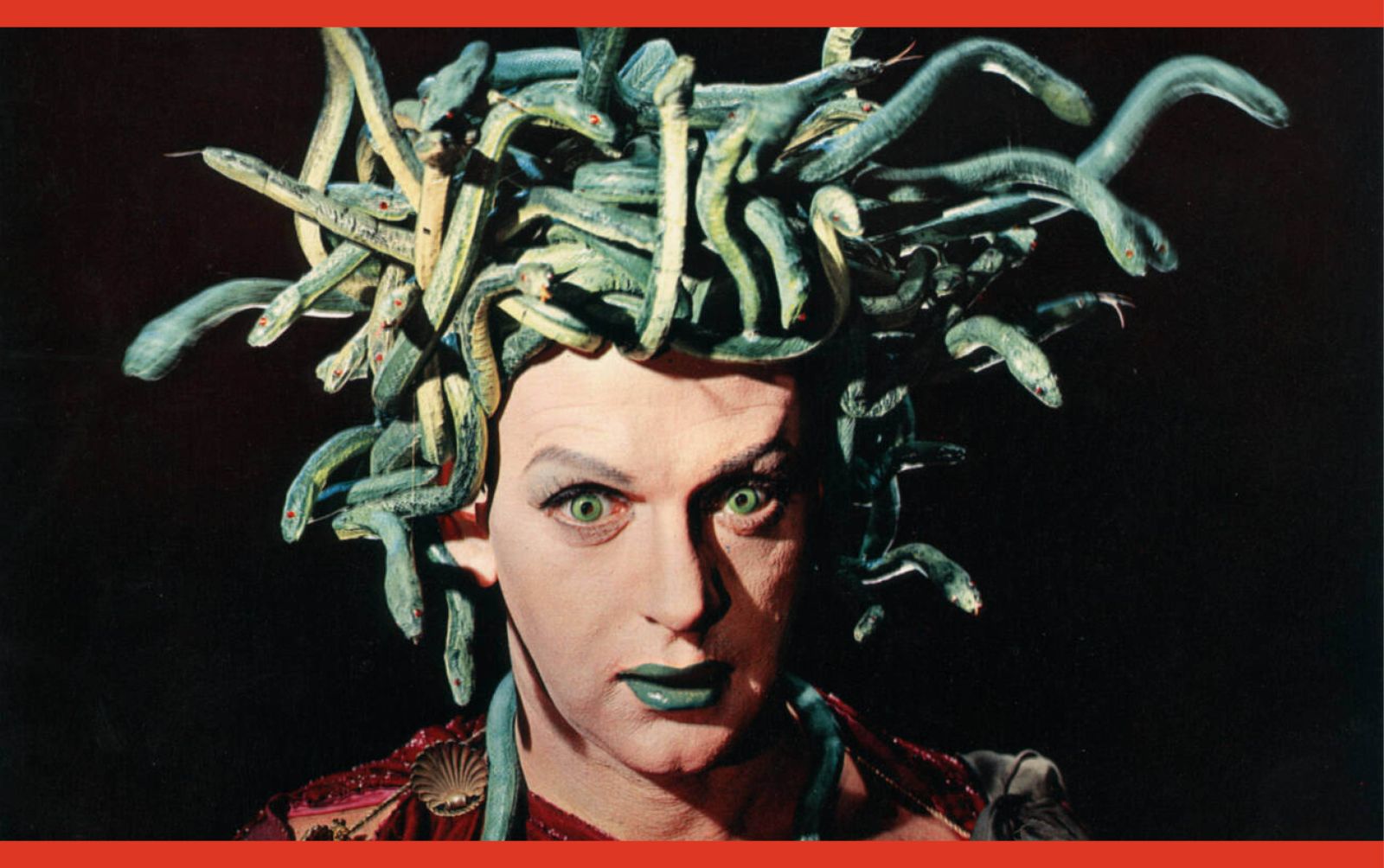

7 Faces of Dr. Lao, dir. George Pal, 1964