Truly Close Encounters

By Alex Hawgood

Close Encounters of the Third Kind, dir. Steven Spielberg, 1977

Truly Close Encounters

Recent headlines about extraterrestrial phenomena suggest the merging of cinematic science-fiction and real life

By Alex Hawgood

May 14, 2024

Last summer Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer sounded the alarm on alien attacks. “The American public has a right to learn about technologies of unknown origins, non-human intelligence and unexplainable phenomena,” the New York Democratic senator declared. Schumer was referring to the Unidentified Anomalous Phenomena (UAP) Disclosure Act of 2023, a remarkable piece of once unthinkable policy slipped into the U.S. Defense Department’s 2024 operating budget. In the proposed measure, the phrase “non-human intelligence” was mentioned not once but 22 times. One stipulation called for the government to take “physical possession of technologies of unknown origin or biological evidence of non-human intelligence” through power of eminent domain. Such objects are “what were previously described as flying discs and flying saucers,” the legislation noted with B-movie aplomb.

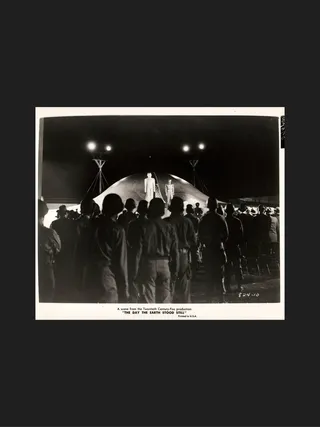

The sweeping urgency of Schumer’s message to the American people could have been ripped out of a film script. In fact, the speech brought to mind one immediate cinematic antecedent: the 1951 sci-fi classic The Day the Earth Stood Still, in which an alien emissary named Klaatu (Michael Rennie) lands in Washington, D.C., with an urgent call for intergalactic order. The film’s tagline is “From Out of Space...a Warning and an Ultimatum!”

Given these recent developments, sci-fi narratives, once dismissed as the stuff of crackpot conspiracies and feverish Hollywood imaginations, are receiving a more credulous reception on social media and in mainstream publications—even by Washington authorities. Articles in The New York Times have reported clandestine government investigations of unexplainable craft. High-ranking military veterans have testified to Congress that unidentified anomalous phenomena, or UAP—modern lingo for “UFO”—threaten the safety of America’s airspace. Last fall the Defense Department launched a “secure mechanism for authorized reporting” (an intra-military UAP hotline, if you will) and NASA appointed its first director of research for “observations of events in the sky that cannot be identified as aircraft or known natural phenomena—from a scientific perspective.”

From left: A New York Times headline from December 16, 2023; Asteroid City, dir. Wes Anderson, 2023

Of course the UAP Disclosure Act also had its detractors. And it has encouraged endless conspiracy theories about the government’s concealing information about alien existence, all flavored by a host of cinematic alien pop-culture references, from ’50s-era fluff like Plan 9 from Outer Space to 1990s The X-Files and all the way to Netflix’s recent 3 Body Problem. Though the measure won final approval with a bipartisan vote, a handful of influential Republican politicians with ties to the Defense Department (including Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell and Speaker of the House Mike Johnson) pulled the plug on the bulk of the bill, nixing legalese around eminent domain. One wonders whether they have something to hide.

With these new developments, it can feel like Hollywood’s wildest invasion fantasies might actually be inching closer to reality. The defense bill orders the National Archives and Records Administration to compile all top-secret government records relating to the ongoing national-security puzzle of enigmatic entities witnessed in the air, the ocean and the beyond. The meta-theatrics of the government looking into whether the government knows more than the government lets on is reminiscent of one of the more meta extraterrestrial films in recent memory: Wes Anderson’s Asteroid City, a surrealist 2023 comedy set in the postwar period about a cosmic visitor crashing a junior-astronomer convention in the American desert.

“The sweeping urgency of Schumer’s message to the American people could have been ripped out of a film script.”

“Asteroid City does not exist,” the unnamed Twilight Zone–like host (a mustached Bryan Cranston) tells us—sounding very much like a lawmaker—at the movie’s start, referring to a movie called Asteroid City about a televised play called Asteroid City set in the fictional town of Asteroid City. “The characters are fictional, the text hypothetical, the events an apocryphal fabrication,” we’re assured.

Pardon the tinfoil hat on my head, but as it stands now the government’s official response continues to look like a never-ending cover-up of, well, who knows exactly what. Still, in a world where climate cataclysms know no fences, and as Hollywood finds itself in a real-life war of the words with sentient A.I. and streams of disinformation flood TikTok, it feels weirdly right that aliens are again buzzing the modern psyche, flickering in and out of our attention spans like airplane Wi-Fi service.

As it turns out, Hollywood hasn’t just been priming our imaginations with the possibility of life on distant planets. Somewhere between the world’s inaugural alien movie, Georges Méliès’s A Trip to the Moon from 1902, and the Guardians of the Galaxy franchise, a number of exceptional films seem unnervingly prescient about what an otherworldly encounter might look like.

The Day the Earth Stood Still, dir. Robert Wise, 1951

Craft

The Day the Earth Stood Still (1951)

In 1950s cinema, spaceships were envisioned in the form of airborne disco balls, fleets of intergalactic ornaments with flamboyant strobes and a cacophony of beeps and boops. But in The Day the Earth Stood Still, hushed black-and-white footage shows a single streamlined spacecraft, as pure as a beam of light, silently whipping around Earth’s skies, no louder than a gravitational wave. That silence is broken when the craft, landing on a baseball field in Washington, D.C., roars like an industrial-grade lawn mower. Civilians scatter and the Army rolls in. But the panicked reaction is less because the spaceship looks monstrously gruesome than because it looks like the future. “Holy Christmas!” a radar technician exclaims.

Remarkably, those first scenes of the spacecraft—a blurry white oval traversing the skies like a Martian mosquito—mirror footage of one of the most famous UAP cases: a cigar-shaped craft, likened to a Tic Tac, chased by two Navy F/A-18F Super Hornets off the coast of San Diego in 2004 as it’s filmed by an advanced infrared camera installed on one of the fighter planes. The object dropped from 80,000 feet to sea level in the blip of the radar and lacked any “visible means of propulsion,” according to under-oath congressional testimony by retired Cmdr. David Fravor, one of the pilots. The declassified clip has such cult status in modern ufology that mugs emblazoned with radar captures and “Tic Tac Attack!” T-shirts are sold online.

Other than Bernard Herrmann’s spooky theremin score, the best part of The Day the Earth Stood Still is the craft itself, designed by American architect Frank Lloyd Wright along with set designers Thomas Little and Claude Carpenter. They built their futuristic model out of wood, wire and plaster of Paris. Though the spaceshift references some of the architect’s modernist buildings, notably the Johnson Wax Headquarters in Racine, Wisconsin, the blueprint for the craft mostly bucked earthly aesthetics. According to Wright, the smooth surface was to resemble “an experimental substance that…acts like living tissue. If cut, the rift would appear to heal like a wound, leaving a continuous surface with no scar.”

The film’s low-key special effects only heighten the physical beauty of the unearthly object, as if it is indeed a 3D printout of the Defense Department’s typography of UAP characteristics. To create the illusion that the spaceship had no seams, the door cracks were filled with putty and painted over in chrome. When cameras filmed the sliding entryway, the putty filler ripped apart, thus making the door “seamlessly” appear. For the uninterrupted closing of the spaceship’s ramp, director Robert Wise, a longtime believer in the possibility of UFOs, who consulted with the National Guard during filming, reversed the initial shot of the opening door to reproduce the smooth transition.

Today Wright’s minimalist composition matches not just the form but the function of reported UAP. The Pentagon theorizes that UAP can accelerate instantaneously in any direction. To do this, UAP are usually round and smooth, lacking flight surfaces like wings and afterburners. Unlike a Delta Airbus, a UAP moves stealthily. Instead of sonic booms or vapor trails, emitted by aircraft breaking the sound barrier, the UAP’s “anti-gravity lift” allows it to overcome Earth’s gravitational field with no trace of propelling force. This kind of engineless acceleration is visible in the iconic closing scene of The Day the Earth Stood Still, when the craft departs Earth for outer space, achieving hypersonic velocity with only a gentle pulsating light.

“Your choice is simple: Join us and live in peace, or pursue your present course and face obliteration,” Klaatu tells Earth’s citizens during the final boarding. As the mysterious spaceman enters his vessel, he issues a command to his robot copilot that is now forever preserved (along with the film) in the Library of Congress’s National Film Registry: “Gort: Baringa!”

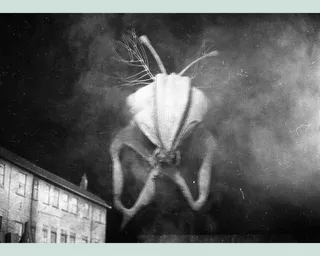

Quatermass and the Pit, dir. Roy Ward Baker, 1967

Evidence

Quatermass and the Pit (1967)

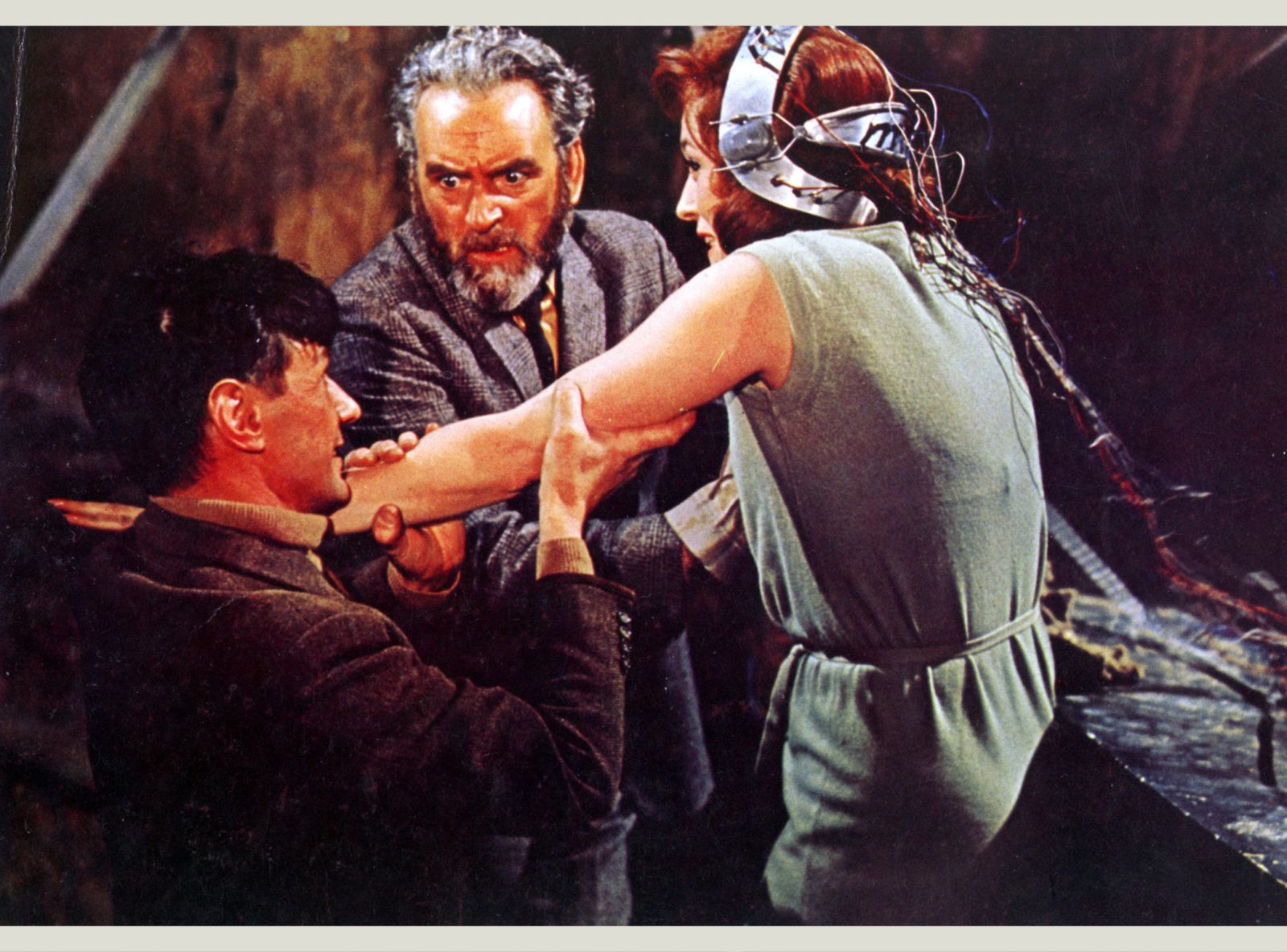

Nothing was a bigger hit on U.K. television sets in the 1950s than the Quatermass serial, a series of live broadcasts for the BBC about a fictional scientist named Professor Bernard Quatermass, who uncovers all manner of unexplainable forces. Quatermass and the Pit, the 1967 film adaptation directed by cult British filmmaker Roy Ward Baker, influenced the likes of Stephen King and served as a blueprint for The X-Files.

Quatermass and the Pit opens with a construction scene in the London Underground. Work is soon suspended after ancient skulls are discovered alongside a huge metallic object. Dr. Roney (James Donald) deduces that the bones come from “an apeman,” likely one who lived around five million years ago. Uh-oh, that time period surpasses known ancestral humans! Might there be a history of pre-human life? (Or “non-human intelligence,” as officials say nowadays.)

A military bomb-disposal unit initially mislabels the metal object as a Nazi missile. This “bomb,” too, dates back millions of years? Nothing adds up. The material, some sort of nonmetallic alloy, is resistant to drills. When teams of experts torch it with oxyacetylene, no heat is retained. Perhaps, the scientists wonder, it’s something Martian. In real time the characters grapple with just how far this twisted yarn might unspool. Could any of these unearthly hypotheses possibly be true?

In the early 2022, Stanford professor of pathology Garry Nolan shifted his attention from cancer biology to approximately 50 pounds of molten iron that, 45 years earlier, appeared to drop from the stars above Council Bluffs, Iowa. The December 1977 incident, observed by multiple people as a hovering “luminous red mass,” had already been credibly ruled out as a meteorite, satellite, aircraft or hoax.

From left: alien phenomena in the 1958-59 TV serial Quatermass and the Pit; a poster for Quatermass II

Nolan and his team found mostly iron with “isotopically ordinary” elements, albeit “atypically mixed.” Between terrestrial explanations, however, their paper (which appeared in the January 2022 issue of Progress in Aesrospace Sciences) posited the material could be wreckage from an advanced spacecraft—the first peer-reviewed study to position a UAP artifact as a bona fide possibility. “Slowly moving up the proof scale is the best way to do science,” Nolan told Stanford magazine.

Quatermass spends much of its 97-minute run time focusing on presumptions of proofiness. When Professor Quatermass (Andrew Keir) reveals the unearthed debris is likely Martian, he angers Colonel Breen (Julian Glover), since the Ministry of Defense has not sanctioned such a statement.

It’s a familiar story. At the July 2023 congressional hearing, former Air Force intelligence officer David Grusch testified that the federal government intentionally withholds public information about recovered spacecraft and “nonhuman biologics,” an echo of the film’s pre-human bones and alien alloys in Quatermass.

Like the headlines unleashed by today’s UFO whistleblowers, a press conference in the film about spacecraft origin enraptures the public. Ultimately in Quatermass, the alien allegations trigger a cataclysm of violent social unrest spurred by Martian mind control more destructive than the world has ever seen—though an outcome not entirely unforeseen.

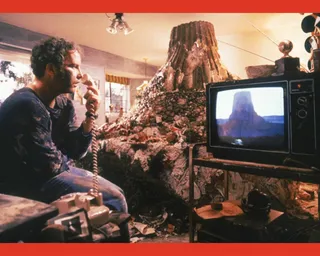

Richard Dreyfuss (and friends) in Close Encounters of the Third Kind

Obsession

Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977)

“I’m the one person who perhaps deserves a UFO sighting, and yet it hasn’t happened for me,” director Steven Spielberg tells author Laurent Bouzereau in the book Spielberg: The First Ten Years.

This backward glance arrives at a moment when Encounters, a four-part docuseries revisiting real-world sightings created by Spielberg’s own production company, is a smash hit for Netflix. Asteroid City is filled with cinematic allusions to Close Encounters of the Third Kind, and director Wes Anderson gives Spielberg “special thanks” in the closing credits.

In the nearly half-century since Close Encounters, no film has portrayed the phenomena of alien contact with as much grace and reverence as Spielberg’s 1977 drama. It’s as though you’re watching UAP in their native habitat, like sea otters frolicking in a bay off the coast of California. Once the crafts enter Earth’s atmosphere, they interfere with car engines, short-circuit electrical equipment and materialize in various shapes and sizes, occasionally coming together to merge into a single object. Like the low observability, or cloaking behavior, described by Ryan Graves, a former Navy fighter pilot who recently reported his sightings to Congress, the film’s UAP are sometimes seen by witnesses, sometimes not.

“From the behavioral science point of view,” Spielberg said in an on-set interview at the time, “I was just as interested in finding out why people looked to the skies, and want to believe, as I was in looking to the skies myself, to try to understand what’s happening up there that the Air Force and the government don’t want to tell us about.”

The movie’s title is derived from the classification of UFO encounters defined by J. Allen Hynek, an astronomer who worked on Project Blue Book, the government’s secret study of UFOs in the ’50s and ’60s. Hynek was hired as a consultant on Close Encounters and makes a brief cameo in the movie. “Even though the film is fiction, it’s based for the most part on the known facts of the UFO mystery, and it certainly catches the flavor of the phenomenon,” Hynek said. As he saw it, the then-31-year-old director “put his career on the line” by wading into murky UFO waters after his monster hit Jaws.

From left: the alien arrival in The Day the Earth Stood Still, a dinner scene in Close Encounters of the Third Kind, the theremin score from The Day the Earth Stood Still, a trailer for Quatermass and the Pit

The film’s Midwestern protagonist, Roy Neary (Richard Dreyfuss) also has everything to lose. So fixated with his encounters that he risks losing his telephone-lineman job, family, and in one memorable scene involving mashed potatoes, his mind.

Obsession fuels the film’s parallel stories. In the first thread, government researchers investigate a rash of strange reappearances of historical aircraft and ships. One of the lead scientists (played by filmmaker François Truffaut) toys with the Kodály method, an educational concept that music offers students a cultural, emotional and spiritual connection; he pairs tonal music—a universal language—with corresponding hand signals in an effort to communicate with the aliens. In the other storyline, everyday citizens have a major UFO itch to scratch, which worsens as encounters escalate from the first (seeing flashes of bright lights in the sky) to the second (the physical effect of “sunburns” from the sightings) to ultimately, in the climactic finale, the third kind (i.e., an actual meet and greet with the UFO’s occupants).

Evidence of today’s “Are we alone?” addictions includes Redditors with names like UAPDisclosure and the paranoid peanut galleries of #ufotwitter. It includes personalities like Aaron Rodgers, the New York Jets quarterback who recently divulged his own personal UFO sighting on HBO’s Hard Knocks, and Tom DeLonge of Blink-182, the director of the 2023 alien B-movie Monsters of California and founder of To the Stars, a board of former aerospace and Department of Defense officials that lobbied for declassification of the infamous “Tic Tac” video. Last year, Olivia Rodrigo told Rolling Stone, “I only look at alien-conspiracy theories.”

And there’s Spielberg himself. “I read everything on the market, including the clippings from the National Inquirer and the wire services, and even tried to get into the Blue Book archives, long before the project was declassified, to no avail,” he remarked.

The fanaticism baked into Close Encounters is sweetened by shimmers of philosophy, largely based on the galaxy brain of the now-84-year-old French astronomer and computer scientist Jacques Vallée. It’s the stuff of ufology and cinema legend that Spielberg invited Vallée, a type of Jacques Derrida–meets–Carl Sagan figure, to be a part of filming. (Truffaut’s character is an homage to the cosmic thinker.) Appearing to behave more like living organisms than galactic gadgetry, the film’s luminous, plasma-like spheres of light were inspired by Vallée’s book Challenge to Science: The UFO Enigma and designed by Douglas Trumbull, the special photographic effects supervisor on 2001: A Space Odyssey.

Vallée thought the movie’s we-are-all-stardust ending—groovy gray aliens land at Devils Tower, in Wyoming, returning missing veterans to Earth and adopting Dreyfuss’s character onto their ship—veered away from accepted theorems. To Vallée, the UAP phenomenon is more court jesters of consciousness than straight alien visitors. Spielberg, however, knew that one just sips, not swigs, from the esoteric Kool-Aid if one wants to be palatable for the ticket-buying masses. Sure enough: Close Encounters opening-weekend box office would beat out Star Wars’.

That’s not to say the movie doesn’t raise eyebrows. In one scene where military personnel prepare for the alien landing, the camera pans over shipping crates labeled “Lockheed,” “Rockwell International” and the names of other actual defense contractors. Flash forward to last July’s UAP hearing, when Congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez quizzed former military witnesses about “the interactions between defense-contractor companies and any UAP-related programs or activities.” Ocasio-Cortez was responding to a 2003 account of “a large group of Boeing contractors,” operating near California’s Vandenberg Air Force Base, who “observed a very large, 100-yard-sided red square approach the base from the ocean and hover at low altitude over one of the launch facilities.”

After reading Spielberg’s script for Close Encounters, NASA reportedly sent him a 20-page letter suggesting that releasing the film would be dangerous. For the director, the correspondence was close enough to a real encounter. “I really found my faith when I heard that the government was opposed to the film,” he said in 1978. “I knew there must be something happening.”