Two or Three Things I Do Know About Cassavetes

By Garth Risk Hallberg

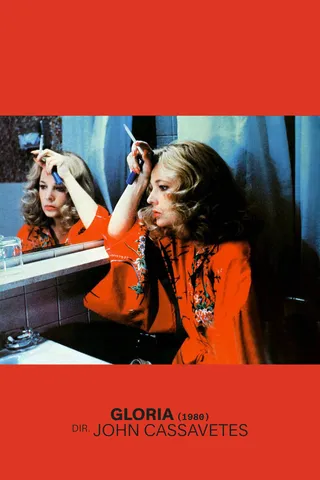

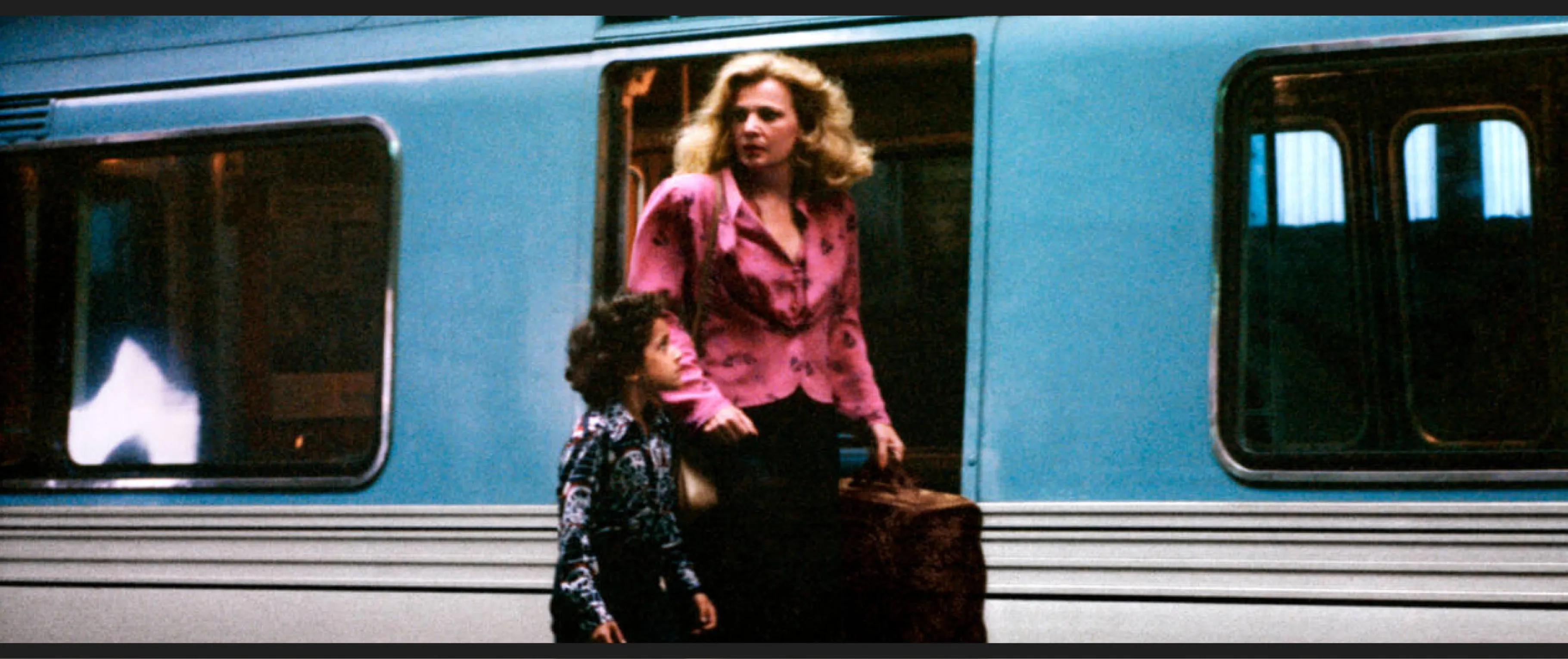

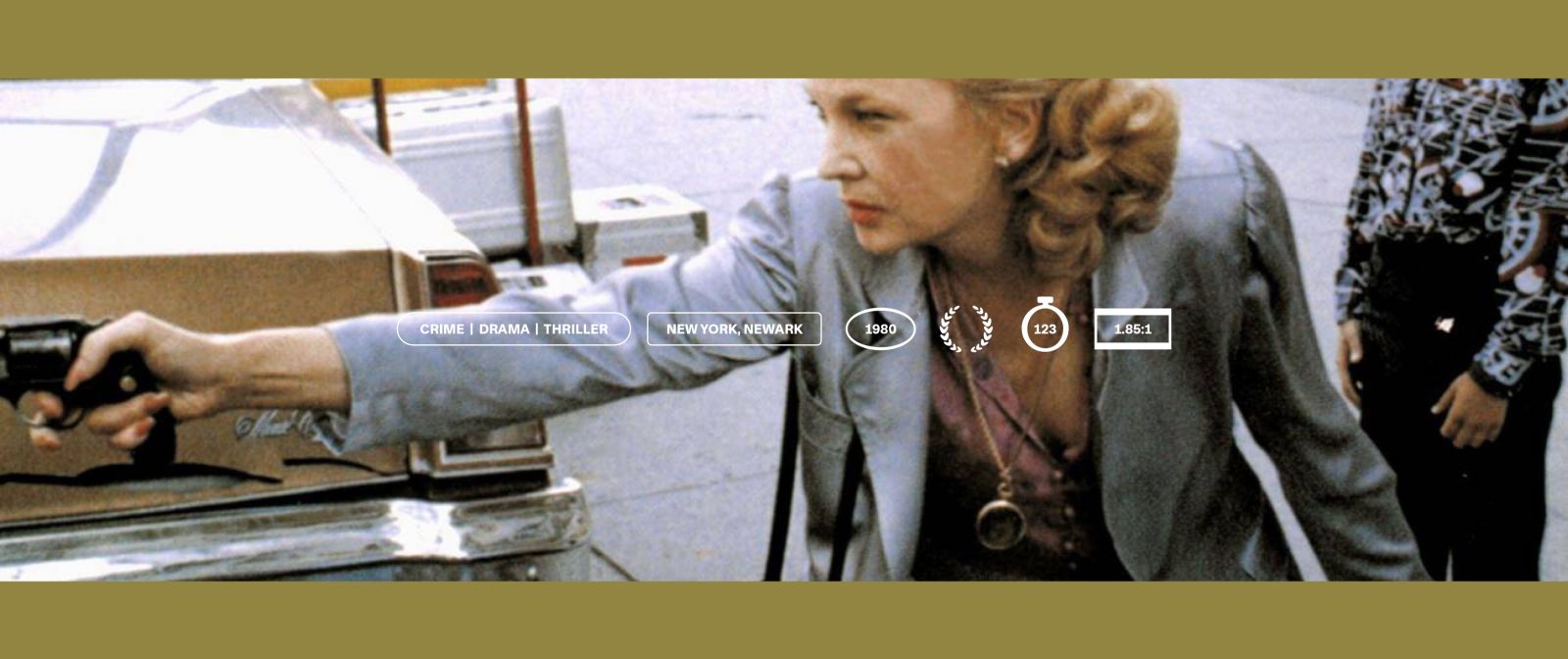

Gloria, dir. John Cassavetes, 1980

Two or Three Things I Do Know About Cassavetes

Starting with the single greatest thing in many of his films: Gena Rowlands

By Garth Risk Hallberg

August 16, 2024

The novelist Jonathan Lethem has a lovely essay called “Two or Three Things I Dunno About Cassavetes.” Despite the aw-shucks tone you hear in the title, you get to the end and you go: Yep. There are exactly two or three things Lethem doesn’t know about Cassavetes. As for the rest—biography, filmography, metatextual exegesis—he’s pretty much got it covered.

AUTHOR READS

![]()

![]()

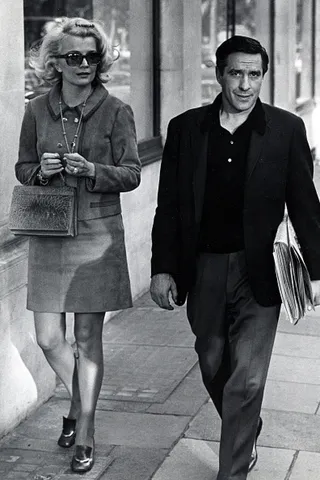

Gena Rowlands and John Cassavetes outside the Dorchester in London, 1969

I am no Jonathan Lethem, and I’m afraid that if this essay needs a title, it should be more like “Two or Three Things I Do Know About Cassavetes.” For starters, I know that I came to this director’s work late, by way of two punk bands that had more or less shaped my life. One of them, the seminal DC post-hardcore outfit Fugazi, had, in 1993, released the song “Cassavetes,” with lyrics figuring the director as a patron saint for artists of uncompromising independence: “the lights came up, my heart beating like a riot—riot…complete control for Cassavetes / If it’s not for sale you can’t buy it—buy it / Hollywood...you poor city of shame / Ask me what you’re needing / I’ll front you his name.” Then, a few years later, the feminist dance-punk group Le Tigre produced a quasi–companion piece called “What’s Yr Take on Cassavetes.” Its verse intoned the question like a mantra, while a back-and-forth chorus seemed to endorse every possible answer: “Misogynist! Genius!” “Alcoholic! Messiah!”

And so, when I finally sat down to watch Gloria, the first piece of Cassavetes’s work I’d ever seen, my receptors were already sort of primed. But only sort of, because my reaction to this film was what it always is in the face of the art that speaks to me deeply: a total, visceral torch put to my preconceptions.

This was some time in the mid-aughts, and I was researching a book about New York that would become my first novel. I was looking for mise-en-scène from the city’s turbulent ’70s, and Gloria has mise-en-scène for days. I love, for example, that the skimming mob accountant still lives in a hellhole apartment building in the Bronx; it’s such a testament to the power of rent control. But the movie also finds improbable beauty in that building, as it does in everything else: the blue crown of a gas stove’s burner, the rhyme of a hamburger wrapper and a summer dress, the updraft off the Harlem River…and everywhere, the light, the incredible New York light. All this while the movie is chiefly about a woman (Gena Rowlands) who is trying to protect a little boy from a gang of hit men who already took out the rest of his family.

I’m tempted to call Gloria’s openness to beauty democratic rather than cinematic, and it’s the first of a few discrete elements that emerge for me when I try to subject the hot insanity of this film to the cool scalpel of rational analysis. That beauty arises, on one hand, from expressions of culture. There are the watercolor paintings by Romare Bearden used during the opening credits, Rowlands’s wardrobe by Emanuel Ungaro, the jazz-infused soundtrack by the great Bill Conti. (Really, all the best people are here.) And at a more mundane level, there’s the SOS of our heroine’s steps as she flees the bad guys (backward, then in high heels), the sweep of brick architecture snapping closed like a trap, plus a thousand other human moments caught as if on the wing: the multiethnic huddle of neighbors in a hall, the alarm of fellow passengers as a bus lurches to a stop, the apparent propensity of mob bosses to lunch at Penn Station.… And yet there is also, insistently, the beauty of the natural world: the verdure of a graveyard on a summer day and the breeze ruffling the streets. At times you can feel Gloria trying to annihilate the distinction between artifice and naturalness altogether.

“Gena-slash-Gloria has become the self that touches all edges: a force of nature, a pistol-packing mama, an avatar of the cityscape…”

A similar annihilation, or affirmation, is the way it blends auteurist eccentricity with genre as if it’s the most natural combo in the world. Some of Cassavetes’s stuff is film, but this is a movie that knows how to be a movie, complete with chase scenes and “don’t answer that telephone” moments. Indeed, the plot is a string of such moments, staged with utter physical commitment. Which serves as a reminder: Art can be—and sometimes should be—demanding and fun at the same time.

The third, and related, blurring is the mash-up of realism and expressionism that makes the whole Cassavetes catalog in general so galvanizing. There’s something gratuitously real about the tipped-over shopping cart on a Bronx street corner at the beginning of the film. It’s a detail worthy of Tolstoy. And then two minutes later, we’re in a Kafka story, with a family having an argument that is incoherent on the level of content—we haven’t even been introduced!—yet formally the archetype of all family arguments.

Some of this psychogeography is drawn out by the let’s-say-idiosyncratic performance of John Adames as the 6-year-old co-lead. He tied with Sir Laurence Olivier in 1980 for a Razzie Award for Worst Supporting Actor, but I think his turn beautifully serves a purpose here, as in the Japanese aesthetic concept of wabi-sabi—the flaw that perfects the perfection. Little Phil is less a character than a pathology, and every time he goes into one of his fugue states (“I am the man! I am the man! Do you hear me?”), you feel like you’re simultaneously in the historical reality of New York and in the fathomless dreamscape of the auteur’s head. In fact, when I see little John Adames packed into his gorgeous leisurewear, I can’t help thinking he was David Lynch’s unconscious inspiration for the dwarf in Twin Peaks. “I’ve got good news. That gum you like is going to come back in style.”

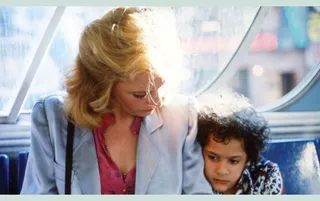

From left: Gena Rowlands and John Adames in Gloria; Gena Rowlands in Gloria

But then counterbalancing Adames is the single greatest thing in the film, and in many Cassavetes films: Gena fucking Rowlands. Every move, every inflection, every thought crossing her face, every thoughtless gesture, grounds this fantasia, this expressionist gangster flick, in stone conviction. In this film she is, to me, New York incarnate—smart, annoyed, impatient, improvisatory, tolerant, braced for the unreal and competent as all get-out. And along with the city, she’s the most beautiful thing in the picture.

Consider two early moments bookended so seamlessly, so organically, that you almost don’t notice the echo. In one, Gloria is in desperate need of a cab, but they keep passing her by. Now personally, I can’t imagine ever not stopping for Gena Rowlands. She has the quality shared by only the most rarefied of movie stars—you’re content just to watch her be. But then you remember just how far uptown we are, and you see Gloria lugging her carpetbag, a vulnerable woman up against the brutality of the city, and you think, as so often when watching Cassavetes: Well, that’s just how life is.

And then four minutes later (spoiler alert), Gloria has shot up a car full of mobsters in plain view of the kid, and suddenly she is Pacino in The Godfather Part III, pulled back into “the life” she wants to leave. Or she is Batman casting off the pretense of being merely Bruce Wayne. Or she is Amanda Plummer in the opening of Pulp Fiction, jumping out from a diner booth to reveal she’s packing heat. But whereas Plummer’s line reading, in perfervid L.A., is so deliciously unhinged that it’s become an in-joke between me and my wife—“I’ll execute every motherfucking last one of you!”—Rowlands’s reaction is to smooth her hair and yell “Taxi!” as if to say, “Have I made myself clear?” On this most cabless of streets, a cab immediately pulls up. Gena-slash-Gloria has become the self that touches all edges: a force of nature, a pistol-packing mama, an avatar of the cityscape that will, for the next 90 minutes, keep her and little Phil one step ahead of the gun.

“In one [scene], Gloria is in desperate need of a cab, but they keep passing her by. Now personally, I can’t imagine ever not stopping for Gena Rowlands.”

Gena Rowlands and John Adames in Gloria

To watch Rowlands as attentively as Cassavetes does over the course of these twists and turns is to somehow resolve the misogynist/genius dialectic you hear in the Le Tigre song. I don’t mean simply that the camera loves her, though it does. I mean that, try as she might for steely independence, Gloria’s full character emerges only in relationship. Rewatching the film recently, having just finished a second novel about a father and a child who go on the lam, I was primed to read her 90-minute flight with little Phil as a parable of parenthood. Instead, it is clear that their story is a facacta romance. This is made almost explicit in the scene where Phil, lolling in his underwear, plays with Gloria’s hair and asks if she loves him. We flash back to his comic insistence, earlier, that “I am the man,” and see it differently. Rather than an indictment of Phil’s childish misapprehension—his drag-like mimicry-cum-deconstruction of what he believes a man to be (yelly, emotionally incontinent)—we now read it dead straight. Phil is the man, at least as Cassavetes understands the term: i.e., an impulsive and intermittently aphasic pip-squeak in thrall to, and unable to read, the sovereign mystery of the feminine. Misogyny, as it so often does, emerges as a form of misandry: a reversion to type, an inability to imagine a man who might be worthy of womanhood. We see instead a three-foot-six double for Cassavetes himself, dwarfed by the majesty of his wife and muse and go-to star and partner in crime: “Do you love me?”

I do—to death. I am aware that Gloria is no Faces, no Love Streams, not one of the five or six high-canonical Cassavetes productions. But because it was my first non-punk-rock exposure to this great artist (or rather, these great artists, John and Gena), it remains number one in my heart. I’ll add only that in the fall of 2013, the week before the manuscript of City on Fire went out to publishers, the novel was still missing a title. I’d spent six years writing 900 pages and yet somehow neglected to give it a name. Someone in the literary agency was pushing hard for, you guessed it…Gloria. But I shot that down. There’s the Cassavetes movie. Have you not seen the Cassavetes movie? I had written something that was nakedly unafraid to be under the influence of the masterpieces I worshipped—Bleak House, Middlemarch, Underworld…but you don’t want to get in the ring with Gena Rowlands.