Lucrecia Martel’s Cinema of Doubt

By Kaleem Aftab

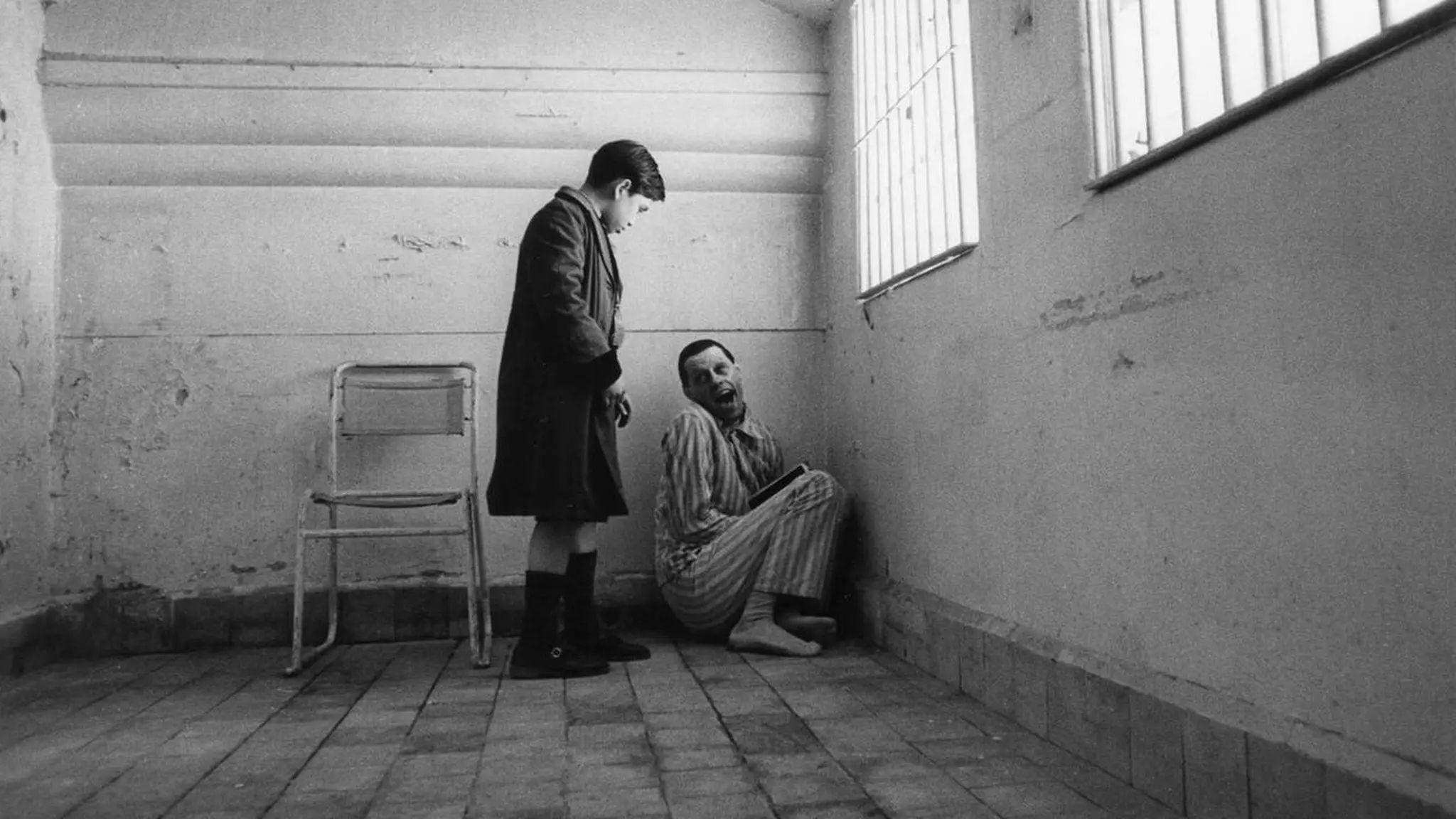

The Headless Woman, dir. Lucrecia Martel, 2008

Where Is My Mind?

Lucrecia Martel’s politically

charged cinema of doubt

By Kaleem Aftab

September 1, 2023

The Headless Woman, acclaimed Argentine director Lucrecia Martel’s masterful, unnerving treatise on memory and truth, starts innocently enough. Boys climb billboards and play with their dog by a Salta roadside. We cut to middle-aged Verónica (María Onetto), or “Vero,” who works in a dental clinic, leaving an event where her middle-class friends chatter and extol her new blond hairstyle. Distracted by her cell phone, she hits something on the road. When she pauses and looks in her rearview mirror, she sees a motionless hound. The facts seem established—except for a mysterious change on the driver’s door window: Condensation markings become more accentuated and then seem to mysteriously change shape, looking like something between a paw and handprint. This otherworldly directorial flourish creates enough uncertainty and confusion that when Vero eventually convinces herself that, despite seeing a dog carcass on the road, she has in actuality killed a child, it slowly becomes plausible to us viewers as well.

In The Headless Woman, Lucrecia Martel interrogates our relationship with reality

Two alternate realities play out in a scene directed and edited as if part of one continuous timeline. It’s a version of the multiverse as far from Marvel as is imaginable, more comparable to David Lynch’s Mulholland Drive, but without gimmicks to explain why contradictory events seem to happen simultaneously. In Martel’s multiverse, fact and fiction are like strands of spaghetti, twisting and turning in intersecting and sometimes broken circles. Each of her four feature films over the past 20 years defies tidy categorization—emotional interactions transcend plot, and an aesthetic approach that at first glance seems like neorealism is more otherworldly. The visual and aural clues are sometimes hard to notice or decipher, forcing the viewer to turn detective, with important details seen fleetingly at the frame’s edge, or people whispering secrets that they want to hide, even from the viewer. The camera takes in the action in an inquisitive mood, making small directional movements like someone turning their head, following the characters but unable to capture everything from its vantage point. The controlled aesthetics of Hollywood studios are rejected and chaos reigns.

The clue to the bedlam is in the title. The Headless Woman references the mythical horseman who loses his head and spends the rest of time searching for it. It’s a sad but apt metaphor for how many people spend their lives looking for peace of mind. In the cinema of Martel, characters metaphorically lose their heads all the time, and none more so than Vero. We see her go from the relief of being told that no child has been found on the day of the crash, to the horror one week later of seeing firemen draining the canal after a dead body has been found. The whole time, Vero and the audience have been disoriented. After the crash, seemingly in shock, she has a fling with a relation’s husband (Daniel Genoud), and shortly after confides her fear that she killed a boy to her husband, Marcos. Meanwhile, her well-to-do and predominantly light-skinned friends are more worried about the possible contamination of a swimming pool than the death of a young dark-skinned worker in their community. Life goes on, but for Vero what happened on the roadside will soon come to haunt her.

Over two decades Martel has become a cinephile darling (along with her four films, she’s made several documentaries and a smattering of shorts), championed by film festival programmers and art-house audiences. For her many fans, it’s incongruous that the director isn’t a household name. Her films are visually, aurally and structurally daring, making the personal political to confront power structures. Her international breakthrough came in 2001 with her feature film debut La Ciénaga, which won prizes in Sundance and Berlin. The drama hinges on the lives and dysfunctional marriages of two female cousins, one richer than the other, sharing houses for the summer with their frustrating husbands, disinterested children and forlorn servants. Her sophomore effort, The Holy Girl (2004), is a tale of sexual awakening in and around Catholic schoolgirls that doesn’t sermonize about inappropriate behavior. Then, in 2008, came The Headless Woman, to complete the so-called Salta trilogy, three films about perturbed female characters set in the area where Martel grew up in northwest Argentina. Even when Martel eventually moved away from Salta and women protagonists, her film Zama (2017), a loose adaptation of Antonio Di Benedetto’s novel set in the late-18th century, still delivered a collection of scenes and incidents highlighting the failings and absurdities of patriarchal power elites.

From left: La Ciénaga (2001), Zama (2017), The Holy Girl (2004), dir. Lucrecia Martel; Pink Floyd: The Wall, dir. Alan Parker, 1982

The unusual way Martel’s stories unfold are rebukes to the reign of the three-act structure. The emphasis is on character, with scenes that often have no clear start or finish and hang together like splintered glass, more like observational documentaries, in which spending time with the subjects leads us to understanding a greater truth. It made sense that Visions du Réel (the renowned international documentary festival held every April in Nyon, Switzerland) celebrated Martel’s oeuvre this year with screenings of her films and a master class exploring Martel’s “body of work and her relationship with reality.” When we met at a hotel bar during the festival, the 56-year-old Martel was sporting her trademark cat-eye spectacles—an apt statement for an artist who interrogates how we see things.

While her filmmaking traffics in subtlety, in person Martel is prone to big pronouncements. “I truly believe that it’s not humans’ ability to reason that distinguishes us, but our ability to create a parallel reality, to distort what is around us and surrounds us,” she tells me. In The Headless Woman, Martel uses Vero’s confusion to illustrate this existential provocation. When Vero realizes someone has died—a boy from a family that she barely knows—she begins her own investigation. Weird things happen. She returns to a clinic where she had an X-ray after the crash, only to discover that there was no record of her ever having been there. Did she imagine this as well? Or is it, as her intuition tells her, that her friends and family have covered up her crime? Martel’s storytelling, clever or maddening depending on your point of view, doesn’t seem to want to give many straight answers. The challenge for her friends in the film—and for the audience—is to piece together the clues and come up with our own conclusion, in effect creating our own reality.

By structuring The Headless Woman like a puzzle, Martel shows how what people want to believe becomes “truth,” especially if they are members of the power elite. In Nyon, sipping morning tea, she gives me a concrete cultural example to illustrate her point: “The average person in Latin America works 12 to 16 hours daily, whether formal or informal. However, the perception in Latin America is that the lower-middle class and working class are lazy. The middle class then make policies based on this misconception.” Consequently, when Vero and her friends insist that she killed a dog, it’s immediately believed, and when another truth emerges it serves as a parable on how the rich are able to get away with mistakes, even manslaughter.

In Martel’s films one has to pay particular attention to the auteur’s sleight of hand and aural indications. It would be easy to read the film as being about a woman in shock, unable to make rational decisions or distinguish fact from fiction—a madwoman. Martel recalls with some bewilderment the reactions to the film in Cannes: “When we premiered The Headless Woman, some French journalists asked me, ‘What type of mental illness does this woman have?’ None. She had no condition, no mental illness.”

“Martel exploits this

unconscious bias, or flat-out

misogyny, to investigate how men control the story

of women.”

But Martel is definitely poking at these societal assumptions. She manages to dupe the audience into thinking Vero is crazy by using the stereotype of the unhinged woman to her own advantage. This is reinforced by Josefina’s claim that everyone in the family eventually goes nuts. Vero’s sin, and what leads us to question her, is that she isn’t confident, and to not be certain has somehow become a sign of weakness, especially in women. Martel exploits this unconscious bias, or flat-out misogyny, to investigate how men control the story of women—in the film, Vero’s husband and brother don’t ask her permission before acting on what they think is best for her—and how being able to control the narrative is power. She realizes that it won’t feel natural or comfortable for us to accept Vero’s decision that she killed the boy, so the film challenges us to accept that this seemingly unreliable female narrator is the only trustworthy voice. The subtle way she deconstructs gender is what makes Martel such a great feminist filmmaker.

Perhaps it’s no surprise that Martel’s films tackle veracity and even the concept of logic, considering that her formative years coincided with the Argentine dictatorship and the Dirty War period, when many who questioned the government went “missing” and were presumed dead. During this era, the truth became dangerous, something best avoided. “I think the only way for this phenomenon to happen—that you don't see what’s inconvenient to see or hear—is to doubt permanently,” Martel argues. And that feeling of doubt is what connects all of her characters to the elliptical structure of her films, where nothing is definitive or obvious. To find answers one has to look beyond the surface and not accept what we are told—just like Vero does.

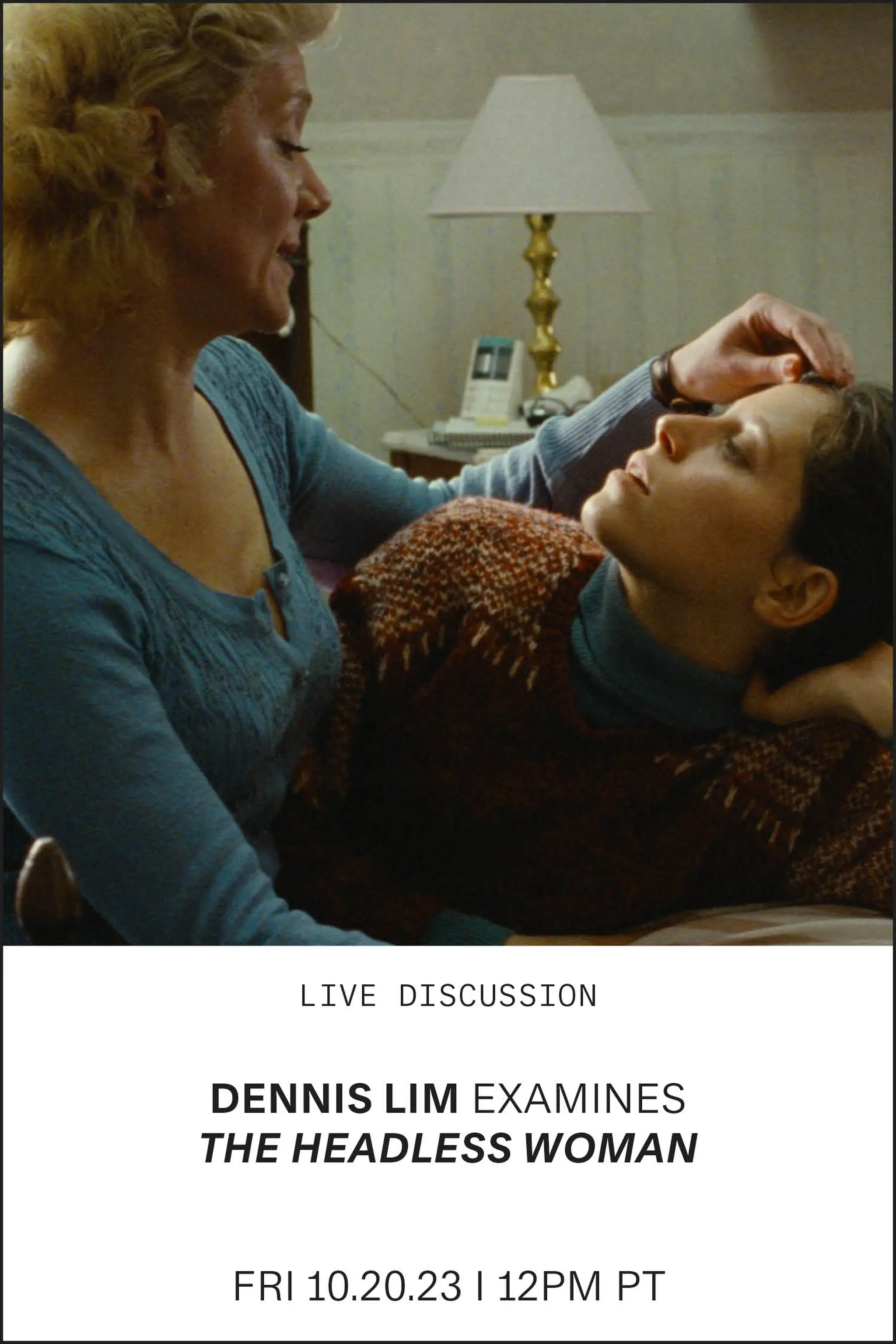

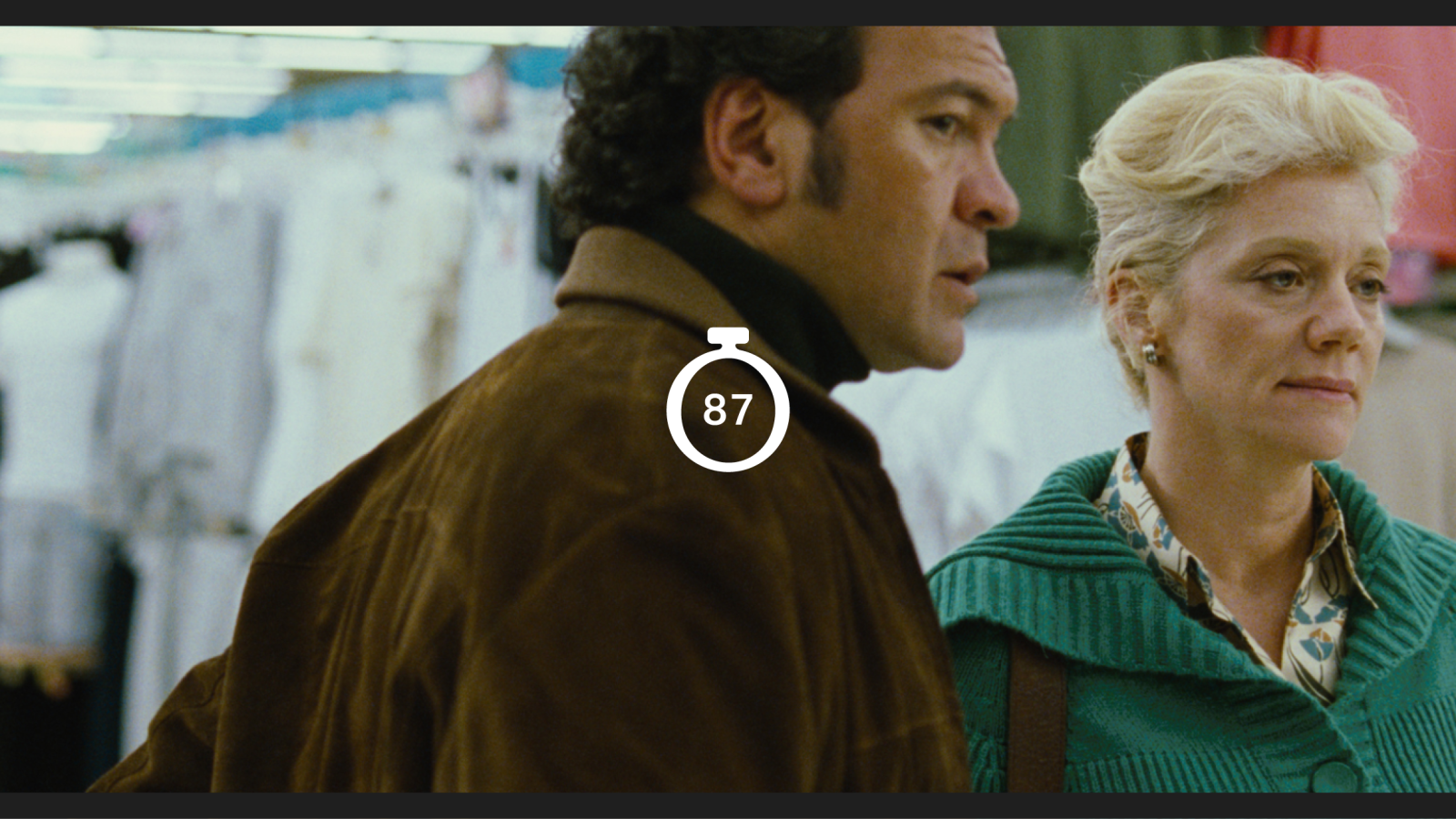

César Bordón and María Onetto in The Headless Woman

In fact, Martel gives little credence to what is said, preferring instead to focus on tone. One of her films’ most unusual features is that dialogue is often muffled, making it impossible to understand the words spoken. Instead, we hear the sounds of conversation, whether loud cacophony or whisper, which relays the mood of the characters speaking and prompts us to sense what is happening. “Reasoning can be a hindering factor to understanding something,” Martel explains. Hence, Vero intuits that she killed the boy and operates from that feeling. Curiously, Martel starts working on sound before writing the script for her films. “Thinking from and about sound generates a method of approximation and allows me to avoid some silliness from my own education,” she says.

The director attended the National School of Film Experimentation and Production (ENERC) in Buenos Aires in 1983, but a country-wide economic crisis forced its closure before she could complete the first year. This may have been a blessing in disguise, as it forced Martel to teach herself. Part of her process involved watching movies repeatedly, studying the editing, shots and angles, and one film in particular arguably led to her inimitable style of cinema: Alan Parker’s 1982 musical drama Pink Floyd: The Wall. As with Parker’s musical, Martel uses sound to drive storytelling. “For me, [sound] is essential to understand what universe the spectator will be submerged in. It gives me an idea of what I want for the movie,” she says.

When I ask Martel if she believes humans can speak truthfully, her response is satisfyingly enigmatic: “I think that every time humans tell the truth, speak the truth, is when they are furthest away from what they want to say.” Questioning what people are saying in The Headless Woman leads us to conclude that the only person who is not an unreliable narrator is Vero. We witness the world as she does, and in a confusing world she has doubts.