Antonio Lopez, Resurrected

By Christopher Bollen

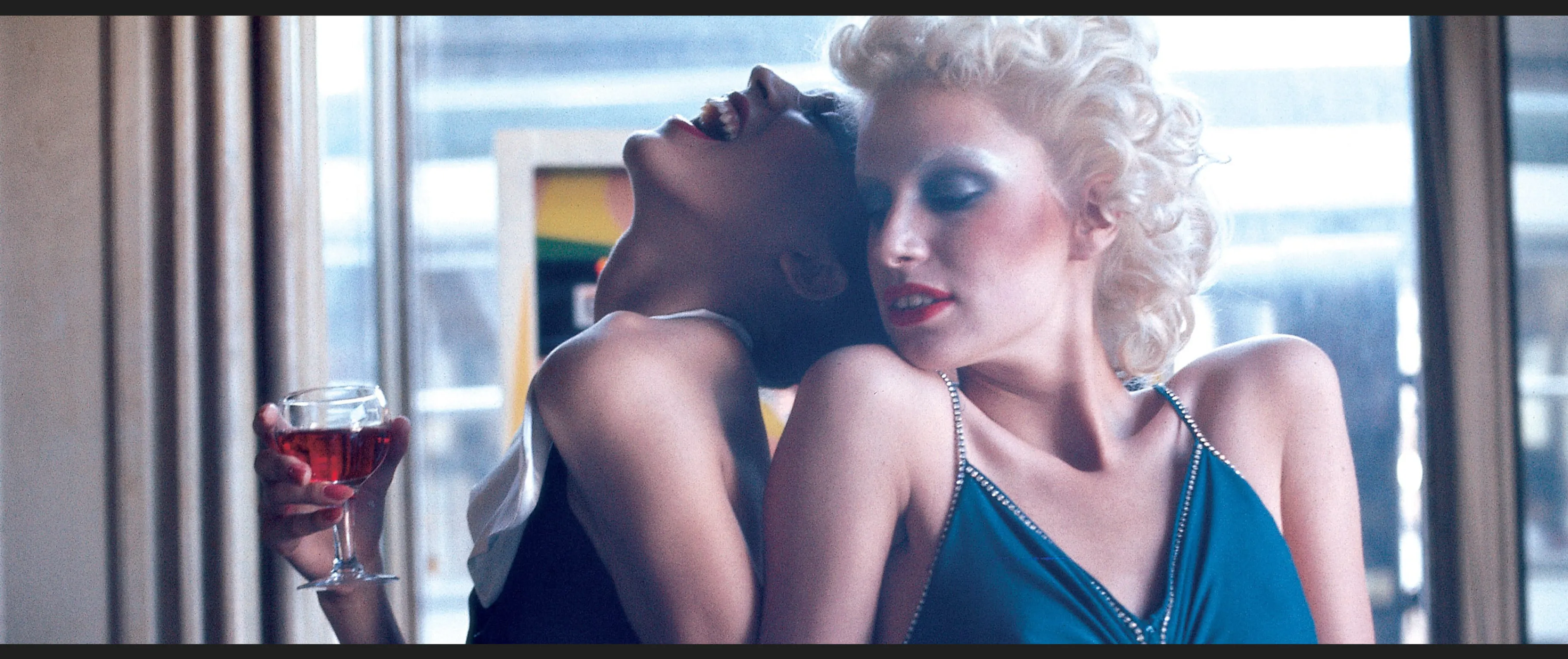

Antonio Lopez 1970: Sex Fashion & Disco, dir. James Crump, 2017

Antonio Lopez, Resurrected

By Christopher Bollen

James Crump's vital fashion documentary brings the forgotten genius of an industry powerhouse back into the limelight

September 6, 2024

Was the 1970s the most glamorous and unbridled era for art and fashion? Judging by the bold-faced names flitting between museum openings and fashion shows, between New York’s Max’s Kansas City and the dance floor of Paris’s Le Sept, the answer is a whole-hearted yes. Yet for all the attention given to the decade’s superstars like Andy Warhol, Karl Lagerfeld and Yves Saint Laurent, there are key artists and innovators whose critical contributions to the radical bohemianism of the period have sadly been forgotten. That cultural neglect is one of the reason’s director James Crump’s 2017 documentary Antonio Lopez 1970: Sex Fashion & Disco proves such essential viewing. Not only is the documentary a visual feast for fans of the Warholian avant-garde and louche Parisian glamour of the early 1970s, it also restored the reputation of one of the most prominent, freewheeling creative dynamos of the time.

Antonio Lopez was by trade a fashion illustrator for brands including Chloé and magazines like Vogue and Interview. But he was also an intuitive curator—he launched the modeling careers of Pat Cleveland, Jerry Hall and Jessica Lange, among others—and a seductive decadent whose gift lay in capturing the energy and fluidity of the era, whether on paper, in photography or simply in the social milieu he helped define. For his film, Crump mined Lopez’s abundant archive, filling the screen with the late artist’s trove of drawings, sketches, Polaroids and unseen film footage, bringing to life Lopez’s late nights working in his studio on the top of Carnegie Hall and even later nights dancing at nightclubs from Studio 54 all the way to the basement dives of Paris. Crump also wove together interviews with friends and collaborators to capture the highs and lows of Lopez’s career, from his close relationship to his art-director partner Juan Ramos to his addictions, lovers, cutting-edge fashion career and ultimately his tragic death brought on by AIDS at age 44. But the documentary’s main tone is one of celebration, and Crump’s attention to the joyous mood extended to the soundtrack: He chose the music that comprised Lopez’s personal record collection, including Donna Summer, Mavin Gaye and Curtis Mayfield.

Crump had already directed two art documentaries by the time he turned his attention to Lopez and the 1970s jet-set café society of models, designers, editors and hangers-on—the first on Robert Mapplethorpe and his lover and supporter Sam Wagstaff (Black White + Gray, 2007) and the other on 1970s Land artists such as Robert Smithson and Walter De Maria (Troublemakers, 2015). Crump spoke with Galerie about a childhood fascination with Lopez’s orbit, the challenges of resurrecting a lost era, and the highly competitive sport of fashion.

James, you had previously made films about heavyweight visual artists. I know we both agree that Antonio Lopez is a serious artist in his own right, but I’m curious what motivated you to move into documenting the world of fashion.

Well, Chris, I agree with you. There’s a lot more attention paid to Antonio’s work than there was before. But I personally came to Antonio really early on as a teenager. I became interested in high school through his work in Interview magazine, which I read religiously. In that context, the stories and world he inhabited seemed so exciting to me. Then, over the years, I learned more and more about him and was always paying attention whenever his work was published or exhibited. Fast-forward to around 1997 when I met Paul Caranicas, who was Juan Ramos’s lover, and he was the manager of the estate after Juan had passed away. We became friends, and he understood my interest in Antonio. In fact, Paul said, “You were one of the first people who knocked on the door. Later on, many people have knocked on the door, but you were the first.” He really gave me carte blanche. I was living in Santa Fe at the time, and I would go to New York to get lost in the archive. I went through thousands of drawings and Instamatics. For several years, I was just looking at the material, getting really familiar with it and just being literally titillated and looking back at a period of time that I just wished I could have been part of. Then, when I met my partner, Ronnie Sassoon, she really urged me to move forward on this particular project. The documentary was my way of entering into a realm that I wasn’t born early enough to take part in.

So it was essential for you to invoke the period of the late ’60s and ’70s.

I really wanted to make an immersive film that was also a bit of a time capsule. I wanted to transport the viewer back to this magical period when everything seemed possible, that was so open and free. And it was a time not too many years before the dark cloud of AIDS started rolling into Manhattan and other cities around the world.

Because of the staggering death toll from AIDS in the ’80s and ’90s—particularly in the fashion and art communities—it’s a miracle you had as many interviewees as you did in the film to reflect on Antonio and his bubble of bohemia.

We were fortunate. I never want to have too many talking heads. I don’t like many subjects in a documentary because it’s hard to manage, first of all. And secondly, most of the time people are saying much the same thing. I was looking for contrasts, for different stories and receptions to Antonio’s life and career. Some of the key players were there—Pat Cleveland, Jane Forth, Donna Jordan, Jessica Lange. Corey Tippin was so important. And Bob Colacello and Michael Chow. And unfortunately, there are people who we would’ve loved to have spoken with for the film, but they have sadly perished.

From a visual aspect, it must have been an even richer gold mine of material—to delve into fashion photography, film and illustration—than any of the art documentaries. The Warhol-Lagerfeld nexus of the 1970s is an embarrassment of riches.

The Antonio archive is so vast, but we tried very hard to stay within the time frame of 1968 to 1973. But Antonio was first and foremost a stylist. He was doing campaigns for fashion designers, and he actually created some collections himself. And I think because of his relationship with Andy Warhol, their friendship and their rivalry, and their mutual support of each other, I think he was always trying to go outside of just one field or practice. But for me, personally, fashion is a sport, just like it was for Antonio and for Juan. And visually, first and foremost, I wanted the film to be beautiful.

Warhol was obviously long dead when you made this doc. But Lagerfeld wasn’t. How did you navigate him as a character when he wasn’t participating in the film?

There were, of course, people who chose not to participate and one of them was Karl Lagerfeld. Karl was someone I met 25 years ago and had spent some time with. I really reached out to him and tried to persuade him to be involved. But he had a lot going on. I think it was a difficult story for him. It was a difficult period to retrace in his life. But I think in the end, it all worked out well, because Karl is represented beautifully in the movie through film archival footage. You see him in that particular moment in the 1970s, after he’d established himself at Chloé, all buffed out and butch, and it’s a special moment in his career. When you see him in that light, again, it takes you back in a transportive way. It might have been too jarring to do an on-camera interview today.

Jessica Lange and Bill Cunningham reminisce about 1970s New York in Antonio Lopez: Sex Fashion & Disco

“I wanted to transport the viewer back to this magical period when everything seemed possible, that was so open and free.”

I met him a few times too. He struck me as very similar to Warhol in that idea of never looking back. Let others tell the stories. Don’t give too much of yourself away. Maybe I’m stuck on Lagerfeld because there has been so much renewed interest in his life with that recent limited series [Becoming Lagerfeld] and with Chanel changing hands. But I have to mention the deep emotional blow at the end of your documentary, when Bill Cunningham talks about how Karl wouldn’t give them money when Antonio was sick and he really needed it for his health and survival. It’s a devastating moment, and Bill is reduced to tears. Bill is rendered beautifully in the doc. But on a filmmaking level, when you got that tragic reaction on camera, did you know you had a little piece of cinematic gold?

Bill was reticent. He wasn’t someone who talked a lot about the past or about himself. He’s a very, very quiet, almost self-effacing kind of person. Gandhi-like. Very modest. So when he came to the interview, I think he was very ready to share these stories that he’d kept to himself for many, many years. I think Bill was also cognizant of the fact that he wasn’t going to be around much longer. He was suffering physically. His health was declining. And he came to share. It was a remarkable moment for us, for Ronnie and myself, producing this film. It was so emotional and I felt it was a very key interview, and Bill had no reason to fabricate. He was not given to exaggeration. And as you can see in the film, it was very painful for him to revisit the past like that. At the end of the day of shooting, he seemed very pleased, and he was worn out. He had given it his all, and we had given it our all. We had to stop the cameras two or three times because we were all bawling.

It occurred to me while rewatching the documentary that one of the magical parts of interviewing all of these fascinating characters is that you almost have mini-documentaries on these subjects buried inside the main one. Do you interview someone on camera and think, I should use this for a separate project?

When the Troublemakers film was released, we had a tremendous amount of archival footage, and I think it was the artist Liam Gillick who said to me, “James, you could do a six-part series on this.” But I’m like other artists in that once you’ve got your project completed, you’re looking for the next one. You’re off to something else intellectually already.

What documentaries have inspired you as a filmmaker?

A film I return to a lot is Senna, about the Formula One driver who perished in a crash. It’s by Asif Kapadia and it’s a remarkable film because he relied entirely on archival footage, no talking heads. There might be maybe one or two max, but it’s an incredible art piece he produced with that film. Werner Herzog is someone I’ve paid a lot of attention to over the years. He’s one of my heroes in a lot of regards. I’m interested in hardcore filmmakers like that who are also not afraid to cross over the so-called boundaries of narrative cinema.

Portraits of Antonio Lopez in Antonio Lopez 1970: Sex Fashion & Disco

Are there any fashion documentaries you’ve admired?

One that comes to mind is Frédéric Tcheng’s Dior and I [2014]. A feature narrative fashion film that really stuck out to me is Bertrand Bonello’s Saint Laurent [2014]. It captures the spirit of Paris in that crossover period I was trying to cover in the Antonio film.

Before you got into filmmaking, you had a very successful career in museums and curation. How did you make the crossover into filmmaking?

I had done a lot of research on Robert Mapplethorpe and Sam Wagstaff, and I’d published two books on Robert’s work. I started thinking about the story of those two guys together. They shared the same birth date. They were such players in their moment in New York City. At the time, I was like, “How does one make a documentary film?” I wanted to make film, but I didn’t go to film school. I went to graduate school to study art history. I was accepted to one of the producer laboratories at Sundance in Utah, and I was able to go on a crash course for maybe five or six days with all these professionals from various aspects of the filmmaking business. And that was the impetus to basically launch off and to start shooting. It took about four or five years to produce that first film. It was a learning process, really seat-of-the-pants learning. So that’s, in a nutshell, how I got into it.

Once film got in your blood you couldn’t stop.

I spent all my time just producing this film about Sam and Robert, shooting subjects whenever I could get the opportunity and working with very little resources. I shot it by maxing out credit cards and using my savings to make that first film. It was a labor of love.