Construction Sight: Judy Becker

By Robert Bound

The Brutalist, dir. Brady Corbet, 2024

Construction Sight

Robert bound

The Brutalist production designer Judy Becker renders an architect’s grand vision on a spectacularly small scale

February 21, 2025

Production designer Judy Becker has conjured startlingly diverse cinematic worlds—from the sleazy 1970s style of David O. Russell’s American Hustle (which earned her an Oscar nomination in 2014) and the cowboy Americana of Ang Lee’s Brokeback Mountain (2005) to the saturated palettes of Lynne Ramsay’s We Need to Talk About Kevin (2011) and the mid-century interiors of Todd Haynes’s Carol (2015). Overall, Becker professes to be wary of design for design’s sake and notes that her film work is always in service of the story. “I want it to be part of the filmmaking,” she says.

For her most recent project, Brady Corbet’s feverish 2024 epic The Brutalist (for which Becker has racked up another Oscar nomination), she stepped into a story set in the post-Holocaust era, balancing elements of history, nationality, tragedy, reconstruction and ambition. Written by Corbet and his professional and life partner, Mona Fastvold, The Brutalist centers on the Bauhaus-trained Jewish Hungarian architect László Tóth (Adrien Brody), freshly arrived in the U.S. from Europe’s Second World War trauma, and his bluff yet monstrous industrialist benefactor, Harrison Lee Van Buren Sr. (Guy Pearce). While László, a melancholy but resolute genius who is also a heroin addict, awaits the arrival of his wife, Erzsébet (Felicity Jones), his patron commissions him to construct the Van Buren Institute, a supposed memorial to his late mother but clearly also a monolithic folly that will challenge both men’s reason, vanity and sanity. Van Buren wants a shrine to his own success, minted in modernism with a strong Christian dimension; László accepts but instead designs a factory-like slab of brutalism, a cross between a devilishly avant-garde cathedral and a coal-fired power station.

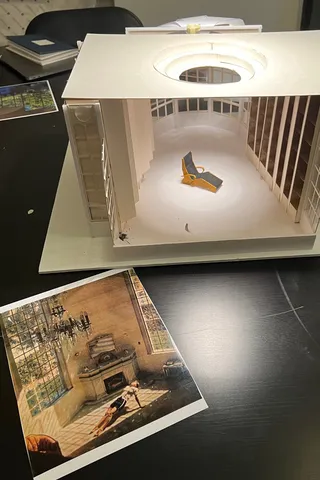

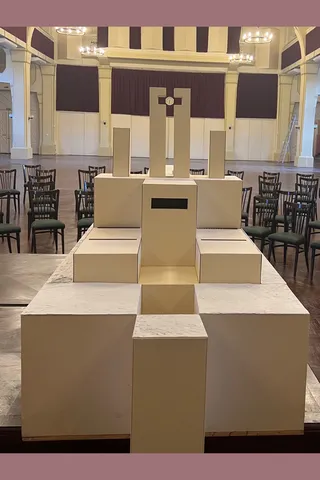

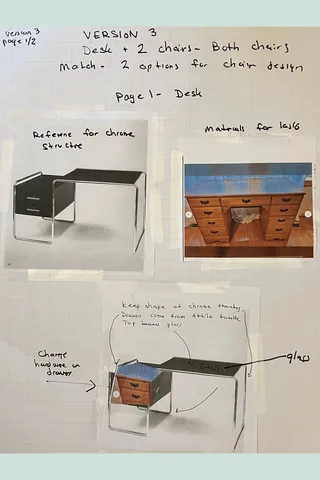

In production these grand plans were rendered in miniature—literally. After meeting with Corbet, Becker decided to create an elaborate scale model to envision the modernist, brutalist structure. A larger version treated with concrete is what the audience sees onscreen, but much of the viewer’s idea of the building is shaped by this model, which László presents to the people whose Pennsylvania town the Institute will loom over (the film was actually shot in the countryside near Budapest). Model-making became vital for a production with a notably tight budget of $10 million—if you can’t build an entire Institute, build a portion of it and be clever with the cinematography, deftly shot by Lol Crowley in dizzying angles that echo the suffocating relationship between these two grandiose men. It is a brutal power struggle played out in a coliseum of the imagination—László’s as channeled by Becker.

From left: Cat Cairn: The Kielder Skyspace by James Turrell, 2000; a scale model and a set for The Brutalist (photos courtesy of Judy Becker)

How did you and Brady Corbet come together for The Brutalist?

I’ve been wanting to work with Brady for years, ever since I saw Childhood of a Leader (2015). I’m very director-driven when it comes to who I want to work with and the projects I want to do. With The Brutalist I first thought, “Wow, that’s a great title!” and hoped there’d be brutalist architecture in it. I got the job talking with Brady on the phone. Then we met in New York, where he asked me to start by designing the Institute so that he and the team could figure out how we were going to do it, what we were going to build and what we were going to do.

What went into your first ideas for the Institute?

Because I needed to design this building, I pulled a lot of disparate stuff. I looked at a lot of concentration-camp imagery because I had to incorporate that reference into the building. That was scripted—that the building incorporates this idea of the two concentration camps, and László and Erzsébet communicating with each other. Then I was working with a lot of ideas about the symbolism of the cross, and I started with trying to figure out how to incorporate a hidden Star of David into the architecture, too. I didn’t end up doing it, although I thought about telling people I had and that they should look out for it.

Were you searching out the styles of particular architects?

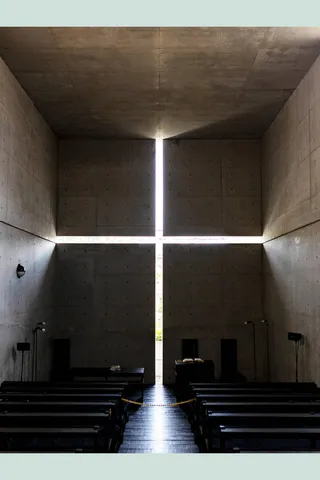

I turned more to architecture and architectural references. I wasn’t thinking so much about László’s generation of architects specifically, but of a generation like Tadao Ando’s and artists like James Turrell and some conceptual earthworks artists. I also thought of Harry Weese, the architect of the Washington, DC, metro system—he was an interesting brutalist American. I was just reaching into my head for inspiration. I didn’t say to myself, “Let me get out the brutalism books and design this thing.”

“I wanted it to feel like a giant factory-slash-crematorium on top of a hill.”

What did you want the building to feel like?

I wanted the Institute to be very utilitarian-looking. I wanted it to feel like a giant factory-slash-crematorium on top of a hill. And to be this big, almost “fuck you” to Harrison from László, but that Harrison wouldn’t know it. Harrison thinks he’s getting this monument to himself, but really it’s almost a Holocaust memorial that László was building.

What kind of language were you and Brady using to describe the look of the film? Were you swapping lots of pictures or was it a more verbal process?

Both. Brady would text and email me pictures [of building details] that he saw and things that could be incorporated. A lot of it was just ideas of things he liked, so not specifically for the production design, more ideas that would influence the look of the movie. I love looking at imagery and I love very visual directors like Brady—when you’re working with someone like that, you know that you can figure out a way to make it work. It might not be the scripted or the conventional way, but you’ll figure it out. I mean, I think that if he’d said, “We’re going to build the whole Institute, full scale, out of concrete,” that would have been crazy, though!

You left the concrete mixer at home for this one, then?

Exactly. Brady knew we couldn’t build the whole Institute. I’ve definitely turned down jobs that I thought were unrealistic, but this wasn’t one of them. So it was a great process and he’s very, very collaborative. He really let me do my job and trusted me with a real give-and-take of ideas.

Did you try to think of what László, the architect, would have built? Did you try to inhabit his character a little?

Inhabiting László was a really important part of it. I really did try to tell his story through design and tried to be him as best I could. And it seems hard, because he was from a different era and was a highly trained architect at the Bauhaus, and he’d been in a concentration camp for a long time. How could you be that person? It’s just so not me, but I tried to take what he had been through and imagine how that would have affected his work.

From left: a scale model and a concrete model for The Brutalist (photos courtesy of Judy Becker); the interior of Church of the Light in Ibaraki, Japan, designed by Tadao Ando

The library that László builds for Van Buren is a totemic room in the film and the backdrop for a pivotal scene in which he meets Van Buren for the first time. What went into this construction?

The main description in the script was vague: that he builds some shelves and the thing opens up like a flower. I knew it needed to be simple and modern. It wasn’t brutalist, it was just a job for László—it was a gig—and it was still at the early point of his life in America, so it’s really mid-century modernism. We went to Hungary and scouted this large house for Van Buren. The one room that would work for the library was a glass winter-garden conservatory, and of course you couldn’t hang shelves on the glass walls. I got inspiration about these angled cabinets that would solve all the problems. They would look modern, they’d change the shape of the room, and then the doors could open up like a flower. It all came to me at once, right there in the room. Then figuring out how to execute it is the difficult part, but we did it and it was beautiful. And the special effects guy did a little rig where you just pressed a button and it opened up. So gorgeous.

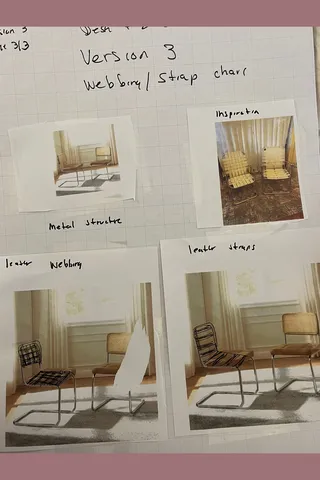

And then there’s a beautiful modern chair—like a Marcel Breuer design—set in the middle of the library that suggests an analyst’s couch and seems to invite the idea of self-reflection and self-inspection. Is there any sense in that?

It wasn’t on the tip of my tongue, but it could very well have been on Brady’s and Mona’s, because they wrote that the piece of furniture was like a chaise longue in the script. They were thinking a lot about psychology when they were writing, and I believe they could have intended that. It’s a brilliant thought because it makes so much sense for the character. Harrison is not a reflective person or anyone who would even think about therapy, but you could see László try to almost trick him. Like, “Oh, this looks comfortable,” but really he’s saying, “You need some help.”

Another important scene is when László has to pitch the Institute to the townsfolk, for which he—and therefore you—built a beautiful architectural maquette. I guess you had to spend more time perfecting the model as it was being shot?

Yes, I mean we never built the Institute. The Institute is represented in the film through drawings and models, with the models made by professionals. So there was that one and another, much bigger model that you see as the Institute in the film, but you don’t see it as a model. It was about nine or 10 feet long, and it was shot for the time-lapse sequences of the Institute getting built. That was a much bigger model with a concrete treatment on it. So the Institute was played by a model in several different ways.

From left: the exterior of the furniture shop and a model for an interior in The Brutalist (photos courtesy of Judy Becker)

Did you have to work with Adrien Brody on how to deal with the model for that scene? He, as László, obviously needs to be convincingly comfortable with its workings.

We did, when László talks about the square footage of this area and that detail and how the marble will work. We had to get out our calculators and figure that stuff out, because I don’t think some of it was in the written dialogue. Then, for when he turns the model around, we had to run out and buy a lazy Susan, and we talked about how to turn it and looked at the different pieces and played with it. And we worked together on presenting the model, which was fun because Adrien’s pretty knowledgeable about the arts and architecture. His mother’s a photographer and he’s a painter, so he’s pretty attuned to all of that. But then dealing with a model that comes apart and has pieces? Anyone has to be shown how it works, because it even had towers that you could take in and out to show the interior—like a little dollhouse, but brutal.

The furniture in the film seems to reflect character. László builds chairs out of modern, tubular steel, as seen in the library, while his cousin Attila sells brown, old-fashioned furniture. What were your ideas here?

Yeah, you could call Attila’s stuff American colonial furniture, I guess. I wanted it to look American and ugly and middle-class and awful. I’m not trying to be derogatory, but I just wanted it to be the opposite aesthetic [of László’s], to really represent America and show how Americanized Attila has become. We had to fly it from Canada, where my set decorator is from, to Hungary. She bought it from Craigslist and Facebook Marketplace, and she just went around with her minivan to pick it all up. We filled a container with that and some vintage American wallpaper and fabric, and anything that we couldn’t find in Budapest, and shipped it over.

Attila calls his furniture store Miller & Sons because he thinks Americans will feel comfortable with the name, but that’s also his own self-mythologizing, isn’t it?

Yeah, I mean they changed their name to Miller & Sons on the sign, and there’s no Miller and there are no sons. I had wanted to do a “ghost sign,” where you see a trace of the old signwriting underneath. I wanted you to be able to see “Molnar” there, but the sign construction took time. I asked Brady if we could have him do a name change, and then he came up with all of that stuff about Miller, which was great. Attila wanted to escape the past, which is understandable. I’m second- and third-generation American and I know my relatives wanted to just forget about, just erase, where they came from. So that’s a pretty common thing.

From left: reference materials and props for The Brutalist (photos courtesy of Judy Becker)

Without wanting to be too personal, Judy, does your family have a connection with any of the topics in the film?

Well, I come from a Jewish family who came over [to the U.S.] at a different time, at around the turn of the 19th to 20th century. So they weren’t directly involved in the Holocaust, but they were persecuted. I think that their attitude was similar. I had a great-grandfather who came over as a child, and when I would ask him where he was from, he wouldn’t tell me, but I knew he was from Romania. I was really interested in Eastern Europe and I wanted to know, and I wanted to visit. He would say, “You don’t want to go there, they hated the Jews. I’m not telling.” They wanted to forget about the old country and just be Americans. So yeah, I could identify with it. The Holocaust was something I was told about as a too-young child, and my mother would describe to me in detail how people were killed in the gas chambers. I was terrified to take a shower. So I could, unfortunately, immerse myself in that when thinking about designing this film, and especially the Institute, and thinking about what László went through. It was very emotionally difficult for me when I was doing that, but it also helped me understand the immigrant experience. It doesn’t feel that far off to me. My dad was the first generation of my family born in America, who became the generation that went to college and became professionals, and the generation before him managed to become entrepreneurs, perhaps. I find that fascinating because it always follows the same trajectory—and then I get to be the arty third generation. It’s really interesting to see how that works over and over again, if you’re lucky enough for your family to have the opportunity to become citizens. It’s obviously such an important topic right now in America. So yes, there was a lot about my personal history that let me into László’s history. Not directly, but indirectly for sure.

![<I>We Need to Talk About Kevin</I>, dir. Lynne Ramsay, 2011]() We Need to Talk About Kevin, dir. Lynne Ramsay, 2011

We Need to Talk About Kevin, dir. Lynne Ramsay, 2011![<I>American Hustle</I>, dir. David O. Russell, 2013]() American Hustle, dir. David O. Russell, 2013

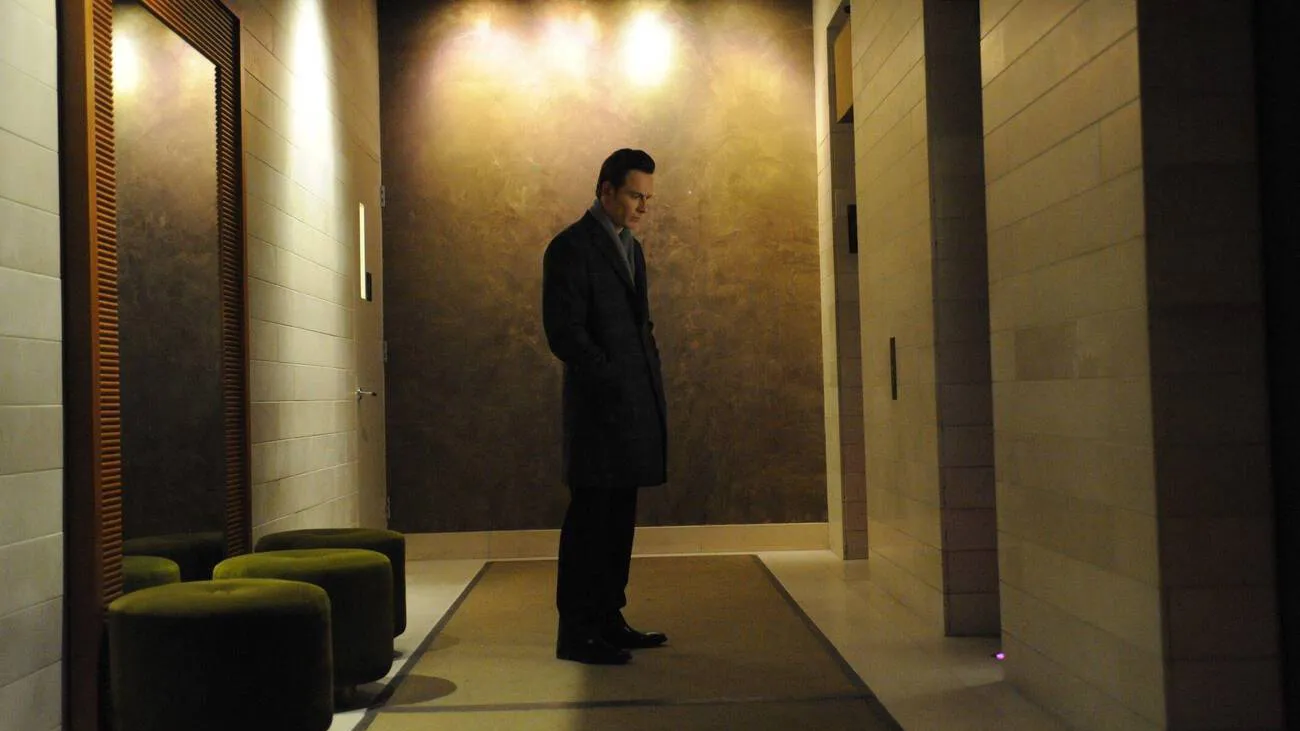

American Hustle, dir. David O. Russell, 2013![<I>Shame</I>, dir. Steve McQueen, 2011]() Shame, dir. Steve McQueen, 2011

Shame, dir. Steve McQueen, 2011![<I>Carol</I>, dir. Todd Haynes, 2015]() Carol, dir. Todd Haynes, 2015

Carol, dir. Todd Haynes, 2015

Your résumé contains such a rich range of films, from the lush 1950s palette of Carol to the flinty Western textures of Brokeback Mountain. Is there a red thread through your practice?

I definitely approach everything in a naturalistic way, and I always think about the reality of the world I’m creating. I really don’t want the design to be visible as “design,” except when it needs to be. I mean, obviously this movie is about an architect, so we’re looking at his designs as part of his profession. But I don’t like things that call attention to themselves for no reason, where the audience is talking about, say, bright red walls with paintings on them and forgetting about the story. I want my work to be organic with the rest of the craft of the movie, the storytelling, with the actors and with what the director wants. In the end, I want to work with directors I love, making the kinds of films I really want to see.