Great Theaters: Cinémathèque de Tanger

By Negar Azimi

negar azimi

How artist Yto Barrada transformed a neglected Art Deco cinema into a community anchor and gateway to revolutionary ideas

April 8, 2025

![]()

Cinémathèque de Tanger

![]()

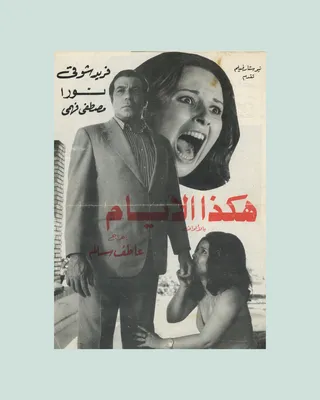

A vintage poster from the Cinémathèque de Tanger collection

I've known the artist Yto Barrada for nearly two decades and always approach our encounters with a mixture of excitement and trepidation. Talking to her is like standing in the path of a scintillating torrent of words and thoughts and images. Ideas materialize in thin air and have the power to carry you away.

Barrada’s early work traced the titanic shifts that her hometown of Tangier, Morocco, experienced in the early 2000s. A storied port city that has been ruled by successive empires, it is also a heartbeat away from Spain, making it a place of both limbo and longing for those who dream of reaching Fortress Europe. Through photography, film, printmaking, sculpture and printed matter, Barrada’s affecting art has immortalized Tangier’s peculiar psychic geography—its status as a site of perennial projection. Her projects have also gone on to engage a wide range of other themes, often in and around the legacies of colonialism, from the history of toys to the clandestine trade of fake fossils.

But her art career is just one of her two life projects. The other, which has occupied her head and heart since 2003, is the task of reviving a crumbling 1930s-era Art Deco cinema in Tangier’s Grand Socco, or central square. Dubbed the Cinémathèque de Tanger, the space has become a focal point of cultural life in the city, its cinema and adjoining café perennially bustling. With its rare and idiosyncratic programs of experimental, documentary and classic films from around the world, the Cinémathèque has spawned generations of discerning audiences. A filmic renaissance, if you will, on the shores of North Africa.

Yto Barrada

Yto, you just came back from Tangier. Tell me, what were you doing?

I was greeting the worms who will inhabit my worm-composting station.

I assume the worms are related to the Mothership, your Moroccan home and creative laboratory, and not the Cinémathèque.

Everything is part of everything. Everything connects. Ask George Clinton.

Good answer. Could you tell me a little bit about the Mothership, which I gather is your latest initiative?

Because my kids go to school in New York, our summer house in Tangier is empty much of the year. It’s a former gardener’s house that overlooks the Strait of Gibraltar, where Hercules famously separated Europe from Africa. It’s my favorite place on Earth, and I jumped from wanting to share it with other artists to creating the Mothership—thanks again, George Clinton—which is a residency program where people could stay for part of the year to work. There’s a vegetable garden, a flower garden, but also a dye garden, mostly because I’ve been studying natural dye techniques for the last decade. I thought this place, the Mothership, could become a lab—a place to rest, to teach, to study the land, and for residents to come and work in Tangier. Its manifesto will be written by those who come. Our first round of residents were four textile conservators, including one working on Marie Antoinette’s curtains at Versailles and another who had restored Michael Jackson’s glove. Of course, we called them the Fab Four.

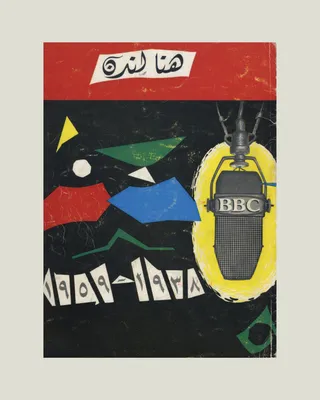

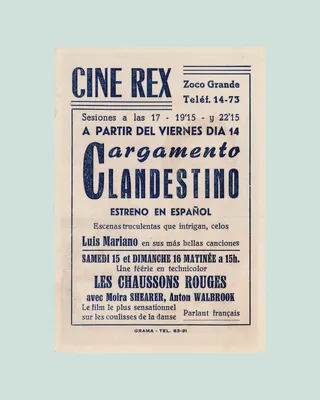

Images from the Cinémathèque de Tanger collection

You say everything connects, but I would suggest that the beating heart at the center of the Yto Barrada enterprise in Tangier is the Cinémathèque. Could you narrate its birth for those who know nothing of it? And situate who you were in the world when you embarked on the project?

I think this story has a good beginning—the way I remember it, anyway. I come from a family of storytellers, so you can expect a bit of rewriting—

Embroidering!

Embroidering. In the 1990s I was studying in France and practicing photography on the side. My mother, a transplanted Tangerine, is a psychotherapist and an activist who started by building a shelter for street kids and kids in transit, meaning kids doing everything they could to cross the strait to Europe. One summer her team carried out this big survey, interviewing tons of kids about their lives. I moved back to Tangier to give her a hand. One thing led to another, and one day I noticed that the old Cinéma Rif was for sale in the main square of Tangier, just across from the gates leading to the casbah.

A vintage poster from the Cinémathèque de Tanger collection

“The hope was that along the way we’d be able to pass on dangerous ideas around freedom, independence, subversion.”

The gate where Jane Bowles was famously photographed with her lover Cherifa.

Exactly. You always find the polyamorous angle, don’t you? [Laughs]

What was the city center like at the time?

Let’s say it wasn’t the scrubbed Tangier that you see regularly featured in The World of Interiors. There had been a bustling marketplace in the main square back in the ’50s, but it had since been shuttered, and by the ’90s replaced by a garish parking lot for buses. Still, the location of the cinema, which overlooks the main square, is special. It’s where the old city meets the new city.

What did you know about the cinema itself?

It was called Cinéma Rif and looked very much like many old movie theaters all over the country: Art Deco, wooden seats, mostly full of smoking men, teenage boys smoking hash. The structure itself had been built in 1938. You could say the entertainment was both on the screen and inside the space. At the time, the cinema showed Bollywood films clumsily subtitled in two languages, French and Arabic or English and Arabic, depending. You’d pay to see two films. It was very cheap. All the kids knew the songs by heart and worshipped at the altar of Bollywood stars like Shah Rukh Khan. Lots of kids. The cinema door still had a stick attached to it.

What was the stick for?

To get the kids in line, of course!

Oh là là. I know from a book you produced that Tangier was once the capital of cinema in Morocco. What happened?

It was. Morocco’s first printing press was established there back when the city was an international zone. Its first film festival was in Tangier, too. At its peak, the city had some 25 cinemas. The Alcazar, the Mauritania, the Vox, the Lux. People drove big shiny Chevys and Renaults to the movies, dressed in jackets and ties. Each cinema specialized in a different program. Some would play only Egyptian or American films, others played matinees in Spanish, and still others in French. Most of the others are long closed or have gone multiplex. Ours, the Rif, specialized in Bollywood. In the cinema archive we have a poster from the time Roberto Rossellini’s Europa ’51 played at the Rif.

I love that. As if each cinema reflected a piece of this dense international city. What changed?

Satellite dishes and DVD players, I suppose. By the beginning of the 1980s, most cinemas had closed because of the popularization of television. Then Bollywood often took over those cinemas that remained.

![]()

A vintage poster from the Cinémathèque de Tanger collection

![]()

The Cinémathèque Café

Besides Bollywood, what sort of cinema did people in Tangier have access to at the time you set about launching the Cinémathèque? What was the need—or rather, the opportunity?

There was absolutely no art-house and no local cinema. Everything felt a little bit mediocre. Very commercial, very boring, not challenging. Tangier’s intelligence was insulted! That said, good Moroccan films were beginning to have a career on the festival circuit.

Even though they weren’t visible at home.

Exactly, and to that you can add Iranian cinema, Senegalese, all the cinemas of the south. They were hardly visible “at home.” I should add that there had been a long and important history of ciné-clubs in Morocco, small associations where people could gather to discuss cinema, but because they were often aligned with political agendas and activism in universities they were considered a threat and weren’t encouraged from above. For many reasons these little fires of intense cinema culture or art-house cinema culture, world-cinema culture, were almost dead. Our intention was to turn the fire back on under them.

From what I understand, as much as Tangier has been a haven for both Moroccan and expatriate artists, from Paul and Jane Bowles to William Burroughs to Mohamed Choukri, it was long marginalized by the state, unloved by the former king, written off as a seedy port town replete with pirates and bohemians and homosexuals.

Tangier was the banished city. It was peripheral, outside the zone of influence, which is to say there was zero attention from the central government, zero investment. Of course, things would have been vastly different if the cinema had been in Casablanca, the economic capital. For years people would say, “Why don’t you do the same thing in Casa? There’s no one in Tangier interested in what you’re doing!”

How did you deal with that line of reasoning?

I was stubborn. I said, “We’ll create an audience.” That’s why we started a kids’ program.

Can you tell me about that?

We’d introduce a film every week, every Sunday morning, and work through the history of cinema. The film could be Charlie Chaplin, [Abbas] Kiarostami, some classic animation, The Red Balloon, Zazie dans le Métro. We had this—what’s his name, the Rogers fellow from American TV?—to run them.

You must mean Mister Rogers.

The equivalent of Mr. Rogers from Moroccan television.

Where did the kids come from?

We didn’t want the privileged kids from the private French or Spanish schools to be the only participants, so we also invited kids from the nonprofit my mom was running. It was a beautiful mix, a crowd of almost 300 children.

Yto, so much of your own artwork has been rooted in the negotiation of obstacles—economic, political and so on. I think it’s contiguous with the work of opening this improbable art-house cinema in a city—and a country—where there wasn’t an obvious audience, where there were legion bureaucratic hurdles and where people were always telling you that you were setting yourself up for failure.

I came back home to work on the project, mostly because working on the Cinémathèque from Paris had become impossible, given all the red tape. We had no money, but here was this incredible cinema for sale and we had to believe that we could make it happen. I had zero experience in cultural leadership. It was a friends-and-family project. So many people helped in whatever way they could, from the renovation plans to the programming to choosing the colors on the walls.

What was your vision for the Cinémathèque?

The idea was to create something much more powerful than a simple venue for entertainment. We wanted the cinema to open onto the world, especially because Morocco’s borders were closed. Don’t forget that Tangier is only 15 kilometers from Europe. On a clear day I can see Spain from my window. But it’s a one-way strait. I can travel across because I was born in Paris and have a European passport, but most people don’t have this luxury. So our idea was to bring the mountain to Mohammed, as it were. Since everybody is dreaming of getting out, we thought, Okay, let’s make something extraordinary right here. A place where people can meet. A place where the kids in town could work and learn and meet filmmakers. That’s why I say our vision was both very ambitious and a bit ridiculous, because freedom of movement is obviously what people need most.

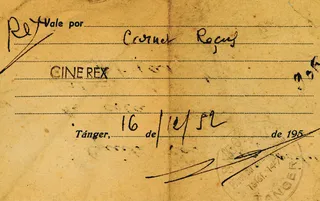

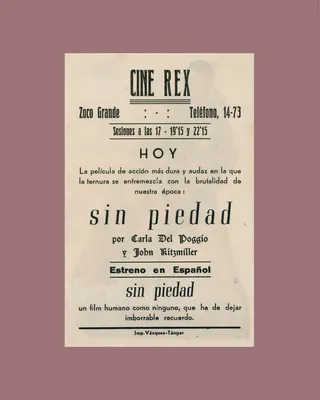

Flyers for Cine Rex

“The idea was to create something much more powerful than a simple venue for entertainment.”

I’m thinking of “the smuggler” as a construct, a figure who makes cameos in your art. And here you are smuggling in—

Ideas.

Like contraband.

Like contraband. The hope was that along the way we’d be able to pass on dangerous ideas around freedom, independence, subversion.

Can you talk a little about the programming, what makes it unique?

The programming has always been subtle, a little explosive, depending on how you see things. If there’s a Fassbinder retrospective, many will simply see a German filmmaker, but of course there’s a lot more going on between the lines. We’ve had cycles of Godard, Tati, Djibril Diop Mambéty, Pasolini, Youssef Chahine, Chantal Akerman. I think in the long run that subtlety laced with explosiveness is our identity, and that’s what I’m trying to keep afloat today.

That sort of trafficking in, let’s say, dangerous ideas, is that something that ever became an issue vis-à-vis, I don’t know…I hate to ask this question, because it feels like such a cliché when speaking of the Middle East and North Africa—

Censorship?

Yeah.

Oh, yeah. All the time.

How would you negotiate that?

I’ll tell you a story. A friend who used to work at the Tate Modern, Stuart Comer, came to Tangier a few years back with rare Oskar Fischinger visual music from an archive in L.A. They had to be brought by hand, because they were on film. We had a digital copy ready for the censorship authorities in Rabat, but at that time, before the advent of the fast train, there was a three-and-a-half-hour drive to Rabat. So it was seven hours back and forth to go to the censorship bureau, and we were tight on time. What do the censors see? They see circles and squares dancing! If you haven’t seen it, Fischinger’s visual music went on to be added to Walt Disney’s 1940 Fantasia. All music and abstraction. Well, they couldn’t figure out what the hell was going on, so they didn’t give me the permit for the screening on time.

Heathenous abstraction! Hardly sexy.

Oh, but I haven’t yet told you about the time we had to manually cut out a blow job from a Chilean film. We were on the phone for hours with the woman from censorship as she told us exactly where to cut. Her name was Madame Zizi. This detail will only be hilarious for French speakers. [Laughs]

Can we speak a bit about the Cinémathèque’s audience? I feel like one of the great victories of the space is that it could have very easily become an expatriate hangout, but instead, from the beginning, it seems to have been integrated into a local idiom and scene.

Well, the girls came over. That was the miracle.

Tell me about the girls.

Young girls, mostly teenagers, came to the cinema en masse to do their homework in the café. Normally in Moroccan cafés, girls don’t hang out. And if they do, they stay inside; they don’t sit on a terrace! Maybe they came to us because most of us working at the cinema were women. That could be it. We were present and loud. Of course, economically it wasn’t great for us, because the girls would order two coffees and spend the day doing their homework, playing cards, smoking cigarettes. [Laughs]

What happened to the girls?

They grew up, and they’re the ones running the cinema today.

![]()

The lobby of Cinémathèque de Tanger

![]()

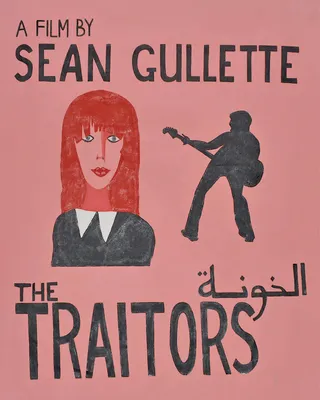

A poster by Abdel-Mohcine Nakari

![]()

Cinémathèque de Tanger in 2011

That’s fabulous. And there are new boys and girls in their place. Last time I visited, which was just before the pandemic, I was struck by how crammed the café was with young people. It made me happy. Tell me, how did you go about building an audience for art-house cinema?

I believe there’s an audience for anything if you introduce it. If you’re there, if you talk about it, if you present it with encouragement, if the tickets are cheap, if the cinema is heated. Cinemas have to be comfortable! Only then can you show a three-hour black-and-white film. Even if they’ve never heard of the filmmaker, the kids are willing to sit through it because they trust you.

You spoke of turning your gaze inward, as it were, by which I mean showing Moroccan, Brazilian, Iranian and African films. A sort of decolonizing of the canon.

It’s happening, slowly. Younger kids are less locked into the cinema of Mother Europe. They’re more interested in their own heritage. I remember when Martin Scorsese started his foundation, and the first film he restored was a Moroccan film, Trances, from 1981—a documentary about the band Nass El Ghiwane by Ahmed El Maanouni. People here were like, Wait a minute. Seriously? He didn’t find anything else to preserve? There’s so much that remains underappreciated, from the films of Ahmed Bouanani to those of Mostafa Derkaoui that are getting new attention. It sent a strong signal.

What’s the state of the Cinémathèque today?

On the one hand it’s a success: It’s a destination and an institution in the city. But it’s still very fragile. The city has grown, and with that have come new cultural centers. And then came the blockbuster cinemas. The government is basically happy to support the big entities and let the scrappy nonprofits die. So it’s always a battle. But we remain the only place where you have film programs on architecture, where you have documentaries and films on art, and where you can find all kinds of classes and workshops.

Not to romanticize being fragile and precarious, but on some level—

No, there’s nothing romantic about being broke and exhausted! Or not having heat or AC in the cinema. Can you imagine? You asked about our situation today. Today is a big rainy day. The sky is falling and there’s flooding in both cinemas. There’s always something. Economically, we’re badly in trouble after being closed for a year and a half [during the pandemic].

I’m making a pitch on your behalf for potential benefactors.

Thank you.

Yto, a final question: I think it’s fair to say that you’re unusually invested in recovery projects. Years ago, you and I met through the Arab Image Foundation, an unusual artist-driven archive for which you had collected hundreds of rare photos from Iraq and elsewhere. Then there are your recent efforts to bring attention to Bettina Grossman, an artist who lived for decades in the Chelsea Hotel, where she produced fabulous and fabulously special abstract and conceptual drawings, sculptures, photographs and films. The list goes on and on.

I like to dig into things that already exist. Who needs new ideas? There’s enough here to conjure with.