Morocco's Dissident Filmmakers

By Mohamed Hassan

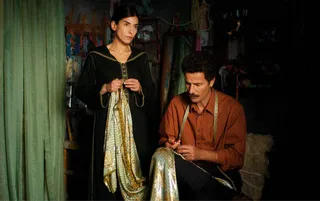

The Blue Caftan, dir. Maryam Touzani, 2022

Morocco’s Dissident Filmmakers

A new wave of indie cinema confronts long-held conservative taboos head-on

By Mohamed Hassan

October 25, 2024

There is an easily overlooked scene at the heart of Moroccan director Maryam Touzani’s quiet 2022 masterpiece, The Blue Caftan, in which a seasoned tailor, Halim, and his young protégé, Youssef, talk about how to make cuts into fabric. “Leave yourself a centimeter, a margin,” Halim says. “But if you cut too much, you can’t go back.”

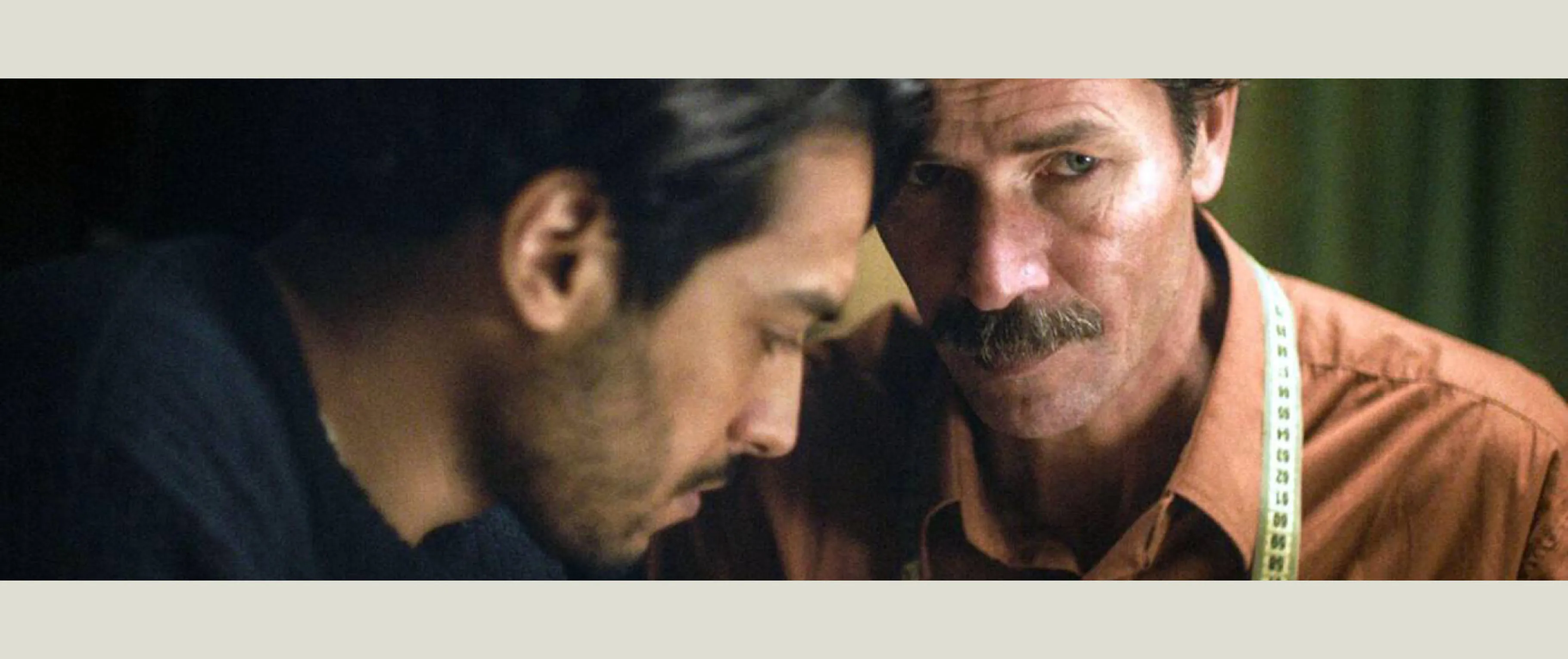

From left: Lubna Azabal and Saleh Bakri in The Blue Caftan; Ayoub Missioui in The Blue Caftan; Lubna Azabal and Nisrin Erradi in Adam

The conversation circles around the crafting of the titular garment, a traditional Moroccan robe worn for special occasions such as weddings or funerals. The client is extremely picky and shows up at the store Halim runs with his wife, Mina, to check on the progress. For the survival of his business, Halim must perfect the caftan using the artisanal skills he's nurtured over a lifetime. For the sake of his marriage, however, he must exercise even more caution. Hidden between the lines of his seemingly mundane advice to the novice Youssef is another, more nuanced conversation between two men slowly falling in love.

In a country with punitive laws criminalizing homosexuality and prostitution, Moroccan cinema has been staging a not-so-quiet revolution. In recent years, homegrown independent films have explored subjects and sensibilities considered taboo long before the invention of celluloid. A little over a decade ago, scenes of police corruption and sex trafficking shocked audiences in films like Zero (2012) and Death for Sale (2011). Their successors are pushing even deeper into the social fabric, broaching daring conversations about sex, anger, shame and rebellion. One of the chief instigators of this cultural sea change has been Casablanca-based cinema legend Nabil Ayouch, who has been celebrated globally as a voice for the country’s emerging industry, even as his films attract fierce criticisms and anger within Morocco.

Ayouch, a French-born filmmaker who is the husband and frequent collaborator of Touzani, gained international attention with the French-Canadian production Whatever Lola Wants, his 2007 film about an impulsive American twentysomething who travels to Cairo with dreams of becoming a belly dancer. The film performed well in France but failed to impress some critics, who felt it held back its most poignant social critiques. Instead, it’s Ayouch’s Moroccan films that have made a mark and cemented his position as both agitator and visionary. These include Ali Zaoua: Prince of the Streets (2000), about a group of homeless youth in Casablanca, and Horses of God (2012), about the 2003 Casablanca bombings. Six of Ayouch’s films have been selected for Academy Award submissions despite the continued backlash they have received in Morocco. His film Much Loved (2015), an unflinching portrayal of sex work and homosexuality based on Touzani’s documentary Sous ma peau vieille (2014), shocked audiences and prompted death threats against both the director and the film’s lead actress, Loubna Abidar. The film was quickly banned by Moroccan authorities for its content, which included portrayals of rich Saudi clients soliciting prostitution. Ayouch’s Casablanca Beats (2021) sought to place the microphone in front of young Moroccans. Shot at Les Étoiles de Sidi Moumen, a cultural center cofounded by Ayouch in the Sidi Moumen district of Casablanca, the film featured a cast of first-time actors playing versions of themselves in a hybrid of scripted and free-flowing scenes that showcased a new generation grappling with the rules governing their working-class neighborhoods.

“Moroccan cinema has been staging a not-so-quiet revolution.”

Despite Morocco’s strict laws and the steep societal backlash, a new crop of risk-taking filmmakers has followed Ayouch’s lead, dancing and raging against tradition and pushing their country toward self-reflection. Two recent standout examples were focused on LGBTQ+ issues. The Blue Caftan is a film that demands patience and focus. The story it tells is a quiet revelation, tiny tremors below the surface signaling an incoming earthquake. At its center is the decades-long marriage of Halim (played by Saleh Bakri) and Mina (Lubna Azabal), a union that has sustained itself on kindness, mutual recognition and the dying art of traditional tailoring. The couple woefully mourns the industry that has abandoned craft in favor of machinery, detail for convenience. It’s a struggle Halim is waging internally, a man truly in love with his wife but who cannot resist the temptations provided by other men in the hushed safety of the hammam. Amid the fog of vapor in the male spa, he allows his own hazy sexuality to breathe, even if only in these secret rendezvous with strangers. Outside he is the introverted family man, the devoted husband, the talented artisan sought out by local customers—a product of a society desperately hanging on to tradition amid the vertigo of a fast-changing world.

When Halim becomes drawn to his tender and devoted apprentice Youssef (Ayoub Missioui), he finds it impossible to hide his flourishing affection from his keen-eyed wife, whose own vain attempts to push Youssef away only deepen the cracks in their marriage. The three continue to dance cautiously around each other, trying but failing to guard what’s in their hearts. The film is anchored by two riveting performances—Azabal’s breathtaking subtlety as Mina and Bakri’s devastating portrayal of Halim’s wordlessness. It is a masterclass of letting silence take over a screen while the subtext screams beneath it. Silence is a recurring theme, a mirror held up to Morocco’s own willful blindness to the ripples beneath the surface of society. Homosexual sex remains outlawed in Morocco. Not only that, but it is common practice for authorities to publicize the names of people arrested under these laws, exacerbating their marginalization in conservative society. No legal protections exist for recognizing queer identities or gay marriage, despite international pressure. In 2015, the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe called on the Moroccan Parliament to halt the implementation of punitive measures, but there’s little sign of progress.

Touzani has explained that she feels compelled to speak to this issue as a means of opening people’s eyes. Social issues are a central theme in her work, starting with her celebrated first feature, Adam, which told the story of a pregnant, unwed Moroccan woman who’s given shelter by a widowed baker. The story was inspired by Touzani’s own parents, who sheltered a heavily pregnant woman in Tangier when it was still illegal to have a child out of wedlock. The reason her second feature, The Blue Caftan, shortlisted for the 2023 Academy Award for International Feature Film, succeeds lies in its ability to broach sexuality with such gentle and particular care it almost feels like a love letter to the society and tradition it aims to confront.

On the other end of the new-wave aesthetic, The Damned Don’t Cry (2022) takes a different tack in revealing sexuality. British-Moroccan director Fyzal Boulifa’s nauseating cinematic road trip about a woman and her son on the fringes of society does away with subtlety and reveals its rage. Itinerant Fatima-Zahra (played Aicha Tebbae) and her teenage son, Selim (Abdellah El Hajjouji), cascade from one public shaming to the next, fighting for security and dignity in a society that has failed to make space for them.

The anger mainly belongs to Selim, who is coming of age surrounded by secrets—his mother’s and his own—and refuses to accept the lies that Fatima-Zahra has told his entire life to sedate his curiosities about the world. Once he learns that all the stories about his father were fabrications, and that his mother was raped in her village by an unknown assailant, he can no longer tolerate her attempts at romanticizing their unrooted life. At the same time, Selim’s teenage emergence into the world of work and men finds him stumbling naively from one misstep to another, having to learn quickly that his sexual curiosity must be guarded and that his honesty will be used against him—in one scene, he’s tricked into prostitution with a foreigner by a fellow Moroccan thought to be his friend.

The Damned Don't Cry, dir. Fyzal Boulifa, 2022

Boulifa is less concerned with romanticizing Moroccan heritage than dissecting its bleaker reality. His Morocco is one barreling into modernity, but its chief antagonists are not tradition as much as gender and class. The director’s characters have been ostracized by poverty in a society where financial independence is a patriarchal endeavor. Despite Fatima-Zahra’s attempts to live in her own feminist narrative (always dressed in decorative caftans and full makeup, a diva of her own making), she returns time and again to the reality of being an unmarried woman who cannot survive on her own. Thus she weaves stories to herself, to her increasingly skeptical son and to potential marriage suitors—tales where she is not the victim of circumstance and shame but a glamorous protagonist. In the end it’s reality that triumphs, and her refusal to acknowledge Selim’s own quest for truth that tears their family apart.

Selim is left to navigate the world on his own, finding momentary refuge in the home of Sébastien (Antoine Reinartz), a wealthy gay French traveler who appears liberated from the societal and economic confines that Selim and his mother cannot escape. His kindness and generosity first arrive as a form of salvation for Selim, who initially is free to express his sexuality, but soon finds that even under Sébastien’s roof he is judged by the Moroccan staff, and that while his new employer is unaffected by the suspicious eyes that circle them, it is Selim who must face the consequences. The film’s aching truth is that the journeys of mother and son are mirrors of one another, if only they can let go of their delusions to seek a shared understanding. (The film offers a scathing critique of the European fascination with Morocco as a playground for their adventure and self-discovery.)

![]()

Much Loved, dir. Nabil Ayouch, 2015

![]()

Whatever Lola Wants, dir. Nabil Ayouch, 2007

![]()

Casablanca Beats, dir. Nabil Ayouch, 2021

Essentially, both films reflect a country in quiet unrest. Its young are angry, railing against a monarchy that promised a prosperous future but failed to deliver it. Each year an alarming number of young men brave the unrelenting Mediterranean waters, desperate to reach Europe and its promises of economic, social and sexual freedoms. Morocco’s older generations are trying to hold on to their traditions, while their nostalgic portrait of a society slowly erodes around them and shame is the social currency that keeps it from falling apart. In one of The Blue Caftan’s most intimate scenes, Halim confesses to his wife that he has labored to suppress his sexuality his entire life, and even in his failure has continued to seek outlets far from the prying eyes of society. “I could have brought shame on your house, but I didn’t.”

One glaring defect of both films is the failure to address Islam’s role in Moroccan society. In The Damned Don’t Cry, the arrival of a devout bus driver into Fatima-Zahra’s life seems at first to offer her an avenue of salvation through marriage but then becomes an unyielding barrier that further alienates her son. We are left wondering whether the film intends to praise or criticize religion, and why it appears so alien to our protagonists. Similarly in The Blue Caftan, Mina is consistently portrayed through an almost saintly lens, often seen supplicating in the early hours of the morning, even in her ailing health. By contrast, her sleeping husband, Halim, seems indifferent to his wife’s spirituality. We’re never offered an insight into her relationship with Islam or what truths she finds in her marital predicament. We also don’t venture into Halim’s own relationship with faith, or how his closeted sexuality rests against it. Perhaps it’s enough to plant fertile ground for conversation and allow the audience to reach their own answers.