Top 10: Festen on Film Interiors

By Christopher Bollen

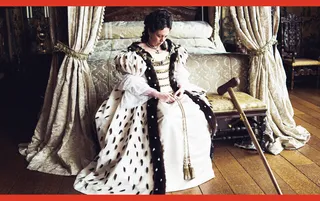

The Favourite, dir. Yorgos Lanthimos, 2018

Top 10: Festen on Film Interiors

Christopher Bollen

The cinematic atmospheres that make the French design duo swoon, from decadent palazzos to a vampire’s living quarters in Detroit

March 28, 2025

Hugo Sauzay and Charlotte de Tonnac of Festen (photo by James Nelson)

When Charlotte de Tonnac and Hugo Sauzay, the duo behind the French design firm Festen, conjured the tapestry-and-travertine interiors of the soigné hotel Château Voltaire and its brasserie on Rue Saint-Roch in Paris, one of their references came directly from cinema: Disney’s 1970 animated film The Artistocats. “It has small, intimate rooms, which is very Parisian,” Sauzay notes. De Tonnac and Sauzay, partners in both work and life, often mine films for inspiration points when it comes to their projects, ranging from restaurants to private residences—the blue of the furniture in Jean-Luc Godard’s Contempt, for example, or the frisson between modesty and opulence in the kitchen of Babette’s Feast. The pair are currently working on a slew of new commissions, including an 18th-century palazzo in Mexico City, a hotel in Gstaad and an eatery in London. Here, they share the design moments in cinema that have guided their choices on everything from carpets to furniture.

![]()

The ballroom scene in The Leopard

![]()

Crumbling grandeur in The Leopard

1. The Leopard, dir. Luchino Visconti, 1963

Sauzay: We just love the house. It’s exactly what you expect to see when you enter a beautiful old palazzo in Sicily [a majority of scenes were shot at Palazzo Valguarnera-Gangi in Palermo]. We have the book about this house, La Sicile au temps des Guépards [Editions du Chêne, 1999], and it’s a big reference for us, even if it’s really far from our style. We love how the baroque gallery of mirrors makes such a contrast with the more austere parts of the house. The dance scene in the ballroom runs almost 50 minutes, and the rooms just amaze us with all of their details: the Oriental carpets, the gilding, the Murano chandeliers and the floor of majolica tiles. Everything blends together to create a warm, golden color that is so enveloping and grandiose.

De Tonnac: We have a special thing for Italy, especially the fantasy of it.

“We love how the baroque gallery of mirrors makes such a contrast with the more austere parts of the house.”

Pleasures at the table in Babette's Feast

2. Babette’s Feast, dir. Gabriel Axel, 1987

Sauzay: Two years ago we started a project in Copenhagen. The project stopped, but this movie, which we watched while working, stayed. It’s almost à huit clos, all taking place in one room. It’s a story about strict Orthodox people in a little village on the west coast of Denmark. The room is really dark, poor and simple—

De Tonnac: And austere. It’s completely the opposite of The Leopard.

Sauzay: We like austerity because it really keeps to the basics of design. Kind of a Shaker style. In the film, Babette wins money and she’s a wonderful French cook and wants to make the perfect meal. So there is an opposition between the dark, austere surroundings corresponding to a modest, Protestant way of life, and the lively food and table decorations—fine porcelain in the French faience style, crystal glassware, the table silver and the cream-white linen tablecloth, which begins to show stains and traces of the guests to emphasize the shift between modesty and pleasure. So it creates a strong tension. That tablecloth in the house of The Leopard wouldn’t have the same impact.

![]()

The accumulated layers of Only Lovers Left Alive

![]()

A vampire at home in Only Lovers Left Alive

3. Only Lovers Left Alive, dir. Jim Jarmusch, 2013

De Tonnac: I really love this movie. It’s about two vampires who are hundreds of years old. One lives in Detroit and the other in Tangier, a city we love. So very opposite cities, and yet there is still a sense of nostalgia in both these settings and decor.

Sauzay: Because they’ve lived for centuries, there is a multiplication of layers in the rooms. One vampire is a musician, so he has an old Arabic-style lute that looks 200 years old, and he also has guitars from the 1960s because he’s a rocker. A lot of shots are filmed from above, so you see the rooms from the ceiling down and you get this accumulation of carpets on the floor. It’s kind of a mess, but it’s such a strong decor—one of those cases where the room really speaks like a character in the film.

Transcendent natural light in Barry Lyndon

4. Barry Lyndon, dir. Stanley Kubrick, 1975

De Tonnac: What’s very interesting in Kubrick’s movies is the accuracy of historical details. In Barry Lyndon, his accuracy extends to the use of light, with natural light and candlelight and how a scene would really look lit that way.

Sauzay: He used camera lenses designed for NASA because they were the only ones that could film with natural light and without the help of additional lighting.

De Tonnac: Kubrick is so thorough and precise, almost to a maniacal extreme, but it allows you to enter a complete atmosphere.

Sauzay: I think he had a designer’s eye. I read that when he made The Shining (1980), he sent his team to like 70 hotels in North America to take pictures to make sure they’d have all the details right. And then you have something like 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), with this immaculate, pure, simple white of a spaceship, and that’s a total atmosphere too, the coldness of space.

“Kubrick is so thorough and precise, almost to a maniacal extreme, but it allows you to enter a complete atmosphere.”

Strong architectural lines in Dune: Part 1

5. Dune, dir. Denis Villeneuve, 2021

De Tonnac: I don’t really like science fiction. But Dune was the first movie I saw after giving birth, and I remember sitting in the theater and being blown away. I don’t even remember the story. I just remember how stunning the sets are.

Sauzay: You see a lot of architectural references in it, like brutalist architecture or references to Frank Lloyd Wright. Again, I remember we were in the theater, and I was saying, “Look at all those details,” down to windows and handles, and yet it’s also this beautiful sprawling urbanism. The buildings are so massive and the people just look so tiny. It really messes with ideas of scale. It’s like the architecture is too big for humanity.

The pyramid staircase at Casa Malaparte in Capri, as seen in Contempt

6. Contempt, dir. Jean-Luc Godard, 1963

De Tonnac: We definitely chose this one for the house [Casa Malaparte in Capri, Italy]. We even have a photograph of it hanging in our office. The first time I saw the house was when I watched this film. One of our clients is a fashion photographer, and he knew our obsession with the place. He went there to do a shoot and gifted us the picture. What’s so interesting about the casa’s architecture is that it possesses the austerity of simple materials like terracotta-colored masonry and sharp geometric lines, but it still has such grandness, especially with the omnipresence of nature through its large picture windows. The monumental external staircase is almost a character unto itself, and it accentuates the characters’ feelings of coldness and isolation. The modernist furniture inside the house also has that sense of simplicity and sophistication, and many pieces, like the sofa, are done in a Mediterranean blue that we regularly use in our projects.

![]()

Historical decadence in The Favourite

![]()

Chess as visual metaphor in The Favourite

7. The Favourite, dir. Yorgos Lanthimos, 2018

De Tonnac: This film is on the list for its historical decadence. There’s so much richness in the decor, so much craziness and opulence. One of the most striking elements is the checkerboard floor that runs through several of the rooms—obviously the chessboard is a metaphor for the power games and manipulations between the characters. The tapestries and ancestral portraits hung on the dark wood paneling also reinforce the feeling of aristocratic decadence. The whole set really keeps with the emotional state of the main character because you also see cracks in the façade, the decay taking over the castle. It creates an exciting visual tension.

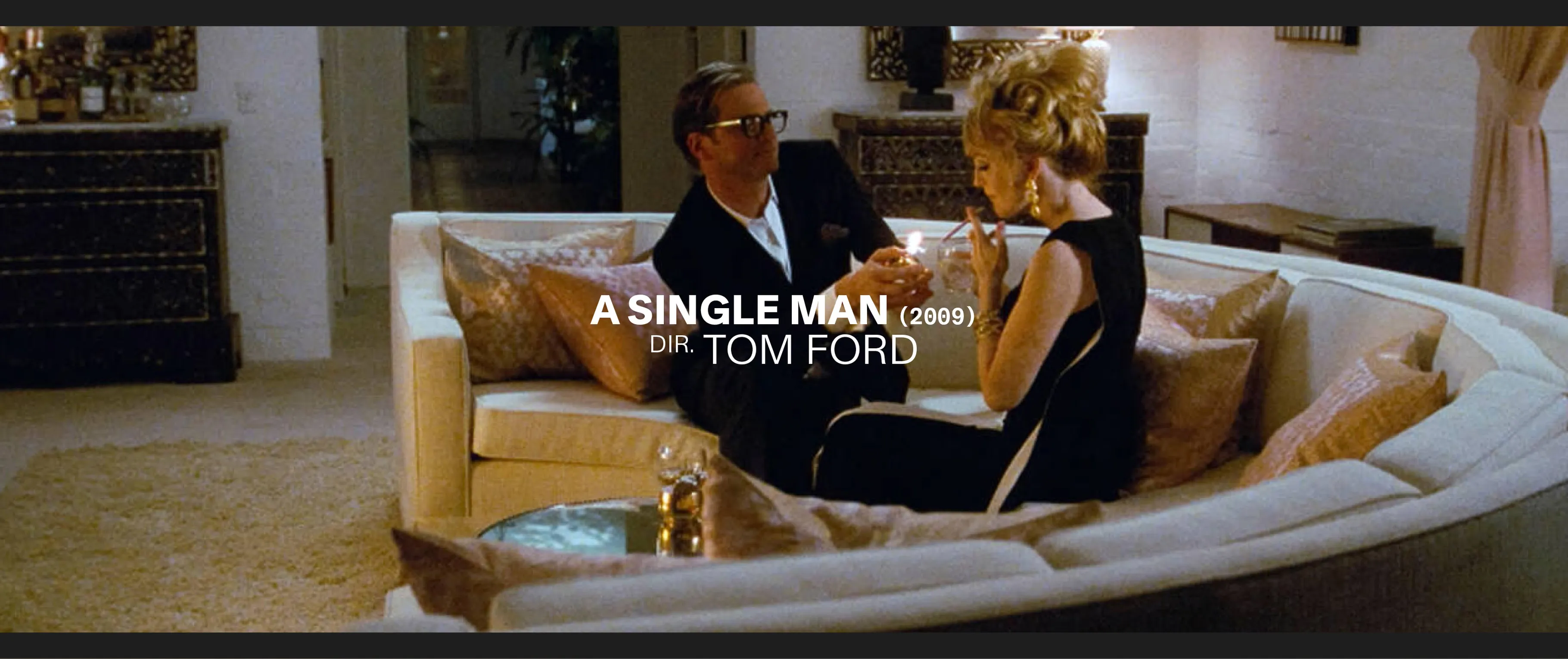

Mid-century elegance in A Single Man

8. A Single Man, dir. Tom Ford, 2009

Sauzay: We’ve had a chance to visit some of [architect] John Lautner’s houses over the years, and the house used in this film really is one of his most beautiful. It’s a period of architecture we really like, and we’re big fans of Lautner. The organic setting of the interior—dark, rich woods and the large windows that allow in light—creates a strong dramatic atmosphere. Also, the isolation of the house in nature really adds to the feeling of melancholy. But it’s also a sanctuary for the main character, removed from the rest of the world. We love that paradoxical feeling of rigidity and calm that comes with mid-century architecture and furniture.

De Tonnac: The house feeds into the larger aesthetic of the film, which is the eye of Tom Ford, his special touch for making every element so beautiful. You could argue it’s almost too beautiful, much like Luca Guadagnino’s films, because everywhere you look there is such attention to style and taste.

![]()

Visions of a urbanity in Metropolis

![]()

Scale and modernity in Metropolis

9. Metropolis, dir. Fritz Lang, 1927

De Tonnac: We are being good students by putting Metropolis on the list. You study this film when you’re in interior design and architecture school. It’s so avant-garde and opulent, with high society living in big skyscrapers and the lower parts of society in dark, narrow confines.

Sauzay: It’s a vision of a city of the future. This is long before Star Wars or Dune, complete with modern highways and bridges. It still looks futuristic today.

De Tonnac: It’s also black and white, which makes everything more dramatic.

Reflections of opulence and fractured psychology in Last Year at Marienbad

10. Last Year at Marienbad, dir. Alain Resnais, 1961

De Tonnac: The French love this film, and Alain Resnais is a very French filmmaker. It’s an absolutely beautiful film, highly aesthetic, shot in black and white, and all taking place at a grand old hotel—the film was actually shot in Bavarian palaces. The main character thinks he had a love affair with a woman who doesn’t remember anything about him. We don’t know which one of them is out of their mind. The decor is so elegant and theatrical, it’s almost unreal: elaborate tapestries, heavy curtains, crystal candlesticks. But the long hallways and formal gardens make the hotel feel like a labyrinth. The set amplifies the feeling of these characters being lost.