Top 10: Literary biopics

By Christopher Bollen

The Hours, dir. Stephen Daldry, 2002

Top 10: Literary biopics

By Christopher Bollen

Cinematic portraits that nail the writing life

July 18, 2025

“Do something,” Susan Sontag wrote three times over in her notebook as a goad to avoid laziness. Presumably by doing something, a prolific writer like Sontag meant sitting at her desk, working on an essay or a story. Of all the arts, it’s hard to think of a career less fit for cinema than writing. Painters can paint (see Pollock), musicians can play (all rock-band, singer-songwriter, or classical-composer biopics), and actors can struggle with extreme celebrity while striving for melodramatic fulfillment (from Frances and Mommie Dearest to Chaplin and Once upon a Time…in Hollywood). But writers are pretty much chained to their desks, tapping on a typewriter or scribbling on paper for hours on end (and that doesn’t account for endless bouts of staring). The literary biopic is a finicky film subgenre. The director needs to figure out how to bring the subject’s words to life while respecting the genius of their output even if, in person, their subject might be a cowering, neurotically shy mess. There have been some standout writer biopics, particularly involving authors who defined the 20th century—ironically, the period when cinema surpassed the novel as the chief form of popular storytelling. If one constant appears in such films, it’s the willingness of the filmmakers to treat writers not as secular saints but as flawed and fractured humans who often confuse their work with their personal lives. In doing so, filmmakers break a fundamental rule: that it’s the privilege of the writer to have the last word.

![]()

Gwyneth Paltrow and Daniel Craig in Sylvia

![]()

Gwyneth Paltrow as Sylvia Plath

1. Sylvia, dir. Christine Jeffs, 2003

From the opening scene at a party in Cambridge where Sylvia Plath (Gwyneth Paltrow) first meets Ted Hughes (Daniel Craig), the film overflows with nearly nonstop action. This frenetic energy is a surprise for a film that, at heart, charts the relationship between two neurotic, intellectual overachievers never far from their writing desks. In the first 20 minutes, there’s dancing, Sylvia biting Ted’s cheek, students climbing over walls, a poetry-club reading that could double as a rap-off, aggressive sex, and sailing on dangerous seas. The frenzy of these early scenes succeeds not only in establishing Sylvia’s youthful mania but eventually contrasts the deathly static, isolated psychology of the second half of the film, which is devoted to Plath’s spiraling depression. In this way, the film functions as a bipolar character study. Christine Jeffs does Plath’s poetry justice, cluing the viewer in on the symbiotic relationship between her life and her verse: how the death of her father in childhood leads to the poem “Daddy” and her unsuccessful suicide attempt at age 20 haunts “Lady Lazarus.” Through the film, there’s an impressive amount of effluvia from the literary world—rejection letters, book parties, a recitation of Robert Lowell, not to mention Paltrow at the kitchen table fighting writer’s block, staring out the window, nearly giving up. Toward the end, after Ted leaves her, the words finally flow, with recited lines from what will become her collection Ariel overlapping as Paltrow scribbles away in the dark. Plath became a literary icon, heralded as a feminist martyr suffering under the oppressive sexism of the 1950s. But Jeffs does a commendable job of keeping the scales balanced when it comes to the flaws of both parties (Sylvia is paranoid and controlling, Ted an egomaniacal philanderer). In the final scenes, after Sylvia has written her last poem, and before she tapes the kitchen door shut to keep the oven gas from seeping out, Paltrow is angelically shot bathed in gold light. In other words, she’d finally found peace. It might have been tempting to play up her suicide, but Jeffs denies us the morbid fascination of a death scene. We’re left remembering Sylvia not by her suicide (which became the most famous factoid in her biography) but in life.

.jpg)

Gary Oldman (center) in Prick Up Your Ears

2. Prick Up Your Ears, dir. Stephen Frears, 1987

Only Stephen Frears could turn the violent murder of a young playwright into an acid-tongued comedy that sticks out that tongue at British manners. Joe Orton (Gary Oldman) was the hotshot up-and-coming playwright of Swinging Sixties London, riding high on the success of his latest play, Loot, and penning a film script for the Beatles. The film starts with the close-up of Orton’s bloodied boyfriend, Kenneth Halliwell (Alfred Molina), who has just bludgeoned the playwright to death with a hammer. What follows is hardly the typical deification of a biopic. For one, we barely even get a hint of the subject of his plays, and scenes of Orton struggling with his craft are few and far between. Rather, it seems as if Frears has turned the entire film into a poetic homage to the writer, infusing it with the stylish irreverence and pitch-black comedy that made the playwright a sensation (a sample of the film dialogue: “I always wanted to be an orphan. I could have, if it wasn’t for my parents”). Prick Up Your Ears, with its crude, pop aesthetic and celebration of gay sex (then a jailable offense), allows Frears to revel in the rambunctious, wild-child spirit of the age. In a clever framing device, most of the work of writing depicted comes not from Orton but from his dogged biographer (Wallace Shawn). It is through the discoveries during his research that the audience is fed periodic flashbacks. Orton was murdered at age 34, but you get the feeling he would rather be remembered for his wry, cutting humor than his violent end.

Philip Seymour Hoffman as Truman Capote

3. Capote, dir. Bennett Miller, 2005

Philip Seymour Hoffman received an Academy Award for his portrayal of the mincing gadfly prince of literary high society. Hoffman embodied Truman Capote with such sadistic precision, down to his trademark sibilant voice (part lisp, part Southern drawl), that the writer appears as ruthless as the murderers, Perry Smith and Dick Hickock, who shotgunned the Clutter family in their Kansas farmhouse in 1959. Capote is, in many ways, a biopic of the book In Cold Blood, which the author wrote about that violent crime. The film opens with a discovery of the bodies and with Capote reading of the murders in The New York Times. It ends when the killers hang and Capote is free to write the end of the story. In between, Hoffman is at the center of nearly every scene. There is very little to like in this characterization of Capote—his need for attention, his lizardous charm, his endless self-pity at the expense of his friends. But there is still something about him to admire. Rewatching the film all these years later, I kept hearing Joan Didion’s line, “Writers are always selling someone out.” This is selling out on steroids, or call it “gay creative grit.” Capote himself acknowledges the similarity between writer and murderer at one moment halfway through the film: “It’s as if Perry and I grew up in the same house, and one day he stood up and went out the back door while I went out the front.”

“Rewatching the film all these years later, I kept hearing Joan Didion’s line, ‘Writers are always selling someone out.’”

![]()

Andrea Di Stefano and Javier Bardem in Before Night Falls

![]()

Javier Bardem and Johnny Depp

4. Before Night Falls, dir. Julian Schnabel, 2000

“Why do you write?” a friend asks the Cuban dissident poet and novelist Reinaldo Arenas (Javier Bardem) shortly before he escapes to the United States as a political refugee in Before Night Falls. His answer is simple: “Revenge.” Most writer biopics go to great lengths to showcase the exceptionality of their protagonist, but Julian Schnabel’s gorgeous, sweeping epic lingers on depictions of its hero at one with Cuba—whether it’s the rural beauty of his childhood (he carves his first poetry verses into the trees) or the rough, stylish urbanity of his adulthood. Arenas is no outsider, at least not yet. When Fidel Castro’s guerrillas take power, the poet is suddenly perceived as a social pariah—a dangerous gay counterrevolutionary who publishes his work overseas despite the ban on all output. Schnabel’s first success as a visual artist is evident in his painterly approach to the imagery of the film, particularly in contrasting poetic shots of waves, tumbling seas and thick jungles with the ungodly tight confines of a prison cell, which is where Reinaldo eventually ends up. Before Night Falls is about the detainment and exile of a political writer. But the film delivers Arenas’s struggle without getting weighed down with sanctimony or sermonizing. “People that make art are dangerous to any dictatorship,” an early mentor of Arenas declares. “Beauty is the enemy.” Schnabel marinates us in the enemy.

Timothy Dalton and Vanessa Redgrave in Agatha

5. Agatha, dir. Michael Apted, 1979

This English-to-the-teeth period drama about the real-life disappearance of Agatha Christie is what we might call “speculative biography.” In December 1926, not long after her cad husband (Timothy Dalton) asks for a divorce, Christie, still only a minor celebrity with six published novels under her belt, goes missing for 11 days after getting involved in a minor car accident. To this day the details of her vanishing have never been fully revealed, and the only explanation provided by the author was temporary amnesia. But the mystery of the missing mystery writer became a national obsession and turned the budding novelist into tabloid fodder. Michael Apted’s moody town-and-country set piece, starring a frightened, lovelorn bird of a lead in Vanessa Redgrave, takes a stab at answering the enigma. As the police drag the pond for a body and the press rabidly searches for answers, Agatha flees in a train to Harrogate and checks into a luxury hotel using the last name of her husband’s mistress. Soon, an American columnist (Dustin Hoffman) is hot on her trail, posing as a potential love interest. Agatha Christie is the best-selling fiction author of the modern era and indisputably one of the most famous, yet the fascinating part of the film is watching Redgrave play her as a blur of a character, little more than a fashionably dressed question mark. Is she experiencing a nervous breakdown? Is she purposely covering her tracks and making a game of the deception? Is she trying to throw the suspicion of her vanishing on her adulterous husband? (The third possibility serves as an early blueprint for Gone Girl.) Biopics usually perpetuate the myth that we can know our luminaries inside and out. Apted’s stark film reminds us that we don’t and we never will.

Jason Segel and Jesse Eisenberg in The End of the Tour

6. The End of the Tour, James Ponsoldt, 2015

For anyone coming of age in the 1990s, there was no bigger writer than David Foster Wallace. No self-respecting dorm room was complete without a copy of Infinite Jest, the satirical thousand-page tome that made its author the uncontested voice of a generation. When Wallace hung himself in 2008, shock waves resonated beyond the literary world. James Ponsoldt’s unconventional road-trip biopic begins with news of the suicide reaching writer David Lipsky (Jesse Eisenberg), who’d once profiled the prodigy in Rolling Stone. The film immediately flashes back to 1996, when Lipsky lands the plum assignment of following Wallace on the final leg of his book tour. Viewers hoping for a glamorous peek at literary fame will be grossly disappointed. Jason Segel plays the curmudgeonly, passive-aggressive, press-averse Wallace sporting his signature bandana over long unkempt hair. He’s resistant to the intrusive Lipsky from the minute they meet in the driveway of the novelist’s disheveled ranch house in small-town Illinois, where he’s hiding from the world and teaching a college writing class. (In the classroom scene, an earnest student announces, “I just want my narrator to be funny and smart”; Wallace’s response: “Here’s a tip then. Have him say funny, smart things some of the time.”) Soon the two men, interviewer and subject, hunter and prey, are taking cars and planes to make it to a reading in Minneapolis. Ponsoldt has created a “conversation film,” where plot and character development are found primarily in the fraught exchanges between the reluctant literary genius and a frustrated writer wishing he could be a star. Little happens. The not-quite-friends attend a radio interview, catch an action film at the Mall of America, and eat more than the recommended daily intake of fast food. Meanwhile, their constant banter ranges from a hypothetical date with Alanis Morissette to the sinkhole of mass entertainment to Wallace’s fear of becoming a parody of himself. Ponsoldt brilliantly uses the unrelenting background of the Midwestern winter, full of snow and suburbia, to emphasize the looming sense of isolation. Wallace was a prophet of slacker mass-market capitalism, warning of culture’s ability to seduce the participant “off of any meaningful path.” This film is not a seduction. It’s an unvarnished, unromantic, and occasionally unflattering portrait of the contemporary novelist who is caught between the desire to write about the world and wanting more than anything to withdraw from it.

.jpg)

James Franco in Howl

7. Howl, dirs. Rob Epstein & Jeffrey Friedman, 2010

The Beats are arguably the most mythologized literary Brat Pack in American literature. A slew of films have attempted to capture their brash, bohemian spirit, from the 1980 film Heart Beat, which explores the Cassady-Kerouac love triangle, to the 2013 thriller Kill Your Darlings, about a murder that occurred during their preparatory years at Columbia University. The ambitious, experimental film Howl is a rich soup of genres: part documentary, part biopic about the formative experiences of a young Allen Ginsberg (James Franco) as he discovers himself as a poet, and part courtroom drama focused on the famous 1957 obscenity trial over Ginsberg’s landmark poem, “Howl.” Flashing between historical footage, a reenactment of the witnesses testimony on the definition of moral and literary integrity, and Franco’s rendition of the chain-smoking, bespectacled visionary recounting his awakening, the film aims to capture the radicalism and raw exuberance of Ginsberg and his roving band of “angelheaded hipsters.” “There is no Beat generation,” the young Ginsberg declares at one point in the film. “It’s just a bunch of guys trying to get published.” And yet Howl makes the case that these wannabe writers were true revolutionaries, specifically in regard to the taboo of homosexuality. Despite the limited plot and scant action, Rob Epstein and Jeffrey Friedman have not only managed the rare feat of sneaking literary theory into a feature, but over its length, Franco recites the entirety of “Howl,” all 112 lines. What other film can brag such fidelity to the original material? Ultimately, Howl feels more vital today than it did when it was released a decade and a half ago. That a piece of literature could be deemed so morally destructive that it needs to be censored no longer seems an absurdity of the past.

Ken Ogata in Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters

8. Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters, dir. Paul Schrader, 1985

Yukio Mishima was one of Japan’s most prominent postwar writers, his personal and public life as tumultuous as one of his many novels that bridge Buddhist teachings with the newfound decadence of the East and West. Mishima was, by turns, a soldier, a fitness fanatic, a closeted gay man, and a right-wing ideologue committed to reinstalling the emperor to the throne. All that on top of being his country’s premiere literary mind. It’s no wonder that Paul Schrader broke his meta-biopic into distinct chapters. While Mishima’s biography might seem strange fodder for the writer of Taxi Driver and writer-director of American Gigolo, Schrader creates a phantasmatic puzzle box of a film, helped along by a shimmering score by Philip Glass. The four chapters follow Mishima (Ken Ogata) as he moves from young idealist to outspoken insurrectionist, blending together black-and-white distillations from his biography with candy-colored stage-like forays into his most famous literary works. The through line in all the chapters is the dramatic account of his final public act, a 1970 attempted coup d’état that started by taking a general hostage, and ended in the writer committing seppuku. In Schrader’s hands, the film possesses the flow of a dream, one that doesn’t shy away from sadomasochism, misplaced duty, and public desecration. Underneath Mishima’s Hemingwayesque obsession with masculinity, the viewer gets a creeping sense that Mishima is a portrait of a man overcompensating for his vulnerabilities, one who achieved a modicum of prestige as a writer only to discover that he actually wanted to be a king. Mishima declares: “A writer is a voyeur par excellence. I came to detest this position.” It’s a telling confession, and despite the visual and musical feast of the film, it serves as a cautionary tale about a writer’s inability to distinguish reality from fiction.

“Mishima is a portrait of a man overcompensating for his vulnerabilities, one who achieved a modicum of prestige as a writer only to discover that he actually wanted to be a king.”

.jpg)

Nicole Kidman as Virginia Woolf

9. The Hours, dir. Stephen Daldry, 2002

Based on Michael Cunningham’s best-selling novel, The Hours threads together the fraught, introspective period when Virginia Woolf (Nicole Kidman) was working out the story of her novel Mrs. Dalloway with two latter-day examples of women (Julianne Moore and Meryl Streep) who fall under the spell of the book. Much has been made of Kidman’s prosthetic nose to portray the dour British modernist, but it’s really her whole aura, the awkward shrink of her body, the stiff manner of speaking to staff and children alike, and the hurried, nervous energy and occasional eruptions of anger breaking the contemplative surface. The film opens with Woolf’s suicide, walking out into a river with stones in her coat pockets—there’s no more disheartening start to anyone’s story than their willed death. Despite interweaving three stories of depression and loss, Stephen Daldry manages to create a film bursting with life. Woolf is portrayed as the ultimate introspective writer, at odds with everyone and everything around her. She broods over her work while enduring a visit from her Bloomsbury sister, Vanessa Bell (Miranda Richardson), and fighting with her husband, Leonard (Stephen Dillane), about her right to return to the bustle of London, even if it’s bad for her mental health. “Your aunt’s a very lucky woman,” Vanessa tells her daughter on her visit, “because she has two lives. She has the life she’s leading and also the book she’s writing.” Woolf may be the modern archetype of the sensitive, suffering intellectual, and in this regard Daldry isn’t exploring new ground. Rather, it’s the impact of a single literary work over decades that The Hours so sublimely illustrates. The writer dies, but her work never fades.

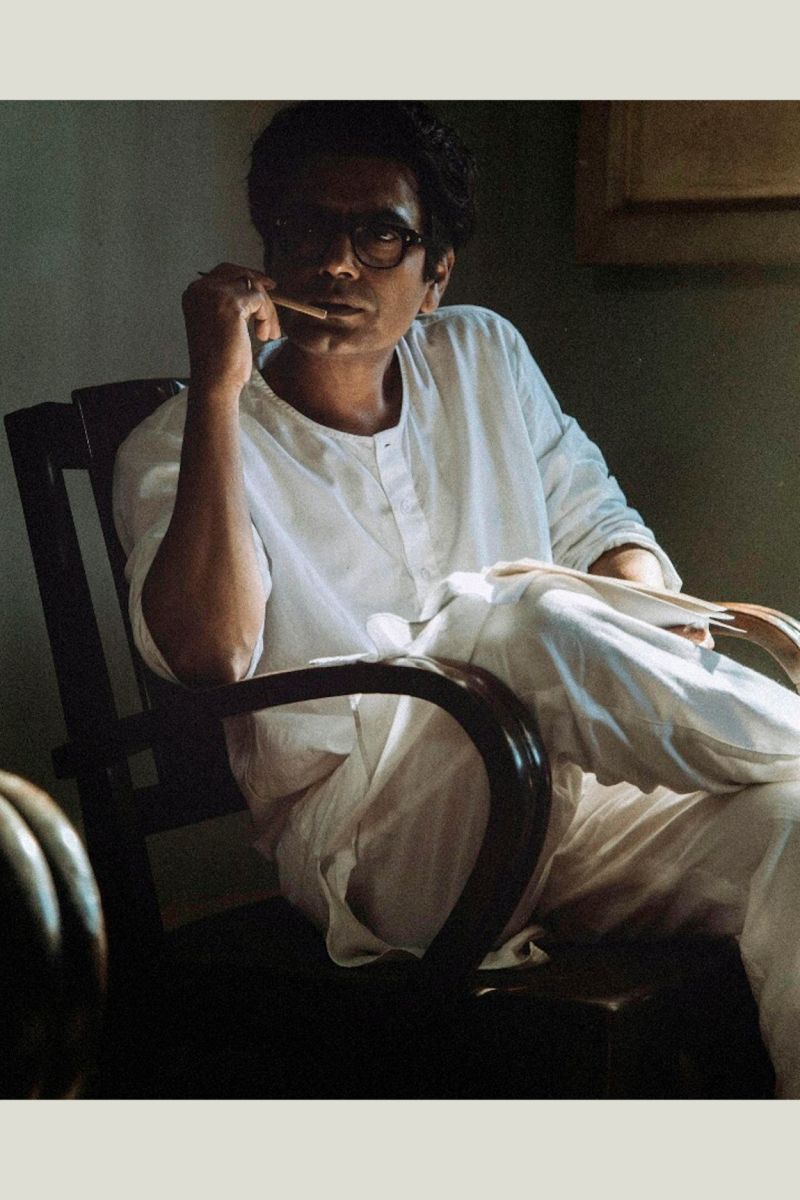

Nawazuddin Siddiqui in Manto

10. Manto, dir. Nandita Das, 2018

“If you find my stories dirty, it is the society you live in that is truly filthy.” Writer Saadat Hasan Manto wasn’t in the business of sugarcoating the truth. His stories weren’t polite and neither was he. In the 1930s he ditched screenwriting in Bombay’s film industry and turned his pen toward prostitutes, refugees and criminals. He was tried six times for obscenity, first in colonial India, then in the newly formed Pakistan. His writing caught the slide from hopeful independence to the bloody rupture of partition. And yet behind that defiant literary voice was a deeply tormented man. He died in 1955, just 42 years old, having produced some of the most powerful short fiction ever written in Urdu. His legacy lives on—or legacies, as it depends on which version of Manto you prefer, based primarily on which side of the partition you live. In Pakistan, Sarmad Sultan Khoosat’s film Manto (2015) is the definitive portrait—a haunting performance by the director himself, spliced with dramatizations of Manto’s most searing tales. But internationally, it’s Nandita Das’s 2018 film that has claimed the spotlight. Simply titled Manto, it’s shot in a pared-down, social-realist style and aligns with India’s cinematic New Wave: gritty, minimalist, focused on the existential malaise of the marginalized. Think Satyajit Ray, but filtered through post-2000s disillusionment. New Wave star Nawazuddin Siddiqui plays Manto with a quiet fury, internalizing the madness of the time, letting it flicker through small gestures and weary silences. His depiction of the writer’s alcoholism is heartbreakingly vivid. Das doesn’t try to reinvent the biopic. By focusing on four crucial years in Manto’s life, the director zeroes in on the man, not just the myth. Ultimately, though, the film can’t help but be a story of the partition—the killings, the betrayals, the fraying of identities—as the British pulled out and left a mess behind. —Kaleem Aftab