We Need to Talk About Mothers and Sons

By Catherine Wheatley

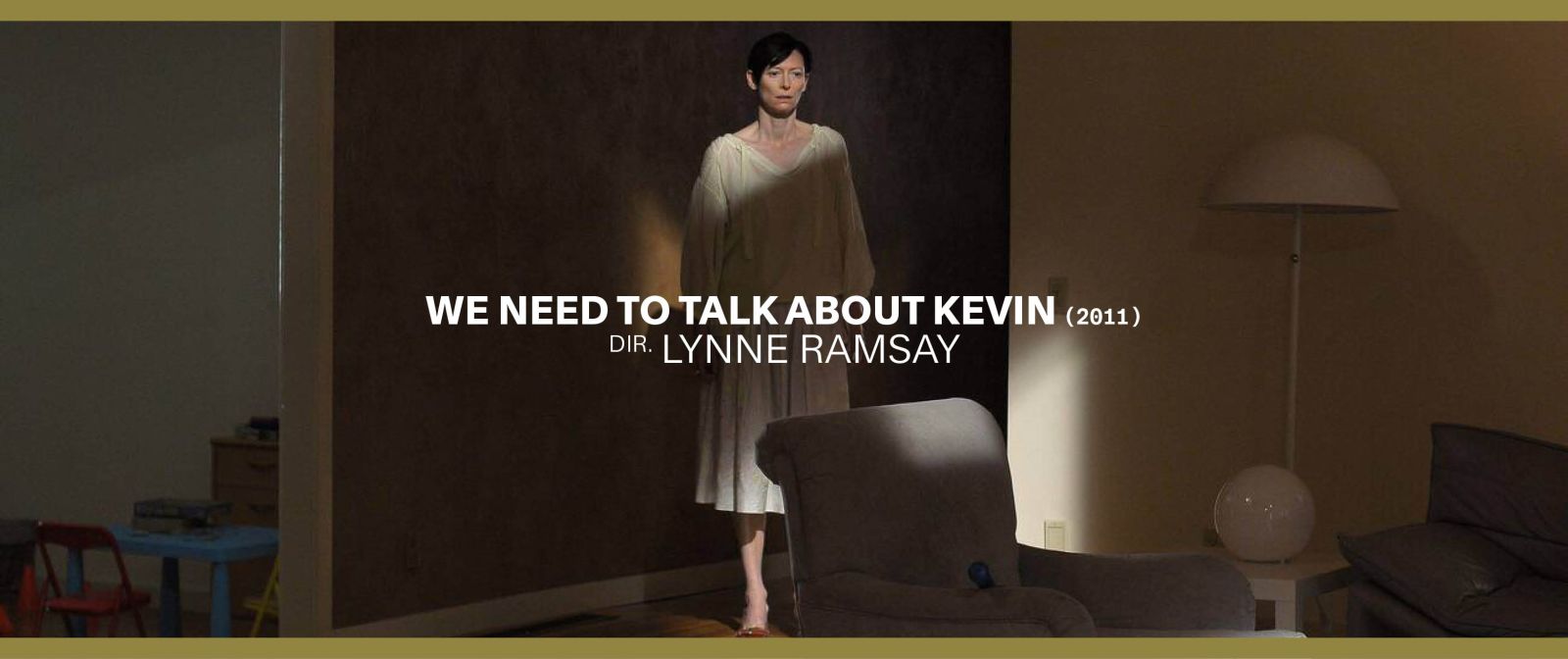

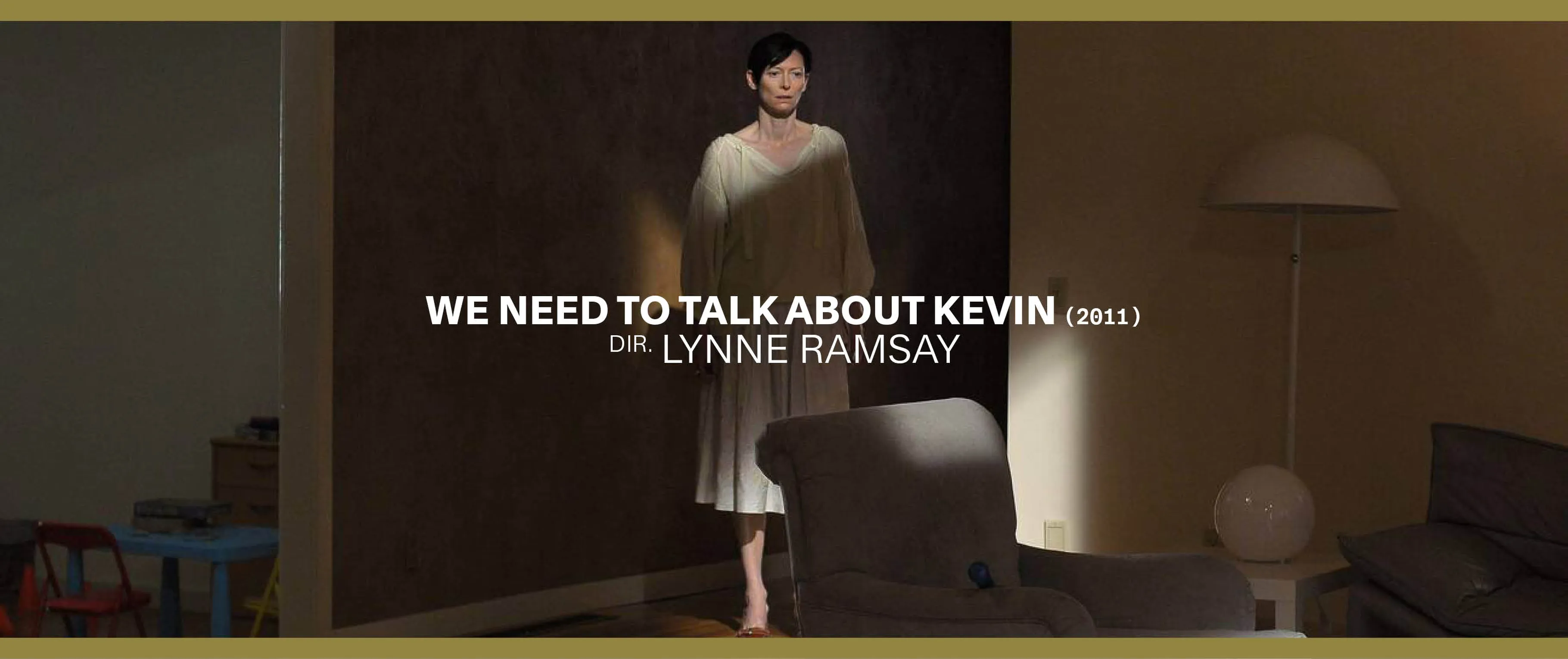

We Need to Talk About Kevin, dir. Lynne Ramsay, 2011

We Need to Talk About Mothers and Sons

At the heart of Lynne Ramsay’s vision of motherhood lies a primal—and relatable—devotion

By Catherine Wheatley

May 10, 2024

I am not scared of my sons. I do not think they will grow up to be serial killers or sadists. They are mostly very ordinary boys, whose knees are scabby and noses snotty and who would, if they could, spend most of their time playing soccer or trading Pokémon cards. They have never, to the best of my knowledge, pulled the wings off a butterfly or taken potshots at a stray cat. My children (whisper it quietly) are nice kids.

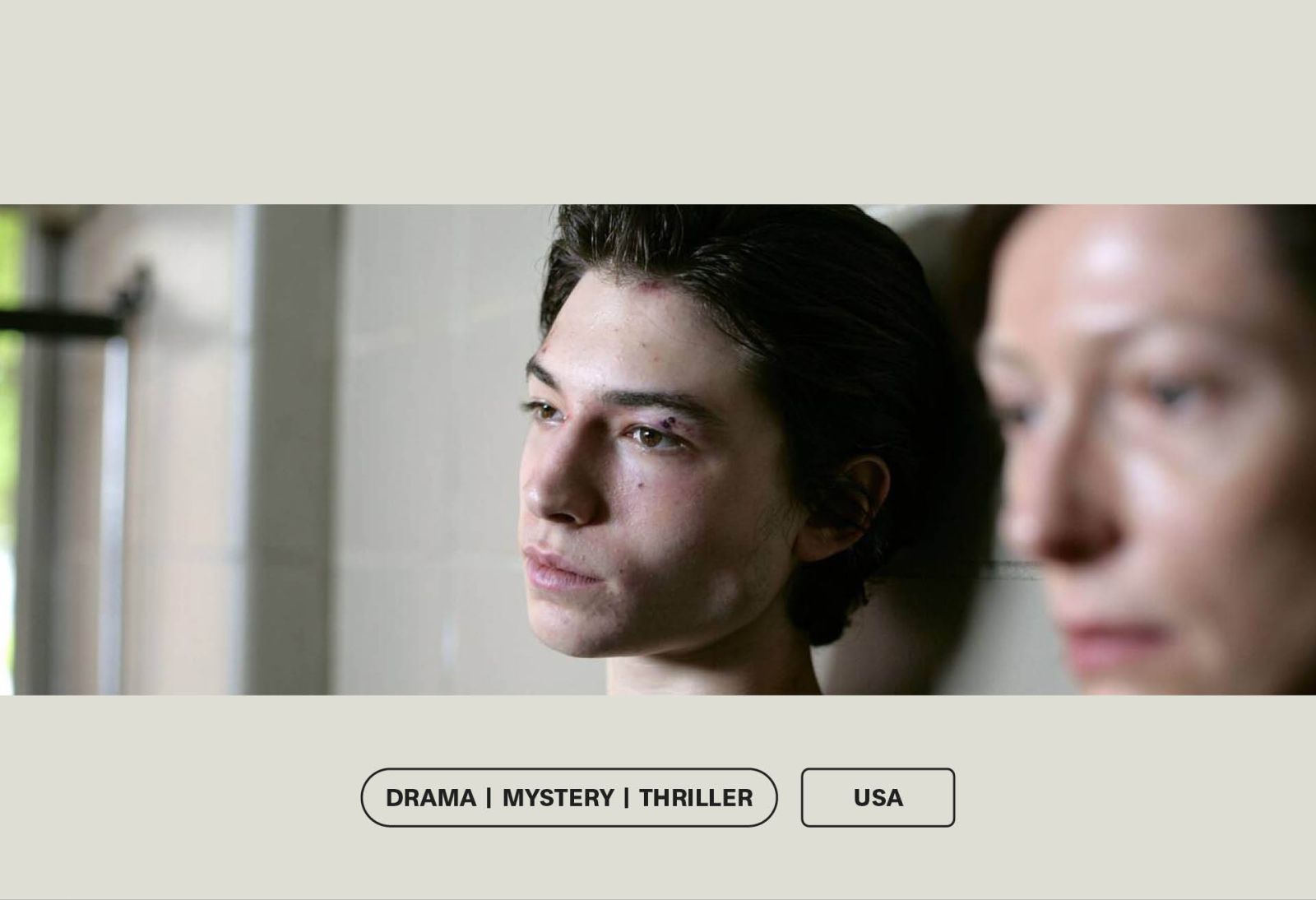

From left: Tilda Swinton and Ezra Miller in We Need to Talk About Kevin

So why is there something about Lynne Ramsay’s We Need to Talk About Kevin—a hallucinogenic nightmare about a child killer who drives his mother to the brink of madness—that feels so familiar? What does my body know so instinctively that I find my hands fluttering to my mouth, my head nodding in recognition as I watch the film’s terrible events unfold? Is it possible that the vicious, antagonistic relationship between Eva Khatchadourian and her son, the eponymous Kevin, is anything like the one I share with my boys?

Both Ramsay’s 2011 film and the 2003 Lionel Shriver book on which it is based have been written about as extreme expressions of maternal ambivalence: the idea that mothers might not always love being mothers, that sometimes they might resent their children and the burden of parenting them. This is not the taboo it once was. As far back as 1947, the pediatrician and psychologist Donald Winnicott explained that there are good reasons for a mother to hate her baby: “The baby is ruthless, treats her as scum, an unpaid servant, a slave.… He is suspicious, refuses her good food, and makes her doubt herself.”

Today there’s a whole genre of maternal self-flagellation memoirs by celebrated authors such as Rachel Cusk, Julie Myerson and Claire Kilroy. (Are you really a hot female author if you haven’t reflected on the endless tedium of diaper changes and playgroups?) Not forgetting the countless horror stories about monstrous and murderous children—films such as Rosemary’s Baby and The Omen, or recent novels by Ashley Audrain and Zoje Stage, which manifest every mother’s deep-held fear that their children might turn against them. It’s in that camp that many critics place Ramsay’s adaptation: The New York Times’ A.O. Scott calls it “a variant on the bad-seed narrative” that weaves “an intense and claustrophobic web of fear”; The Guardian’s Peter Bradshaw describes it as “a nihilist tale of guilt and horror” about “what happens when bad children happen to good parents.”

The film is rather more ambiguous than such descriptions suggest. It’s far from clear that Eva is a good parent or that Kevin is a bad seed. Eva, an ambitious travel writer, is a reluctant mother, begrudging the restrictions that her baby places on her freedom and the demands he places on her time. In the film’s opening images, she is spread-eagled and beatific, bathed in sweet juices and borne aloft, a participant in La Tomatina, the Spanish tomato festival. Pregnant, she regards her growing bump in the mirror with distaste, swathes it in loose-fitting smocks and actively recoils from the yummy mummies coyly stroking their exposed stomachs after prenatal yoga. Foreign objects invade the bohemian New York apartment she shares with her husband, Franklin, the garish primary colors of swing seats and toys crowding out the collection of souvenirs acquired on her travels. Post-child her world is smaller yet, as she is forced to leave the teeming city for life in the sterile suburbs, where she wanders aimlessly through the rooms of the well-appointed home she is initially too exhausted to decorate or traipses around supermarkets selecting food products seemingly at random. Eva, it seems, has lost her appetite, lost herself. While trying to roll a toy ball back and forth with her uncooperative son, she grimaces, and in a singsong voice tells him that “Mommy was happy before little Kevin came along…. Now Mommy wakes up every morning and wishes she was in France!”

From left: Dumbo, supervising dir. Ben Sharpsteen, 1941; The Omen, dir. Richard Donner, 1976

It’s a shocking, unnatural-feeling moment, hearing this mother blame her child to his face for her unhappiness. But I know this feeling, of being a slave to my child and resenting it. I imagine many mothers do. We rarely speak of it, though, for fear of incurring society’s disapproval. The infant Kevin is fractious and needy. As a toddler he won’t speak to Eva; he won’t toilet train until grade school. As a teenager he is terse and withholding. Ultimately, horribly, he will bolt the doors to his high school gym and commit a horrendous, Columbine-style mass murder. Given all that we’ve seen of Eva’s ambivalence toward motherhood, the question poses itself: Is this her fault? Could the atrocity have been averted if only she had loved her son more? The film withholds judgment, but the mothers of many of Kevin’s victims are less forgiving. In the streets, at the supermarket, they hurl abuse and dole out slaps; at home, Eva wakes to find her clapboard house and clapped-out car—symbolic of the sacrifices she’s made for Kevin, having sold the family home to pay his legal fees—drenched in red paint. She accepts these punishments stoically, as if they are her due.

While Shriver’s novel, a book-club favorite, poses the question of Eva’s culpability as an intellectual issue, Ramsay’s film evokes the anxiety of motherhood on a visceral level. I have never felt so animal, so red in tooth and claw as in the weeks after I had given birth. My body leaked and my pulse raced. My hearing was superhuman. No matter how exhausted I was, the slightest noise could jolt me from sleep. In Ramsay’s film vacuum cleaners roar and sandblasters whine; the repetitive sounds of thwacking balls and moaning photocopiers and ticking sprinklers mither at the edges of one’s attention. More alarming is the sudden silence that signals something is terribly amiss. For weeks after my eldest child first started sleeping through the night, muscle memory would wake me at some ungodly hour and I would race to the nursery, craning over the cot until I could hear a faint snatch of breath. When not on high alert, I was strung out and jangly, moving through the world on autopilot. In the six months after my middle son was born, I dropped three separate phones in the toilet.

We imagine early motherhood one way—lazy, lovestruck days spent basking in mutual adoration (think of new mothers in South Korea, who check into postpartum care centers, where they are assisted by a phalanx of helpers)—and it turns out to be entirely different. In Walt Disney’s Dumbo a baby elephant is delivered to his mother by stork, circumventing the sticky oedipal problem so that mother and son can exist in splendid isolation. But when society intrudes on this idyll, in the form of a mean boy who teases and torments her son, the mother’s love is revealed to be so fierce, so all-consuming, that her pupils turn red, her eyes roll in her head and she transforms from a docile, cloth-capped vision of maternal care to a wild beast. As punishment for her loss of control, she is locked away and can only touch her child by reaching through the bars of the cage to cradle him in her trunk.

Ezra Miller as Kevin

“...I know this feeling, of being a slave to my child and resenting it.”

Even as they approach their teenage years, my boys can’t bear to watch Dumbo, because it upsets them too much. I like to think that the problem lies with the idea of being kept apart from their mother, but I wonder if what really bothers them is the vision of maternal rage, of the cloth-capped and docile Mrs. Dumbo’s revelation as a crazed beast. Some days I, too, feel like a mad elephant, and I wish for a sign saying “Danger Keep Out.” Perhaps they sense this and perhaps it scares them: I love them so much it might drive me wild.

I was reminded of Dumbo’s mother-son embrace during an interlude in Ramsay’s film in which Kevin falls ill. Struck down by a vomiting bug, the fight goes out of him; he rejects his father and remains in his mother’s arms as she reads Robin Hood and His Merry Men to him in his bedroom. Eva’s delight at this moment is extraordinary: a huge smile that cracks open her face, perhaps the only time, outside of the opening scenes, she appears happy. I know this feeling too. Whenever one of my children is ill, there is a brief, delicious interlude between the terror and the exasperation when they are sweet and floppy and all they want is me. Like Eva, I cherish these moments, and wish that I could remain in them forever.

For all her protestations, this is what Eva really wants, isn’t it? To keep her boy with her forever. Make no mistake, Kevin is her boy: hers to fuck up and hers to kiss better. The casting of Tilda Swinton and Ezra Miller in the lead roles—two actors who incidentally have fluid relationships to gender—underlines their alikeness. With their beaky noses, beady black eyes, long sinuous figures, their resemblance to each other is uncanny. Facing each other across a table, they appear as mirror images. It’s as if Kevin is the product of parthenogenesis (or as if he’d been delivered by stork).

From left: Mia Farrow in Rosemary's Baby; Harvey Stephens and Lee Remick in The Omen

So what is Kevin’s final, awful act but a manifestation of Eva’s maternal fantasy of unending exclusivity? It’s surely no coincidence that his preparations for the massacre begin immediately after he overhears a conversation between his parents in which they agree to separate. (No need for discussion over who will have custody, because they agree: It’s clear that Kevin will live with his father.) Faced with alienation from his mother, Kevin defers the cutting of the apron strings indefinitely. By dispatching his father and sister, gruesomely skewering them with the bow and arrows Franklin bought him as a gift, he whittles their family to two. Through the spectacular murder of his schoolmates, which occurs off-screen but evokes its mediatization in the slow-motion footage of Kevin emerging from the school doors, arms slightly raised, as the rhythmic blink of the lights on emergency services vehicles segues into the violent, uneven shuttle of camera flashes, he ensures his name will be linked with Eva’s for the rest of their lives and into history, side by side in black-and-white newspaper and Internet accounts of his crime.

Kevin ends the film in prison. Like Mrs. Dumbo he is a danger to society, which must be protected from him. But here, too, he is kept safe, tucked away in a place where Eva can always find him. She is, of course, his only visitor, for who else could possibly love him now? In the film’s final scene, Eva hugs her son, gently rocking him as she holds his scarred head in her hand. As the camera lingers on her fingers clutching his buzz cut, I feel my son’s brushy hair beneath my own. We Need to Talk About Kevin is not a horror film; it’s a love story.