Woman on the Verge

By Deepti Kapoor

Morvern Callar, dir. Lynne Ramsay, 2002

By Deepti Kapoor

May 2, 2025

For some time, Morvern Callar was my favorite film. Picked up in New Delhi in 2006, on pirated DVD from that famous hidden attic shop in the stink-sweat market warren under Connaught Place, it was love at first scene: blinking Christmas lights and a girl lying so intimate beside her boyfriend, who, as the camera pulls out, is dead—killed himself, cold in his own blood on the linoleum floor, with a computer monitor glowing green that says, “Read Me.”

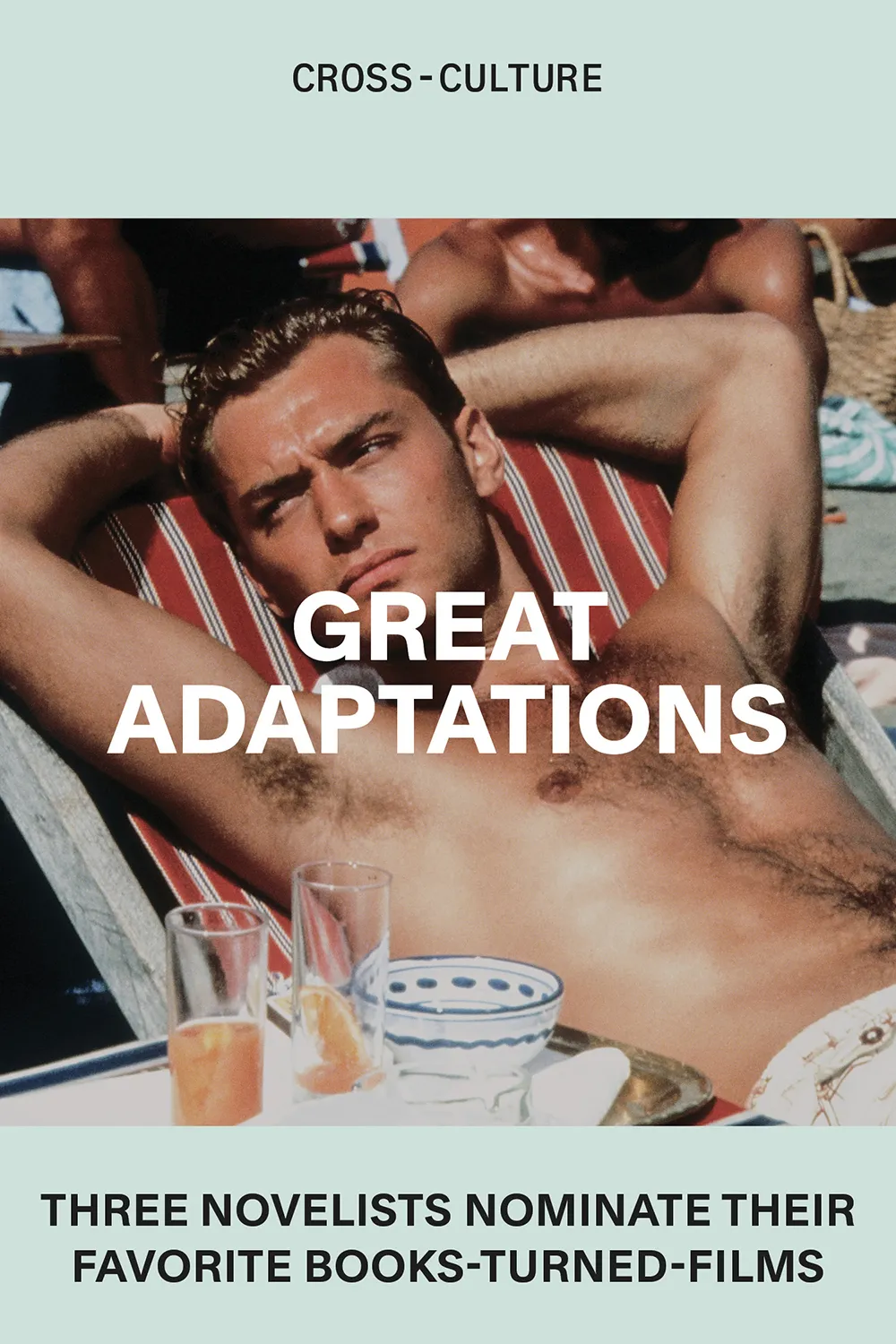

From left: Samantha Morton (center) in Morvern Callar; Lynne Ramsay in 2002

My own boyfriend died not so long before, and I was living, or partying, through it all. Mine fell from a train at sunrise. It might have been an accident, or it may have been a suicide. He made me and broke me in ways that would raise red flags in any era, but he also gave me things I never knew, the gifts of music and sex and drugs, and from his death I took these tools to make myself into someone new. Of course I loved this film. No wonder. In the radical, subversive character of Morvern, left behind with the mess but refusing to play society’s game, I saw a guide, a mentor, a mirror.

Lynne Ramsay’s 2002 adaptation of Alan Warner’s 1995 novel is a marvel of tactile, sensuous cinema. Foremost a character study, an examination of a young woman’s grief and the possibilities that can emerge to fill the vacuum of an evacuated self, the film pointedly refuses to cast moral judgment on its complicated antiheroine (played by Samantha Morton), whose face, body and consciousness fill every frame but whose actions remain mysterious throughout. In his afterword to the novel’s Vintage Classics edition, Warner writes, “If twenty-one-year-old Morvern Callar is anything, then she is an enigma—perhaps even to herself.” Ramsay, meanwhile, has compared her to Camus’s outsider Meursault in The Stranger and, elsewhere, to a female wanderer “like one of those intriguing characters in a Western,” whose sorrow you “don’t get to the bottom of.” Ramsay manages to convey this sorrowful enigma through atmosphere and sound, wielding the camera through intense, lingering close-ups, with an alien and hallucinogenic subjectivity matched by the indelible performance of Morton, in whose minutely intuitive expressions swim quicksilver emotions so astonishing that I struggle to see an actor at all.

Samantha Morton and Kathleen McDermott in Morvern Callar

The plot goes something like this: At Christmas in a port town in Scotland, a young woman discovers that her boyfriend has committed suicide. He has left a note and a novel on his computer. In his note, he asks her to submit this novel to publishers, organize and pay for his funeral with his savings, and be brave. She commits to the bravery. In place of the other two requests, she changes the name on his novel to her own before chopping up his body and burying it on a lonely hill. Submitting the novel to the first publisher on his list, she uses his savings to take off with her best friend on holiday to Spain.

But that’s only half the story, literally and metaphorically. To reduce it to this back-of-the-box précis is to suggest a pacy thriller or, squinting hard enough, a black comedy, a macabre farce. And though in some ways it is both, if the thrill is in psychic flight and the joke is directed at those mighty artistic men, then in the most vital ways the film fits into neither of those easy genres.

How to put it? It is about Morvern, unmoored by grief, unconcerned with the external logic of the world; it is about a woman constrained and used by society, doomed to operate in the marketplace of late capitalism yet armed with eyes and ears and limbs, which she wields to acquire an experiential escape velocity. Sure, at first there are conventional tensions, the simple questions of “What will she do next?” and “Will she get caught?” But these questions are soon absorbed so completely by the luminous, saturated, often psychedelic fabric of the film that they cease to be questions at all. Instead we’re carried into Morvern’s consciousness. By the end of the first half hour, for my money one of the greatest sustained opening sequences in modern cinema, we inhabit an entirely new moral realm.

Half an hour onscreen. Half an hour between discovering her boyfriend’s body and disposing of it. Half an hour before changing the name on the novel from his to her own. In this half hour Morvern decides against calling the authorities, despite walking to a pay phone. Instead, she goes back home and opens her Christmas presents from her dead boyfriend—a leather jacket she wears, a gold lighter she uses, a Walkman with tapes she listens to, the music that becomes the soundtrack to our shared time. She takes a bath; heads out to meet her friend, Lanna; consumes ecstasy; gets drunk in the pub; goes to a rural house-party/rave; gets lost all night in the cold eternal happiness only MDMA can provide; exposes herself like a prostitute to a trawlerman on the coastline; takes another bath, this time with Lanna at the latter’s grandma’s house; and in the morning clocks into work at the local supermarket, a repetitive slave-labor slice of life whose sterility blinds us. She visits Lanna’s grandma again, until finally, finally, she returns home to face the inevitable (even then, she puts a frozen pizza in the oven first).

The inevitable is death. The inevitable is a call to the cops or the ambulance. The inevitable is his suicide note on the screen with his directives for her to take. We follow her eyes. Onscreen, the words I wrote it for you. The oven timer rings out in the silence: a jump scare, an alarm call. She could still call the cops and claim she walked in on him just now. But we are in her moral universe. Tentatively, then firmly, she changes his name on the novel to her own, a decision that takes control of, and dictates, the course of her life.

“The film hasn’t so much pleaded Morvern Callar’s case as thrown it out entirely.”

And when this pivotal moment comes, we barely flinch. We certainly don’t oppose her crimes. We don’t even ask the question: Why? Cinema is an empathy machine, of course, and a bloodletting device for illegal impulses, but there is something more going on here; during the night, the film hasn’t so much pleaded Morvern Callar’s case as thrown it out entirely. The director has committed to screen the thought that the story’s novelist originally posited in granting her act innocence: “Apart from denying an insentient being his literary legacy, does Morvern really do anything so wrong?”

I certainly didn’t think so in 2006. I reveled in her rebellion, in her seizure of destiny and her subsequent flight to Spain, where she begins to untangle the knots of desires, needs, wants; rejects the habitual and the mundane; enters slowly, painfully, sometimes frustratingly, into a near-silent self-awareness and renewal. I saw her act of dismemberment and literary fraud as one and the same, two sides of the same coin, liberation and justice, claiming agency from a man and a world that had caged her like a songbird, denying flight. And when the publishers came calling, chasing her down to Spain with contract in hand, wowed by her genius first novel, I laughed at the coup, I saw the victory she achieved in immortalizing her name.

I still see it like that.

But I see other things, too, crucial factors I missed back then that only deepen the film.

Samantha Morton and Kathleen McDermott in Morvern Callar

In the years after my boyfriend died, after I had partied myself to oblivion and back, I met and married a man who grew up in Northern England, in a region scarred by deindustrialization and the neoliberal policies that so decimated communities like the one portrayed in the film. My husband went to school with people like Morvern and Lanna, like the hedonistic ravers they meet in Spain. And like the dead boyfriend, he was educated outside his class. Unlike the dead boyfriend, he didn’t return home to write a novel. He wandered to India.

Visiting England before and after we were married, I began to understand a little more the textures of these worlds, of lonely, terraced houses with net curtains, of grandmas sitting in easy chairs waiting for doorbells to ring, of the pub as community hall, locus of (in)action and refuge from despair. And I understood what rave culture meant in the late ’80s and ’90s, how its drugs and anarchic ruptures offered the potential to reorganize life, create new forms of being, and how that potential was eventually squandered, as almost all potentials are, to be packaged by the mainstream it stood against and turned into weekend commodities of dead-end hedonism sandwiched between hours of deadening work.

These days I see the film in the context of class relations just as much as private identity—Morvern’s awkwardly naive interactions with the publishers who fly out to meet her in Spain display the gulf between those worlds, while Morvern’s bold exchange with Lanna in the final scenes, in her exhortation to “fuck work,” reveals just how much our heroine has risen above the prison in which she began.

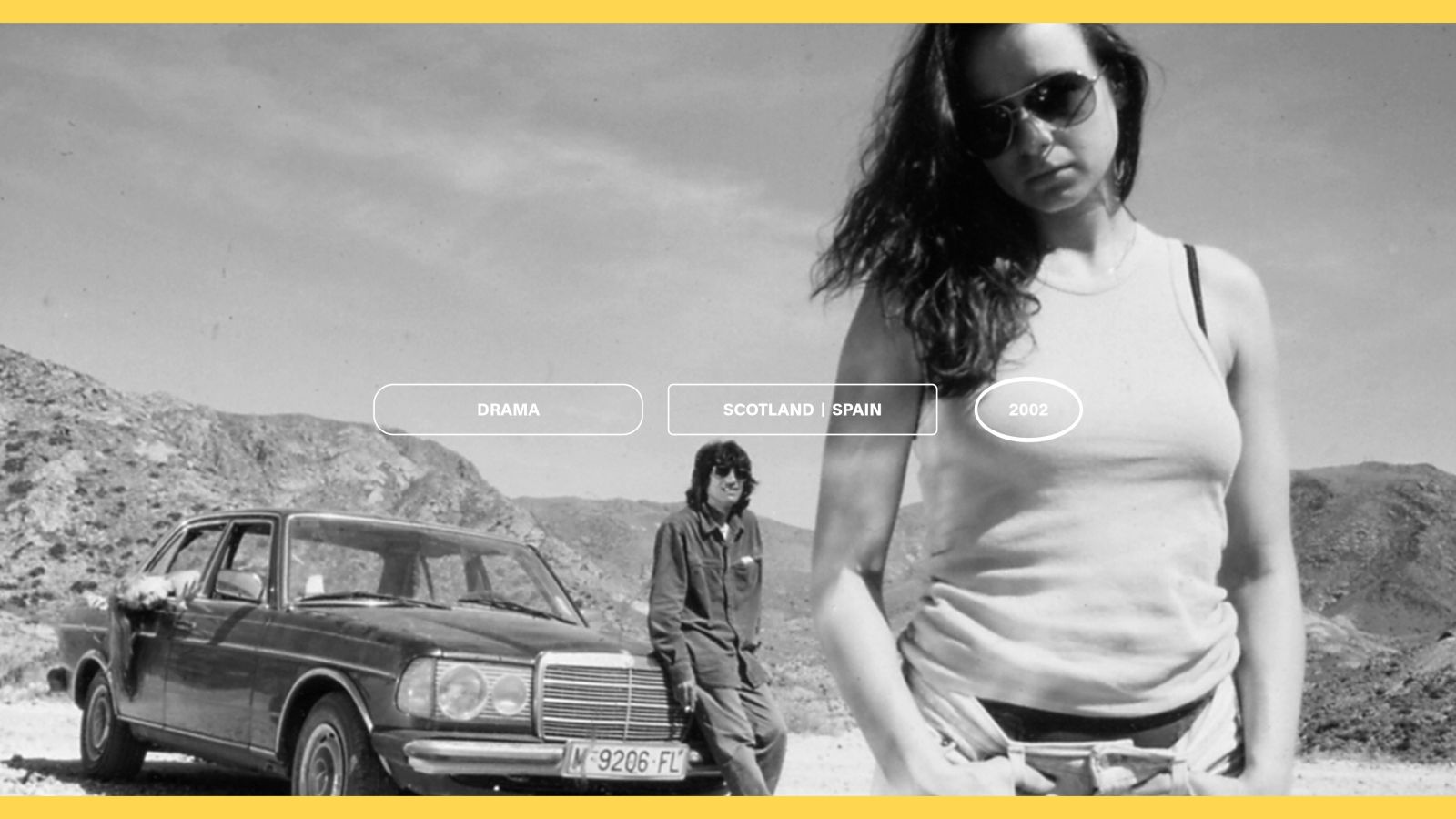

Morvern Callar

And while Morvern will forever remain her own woman, her twin acts of crime and deceit speak for something beyond the strictly personal. It’s not for nothing that her boyfriend’s suicide note in Warner’s novel (not seen in the film) contains the line: “LIVE THE LIFE PEOPLE LIKE ME HAVE DENIED YOU.”

I often wondered, back then, what Morvern Callar would do with her literary fame. I presumed she would shun it, become a ghost (and sell more copies in the process). But now I think I was asking the wrong question. Literary fame is irrelevant: She has extracted the value of her boyfriend’s literary worth, which has, as he stated in his note, exploited people like her. She has reclaimed at the stroke of a keyboard not only her selfhood but her class dignity. “I wrote this for you,” his note said. She takes him at his word, trading in his literary immortality for nothing more and nothing less than cold hard currency, which is the only thing that matters in the end, not as an end in itself but as the means to provide her freedom.