Heightened Tones

By Yonca Talu

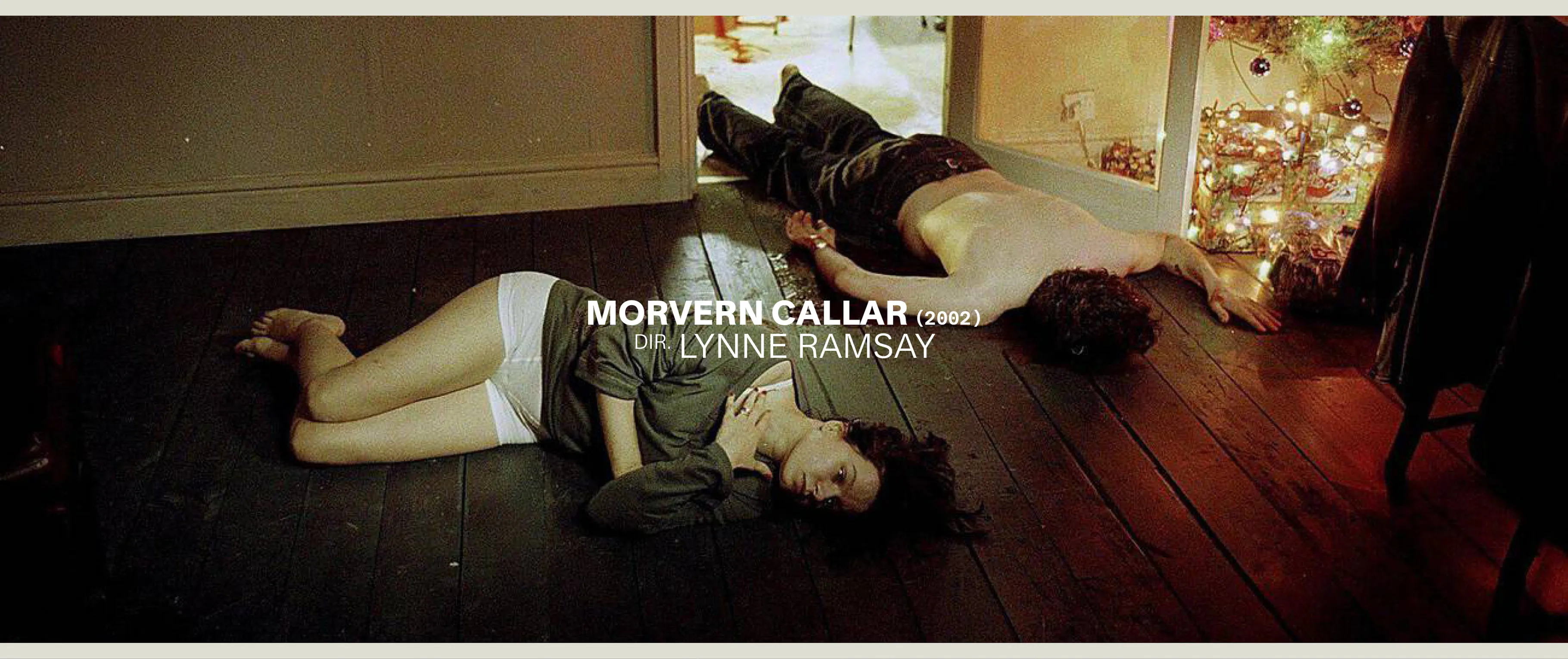

Morvern Callar, dir. Lynne Ramsay, 2002

By Yonca Talu

May 2, 2025

“Lynne is not scared of revealing the mechanics of her films,” says sound designer Paul Davies of the heightened, expressive approach he takes in his long-standing collaboration with director Lynne Ramsay. The two first crossed paths in the mid ’90s, when she was a student and he was a teaching assistant at the UK’s National Film and Television School, and have been working together since the end of that decade. Drawing from his background in experimental and electronic music, Davies excels at sculpting and manipulating sound to plunge the audience into the inner worlds of Ramsay’s vulnerable antiheroes: a boy guilty over his friend’s death in Ratcatcher (1999); a party girl grieving her boyfriend’s suicide in Morvern Callar (2002); a mother grappling with memories of her school-shooter son in We Need to Talk About Kevin (2011); and a hit man suffering from PTSD in You Were Never Really Here (2017). In these narratives of trauma and loss, Davies turns ordinary sounds—squealing train tracks, buzzing lights and ticking sprinklers—into haunting evocations of impending doom. Currently in postproduction on Ramsay’s upcoming feature, Die, My Love, Davies spoke with Galerie about the evolution of his partnership with the director and brought their work into conversation with two other highlights of his filmography: Steve McQueen’s IRA drama Hunger (2008) and rising filmmaker Rose Glass’s psychological horror debut, Saint Maud (2019).

From left: Kathleen McDermott and Samantha Morton in Morvern Callar; Ratcatcher, dir. Lynne Ramsay, 1999

How did you approach the sound design of Lynne Ramsay’s first feature, Ratcatcher, which stands apart as her most naturalistic film?

Ratcatcher was an interesting challenge for me. I had previously worked on films in which I could be sort of expressionistic with sound design, like John Maybury’s Love Is the Devil: Study for a Portrait of Francis Bacon [1998] and Julien Temple’s Vigo [1998]. But when I saw Ratcatcher, I realized that I had to take a more naturalistic approach to it.

There’s still a dash of expressionism in Ratcatcher’s soundtrack, as exemplified by your stylized use of rail squeals in the film’s opening scenes.

Yes. There’s no score in the film’s opening eight minutes, so the sound design had to subtly express the drama of the boy’s drowning in the canal. But it also had to seem like it could naturally belong to the environment in which the film is set [i.e., a 1970s Glasgow tenement block]. Hence, my use of certain sounds, like industrial sounds, distant rail yard sounds and kids’ voices—which I recorded around our postproduction studio, in London—as compositional elements.

A key inspiration for Ratcatcher was the cinema of Robert Bresson, which, interestingly, was also a major influence on another film you sound-designed, Steve McQueen’s Hunger. Did you tackle those films in a similar way?

I did. I remember doing an initial pass of Hunger and using prison-movie tropes, like distant door slams and key jangles. But Steve listened to that and said, ‘‘I don’t want any of these tropes. This isn’t a prison movie. The reference is Bresson’s A Man Escaped [1956].’’ Back then I hadn’t seen A Man Escaped, which wasn’t readily available on DVD in the UK. But I’d seen other Bresson films and had emulated his minimalist, selective approach to sound design in Ratcatcher. So I knew what Steve meant.

There’s also a sense of minimalism and selectivity in the soundtrack of Lynne Ramsay’s second feature, Morvern Callar. I’m thinking especially of the film’s virtually silent opening sequence, which is punctuated by the buzz of flickering Christmas tree lights.

Yes. It’s quite difficult to work in that bare, Bressonian way because each sound has to be right. You can’t hide a lot of sounds under different layers and get away with it. Initially, my sound design for the opening sequence of Morvern Callar was much more elaborate. I’m very influenced by the work of David Lynch and his sound designer Alan Splet [whose collaborations include Eraserhead, 1977, and Blue Velvet, 1986]. So my natural inclination was to go down a similar route on Morvern Callar. But Lynne listened to the first version of the opening sequence and graciously said, ‘‘This is great, but it’s not what I’m looking for. I want something much more simple in the background, just a sort of hum.’’ We were working in my editing suite, and she turned around and said, ‘‘That’s the sound!’’ She was referring to the fans on the back of my computer. So I recorded that sound and used it as a backdrop for the buzz, which yielded a very uncomfortable opening sequence. It’s so stark that it forces the audience to listen.

Another technique through which Morvern Callar arrests the audience is the use of heightened Foley.

That was also inspired by Bresson. Lynne described heightened Foley as the audio equivalent of a visual zoom and a way of drawing the audience in. Seeing the characters in a wide shot but hearing their footsteps and movements as if they were up close makes us form a connection with them.

The film is sprinkled with scenes of Morvern [Samantha Morton] listening to an eclectic mixtape her boyfriend made her before committing suicide. How involved were you in the selection of those songs?

At the end of Ratcatcher’s postproduction, Lynne mentioned that her next film was going to be an adaptation of [Alan Warner’s 1995 novel] Morvern Callar. She suggested that I read the book, which I did. It featured a whole list of music, which she wasn’t at all familiar with. But I was. It was my ear: German rock and British new wave. So I compiled a CD for her as a listening reference. Some tracks on there, like Can’s ‘‘I Want More’’ and Holger Czukay’s ‘‘Cool in the Pool,’’ ended up on Morvern’s mixtape. Other songs on the mixtape, like the ’60s hits ‘‘Some Velvet Morning’’ and ‘‘Dedicated to the One I Love,’’ were selected by Lynne herself. Music supervisor Andrew Cannon also provided his own selections.

The songs on the mixtape alternately play out as a nondiegetic score and diegetic music emanating from Morvern’s earphones. This creates the unsettling feeling of slipping into and out of the character’s consciousness. How did you come up with that effect?

That was Lynne’s idea. She was very clear about how she wanted the songs to fade in and out of nondiegetic and diegetic. She and the editor, Lucia Zucchetti, mapped out those transitions in the picture edit. Then they were polished in the sound design and mix by myself and rerecording mixer Tim Alban. The mixing of the music plays a big part in the film’s expressionism. In the late ’90s, Lynne’s short films and Ratcatcher led her to be bracketed with British social realism. But Morvern Callar changed that perception and established her as a singular voice in British cinema. This being her second feature, Lynne was also more aware of what she could achieve with sound and was thrilled to experiment with it.

Lynne Ramsay’s following feature, We Need to Talk About Kevin, fully embraces an experimental style. How did you two devise that film’s sound aesthetic?

Lynne brought me on board We Need to Talk About Kevin much earlier than usual, during director’s cut. When I saw the edit, I said to her, ‘‘We can really push this film’s sound design.’’ It was clear that this was a different beast from her previous work. She even described it as a horror film, hence, the prominence of red in the visuals. I felt like the sound design could also use genre tropes and lean into a Lynchian kind of aesthetic. So I started experimenting with electronic sounds, like drones, which were incorporated into the picture edit. Later, when Jonny Greenwood became attached to the film as a composer, he provided various cues, which blended well with my approach. There are a few moments in We Need to Talk About Kevin when the sound design actually gets interwoven with the score, which I think contributes to the film’s seamlessness.

The musicality of your sound design is particularly palpable in the film’s eerie opening sequence, in which you build the beat of lawn sprinklers to a crescendo over a tracking shot of billowing curtains. How did you and Lynne Ramsay settle on that opening sound, which foreshadows the film’s chilling finale?

The film originally started with a beeping digital alarm clock. It was only later in the postproduction process that Lynne decided to open it with the curtains and sprinklers, though I suspect she’d always had that idea in the back of her mind. The sound of the sprinklers is probably the most talked about sound effect I’ve ever used, but it comes from a standard sound-effects library. I just cut together several tracks of that sound. In fact, it was initially a placeholder for an original recording, but it worked so well that it remained in the film.

“She turned around and said, ‘That’s the sound!’ She was referring to the fans on the back of my computer.”

There’s a kinship between the opening sequences of We Need to Talk About Kevin and David Lynch’s Blue Velvet.

I hadn’t thought of that, but you’re right. It must have been an unconscious reference. Both of those opening sequences are about what lies underneath the surface, and the sprinklers in We Need to Talk About Kevin do sound like the demonic insects in Blue Velvet.

Throughout the film, you emphasize Kevin’s diabolical quality by amplifying his sound effects, like when he throws his backpack on the kitchen counter and removes chewed-up fingernails from his mouth.

Yes, also when he eats lychees. I remember Lynne and I discussed the loudness of those sound effects, wondering, ‘‘Have we gone too far?’’ We were concerned that the mix might feel too unnatural and call attention to itself. That’s something you’re advised against in film school. But Lynne is not scared of revealing the mechanics of her films.

The film is a memory piece that operates by association, with images and sounds that echo and respond to each other: an ultrasound and a printer; a crying baby and a jackhammer; hands tapping on a window and eggs smashing on a fridge.

Yes, those links drive the film’s editing and sound design. It obviously helped that I collaborated so closely with the editor, Joe Bini. We passed our work back and forth, which allowed us to feed off each other. Lynne also spent a lot more time with me in the sound-editing suite. When I saw the finished film, I was very pleased with the fact that the picture, sound and music were all working toward the same goal. In that respect, We Need to Talk About Kevin is the most unified, organic and fluid film I’ve ever done.

Like We Need to Talk About Kevin, You Were Never Really Here delves into the psyche of a traumatized character. In interviews, Lynne Ramsay has compared protagonist Joe’s thoughts to shards of glass. Did she also bring up that image to you?

She did. Her exact phrase was ‘‘Joe [Joaquin Phoenix] is a guy who walks through New York with a head full of broken glass.’’ That gave me an understanding of the character, who feels detached from his environment. His only emotional connection is with his mother. Hence, the contrast between the quietness of his mother’s house, which is his safe space, and the loudness of New York. The rerecording mixer, Andrew Stirk, said that You Were Never Really Here should be a film with square edges. That meant exaggerating, rather than disguising, the sound cuts. So when Joe steps out of his mother’s house and into the city, he’s greeted by an overwhelming burst of sound.

From left: We Need to Talk About Kevin, dir. Lynne Ramsay, 2011; You Were Never Really Here, dir. Lynne Ramsay, 2017; Saint Maud, dir. Rose Glass, 2019

I used to live in New York and rewatching this film definitely made me reexperience that city’s sonic overload.

That’s good because I’ve never been to New York!

Oh! So how did you go about designing its soundscape?

I relied a lot on sound mixer Drew Kunin’s production sound. My assistant sound editor, Morgan Muse, who’s American, also went to New York and made street recordings, which were used in the film.

Were you influenced by any films set in New York?

No. But I was influenced by an installation filmed in New York: American artist Charles Atlas’s Joints 4tet Ensemble [1971–2010], which I saw at Tate Modern in London. It consisted of multiple screens and four foreground speakers, each of which played a different sound of the city. I thought that was an interesting idea, and I incorporated it into You Were Never Really Here. There are several instances in the film where a different city sound comes out of each surround speaker, which creates a sense of fragmentation. But it’s done in a way that the audience can’t put their finger on. They just feel uncomfortable, like something isn’t quite right.

Like in Ratcatcher, train sounds are an important motif in You Were Never Really Here.

Yes. There’s a sequence toward the end of the film where Joe rides a train and has visions of the girl he rescues. The close-up on Joaquin’s face was shot in a single 11-minute take with sync sound. At some point in the production sound, there was a rail harmonic. Lynne identified that and said, ‘‘This is the sound I want to use as a motif throughout the film.’’ So I isolated, stretched and manipulated that sound, and I used it whenever we went inside Joe’s head, including in the train journey.

From left: Hunger, dir. Steve McQueen, 2008; Samantha Morton in Morvern Callar

You also bring us inside Joe’s head by intensifying his breaths.

That was informed by my work on Hunger. On that film, I used breaths as a dramatic device to get the audience to identify with the protagonist, Bobby Sands, played by Michael Fassbender. Michael and I spent a long time in the ADR booth recording his breaths, which I treated almost like dialogue. I did the same with Joaquin’s breaths in You Were Never Really Here.

Since 2019, you’ve been collaborating with Rose Glass, whose two features, the psychological horror film Saint Maud and the pulp thriller Love Lies Bleeding [2024], also use sound in a subjective way. Did she seek you out because of your work with Lynne Ramsay?

Yes. You Were Never Really Here was actually one of her references for Saint Maud.

So did you draw on what you’d done there?

I did. I made the house of Maud’s patient, Amanda [Jennifer Ehle], sound a bit like Joe’s mother’s house in You Were Never Really Here: quiet, with minimal ambiences and heightened Foley. I also contrasted the house with the outside world: the [northeast English] seaside town of Scarborough, with its amusement arcades, burger joints and pubs. Finally, to depict Maud’s headspace, I jumped to the other end of the scale and used a lot of drones and electronic processing.

What was it like to work with Rose Glass?

Saint Maud was quite a low-budget film, and Rose and I didn’t have a lot of time to develop our approach to the sound design. But she came to see me pretty much every day and we went through the film together, which is also how I’m used to working with Lynne. Both Lynne and Rose have a very clear vision, but they also leave a lot of space for other inputs and ideas. They encourage their collaborators to think outside the box and take risks, which to me is the mark of a good director.