Éric Rohmer's Final Act

By Rebecca Voight

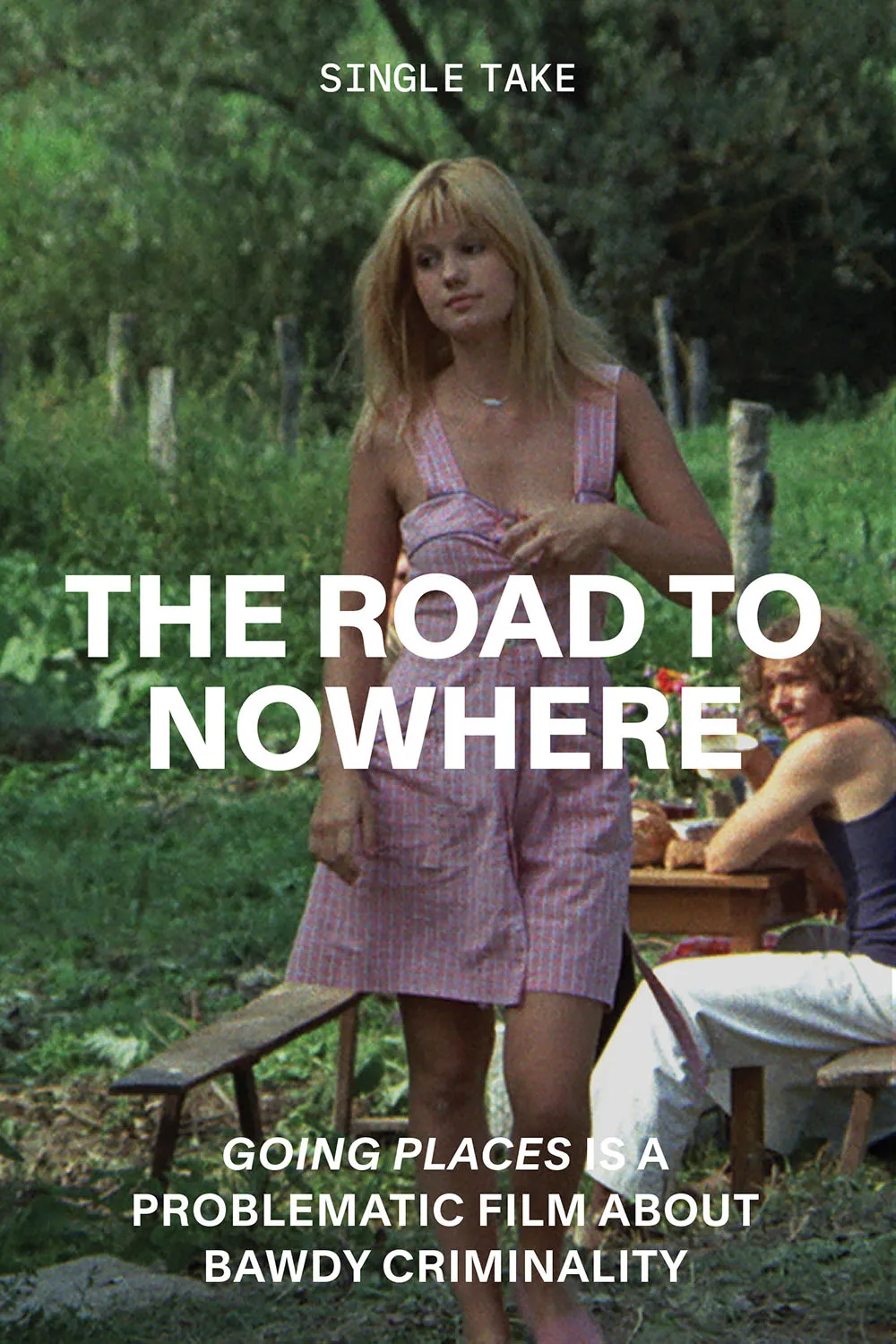

The Romance of Astrea and Celadon, dir. Éric Rohmer, 2007

Éric Rohmer’s Final Act

More than a decade after the French New Wave director’s death, his creative legacy endures in an unproduced screenplay

By Rebecca Voight

December 20, 2024

When Éric Rohmer, the father of France’s Nouvelle Vague film movement, died at age 89 in January 2010, there were the requisite homages but surprisingly little fanfare. In contrast, when Johnny Hallyday, France’s self-styled Elvis, died in late 2017, he received a royal send-off, escorted by a procession of 700 bikers down the Champs-Élysées to a service at Paris’s La Madeleine church attended by three French presidents. But the Nouvelle Vague, one of the most transcendent movements in film, was largely overlooked in France by the time of Rohmer’s passing, its protagonists criticized as 1960s navel-gazers. Little did the public know, the director was not quite finished with his cinematic legacy—he’d made plans for one final film to be shot after his death.

![]()

Éric Rohmer

![]()

Éric Rohmer and Andy Gillet on set (photo by Françoise Etchegaray)

Rohmer himself was a late bloomer. Before he turned to directing, he worked in Paris as a film critic, eventually serving as editor in chief of the influential Cahiers du Cinéma journal, where he cultivated a circle of young critics, devotees and friends: François Truffaut, Jean-Luc Godard, Claude Chabrol and Jacques Rivette among them. Together they argued for more relaxed filmmaking in tune with the liberated times, but what they all really wanted was complete creative freedom. As pioneering directors, they soon got it.

Even then Rohmer was slow to the table. He’d been writing and directing little-noticed films for a decade before his breakout black-and-white morality tale My Night at Maud’s caused a sensation at the 1969 New York Film Festival. François Truffaut’s The 400 Blows and Jean-Luc Godard’s Breathless had gained instant recognition 10 years earlier; by the time of Rohmer’s debut, the Nouvelle Vague, a school of art-house filmmaking calling for an about-face from film’s formal narrative and craft, had already reached its zenith. But Rohmer, one of its founding members, had only just emerged from obscurity. Over the next four decades, he would invariably do things his way.

Watching a Rohmer film can feel a bit like following a grown-up dinner-table conversation as a child. One tunes in and out, catching an interesting bit here and there while daydreaming about dessert, observing a cat quietly passing through the room or wondering what’s going on just outside the window. The viewer’s wavering attention is just what Rohmer was after, as he allowed his intricate tales of love and sex to meander in a subdued, natural way before zeroing in on a climactic moment. That’s what happens in 1970’s Claire’s Knee, when an older career diplomat, Jérôme, experiences his erotic epiphany as he contemplates the spectacle of teenage Claire (and her legendary knee) perched on a ladder on a hot July day on Lake Annecy, at the base of the French Alps.

My Night at Maud’s, dir. Éric Rohmer, 1969

When I first arrived in Paris from the U.S. in 1981, Rohmer was the start of my French education. He had mastered a form of laconic storytelling that was about as far away as possible from the riveting action of Hollywood films. In Rohmer’s films, little appears to happen. The actors hardly register emotion. The tales unfold in extended narrations, introspective monologues and thought-provoking exchanges drawn out over long takes. For me, life in France was like that. So much was going on, while on the surface there was barely a ripple. Establishing a production company in 1962 with Barbet Schroeder allowed Rohmer such freedoms, and he stuck to a recipe of filmmaking he’d keep for the rest of his life: discovering new actors rather than depending on big names, working with natural light, and choosing existing surroundings rather than constructing sets.

Producer Françoise Etchegaray had worked for Jean-Luc Godard before she found herself alongside Rohmer in Biarritz in 1984 for his film Le rayon vert (The Green Ray). The film is inspired by Jules Verne’s 1882 story of the same name, about a young heiress searching in Scotland for the green ray, a light on the horizon seen only on rare occasions that permits those who view it to see clearly into their own and each other’s hearts. The film version follows a woman as she drifts from one vacation spot to the next; she overhears a tourist describe the phenomenon, which she will see when she eventually finds love.

The filming proved to be a quick course in Rohmerian improv for Etchegaray. At 64, Rohmer yearned to lighten up, to recapture the Nouvelle Vague spirit of his start. The actors worked for scale (paid by the director in cash that he kept in a plastic bag) and wore their own clothes, and some of the scenes were shot in their actual homes. “The crew included just three people,” Etchegaray recalls. “One girl on images, another on sound, and me. That was it. And there was no script. The only thing Éric asked me before we began was ‘Have you read Le rayon vert by Jules Verne?’”

A painter friend of Etchegaray’s found someone to put up the crew and cook for them in nearby Cambo-les-Bains. Two of the women working behind the scenes had cars, which they used to ferry everyone around. And Rohmer himself, vacationing in Biarritz with his wife at his in-laws’ beachfront apartment, didn’t even tell his family he was making a film. He’d always been secretive and tended to compartmentalize his life. He had changed his name from Maurice Schérer to Éric Rohmer when he began directing films so that his mother would never know what he was doing. Even his close collaborators did not meet his family until after his death.

Éric Rohmer (photo by Françoise Etchegaray)

When a police officer didn’t want the crew’s cars in a casino parking lot near the beach where they were filming, Etchegaray convinced him to bend the rules by telling him they were just three poor students with their cranky professor doing a school project. “I never expected the film to come out, because it was shot on 16mm film. When it did come out two years later, it won the Golden Lion in Venice and sold to 60 countries,” she remembers. It was such a success that there are still places around Biarritz called Le Rayon Vert.

Over the next two and a half decades, Etchegaray worked with Rohmer on 11 features and several short films. As producer, she did everything from casting and research to driving and cooking. “It all seemed very spontaneous, but behind that was planning,” she says. “Rohmer never started anything without knowing where he was going. His stories may appear casual, but he had the ending in mind before he began.”’

By the 1980s, the sense of unity that had bonded the directors of the Nouvelle Vague had eroded. “Rohmer liked Claude Chabrol,” Etchegaray notes, “but he didn’t like all his films. Once he asked me to propose a meeting with Jean-Luc Godard, who told me he had nothing to say to a bourgeois filmmaker. The only one Rohmer remained close to was François Truffaut, who helped him financially on several films, including Le beau mariage [A Good Marriage, 1982] after [production company] Gaumont dropped out at the last minute.” One day, just after completing Le rayon vert, Etchegaray and Rohmer were walking down avenue Pierre 1er de Serbie in the sixteenth arrondissement, where he and Truffaut both had offices. They ran into Truffaut, and Rohmer asked him how he was. “That was in September,” says Etchegaray. “Truffaut told us he was doing terribly, that he had a brain tumor and was going to die. A month later he did.”

Just as Rohmer had drawn avant-garde critics and filmmakers around him in his days at Cahiers du Cinéma, in the 1980s he attracted younger creatives in his office to talk about art, film and life. He launched the acting careers of Fabrice Luchini, Arielle Dombasle, Melvil Poupaud and Pascal Greggory, all major stars in France today. He often taped them, and their conversations inspired the dialogue and scenarios for his projects. “In Rohmer’s films,” said Greggory in a 2006 interview, “an actor has nothing more to do than to be himself. Sometimes this is a little bit dangerous for an actor, but at the same time it’s wonderful because it’s a collective adventure that gives us the impression to contribute to the cinema experience.”

![]()

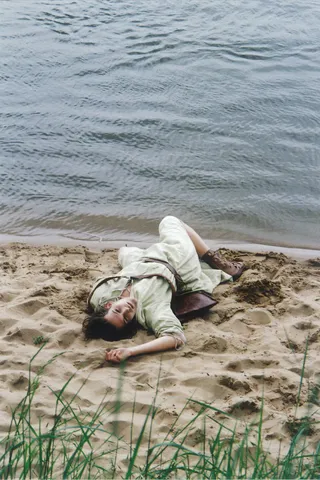

Andy Gillet as Celadon (photo by Françoise Etchegaray)

![]()

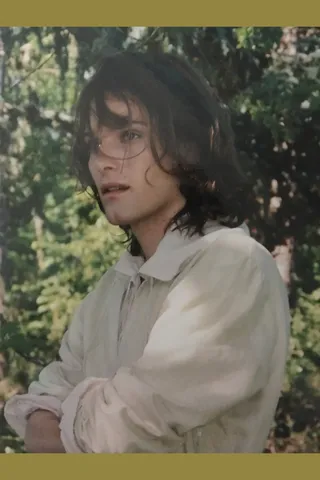

Andy Gillet (photo by Françoise Etchegaray)

Haydée Politoff had never previously acted when Rohmer gave her the lead in La collectionneuse (The Collector, 1967). She worked on her dialogue with him to personalize it, while painter Daniel Pommereulle played a tortured artist (also his first role), using one of his own razor-blade-covered works in a scene. For the haunting Les nuits de la pleine lune (Full Moon in Paris, 1984), a film that perfectly captures the lives of twentysomething nightclubbers in early-1980s Paris, it was as though Rohmer had completely absorbed the offscreen life of the lead, Pascale Ogier. She introduced him to the musical duo Elli et Jacno, who composed the score for the film; the party scene is cast with her friends; scenes included her own furniture; and she chose her wardrobe for the film based on her personal style, including an old-fashioned Hanro lace undershirt and Dorothée Bis duffle coat, which set a trend for young, hip Parisian women. The fact that Ogier died on the eve of her 26th birthday of a heart attack brought on by a drug overdose after a night at Paris’s Le Palace nightclub, not long after she had accepted the Best Actress award for her role at the Venice Film Festival, only intensified the impression that Rohmer’s fictions were a slice of real life.

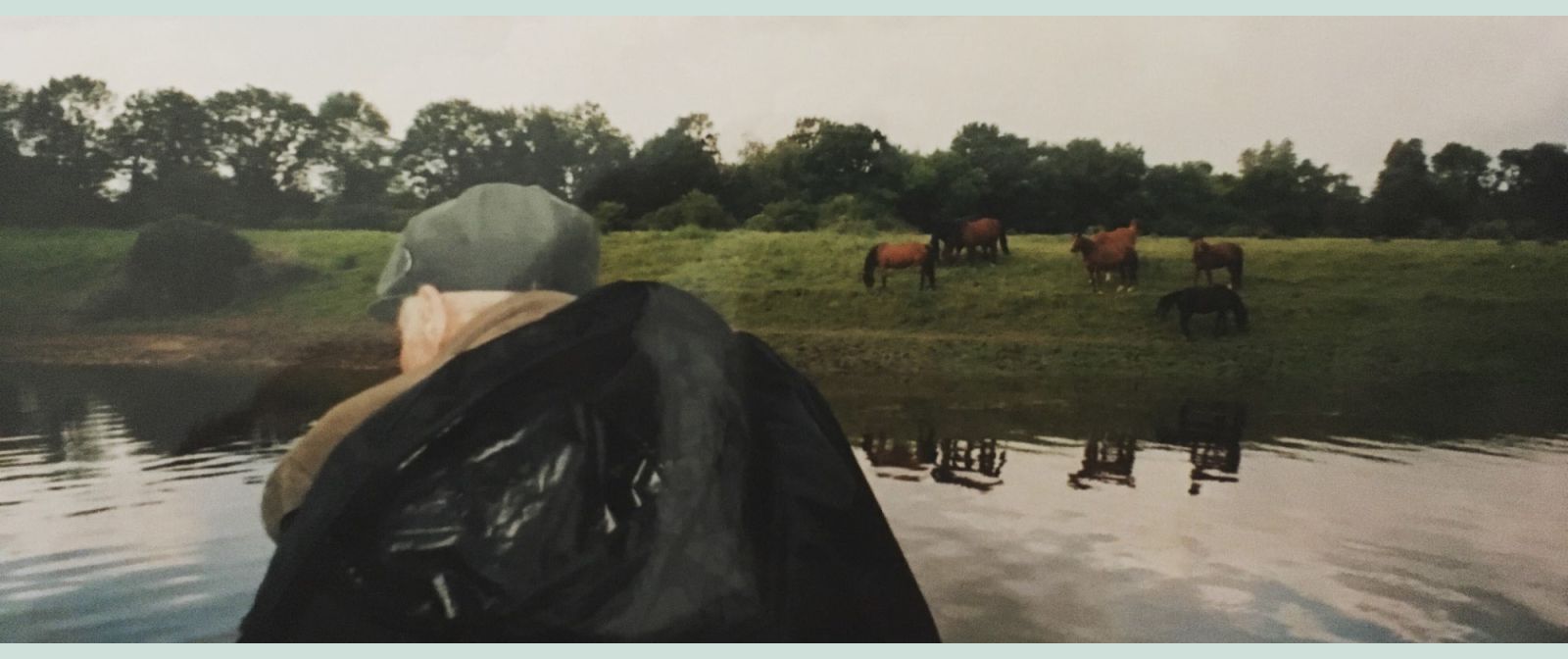

In 2006, Rohmer, 86, worked on what would be his last film. Les amours d’Astrée et de Céladon (The Romance of Astrea and Celadon, 2007) is based on L’Astrée, a long, multivolume tale about love among shepherds, nymphs and druids in fifth-century Gaul, written over 20 years by Honoré d’Urfé, a 17th-century French aristocrat. For Rohmer, the leisurely told story of L’Astrée was fertile ground: True lovers find themselves at odds through misinterpretations of events, are challenged by conflicting desires, and ultimately reunite after trials and tribulations. The film required three years of preparation. Rather than buy a copy of the more-than-5,000-page work, which he deemed “too expensive,” Rohmer sifted through it at the Bibliothèque Nationale, in Paris. While a line of students waited their turn, he copied every passage he found interesting on the library’s copy machine. Then he sent Etchegaray on a treasure hunt to find the perfect pastoral locations in France, which he insisted must be without fir trees, just as they would have been in the 17th century. “There are fewer characters than in the original for financial reasons, but I stuck to the exact text,” Rohmer announced proudly after the film’s release.

It took Etchegaray two years to convince Rohmer to cast Andy Gillet as Céladon, one of the lead roles. “The only guideline he gave me was that I had to find an actor with no Adam’s apple, because Céladon spends part of the film disguised as a nymph,” she says. Gillet was a model who had transitioned into acting, but the photos that Etchegaray originally showed the director didn’t convince him. It was only after he had turned down every other candidate that he agreed to meet Gillet. “I arrived at 26 avenue Pierre 1er de Serbie and saw the other names on the interphone: Godard, Schroeder, Ogier, nothing but legends,” Gillet tells me. “I said to myself: What is this building?” After “three or four hours over tea and stale cookies,” Gillet read a few passages from Racine’s Bajazet. He continued to meet with Rohmer for a year without really knowing if he had the role or not. “It was only after he gave me the musical scores I needed to learn for the guitar and the flute that I thought, Well, I must be cast now.” Rohmer found Stéphanie Crayencour to play opposite Gillet as Astrée after asking his cinematographer if she knew an actress whose profile resembled an antique Greek statue. “Rohmer’s films are nothing but this,” says Gillet. “His idea was that if he liked you, there would be no reason that what you proposed wouldn’t be right. He did everything like a 23-year-old!”

“The story has all the necessary Rohmerian ingredients: a question of beliefs, faith put to the test, and the interplay of love and sexual attraction in a comedy of misunderstandings.”

During the filming of Astrea and Celadon, Rohmer was suffering badly from scoliosis. Etchegaray frequently had to carry him on set. “He was incredibly cautious in his life, but he took enormous risks in his work because he was sure of what he was doing,” Etchegaray says. “So crossing the street against the light was a drama, but handing over the principal camera to me to film a critical scene when Astrée runs after Céladon at the start of the film didn’t bother him at all. He just said: ‘Oh, Françoise can do it.’ And I did.” It was during production that Rohmer began to realize that he wouldn’t likely live to make another film. However, he already had another film in him—a screenplay he’d been working on with Etchegaray called Mars et Mercure. It became his last, unproduced work, a final seed to stretch his longevity. Not only did he make Etchegaray promise to direct it, he also certified that wish by writing to the French cinema commission. Etchegaray has kept an original copy of the screenplay ever since.

The story revolves around a woman named Morgane, a karmic astrologer in Arles who refuses the love of her life, Matthieu, because she believes their astrological charts are incompatible. As it happened, it was Etchegaray who first wrote a script about star-crossed lovers doomed by astrology (La cigogne et le dragon, or The Stork and the Dragon). When Rohmer read it, he insisted it was bad. The next day, however, as they rode a bus together, he admitted there was something in the story that interested him. Etchegaray recalls him saying, “I don’t believe in astrology, but the subject is really faith. All my work is about faith.” He immediately set out to rewrite it, forging a special creative link between the two collaborators, and the result was Mars et Mercure. Indeed, the story has all the necessary Rohmerian ingredients: a question of beliefs, faith put to the test, and the interplay of love and sexual attraction in a comedy of misunderstandings. And like all things Rohmer, it’s also a collaboration. After the director’s death, Etchegaray and Gillet joined forces to ensure that Rohmer’s last screenplay would one day reach the big screen.

In the 14 years since, the two have worked painstakingly to secure the funding and attach the right cast, all in an attempt to keep the guiding spirit of Rohmer alive in the result. Such an endeavor, even in cinephilic France, hasn’t been easy. “The problem with Rohmer’s films has always been financing,” Gillet explains, “because in France it all comes from commissions with members who must agree. His screenplays are more like literary works, so there’s no indication of exactly how they’ll be filmed, and that leaves the committees in a quandary.” The other difficulty was the obvious: making a Rohmer film when the director has been dead for more than a decade. The proposal is that Etchegaray, Rohmer’s most trusted collaborator, will direct while Gillet will star as Matthieu. Morgane will be played by Crayencour. Other parts have been cast with young actors whom—Etchegaray and Gillet feel—Rohmer would have been drawn to, including Jeanne Damas, an Instagram sensation with her own clothing brand and a popular Paris following. Such an unusual approach has often led Etchegaray and Gillet to look for backing among Rohmer aficionados in the U.S. and Asia, who might be more predisposed to the unorthodox mission. “When you look for financing in France, people ask silly questions like, ‘Why haven’t we seen you at Fouquet’s lately?’” says Etchegaray, referring to the plush brasserie on the Champs-Élysées. “Rohmer was someone who believed in simplicity. He liked to say, ‘If I write a script with a Montblanc, it doesn’t make it better.’”

From left: The Collector, dir. Éric Rohmer, 1967; The Romance of Astrea and Celadon, dir Éric Rohmer, 2007; Claire's Knee, dir. Éric Rohmer, 1970; Full Moon in Paris, dir. Éric Rohmer, 1984

Interestingly, a second feature film has already been born from the quest. Over the years, as Etchegaray and Gillet pounded the pavement for support, they grew increasingly interested in the similarities and differences between Etchegaray’s original screenplay and Rohmer’s retelling. “Françoise is a Greek and Latin scholar like Rohmer, but she’s also an anarchist and a punk,” says Gillet of the director. “The stories in the two films are the same, but hers has more characters, more twists and turns. It’s much more burlesque than Rohmer’s version.”

In December 2022, the director and her crew began scouting locations around the southern town of Pézenas for La cigogne et le dragon, and soon after they began shooting, using a dozen actors and a crew of five. The film, renamed La loi du karma, will have its first unofficial screening for cast and crew on December 20, at the Filmothèque du Quartier Latin, in the fifth arrondissement—fittingly, Rohmer’s favorite Paris neighborhood. Gillet explains that the next step is for the film to be accepted by a festival (a requirement in the complex French cinema law for all self-financed films before they can be distributed to theaters). It’s Gillet’s hope that La loi du karma will attract passionate filmgoers to the Rohmer project. Once Mars et Mercure is produced, the plan is to show the two films together. “Françoise is Rohmer’s double, but she’s also his complete opposite. They’re like two facets of the same creative universe,” says Gillet. For those of us yearning for one final Rohmer romp, the legacy of the great director is safely in two sets of determined hands.