Mind Control

By Adam Nayman

Candyman, dir. Bernard Rose, 1992

Mind Control

Adam Nayman

How hypnosis became one of horror’s most enduring metaphors

October 16, 2024

“Now you’re in the sunken place,” intones the villainess of Get Out (2017), addressing both the film’s entranced protagonist, Chris Washington (Daniel Kaluuya), and the audience that’s been ensorcelled alongside him. That the rectangle representing Chris’s mesmerized point of view has the same anamorphic proportions as a movie screen clinches a killer conceptual joke: cinema as lucid dream, or maybe waking nightmare.

![]()

![]()

Get Out, dir. Jordan Peele, 2017

Director Jordan Peele’s visually and metaphorically potent image of “the sunken place”—a trancelike state in which Black victims are controlled by white hosts—stands as one of the great contemporary horror set pieces, and swiftly entered into the popular lexicon as a symbol of the dashed hopes of the Obama era, with Trumpian despair ascending. It also directly connects Get Out and its entwined motifs of sleep and dreaming with a long tradition of horror movies deploying hypnosis as both a narrative device and a conceptual lodestone—a lineage stretching all the way back to The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari.

From Rasputin and Svengali to Dracula and Fu Manchu, the culture of the early 20th century is rife with Mephistophelian manipulators with gazes like a bottomless abyss into which their helpless (and typically female) victims cannot help but fall. The archetype of the evil mind-controller is an old one: In 1920, German filmmaker Robert Wiene unveiled The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, a fractured fairy tale about a sideshow performer named Cesare (Conrad Veidt) lurching through a jagged expressionist landscape with his eyes wide shut. Although Cesare is a creature of the night, he lives in the eternal sunshine of the spotless mind; under the stewardship of the eponymous doctor—Werner Krauss, playing a fairground entertainer who is also an expert hypnotist—Cesare has been weaponized as a brainwashed assassin. He’s a (sleep)walking contradiction—an innocent acting as his master’s red right hand.

What Wiene’s film did—in tandem with French director Louis Feuillade’s popular silent crime serials Fantômas and Les Vampires—was consolidate the iconography of sinister hypnosis for a mass audience via film, a medium uniquely ripe for subliminal suggestion. Every critic who has ever tried to put a movie on the proverbial couch owes a debt to the German film theorist Sigfried Kracauer, whose landmark 1947 study From Caligari to Hitler: A Psychological History of the German Film analyzed The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari as a prophecy of incipient fascism—a reading made even more unsettling by lead actor Krauss’s real-life Nazi affiliations. Looked at from another angle, Caligari’s title character is recognizable as a stand-in for Sigmund Freud, then at the peak of his celebrity as the public face of psychoanalysis.

![]()

Conrad Veidt in The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari

![]()

The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, dir. Robert Wiene, 1920

The good doctor in Caligari also represents the myth of the filmmaker as an all-powerful authoritarian—a charismatic confidence man bending cast, crew and viewer to his whims. Writing about Werner Herzog’s 1976 film Heart of Glass, critic Eric Rentschler described the director as a “benevolent Caligari”—a reference to his having hired a hypnotist to work with the cast in the hopes of “portraying people on the screen as we have never seen them before.” “The actors’ trance is contagious,” wrote Janet Maslin of Heart of Glass in The New York Times, “and that has both its soporific qualities and its advantages.”

Over the years, Herzog’s ethically flexible tactics would be taken up by other envelope-pushing auteurs. Rumors have circulated for years that Andrzej Żuławski may have hypnotized Isabelle Adjani on the set of Possession (1981)—a theory that connects with the furious, uninhibited intensity of her performance. Virginia Madsen has confirmed that she was hypnotized by director Bernard Rose during the making of Candyman, his 1992 adaptation of Clive Barker’s short story “The Forbidden.” In the film Madsen plays a grad student who falls under the influence of the ghost of a murdered artist and son of a slave—a move that resulted in some of the most authentically glassy-eyed reaction shots ever captured on film.

In an interview on the DVD of Candyman, Madsen talks about her mounting discomfort with being controlled by her director, and it’s this singular mixture of focus and vulnerability—with each state heightening and deepening the other—that probably accounts for the prevalence of hypnosis in horror movies. Żuławski and Rose are not, strictly speaking, genre directors, and neither is Herzog, although he has made at least one horror classic—the exquisite and insidiously beautiful Nosferatu the Vampyre (1979), also starring Adjani, which exists in its own private thrall to Caligari.

Before helping to establish the templates for serial-killer and sci-fi cinema with M (1931) and Metropolis (1927), respectively, the Austrian-born director Fritz Lang adapted a series of novels by Norbert Jacques about an elusive mastermind trying to establish an “empire of crime.” The Third Reich’s cinephile brain trust banned Lang’s 1933 The Testament of Dr. Mabuse when they realized that its antagonist was intended to reflect their own distorted image: Mabuse is a cipher who transmits his influence through a series of technological prisms. The film’s cautionary tale about societal passivity (a thematic forebear of Get Out) hinges on a quasi-occult device wherein Mabuse’s consciousness is posthumously transferred—ambiguously but unsettlingly—into a human host who happens to be a psychologist lording, Caligari-like, over an asylum of his own.

“Ever the satirist, Peele updates the trope of the sinister hypnotist for an era of DIY seminars and racialized microaggressions.”

The existential anguish inherent in possession also figures centrally in the filmography of the Paris-born Jacques Tourneur—a resourceful craftsman of B movies in the 1940s and ’50s whose genius was the power of suggestion. Tourneur’s films are frightening more for what we think we see (or hear) than anything that actually occurs onscreen. The critic Raymond Bellour has written on Tourneur’s use of hypnotism as a symbol of trauma in Cat People (1942) and Curse of the Demon (1957)—a dual master class in Freudian slippage whose protagonists are caught between rationality and superstition, unsure whether to repress or unleash their shadow selves. A similar dynamic is at work in Tourneur’s 1943 film I Walked with a Zombie, a Caribbean gothic that fuses a Charlotte Brontë–inspired narrative with an ambivalent and haunting post-colonial critique, its white and Black characters united in a state of mutual catatonia. The pale, ethereal sleepwalker Jessica (Christine Gordon) and the hulking, hollowed-eyed zombie Carrefour (Darby Jones) are both spiritual descendants of Caligari’s Cesare, lost souls oblivious to their own status as flesh-and-blood voodoo dolls.

I Walked with a Zombie’s ensemble includes the Trinidadian dancer Rita Christiani, whose ebullient presence provides a bridge between Tourneur’s shoestring chiller and the experimental cinema of Maya Deren—the latter a scholar of Haitian Vodou culture whose work as a photographer, choreographer and filmmaker existed at the intersection of ethnography and avant-garde aesthetics. Shot in 1943 in West Hollywood with a 16mm Bolex camera for nearly $275 dollars, the 14-minute Meshes of the Afternoon (co-directed by Deren’s husband, Alexander Hammid) could be described as a Surrealist slasher film set entirely inside one character’s subconscious. Having fallen asleep sitting up in her home, the protagonist (played by Deren) pursues—or is she pursued by?—a hooded figure with a mirror for a face who is later glimpsed placing a knife in her bed. Between its relentlessly circular structure, syncopated editing rhythms and dreamlike symbolism, Meshes of the Afternoon functions both as a depiction of trance and a means of inducing it. While not categorically a horror film, its aura of ambient menace earns it a place of honor in the history of American nightmare cinema.

From left: I Walked with a Zombie, dir. Jacques Tourneur, 1943; Nosferatu the Vampyre, dir. Werner Herzog, 1979

Whether or not Deren’s film officially influenced Alfred Hitchock or David Lynch, there are trace elements of its style in mainstream landmarks like Psycho and Mulholland Drive—as well as the fetishistic thrillers of Brian De Palma, whose wicked and weird Sisters (1972) culminates in a final reel featuring a particularly brilliant instance of hypnagogic staging. After unraveling a bizarre murder case involving a pair of Siamese twins (both played by Margot Kidder), investigative reporter Grace (Jennifer Salt) is abducted and committed to a lunatic asylum by the duo’s doctor, a maniac whose surname—Breton, like André—is a sly Surrealist throwaway. Lying supine in a sanitarium room, Grace experiences an induced hallucination that momentarily aligns her psychically with Kidder’s infamous Blanchion sisters, who (it’s implied) were exploited as a clinical sideshow attraction by their unscrupulous physician. De Palma’s masterstroke is to shoot the scene unraveling their backstory from Grace’s point of view, so that the audience is effectively hypnotized into oblivion along with her. The style is in the service of a morbid punch line: Despite having solved the mystery, Grace’s hypnotic hangover prevents her from sharing her findings with the authorities. “There was no body because there was no murder,” she insists matter-of-factly—underscoring the devastating (and all-American) convenience of selective amnesia.

De Palma’s gambit would be modified in the ensuing decades by a pair of iconoclastic European filmmakers, with varying degrees of success. Spanish provocateur Bigas Luna’s cult shocker Anguish (1987) is a willfully bizarre mash-up of Grand Guignol tropes and grad-school theory, juxtaposing scenes from a cheesy neo-giallo about a socially awkward young man mutilating his victims at the behest of his mother with shots of a crowded Los Angeles movie theater, where giggly, above-it-all patrons prove similarly susceptible to the hypnotist-within-the-film’s “You are getting sleepy” shtick. Anguish’s attempts to draw parallels between mass spectatorship and spiritual somnambulism are somehow intricate and incoherent at the same time. By contrast, the films of Lars von Trier—whose fascination with hypnosis is such that a 1997 documentary about his work is called Tranceformer—are the work of a uniquely lucid dreamer. Von Trier has made a trilogy of horror films that are explicitly about mental manipulation: The Element of Crime (1984), Epidemic (1987) and Europa (1991) all feature extended passages with characters going under hypnosis. The last opens with the velvety voice of Max von Sydow inviting the viewer to gradually relax into a bleakly noirish post-WWII narrative with echoes of Kracauer (and Caligari and Hitler).

![<I>Cure</I>, dir. Kyoshi Kurosawa, 1997]() Cure, dir. Kyoshi Kurosawa, 1997

Cure, dir. Kyoshi Kurosawa, 1997![<I>Luz</I>, dir. Tilman Singer, 2018]() Luz, dir. Tilman Singer, 2018

Luz, dir. Tilman Singer, 2018![<I>Possession</I>, dir. Andrzej Żuławski, 1981]() Possession, dir. Andrzej Żuławski, 1981

Possession, dir. Andrzej Żuławski, 1981![<I>Sisters</I>, dir. Brian De Palma, 1972]() Sisters, dir. Brian De Palma, 1972

Sisters, dir. Brian De Palma, 1972

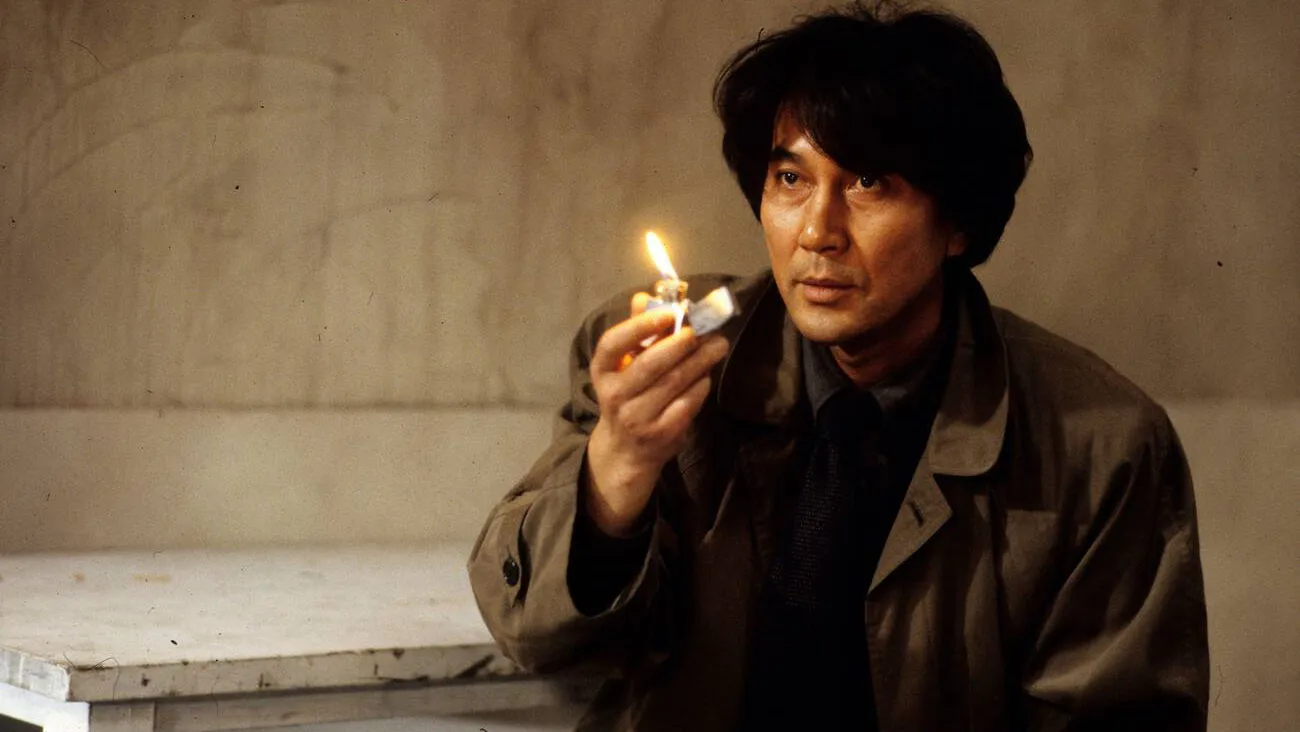

No inventory of hypnotically themed horror movies would be complete without a pair of millennial landmarks. The first is Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s Cure (1997), a supremely creepy procedural whose title serves, however unconsciously, as an homage to the last line of The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari: “Now I know exactly how to cure him!” Certainly, Kurosawa’s villain is working directly from the Caligari playbook: He’s a former psychology student turned drifter who uses his innate magnetism and knowledge of mesmerism to compel everyday Tokyoites into committing acts of lethal violence. The joke—and it’s a dark one—is that nobody in the film is actually acting against their basic instincts. On the contrary, by filleting their friends and neighbors, they’re simply doing what they’ve always dreamed. In Kurosawa’s masterpiece, hypnotism functions as a kind of psychic permission slip.

As for Get Out, it is, among other things, a thematic companion piece to both Candyman and I Walked with a Zombie. Here, interracial romance is supposedly no longer a taboo, while the voodoo masters are wizened, lily-white liberals trying to insert themselves—literally—into the consciousnesses of upwardly mobile young Black men. Ever the satirist, Peele updates the trope of the sinister hypnotist for an era of DIY seminars and racialized microaggressions. The scene in which aspiring photographer Chris is placed in a paralytic fugue state by his (white) girlfriend’s therapist mother (Catherine Keener)—all the better to eventually harvest his body to the highest Caucasian bidder—pivots on the idea of hypnosis as a means of anesthetizing “wokeness,” with the Black characters lulled surreptitiously out of alertness and into a servile state.

If there’s a late-breaking contender to this canon, it’s surely German director Tilman Singer’s marvelous lo-fi freak-out Luz (2018), which simultaneously exploits and deconstructs the cinematic properties of trance. The title character is a Chilean émigré (played by Luana Velis) who works as a cab driver in an unnamed metropolis. As the film opens, she’s reeling in the aftermath of a traffic accident that occurred under mysterious circumstances. Remanded to the custody of local police, she’s visited by a psychiatrist who proceeds to hypnotize and interrogate her about the collision as well as some enigmatic, possibly supernatural events from her past. What unfolds in the police station’s conference room—which has been reconfigured as a combination amphitheater and recording studio, with an audio booth equipped for simultaneous Spanish-to-German translation—is something between a séance, a radio play and a malevolent experiment, with the diabolical Dr. Rossini (Jan Bluthardt) as a Caligari stand-in. The film’s fragmented style not only distinguishes it from the received Kubrickian elegance of so much Zoomer-era “elevated horror,” but also reaches back to the perspectival gamesmanship and deeply ingrained themes of The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari—including the way it situates the viewer in a state of audiovisual disorientation (as critic Madeleine Wall writes, Luz’s “possession becomes our possession”). In spite of its discombobulating strangeness—or, more correctly, because of it—Luz is a small classic in a transfixing cinematic tradition that locates its power in the moment when the lights go down.