Somebody's Watching Me

By Calla Henkel

The Conversation, dir. Francis Ford Coppola, 1974

Somebody’s watching me

Remember when surveillance had a human face?

By Calla Henkel

March 7, 2025

Despite walking around with a device that collects and distributes my data as quickly as I expel it, I still find it impossible to fathom living under a system of such total personal surveillance as the German Democratic Republic before its reunification with the West in 1990. While the spies on my iPhone are all packed like sardines into my apps folder, the informers and information-gatherers of the former East Germany were human. Roughly one out of every 6.5 citizens acted as an informant for the state. This is a terrifying statistic, but oddly, in today’s endless slosh of digital surveillance, there is something almost poignant about the idea of being watched by an actual person—or to no longer be processed as, or by, an anonymous consumption algorithm.

The Lives of Others, dir. Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck, 2006

I am not alone in this desire. In the brief wake of TikTok’s departure from our phones this past January, the feed was inundated with reels of people jokingly bidding farewell to their personal “Chinese spies.” The register of those videos may have been absurdism, but the truth is that in using these apps we have all knowingly entered into a contract to be watched and data-mined—and yet we still want to be seen in full. To be understood by those watching. To reveal almost everything we can about ourselves.

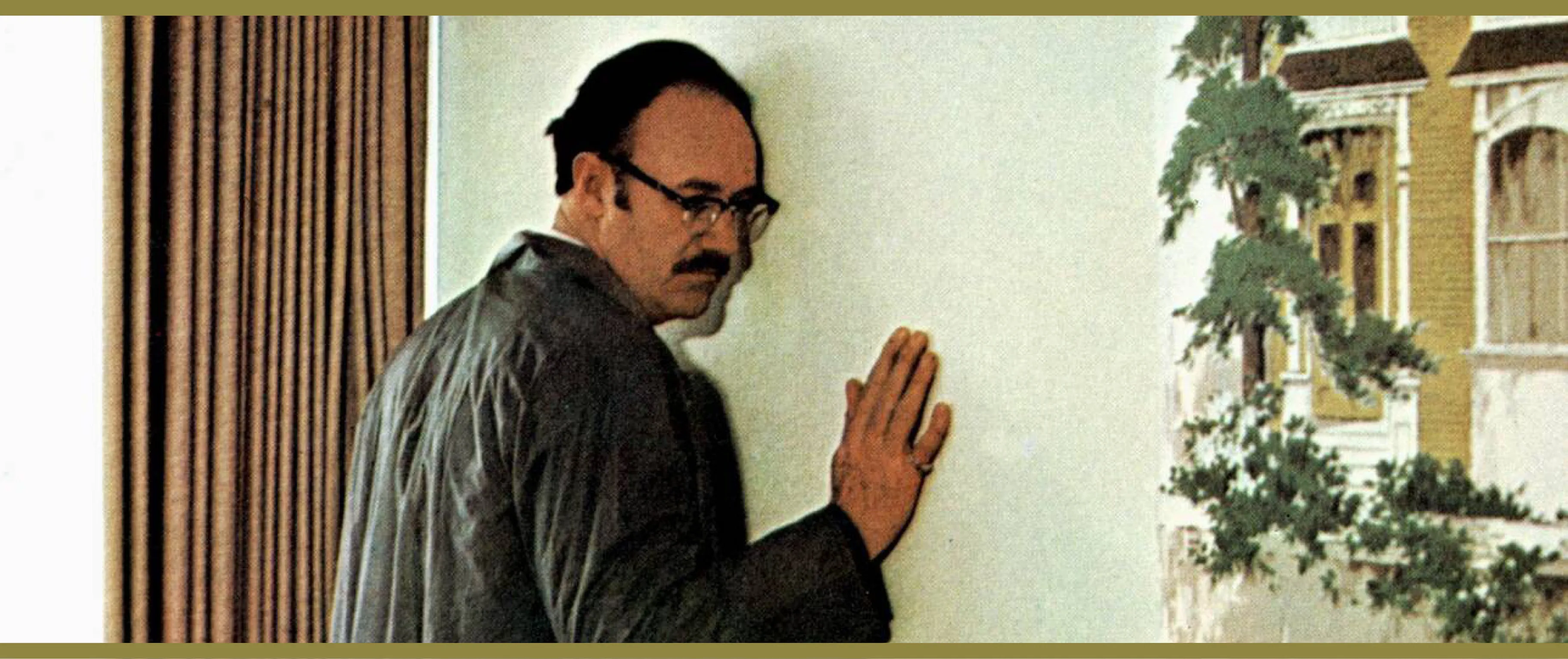

The uneasy world of human surveillance in the GDR is the setting for the bleak thriller The Lives of Others, directed by Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck. The plot swings into motion when Stasi officer Gerd Wiesler (Ulrich Mühe), perched on the balcony of an East Berlin theater holding a pair of binoculars, utters the words “I’d have him monitored,” indicating the famous East German playwright Georg Dreyman (Sebastian Koch) in the seats near the stage below. It makes sense that this order should happen inside a theater, where the boundary between observer and performer is both stark and universally understood. But soon the stage shifts and it is the playwright Dreyman under the lights.

Dreyman’s apartment walls and outlets are rigged with the intrusive wires of the socialist party’s surveillance machine. Once again Stasi agent Wiesler is perched above, this time in the building’s attic, listening to every word exchanged between Dreyman and his actress girlfriend, Christa-Maria Sieland (Martina Gedeck). Wiesler is trying to ascertain if the pair are really the loyal communists they publicly claim. But of course it gets more complicated: Wiesler becomes emotionally drawn to the artistic couple, whose lives are filled with passion, poetry, Brecht and intellectual friendships. When one of Wiesler’s higher-ups, who is in love with Christa-Maria, begins to use the surveillance of the couple to serve his own carnal interests, Wiesler’s allegiances to his party waver.

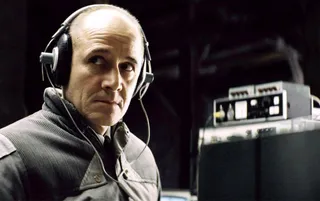

Released in 2006—one year before the advent of the iPhone—the film is a starkly anti-communist portrait of the GDR, but it also works as a window into the complexity of watching. Every frame negotiates the tilted stage of surveillance. As with Francis Ford Coppola’s 1974 neo-noir drama, The Conversation, Donnersmarck’s film is largely framed through the emotional register of the watcher. In The Conversation, Harry Caul (Gene Hackman) is a private surveillance expert in San Francisco who tries to keep a distance from his subjects but becomes drawn into a routine job when he discovers what he believes to be a murder plot. Both films challenge the ethics and loyalty the surveyor commits to his cause. Stasi agent Wiesler begins The Lives of Others as a staunch communist who’s only interested in protecting his party, while The Conversation’s Caul is portrayed as a single-minded capitalist. Caul tells his assistant, “If there’s one surefire rule that I have learned in this business it’s that I don’t know anything about human nature. I don’t know anything about curiosity. That’s not part of what I do. This is my business.” But both Caul and Wiesler ultimately provide the fatal human filament: Their emotional responses to what they hear change the outcome for everyone involved.

At the beginning of The Lives of Others, Dreyman seems unsure as to why his friends are so disillusioned with the state. After all, his plays are being staged, his girlfriend is cast in starring roles, he feels supported—until his close friend, the blacklisted director Albert Jerska, dies by suicide. Only after Jerska’s death does Dreyman comprehend the state’s oppressive nature, and he decides to write a scathing article about the undocumented suicides in the GDR, which will be published in a Western magazine. Before he begins work on the text, Dreyman tests to see if his apartment is bugged, loudly discussing a fake plan to smuggle a friend out of the East. Wiesler is, of course, upstairs listening, but instead of alerting the border guards he decides to look away, softly saying, “Just this once, my friend.” In this brief moment, Dreyman is speaking directly to Wiesler and Wiesler chooses not to act, knowing that reporting his subject would terminate his ability to listen. His decision to turn a blind eye tightens the knot of the film and the two men’s fates.

![]()

Gene Hackman as Harry Caul

![]()

1980s East Berlin in The Lives of Others

Given the state of the world in 2025, Wiesler’s shift toward feeling emotionally protective of his subject feels shockingly humane. This past January, when Trump was sworn in for his second term, Mark Zuckerberg, Jeff Bezos, Elon Musk and TikTok’s CEO Shou Zi Chew—a proverbial cabal of the billionaire tech overlords who own our data—were all present. The message felt clear: There is no longer a division between church and state. There is no protection. When even our air fryers are collecting our personal information and selling it to brokers, everything we say, search or buy is amassed as information, chopped and screwed and fed to the highest bidder to create lucrative consumer profiles. No one cares about our good intentions or how beautiful and full our lives are. Our dignity and human spirit are utterly beside the point. We are cogs purely for profit.

Thus, The Lives of Others, set in 1984, provides a wrinkled nostalgia. Yes, it’s a portrait of a dark and oppressive time in which state power overrode the ideals of socialism and leached into policing personal freedom. But it also proposes the idea that art can transform even the most hardened of zealots. Through his surveillance, Wiesler is exposed to theater, poetry and love, eventually sneaking into Dreyman’s apartment to steal his copy of Brecht. As Wiesler lays on his own sad brown couch, his world is expanding as he reads, while simultaneously his eyes are opening to the flaws of the communist party to which he has dedicated his life. When Dreyman finally sets about writing his article on the hidden number of suicides, he and his friends, still nervous for their safety, decide to speak of the project as if they are writing a play celebrating the 40th anniversary of the GDR. This ruse creates a meta narrative. Wiesler knows there is no play, but he reports it as if it were so to his superiors. He protects Dreyman, and in doing so, becomes the sole audience member for this so-called play.

Theater is used as both a metaphor and threat. “I am your audience,” Wiesler tells Christa-Maria when he sees her in the local bar, referring to her turns on the stage, but also to his (unknown to her) role of listening to her and her boyfriend’s lives. In the end The Lives of Others is about the slippage of who gets to control the narrative—and what happens when the passive listener finally intervenes, moving from audience to actor. In The Conversation, Caul, suspecting a murder plot, intervenes by withholding the tapes he’s made of a couple speaking softly to each other in a park, prompting him, and the situation, to spiral out of control as he actively tries to thwart the murder. Similarly, Wiesler attempts to cover up for Dreyman, removing evidence before the Stasi can search his apartment.

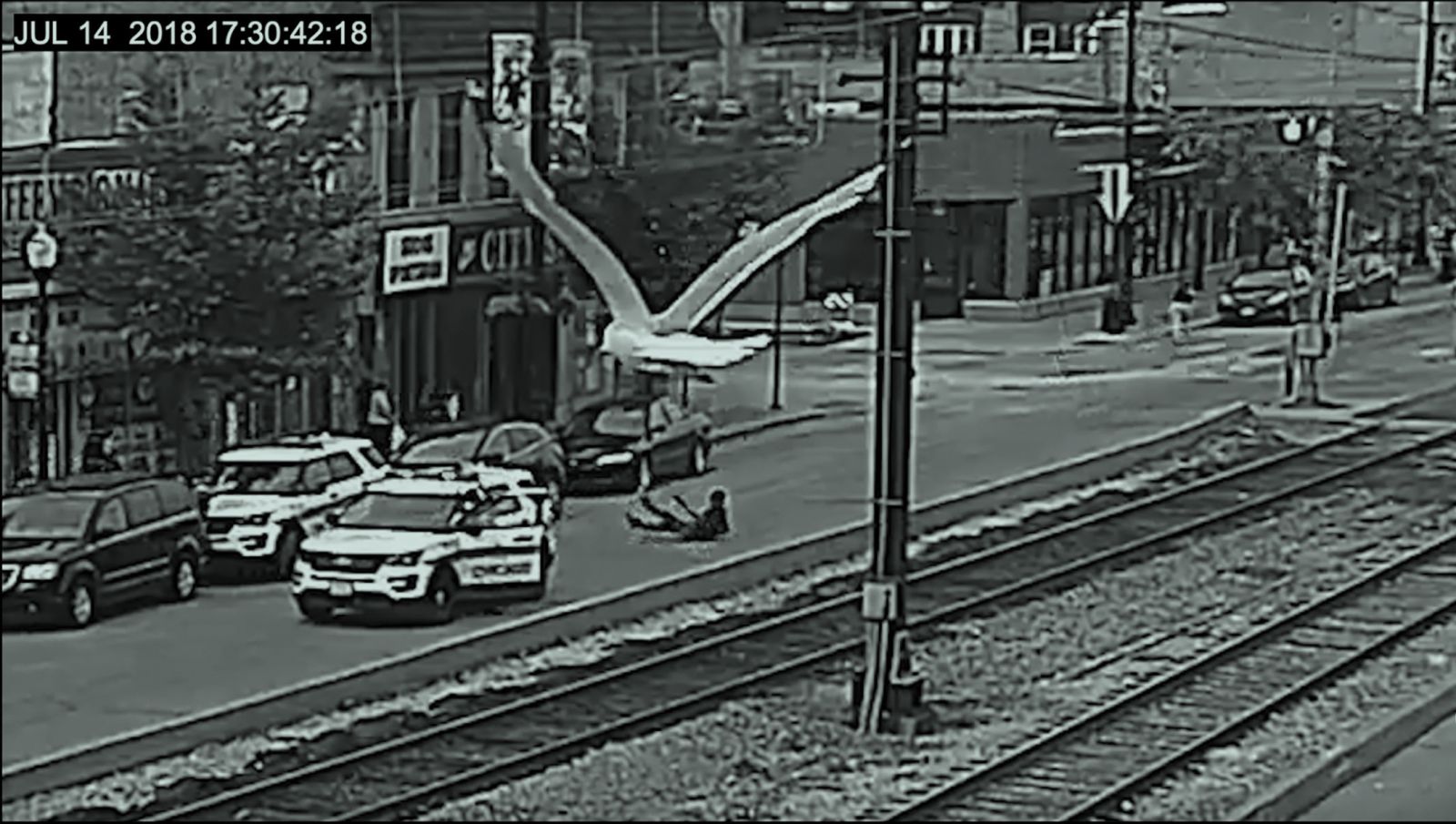

Incident, dir. Bill Morrison, 2023

Compared to such displays of empathy, today’s modes of surveillance feel far less sympathetic. The technology is no longer relegated to a group of highly trained individuals with state-of-the-art headphones. Instead, the profusion of digital cameras has enabled multiple viewpoints, and we are now faced with the question of who has the power to collect and control the data. Consider director Bill Morrison’s Oscar-nominated documentary short Incident (2023), which reassembles an archive of security footage from the 2018 shooting of Black barber Harith “Snoop” Augustus by a Chicago police officer. There are dozens of vantage points that capture what looks at first like a pleasant summer afternoon on an inner-city street but it quickly escalates to murder. Voices of infuriated witnesses are overcut with the body-cam footage of police. What is most disturbing is how the officers themselves begin to “perform” a scripted version of reality immediately after the incident and repeat it frantically to one another, as if convincing themselves of this “truth.” In this fictional retelling Augustus reached for his gun first, pulling it on the police, who were forced to shoot because their lives were in peril. It becomes clear that the officers are effectively rehearsing a new narrative right before our eyes and ears, and if not for the body cam and other surveillance footage, we wouldn’t witness this rewriting of reality. After the film was released, the Chicago City Council passed a provision allowing cops to turn off their body cams during conversations that follow incidents and to delete any post-event discussions—meaning we will no longer have access to any potential fabrication of events. Incident made the system respond, but only to tighten its grip on controlling the narrative in favor of the system itself.

The Lives of Others stands not only as a cautionary tale but also as a romantic letter, a reminder that we have the power to intervene and possibly transform the system, one person at a time. But that possibility flickered in that period only because there were humans with uncertain hearts and minds doing the watching. In the current era of anonymity, of endless data collection, where it increasingly feels like no one but an algorithm is at the controls, it’s hard to understand how we can bend the will of a system, or how our art, lives and love can create change. Maybe, as in Incident, we have to try to turn the tools of the machine against itself.