Top 10: Nature as Character

By Emma Reeves

Picnic at Hanging Rock dir. Peter Weir, 1975

Top 10: nature as character

emma reeves

Movies where the environment plays a starring role

April 18, 2025

In honor of Earth Day, I’ve been thinking about films in which the natural world plays a vital part in the story. I don’t mean simply landscape as ambience, a bucolic or moody backdrop for the drama unfolding in the foreground, but rather film narratives that couldn’t exist without the tension brought by Mother Nature. For a few years now, I have been involved with a nonprofit called ClientEarth, a global environmental-law organization that holds polluting companies accountable for climate crises. I am reconciled to the idea that the natural world is inherently a pretty violent place. The arrogant human instinct to tame it goes hand in hand with the extractive tactics of capitalism. That is what ClientEarth has been set up to address. There are multiple organizations across the world focused on planetary protection, rewilding and land conservation. The existence of these initiatives is a source of hope.

For some directors, the challenge of filming in extremely adverse natural conditions becomes part of the production process—and even sewn into the story. Werner Herzog’s Aguirre, the Wrath of God (1972) and Fitzcarraldo (1982), for example, were each set in a combination of the Peruvian and Brazilian rainforests. Both films tell tales of colonial exploration; as a consequence of these real-life conquests, huge areas of rainforest are now destroyed. In the Les Blank documentary Burden of Dreams (1982), about the making of Fitzcarraldo, Herzog admits to be “challenging nature itself” as he makes the film. He talks of the landscape’s misery and vileness, claiming that the birds are screeching in pain. But ultimately he speaks of the environment with reverence: “We have to become humble in front of this overwhelming misery and overwhelming fornication, overwhelming growth and overwhelming lack of order…. There is no harmony in the universe…. But when I say this I say this all full of admiration for the jungle. It is not that I hate it. I love it. I love it very much, but I love it against my better judgment.”

In choosing the 10 films below, I have attempted to exhibit nature in all its wild and violent glory, while steering clear of the wealth of nature documentaries (such as the Planet Earth series) or recent eco-disaster blockbusters like Don’t Look Up (2021). It’s impossible to represent every ecosystem on the extraordinary planet we inhabit. This list omits countless countries and even whole continents. It also misses out on the seas and the oceans. The intention is to encourage watching (or rewatching) the films selected, paying acute attention to their natural setting. In a time when there are increasing efforts to acknowledge that nature has legal rights to exist, perhaps it is also time to see nature credited at the end of any film in which it has a starring role.

Picnic at Hanging Rock, dir. Peter Weir, 1975

1. Picnic at Hanging Rock, dir. Peter Weir, 1975

Set in rural Victoria, Australia, in 1900, this cult classic by Peter Weir, a leading figure in Australian New Wave cinema, follows a group of teenage girls and their teachers from a provincial boarding school as they journey to the eponymous volcanic rock formation to celebrate Valentine’s Day. The headmistress warns that even though Hanging Rock is “a geological marvel,” it’s “extremely dangerous.” Mysterious disappearances ensue as several girls, in pristine white Victorian clothing entirely inappropriate for the heat and terrain, climb up into the rocky outcrop. A montage of the natural flora and fauna, and the rocks themselves, imply that nature is watching, alert to their intrusion. Three of the girls scandalously remove their shoes and stockings—throwing off the shackles of their repressive societal norms—and wander trancelike into a crevice.

An oppressive atmosphere, repressed teenage emotions, class struggles, sapphic longing and boredom are the stepping stones that lead to these unexplained vanishings, all magnified by the craggy setting shot in dappled light and shadows. The disappearances even lead to the suicide of a student who was not at the picnic. She has thrown herself from the top of the boarding school building and is found hidden in the dense plants inside a greenhouse. The natural world has claimed yet another victim. The film embodies the “white vanishing myth,” in which a vulnerable white settler disappears, without a trace, into the pitiless untamed landscape and thus reinforces the need to “civilize” the landscape. The real-life Hanging Rock is now part of a nature reserve.

Watching the film again in 2025, it’s hard to ignore the absence of any overt reference to the aboriginal people who considered Ngannelong (Hanging Rock) as sacred. The outcrop, a former volcano, acts as a natural dividing point between three aboriginal tribes who have been in the area for 26,000 years. It exerted such power over those tribes that they refused to climb it. On approaching the rock, Irma, the only girl among the climbers to survive, declares that the rock has been “waiting a million years just for us.”

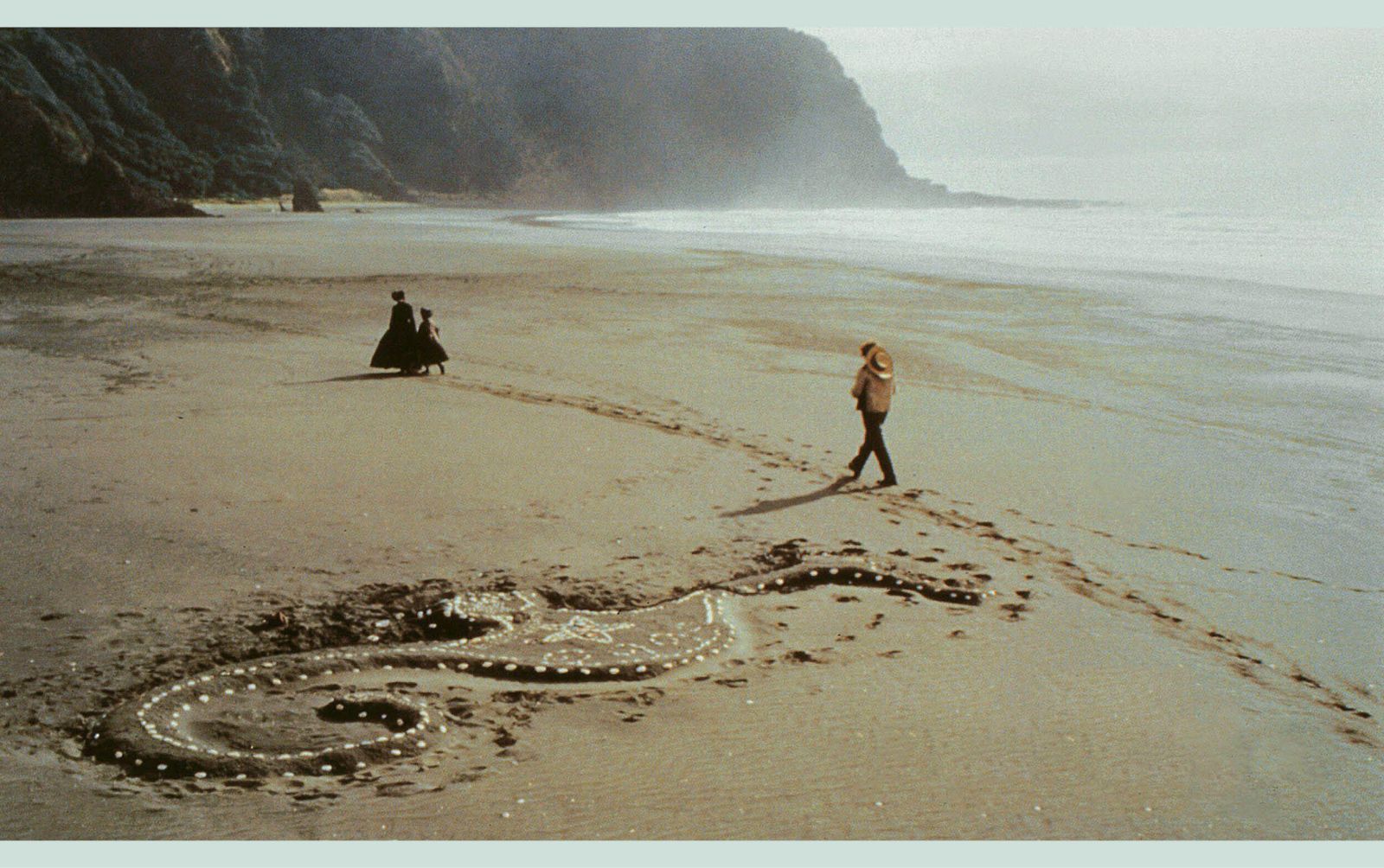

The Piano, dir. Jane Campion, 1993

2. The Piano, dir. Jane Campion, 1993

The Piano catapulted its writer and director, Jane Campion, into the limelight when it was awarded the Palme d’Or in 1993 and went on to be nominated for eight Academy Awards. In the film’s opening sequences, the viewer is introduced to a mute woman, Ada McGrath (Holly Hunter, who won an Oscar as well as the Best Actress award at Cannes for her performance), and her young daughter, Flora (Anna Paquin, who also won an Oscar), just before they make the long boat journey from their native Scotland to a remote part of New Zealand. Ada is intended for an arranged marriage; the year is 1851. They finally arrive in a canoe, deposited on a torrid, windswept beach, the scale of which feels both otherworldly and threatening. The eponymous piano is perilously strapped to the canoe being rowed ashore, but that’s as far as it can go for the day. After sleeping a night on the beach, mother and daughter reluctantly leave the prize possession behind, with Ada, high on a hill, looking down on the piano facing the rapidly approaching tide. Michael Nyman’s score, with its atmospheric swelling rhythm, gives voice to Ada’s grief.

This iconic scene was filmed at Karekare Beach, in the Waitākere Ranges Regional Park, West Auckland. The cinematographer, Stuart Dryburgh, was given a file of research by Campion that included early-19th-century photographs, paintings and autochrome images that informed the muted palette of blues and grays, lending the film its signature aesthetic. I had not watched The Piano since it was first released, and on my recent viewing something new caught my eye: There are two homes that work as principal settings. One is inhabited by the domineering white settler husband, Alisdair Stewart (Sam Neill), the other by his neighbor, George Baines (Harvey Keitel), who has taken on Maori codes and customs. The Stewart home is surrounded by aggressively cleared land, a literal slash and burn, some of the trees still shrouded in smoke from fire. Stewart is in constant negotiation with the Maori, as he tries to buy more of it. His insensitivity underlines his colonizer assumptions, but the Maori refuse to sell him more as it is tapu, or “sacred.” Stewart cannot comprehend this line of reasoning. On the way back, he angrily questions Baines, who had acted as translator: “What do they want the land for? They don’t do anything with it. They don’t cultivate it, they don’t burn it back. Nothing. I mean, how do they even know that it’s theirs?” By contrast, Baines’s house, a bohemian wood cabin, is on higher ground, set in a densely lush landscape. Here, the beloved piano is installed once Baines barters some of his land to Stewart in return for piano lessons from Ada. The walk that Ada takes, from one domestic setting to the other, to reach her piano, mirrors the battle for her affection between the two men. The controlling and repressed Stewart, at odds with the landscape, goes to war with Baines, the elemental force who has chosen to respect the environment rather than conquer it.

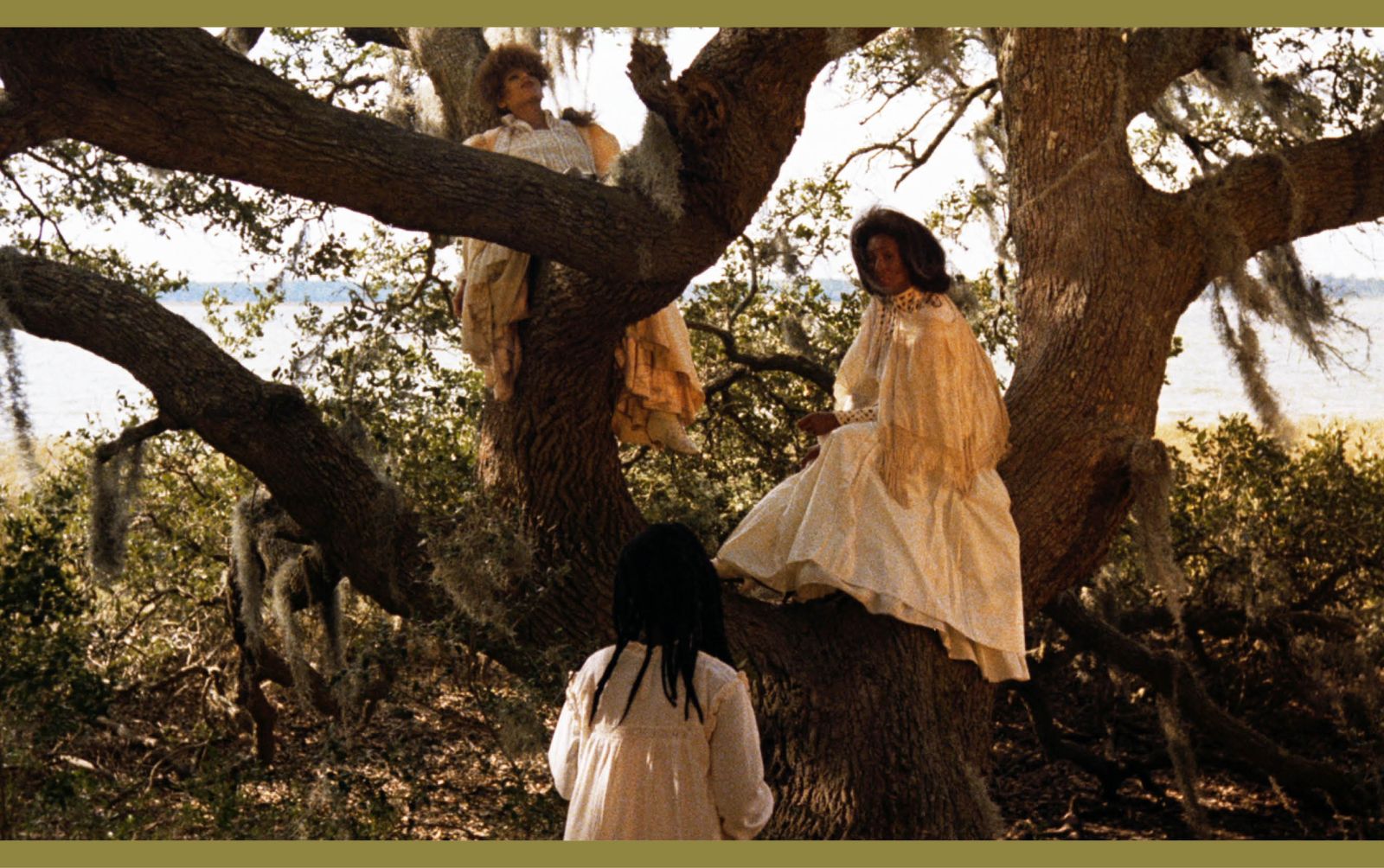

Daughters of the Dust, dir. Julie Dash, 1991

3. Daughters of the Dust, dir. Julie Dash, 1991

Director Julie Dash is a descendant of Gullah people who still live in the isolated subtropical islands, known as the Sea Islands, that lie off the coast of South Carolina and Georgia. Her landmark film Daughters of the Dust, set in 1902 and filmed on St. Helena Island, is a feminist meditation on a place arrested in time and saturated with ritual. It’s centered on three generations of Gullah women as they face migration to the mainland, all surreally taking place over the course of a single day. Daughters of the Dust is the first feature directed by an African American woman to be granted wide theatrical release in the U.S., and it features prominent collaborations from two other major Black artists who helped shape its exquisite nonlinear form: multimedia star Arthur Jafa, who served as cinematographer, and acclaimed painter Kerry James Marshall, who drove the production design. The movie has had a profound cultural impact—for instance, it was a direct reference in Beyoncé’s 2016 album Lemonade.

Dash’s visual radicalism derives from her scholarly interest in film. While studying for her master’s degree at UCLA, she tested film stock, choosing Super 35mm film with an Agfa-Gevaert negative to achieve the luminous quality and rich skin tones of her subjects. As the islands are officially protected areas, it wasn’t possible to bring in generators or cables for the production, so Jafa shot the film using only natural light boosted by handheld reflectors. The entire budget was $800,000, and it was shot over 23 days. (Notably, the film was restored to its glorious palette in 2016.) Dash has spoken of the in-depth research she did to prepare her actors and crew, including compiling pamphlets on the history of the Sea Islands. “The sun was coming up, we’d be getting ready to shoot at 5 a.m., knowing this was hallowed ground, this was our Ellis Island. The waves would be rolling in, and sometimes people would be weeping,” Dash said in a New York Times interview.

Originally inhabited by Native American tribes including the Creek and Guale, St. Helena Island is part of the marshy ecosystem of islands and riverways skimming a stretch of the southern Atlantic coast that includes Savannah and Charleston, two cities that played a pivotal role in the transatlantic slave trade. Dash also committed to having a Native American presence in the film to honor the intertwined histories of the enslaved Black community and the indigenous inhabitants. The character St. Julien Lastchild, a Cherokee who has refused to leave the island, plays a central role in the storyline.

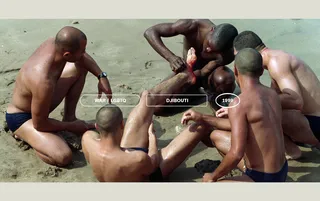

Beau Travail, dir. Claire Denis, 1999

4. Beau Travail, dir. Claire Denis, 1999

Claire Denis was born in Paris, but her formative years were spent in multiple African countries that were, in the 1950s of her youth, still French colonies. Denis has often referred to herself as “une fille d’Afrique,” and several of her films are set in Africa. Djibouti, on the Horn of Africa, where Beau Travail takes place, became an independent republic in 1977. The film is focused on a small group of soldiers in the French Foreign Legion who are stationed in a scruffy seaside port with a bar absurdly named Bar des Alpes. The uniformed men are startlingly out of place, apart from when they provocatively dance with the young local women inside the village disco. From the start of the film, we are hyperaware of the desert landscape surrounding the town. In an early montage, a dusty train traverses the wild and barren expanse. Where the parched land meets the blue sea, there is a ragged edge rather than a gentle beach. The film’s cinematographer, Agnès Godard, captures this extreme environment with an exquisite painterly eye, relying on a limited range of sun-bleached colors. The days pass in the ritual of endless physical exertion, on land and in seawater, under the relentless rays of the sun. The military exercises, often shirtless, were choreographed by ballet dancer Bernardo Montet, who also plays one of the soldiers, and the hypnotic and homoerotic movement of these peak-fitness sweating bodies tells the unfolding story in this brutal setting.

The dynamic of this isolated group is soured by the psychotic jealousy of a sergeant named Galoup (Denis Lavant) toward a handsome young soldier named Gilles Sentain (Grégoire Colin). We see Sentain rescue a drowning soldier after a military helicopter explodes over the sea. Another soldier dies. Red blood stains the blue water. Sentain is praised for his action. He is also well-liked by the men. Galoup plots his revenge by deciding that the troop must travel farther out into the desolate countryside to take up residence in an abandoned building in a hostile volcanic landscape overlooking distant islands. While there, Galoup orders them to fix a road, heavy labor in the heat. Galoup eventually conspires to abandon Sentain alone. Despite the soldier’s physical prowess, he is no match for this inhospitable terrain and relentless heat, completely devoid of shade. Sentain is determined to find his way back to the base camp but is ultimately discovered by a group of singing nomads leading camels across an expanse of gleaming white salt flats. He is close to death, burned to a crisp by the sun’s rays.

For his actions, Galoup is court-martialed. He tells his story retrospectively, back in civilian life in the drab cityscape of Marseille. The orderly French port city cannot compare to the sweeping African landscape, emphasizing all he has lost.

“The days pass in the ritual of endless physical exertion, on land and in seawater, under the relentless rays of the sun.”

Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives, dir. Apichatpong Weerasethakul, 2010

5. Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives, dir. Apichatpong Weerasethakul, 2010

Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives was originally part of “Primitive,” a project founded by artist and experimental filmmaker Apichatpong Weerasethakul in 2009, cinematically exploring aspects of the rural Isan region of northeastern Thailand. Weerasethakul was raised there and set his dream-life film about existence and reincarnation in its dense jungles and lush surrounding landscape. Based on a book written by the abbot of a local Buddhist temple, documenting various visits from people at the end of their life, the Palme d’Or–winning Uncle Boonmee opens with a quotation written in both Thai and English: “Facing the jungle, the hills and vales, my past lives as an animal and other beings rise up before me.” What follows is a languorous sequence where a water buffalo’s tether breaks free from its tree. We follow the water buffalo deeper and deeper into the jungle until a man with a sickle enters the frame and persuades the animal to follow him, tugging on its rope.

Uncle Boonmee (Thanapat Saisaymar) is a farmer suffering from late-stage kidney disease. His modest farm, consisting of fruit trees and beehives, is set in a surreal dimension where the natural and supernatural coexist. There is a relentless hum of insects and wildlife. Even when there is faint music, the insect sounds dominate. Boonmee speculates that his illness is the karmic result of killing too many communists—and too many insects with chemicals in order to save his fruit harvest. It may be that the same karma was responsible for the death of his wife, Huay, and the disappearance, 13 years prior, of his son Boonsong.

Huay appears as a ghost, and then Boonsong materializes in the form of a hairy, red-eyed, ape-like being who also appeared briefly at the start of the film. The viewer is not expected to make sense of these reincarnations. There are fluid exchanges between present and past, animals and humans. The natural world allows all of these contradictions to exist at once. Before Boonmee’s ultimate transmigration, he leads the ragtag group from the house to a magical cave, reached after a strenuous trek through the jungle at night. It is hard to know if this cave is real or imagined—the walls glitter with tiny points of light and a pool of small fish lives there. When the group lies down to rest and Huay unplugs Boonmee’s dialysis bag, life drains from him. Boonmee had remembered being born inside the cave, and this return to his birthplace alludes to the cyclical nature of birth and death that is part of Buddhist philosophy.

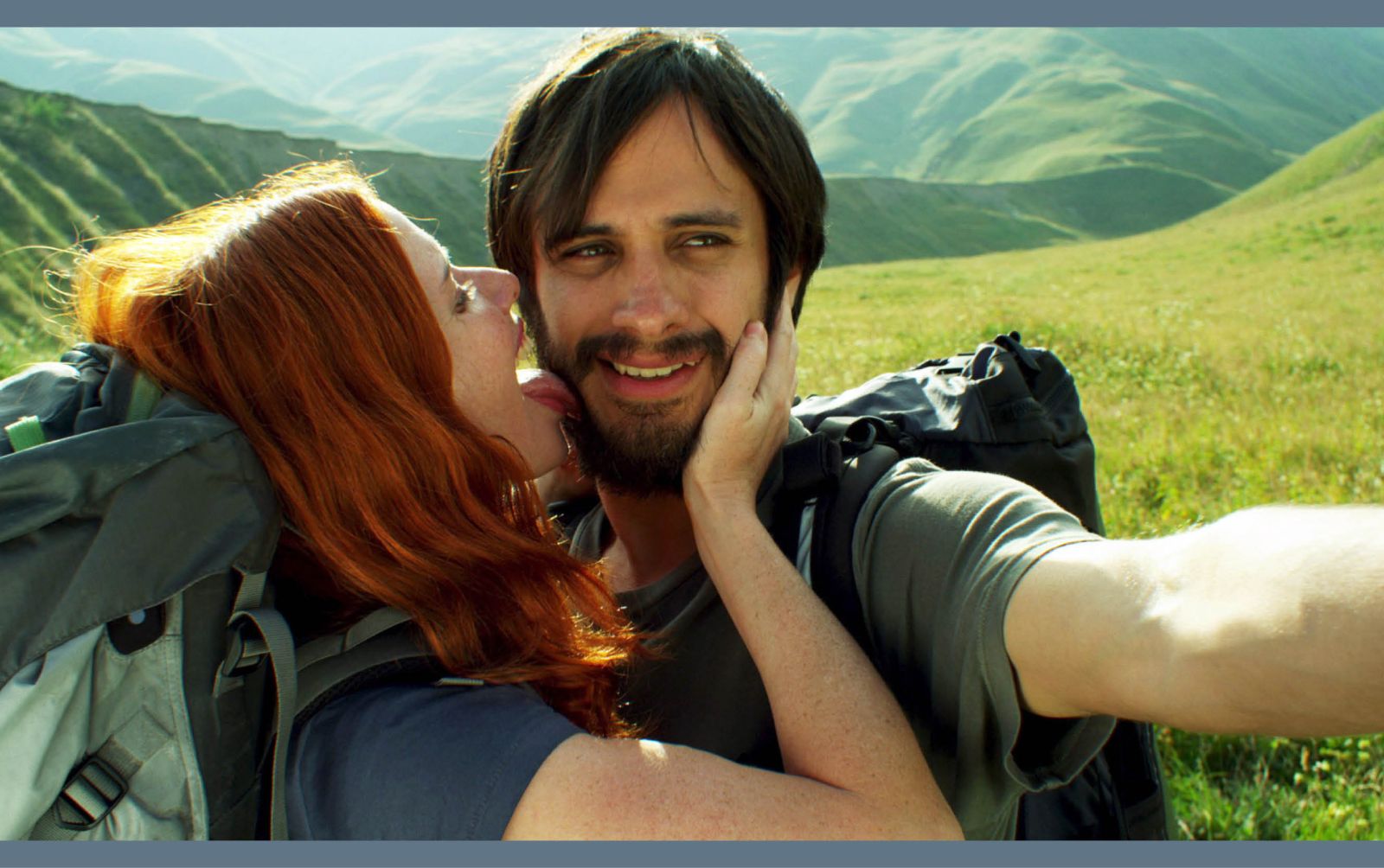

The Loneliest Planet, dir. Julia Loktev, 2011

6. The Loneliest Planet, dir. Julia Loktev, 2011

Part of what draws me to this quiet thriller is its setting in the expansive Georgian landscape of the Caucasus. A young couple (Gael García Bernal and Hani Furstenberg) embarks on a multiday mountain trek, setting off from a village with an older guide (Bidzina Gujabidze, not a professional actor but a famous Georgian mountain climber). We learn that the couple is engaged to be married, and their curiosity and enjoyment in both the landscape and each other is palpable.

Georgia, formerly part of the Soviet Union, has seen little investment in its rural areas. As portrayed in the film, most of the buildings and vehicles in the mountain town are decayed or abandoned. Nature seems to be reclaiming its territory. The pristine mountainous vista is a lush green, contrasting the broken machines of the old empire. Julia Loktev has chosen a documentary-style approach, relying mainly on naturalistic semi-improvised dialogue and a lot of loose, handheld camerawork. She has succinctly summed up the film as being about “three characters, a landscape, and a camera.” While the trek is not particularly strenuous, there is still an underlying sense of danger, with the mountains looming forebodingly over the couple. They seem naive in comparison to their guide’s intimate knowledge of the landscape. At one point he offers them an herb, which they eat enthusiastically. He then jokingly tells them it’s poisoned. For most of the journey, the three-person group is startlingly alone, except for the occasional encounter with an unexplained noise or animals. When they finally cross paths with three locals, the exchange quickly escalates into violence: A gun is pointed at Bernal’s face and he hides behind his fiancée. Quickly correcting this show of weakness, he steps in front of her as a source of protection, but the damage has already been done. In the face of this unexpected threat, the couple seem woefully unprepared for potential dangers, and their urbane naivete and trusting nature are challenged.

As none of the spoken Georgian dialogue in the film is translated into subtitles, a tremendous sense of alienation accrues between the environment and the viewer. It’s never clear why the three locals reacted so unfavorably to the couple. Through body language, you understand something is irrevocably broken between the lovers. They continue their expedition in silence and at a distance from each other—an alienation underscored by recurring long-distance shots of the trio. These humans seem like petty players in the face of the massive primordial setting.

.jpg)

Clouds of Sils Maria, dir. Olivier Assayas, 2014

7. Clouds of Sils Maria, dir. Olivier Assayas, 2014

In the opening sequence of Clouds of Sils Maria, the two main characters are traveling on a train toward Zurich. Juliette Binoche plays the cantankerous veteran actress, Maria Enders, and Kristen Stewart, her long-suffering assistant, Valentine. They are locked in an intense battle of wills from the outset. Seen through the cabin windows, the train works its way ever deeper into the snow-capped mountain valleys of Switzerland. The landscape is a brooding presence in contrast to the confined conditions of the carriage, and the heated relationship between the star and her assistant.

Much of the film subsequently takes place in the remote picturesque mountain village of Sils Maria, specifically in the isolated home of a recently deceased fictional playwright named Wilhelm Melchior. The valley of Sils Maria is known for an unusual naturally occurring cloud formation called a Maloja Snake, shaped by the curvature of the valleys. Melchior had written a play named after the cloud phenomenon in which the young Enders starred as a teenager 20 years ago. The play is a romantic lesbian drama à deux, and now Enders is in rehearsal for a reprisal, although this time she will be playing the older character. As Maria and Valentine rehearse and run lines, the relationship of the two women blurs between fiction and reality. But another competing character in the film is the awesome backdrop of looming mountains and changing seasons, haunted by this bizarre cloud formation. It is on a last hike through this breathtaking scenery that the two women set out to catch sight of this celestial event. It is a rare sight, only occurring when specific conditions are in place. Maria spends much of the trek oblivious to the sublime beauty around her, relentlessly jabbing at Valentine and questioning her ability to navigate with a paper map. She even doubts the existence of the cloud. Nevertheless, arriving at the end of the trek, Maria channels her youthful self and cannot contain her excitement when she realizes that the Maloja cloud is really appearing before her eyes. Only she finds herself totally alone; her assistant is no longer with her. The cloud formation appears and disappears, as impermanent, ethereal and lonely as fame itself.

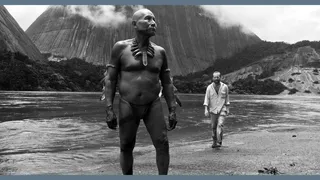

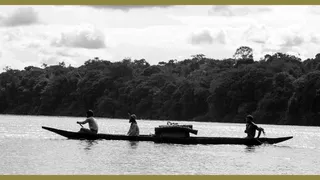

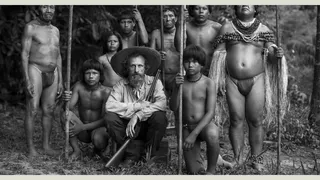

Embrace of the Serpent, dir. Ciro Guerra, 2015

8. Embrace of the Serpent, dir. Ciro Guerra, 2015

Colombian director Ciro Guerra chose to shoot most of Embrace of the Serpent in black and white to situate the film in the past, using old daguerreotype photographs as reference. The film weaves together two tales of white colonial encroachment, set 30 years apart, as the quest for a rare healing plant is undertaken first by Theo, a German ethnographer, in 1909, followed by Evan, an American botanist, in 1940. Their journeys are based on the diaries of real explorers to the Colombian section of the Amazon rainforest. Rather than telling the stories through the eyes of the colonizers, however, both narratives are relayed through the perspective of their shared guide, an indigenous shaman named Karamakate. This wise man (played by the younger Nilbio Torres and the older Antonio Bolívar) is an isolated surviving member of the Cohiuano tribe massacred during the rubber boom in the late 1800s. In the decades between the two journeys, it becomes tragically clear that Karamakate has lost much of his indigenous knowledge and heritage.

For Theo, the search for the healing plant yakruna is essential to treat his life-threatening illness. Karamakate has told him that only yakruna can save him, but that they must respect the jungle as they travel by boat and on foot to find it. “The jungle is fragile, and if you attack her, she retaliates.” Respect for the harsh environment of the Amazon rainforest was also taken into consideration by the director and crew, which meant working closely with the indigenous tribes to keep their impact on the location as minute as possible. Guerra invited the local tribes to work both in front of the camera and behind. Filming so remotely could mean that even a change of battery might need a river journey of several days. Multiple tribal languages are spoken in the film, and members of tribes were involved in the rewriting of the script. The people, who have lived in this region for more than 10,000 years, even performed rituals for spiritual protection during the seven weeks of production. Guerra credits these daily tribal rituals with a trouble-free shoot. The final film was screened in a converted maloca, an Amazonian longhouse. Some tribespeople traveled for three days for the screening. Guerro has said that it was “one of the most emotional screenings I have ever attended.”

The transfer and loss of knowledge is at the very heart of the film. The two men are on a tortured quest for botanical documentation in the spirit of the scientific age. They also serve to record the disappearing world of Karamakate as he struggles to retain his identity. The film meanders like a river between the two journeys, taking the viewer on a mythical fever dream that explodes into color in the last scene as Karamakate finally leads Evan to a strange lunar hillscape where he is able to sample the rare yakruna plant. At the request of the indigenous community involved in the filmmaking, the name “yakruna” is fictional. The real botanical name has been kept a secret to protect it from modern-day colonizers.

Evil Does Not Exist, dir. Ryûsuke Hamaguchi, 2023

9. Evil Does Not Exist, dir. Ryûsuke Hamaguchi, 2023

The small, unremarkable fictional village of Mizubiki, in the countryside hours away from Tokyo, serves as the setting for this enigmatic meditation on the relationship between community and the natural environment. Director Ryûsuke Hamaguchi chose a cast of nonprofessional actors, which lends a deadpan and understated sensibility to the film. The village is surrounded by dense woods and fields. Crystal-clear water from a stream of melted snow is gathered by Takumi—a local odd-job man and widower (Hitoshi Omika) with a young daughter named Hana (Ryô Nishikawa)—to be used for the village’s udon restaurant, which prides itself on the purity of its natural ingredients (wild wasabi is also harvested for a noodle dish). The peaceful mundanity of the villagers’ existence is suddenly threatened by a proposal from Playmode, a Tokyo-based talent agency, which plans to build a glamping site in the adjoining forest. Playmode is represented by the hapless Takahashi (Ryûji Kosaka) and Mayzumi (Ayaka Shibutani), who make the car journey to the town to try to gain the trust of the villagers. The proposal draws the ire of the community, which fears that its water will be polluted by the inevitable human waste from so many visitors staying upstream. The glamping site would also displace the deer that pass the village on their way to their watering hole.

Hamaguchi began work on the film at the suggestion of the composer Eiko Ishibashi (they had previously collaborated on the 2021 film Drive My Car). Ishibashi invited the director to her studio in the countryside to make visuals to accompany one of her music works. While there, he noticed how much nature affected her process and started exploring the area on his own (the resultant film is based on a real incident). In Evil Does Not Exist, the camera often lingers on trees, the woods, water, a bird of prey, creating a visual language that assumes the point of view of nature. This also gives it a sinister edge, capturing the violent elements—a dead deer, a gashed hand bleeding from a thorn.

From the start, the young Hana is seen exploring nature, walking through the woods, naming trees and plants. She is warned not to walk there alone, but this warning goes unheeded. At the end of the film, as darkness falls, Hana is nowhere to be found. A voice is heard sounding the alarm from the village loudspeaker. A search party spreads out into the forest. Takumi is joined by Takahashi, the city intruder, in the search, and they find Hana in a misty field near the edge of the forest. She is seemingly transfixed by a female deer and her gunshot-wounded calf. In part of the shocking and enigmatic ending, as Takahashi starts to approach the girl, Takumi wrestles him to the ground, locking him in a stranglehold. It’s hard not to read this explosion of violence as a punishment for the disrespect of the natural environment that Takumi holds so dear.

Sasquatch Sunset, dirs. Nathan Zellner and David Zellner, 2024

10. Sasquatch Sunset, dirs. Nathan Zellner and David Zellner, 2024

Boasting a stellar cast, including the nearly unrecognizable Riley Keough and Jesse Eisenberg, this wild comedy charts the survival instincts of a small family of mythical Sasquatch over the course of a year in the wilds of Northern California. The Sasquatch are played by human actors dressed in shaggy prosthetic costumes, grunting and banging logs to communicate. I heard many mixed reactions to this film but found it to be hilarious and surprisingly moving.

The director duo, brothers Nathan and David Zellner, specifically chose to emulate nature documentaries. The camera is most often set at an observational distance, as if the viewer is meant to study the primates from a removed, anthropological POV. Unlike many nature documentaries, however, there is no David Attenborough–style voiceover. We learn to interpret the grunts and gestures of the ape-like creatures, slowly adapting to their individual characteristics in the group dynamic as the Sasquatch make their annual migration through untouched old-growth forest. Communication of a sort mainly occurs during encounters with other animals. These comedic interactions feature a turtle, a badger, a skunk, a snake, and a mountain lion, all seemingly unimpressed with the shaggy Sasquatch.

As the film progresses, Homo sapiens intrude on this warped idyll. We sense that the group, possibly the last of their kind, is on a collision course with the humans responsible for the destruction of their habitat. The Sasquatch are disturbed by huge trees branded with painted red Xs that loggers have tagged, sealing their fate. They also chance upon an uninhabited encampment consisting of a small tent and cooking equipment, and explore the man-made items that have been brought into this natural environment. The female Sasquatch works out how to activate a boombox, which starts playing “Love to Hate You” by Erasure so loudly that it echoes through the forest. This enrages the remaining group to the point that they violently destroy the camp. Perhaps it was coming upon a newly paved road earlier in their trek that triggered them. Two of the Sasquatch defecate on this human-made intrusion in protest. It could be considered a measure of the success of this absurdist film that the road snaking its way through wild pristine nature made me feel nearly as angry.